Before the first railroad line reached San Antonio in 1877, the villa was known as “the city of adobes,” according to an 1887 article in the San Antonio Daily Express. Along with rock, adobe was cited as the most common construction material. Another report in the Express noted that local adobe buildings would “endure forever almost.”

“Forever almost” hints at the city’s adobe landscape today. Only a few historic homes constructed of adobe bricks—made from sun-dried mud and straw—survive. One of the city’s best-preserved examples is the Yturri-Edmunds Historic Site, which offers public tours that transport visitors to 19th-century life among the adobes.

Yturri-Edmunds Historic Site

128 Mission Road, San Antonio

Guided tours are given by appointment on Fridays for $10.

210-224-6163

saconservation.org

Architectural historians believe the home was built around 1859, said Vincent Michael, executive director of the San Antonio Conservation Society, which owns the site. The land used to be part of a farm operated by nearby Mission Concepción. “I never get tired of coming here,” Michael said during a recent tour. “It’s a rare chance to see frontier life in San Antonio.” The Yturri-Edmunds Historic Site also includes a reconstructed mill, an 1881 carriage house moved from San Antonio’s historic King William neighborhood, a one-room 1855 house relocated from the downtown area, and two remaining cabins built in the 1920s as part of Camp Roosevelt, a nearby tourist court that is now a public park. (The carriage house and cabins are not included in the tours.)

“I never get tired of coming here. It’s a rare chance to see frontier life in San Antonio.”

A limestone-lined dry channel from the mission’s ancient irrigation system, the acequia, brought water to the home as early as 1731. The land became available when Spanish authorities began to secularize Concepción and other missions in the 1790s. Then after Mexico won its independence from Spain, Manuel Yturri de Castillo obtained acreage through grants in the 1820s. Born in Spain’s Asturian Province, he immigrated to Mexico then moved to San Antonio to represent a mercantile business. In 1821, Yturri married Maria Josefa Rodriguez, a descendant of the original Canary Islands families sent to populate San Antonio by authorities of Nueva España in 1731.

Michael pointed out a framed family tree in the adobe home, which states the islanders arrived in San Antonio on March 9, 1731, at 11 a.m. “That’s pretty good timing for a group walking hundreds of miles from Vera Cruz,” he joked.

The music room in the Yturri-Edmunds home where Ernestine Edmunds lived until her death in 1961.

Photo: Will van Overbeek

Construction of the house began sometime after the Yturris died-—Manuel in 1843, Maria in 1849. Their daughter Vicenta and her husband, Ernest Edmunds, took possession of the home before their 1861 wedding at Mission Concepción.

Originally, the home included only two rooms, represented today by the music room and parlor.

An unplastered section of the 18-inch-thick wall on the home’s front porch provides a look at the adobe bricks. The exact formula for such bricks varies greatly, and the Yturri-Edmunds Home builders are said to have mixed goat’s milk and goat’s hair with earth for its bricks.

Originally, the home included only two rooms, represented today by the music room and parlor. A bedroom was likely added in the 1860s to the house’s main wing, then three smaller rooms—a kitchen, dining room, and school room—were at some point built onto the back of the structure.

Ernest Edmunds died in 1874, the same year the couple’s youngest of three children, Ernestine, was born. To support her family, mother Vicenta taught school, a profession notably followed by Ernestine. Miss Edmunds, as Ernestine was often called, lived in the home until her own death in 1961, upon which she bequeathed the site to the San Antonio Conservation Society. About a quarter of the home’s furnishings are items owned and used by the family, and the rest are period pieces representing the late 19th century.

Ernestine played guitar and piano, and the music room features both a parlor organ and her own piano with its distinctive bench with a back. There’s also a family rocking chair and a cabinet of toys, curios, and souvenirs, many of which were given to her by appreciative students.

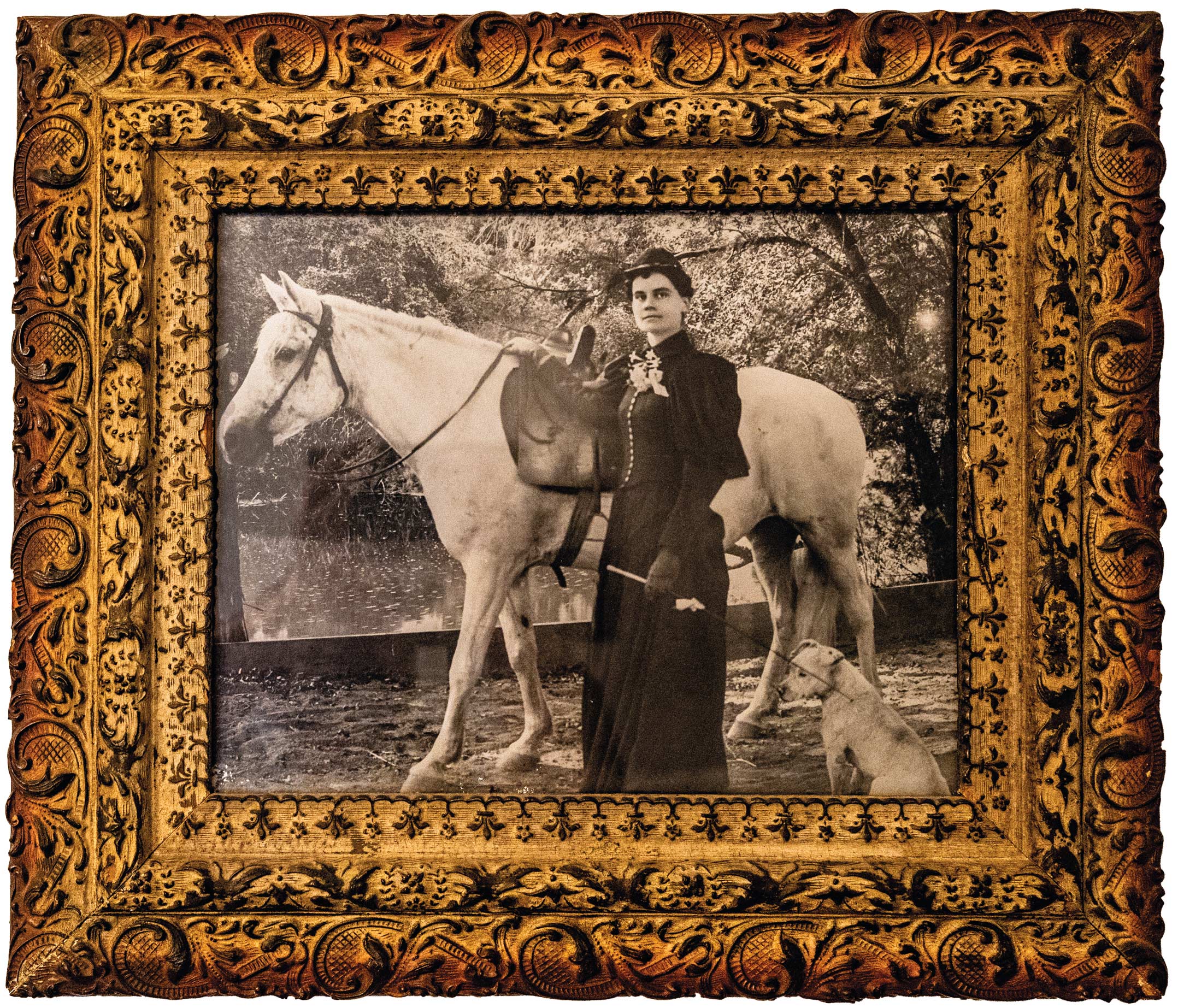

Ernestine Edmunds

Something of a Renaissance woman, Ernestine was also an accomplished painter, and the parlor exhibits her work. In one painting, her parents stand outside Mission Concepción on their wedding day in 1861. Another, replicated on the nearby stretch of the San Antonio River Walk, depicts the mill as it once stood beside the family home. A note written by Ernestine—a devout Roman Catholic with mystical inclinations—and found on the back of an antique clock in the parlor stated that the clock stopped at the exact moment her mother Vicenta died.

In the bedroom, Michael noted that schoolkids who tour the home are amazed by the chamber pot and wash basin. And the primitive hair curlers that were heated in the oil lamp give kids the heebie jeebies. “The kitchen had been modernized, so we had to bring it back to period,” he added, pointing out the vintage stove, irons, candle molds, and pie cabinets with ant traps on the legs.

A photo of Ernestine on the wall of the dining room, which is the only room in the house without an outside door, shows her standing beside her horse, Gunpowder, whom she rode 23 miles each day to teach in Alamo Heights. The study room, where both Vicenta and her daughter tutored children, includes some of Ernestine’s original books.

A small grotto honoring the Virgin Mary behind the home was placed by Ernestine after Vicenta experienced several visions of a lady in white.

The only extant original features of the reconstructed mill are an adobe wall and stone foundation. The current mill is powered by electricity, not water, and tour guides demonstrate the method of grinding grain into flour for school groups.

“In addition to showcasing a rare historic example of adobe construction,” Michael said, “we hope visitors get a vivid sense of life in the last half of the 19th century. The kids can’t believe it till they see it—and sometimes not even then.”