Derricks filled the town of Ranger during the oil boom, as depicted in this circa-1920 photo on display in the Roaring Ranger Oil Boom Museum. Photo: Courtesy Roaring Ranger Oil Boom Museum

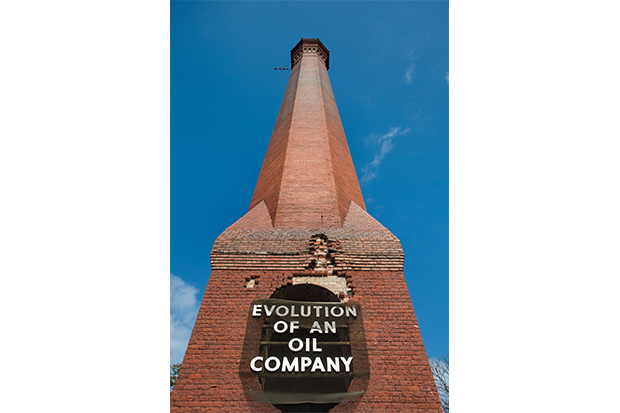

Driving east on Interstate 20, I crest an incline in the rolling landscape between Abilene and Fort Worth. In the valley below, a brick smokestack cuts a dramatic profile against the surrounding hills. The tower rises from the horizon like a sentinel, watching over the site where the bustling town of Thurber stood at the turn of the 20th century.

In those days, the electric plant’s 148-foot-tall smokestack loomed over wood-frame houses and grand Craftsman homes, a mercantile and opera house, churches and schools. Now, nothing of Thurber

In the early 20th century, the 148-foot-tall smokestack loomed over wood-frame houses and grand Craftsman homes, a mercantile and an opera house, churches and schools.

When I’ve almost reached the smokestack, I exit the interstate and drive a couple of blocks to the W.K. Gordon Center for Industrial History of Texas, where I’ve come to learn why Thurber disappeared. The Gordon Center, a branch of Tarleton State University, is my first stop on a trip that includes the Roaring Ranger Oil Boom Museum in nearby Ranger and the Swenson Memorial Museum in Breckenridge. Together, the three museums (in Erath, Eastland, and Stephens counties, respectively) chronicle the region’s booms and busts in the early 20th century, a Texas tale that echoes throughout the state to this day.

Thurber

With the advent of mining here in the late 1880s, Thurber developed as one of the state’s most prominent coal towns, providing coal to power trains on the Texas and Pacific Railroad. In 1897, a second industry developed in Thurber when the Texas and Pacific Coal Company began using shale from the nearby hills to make bricks. Some of those bricks were used to pave Austin’s Congress Avenue and Fort Worth’s Camp Bowie Boulevard, where they’re still visible today.

The Thurber smokestack. Photo Michael Amador

Inside the museum, I take a seat inside a replica of the Thurber opera house to watch a short film about the town’s history. The film explains how Texas and Pacific Coal built an entire town to serve the mines. At its peak Thurber was home to 10,000 people, an ethnically diverse group of mining families that together comprised the largest city between Fort Worth and El Paso. The company owned the houses, stores, schools, and saloons. Residents didn’t pay city or school taxes, but the miners worked in dangerous conditions and were subject to the whims of the company officials who ran the town.

After the movie, I wander among the museum’s replicas of old Thurber buildings, including a bandstand and livery stable. When I step inside the drug store, I’m greeted by the voice of an unseen “proprietor:” “Hello! Welcome to Thurber’s only drug store, the center of all social activity. We carry an outstanding line of pharmaceuticals and potions as well as toys and fancy goods.”

In the Thurber mines, the men crawled into small tunnels and lay on their sides, propped on one arm, to dig the coal. A life-size diorama, complete with the repetitive sound of the pick prying coal from the wall, shows a man working in this uncomfortable position. I crouch to view the scene from a miner’s perspective and am overcome with both claustrophobia and gratitude that I work above ground.

The W.K. Gordon Center for Industrial History of Texas. Photo: Michael Amador

With the 1901 discovery of oil at Spindletop in Beaumont, prospectors ramped up their search for oil in other parts of Texas. W.K. Gordon, the superintendent of the Thurber mines, was among them. He had another motivation to drill: The Allies’ need for oil during World War I had created a domestic oil shortage even before the United States entered the conflict.

“Indirectly, the oil booms were because of war,” explains Shae Adams, the Gordon Center’s curator of exhibits and education. “People knew that if they found oil, they could sell it to the government.”

In October 1917, Gordon struck oil near Ranger, 16 miles west of Thurber. At the Gordon Center, a replica of an oil derrick re-creates the drama. Visitors can push a button to hear the rumble in the earth and see a simulated oil gusher. Ironically, Gordon’s success indirectly led to Thurber’s demise. Railroads began to power trains with oil instead of coal, and roads were paved with petroleum-based asphalt rather than brick. Texas and Pacific closed the Thurber coal mines in 1926 and the brick plant in 1931. It sold the houses and salvaged materials from other buildings. By the late

Ranger

As Thurber’s fortunes busted, Ranger’s boomed. The Roaring Ranger Oil Boom Museum illustrates the transition with a collection of black-and-white photos, newspaper articles, and 1920s souvenir publications. The museum building—the 1919 red-brick Ranger railroad depot—still has the vintage ticket windows and clock, making it easy to imagine waiting for the next train to arrive from Fort Worth. During the height of the boom, from 1917 to 1921, the depot saw 1,500 people pass through its doors every day.

The Roaring Ranger Oil Boom Museum. Photo: Michael Amador

In towns like Ranger and Breckenridge, the boom lasted only a few years until the wells’ production began to decline.

Ranger’s population swelled from several hundred to 30,000 during the boom, and by 1920 more than 800 wells pumped oil from underneath the town. A panoramic photo depicts this otherworldly scene—a town teeming with derricks that rise from the landscape like a futuristic forest. But there was one place speculators couldn’t drill. While the Merriman Baptist Church earned $200,000 a year from allowing wells in its churchyard, it refused a $1 million offer for an oil lease in its cemetery. A framed photo shows the graveyard, flanked by two giant derricks, with a sign posted on the fence: “Respect the dead.”

By 1921 Ranger had paved the streets of its business district, constructed new schools, and rebuilt after a 1919 fire destroyed several blocks of downtown buildings. A booklet published by the West Texas Chamber of Commerce in 1921 explains: “The big permanent building period began immediately after the fire, and a transformation, almost as if by magic, has taken place in a little less than two years. … Complete systems of waterworks, sewers, natural gas, and electric lights were installed and the city was soon given all the conveniences of older municipalities.”

Breckenridge

Prospectors found oil in Breckenridge, a half-hour’s drive northwest of Ranger, a year after Gordon struck oil. Breckenridge was the county seat of this ranching area, and the boom drove the population up from 1,500 to about 30,000 as oil derricks popped up across town. The boom days were well documented by Basil Clemons, an eccentric photographer

A 1925 oilfield truck in the Swenson Memorial Museum’s oil annex. Photo: Michael Amador

“We wouldn’t know the history of Breckenridge and Stephens County if it wasn’t for him,” says Kay Meadows, a staff member who shows me the collection of Clemons photos at the Swenson Memorial Museum. “He went to all the oilfield fires, and he took pictures of everything: the school, the circus, the Rotary club, the football boys, you name it.”

I page through the binder of Clemons’ photos, all snapshots of Breckenridge in the 1920s. His images preserve scenes like the high school’s junior-senior banquet; a 1926 rally for gubernatorial candidate Dan Moody; and the billowing smoke of oilfield fires. Clemons captioned one apocalyptic scene: “Our Fire Chief—Heaven Bless Him For Doing The Best He Can With What He Has To Do With.”

In the J.D. Sandefer Oil Annex of the Swenson Memorial Museum, photos by Clemons and others illustrate the mixed blessing of the boom. (Closed for construction, the annex is scheduled to reopen this spring.) One picture shows the tents, shacks, and boardinghouses cobbled together to house oil workers. Another depicts the courthouse, built partly to handle the exponential increase in crimes like bootlegging, prostitution, and assault.

Swenson museum in Breckenridge. Photo: Michael Amador

Yet amid the rowdiness, oil brought Breckenridge better schools, a municipal water system, paved streets, and access to the railroads. It allowed the First National Bank to build, in 1920, the three-story cream-colored Beaux Arts building that today houses the Swenson Memorial Museum.

In towns like Ranger and Breckenridge, the boom lasted only a few years until the wells’ production began to decline. “In Ranger, they were still finding oil, but the amount dropped so dramatically that it wasn’t as profitable,” Adams explains. “Companies couldn’t hire as many people because oil wasn’t coming in at the same rate as the first two or three years.” The transient workforce took off when higher-paying jobs popped up elsewhere. By the 1930s Ranger’s population dropped to roughly 6,000, a fifth of what it had been a few years earlier.

As I drive home from Breckenridge, I find it hard not to consider comparisons with the oil and gas booms shaping towns in Texas today. The discovery of an energy source can pad a town’s pockets while simultaneously straining its infrastructure. But before long, the crowds move on, seeking their fortune in the next big boomtown—a timeless cycle well preserved in Thurber, Ranger, and Breckenridge.

Visit the Boomtown Museums

1. W.K. Gordon Center for Industrial History of Texas

65258 I-20 in Mingus

Open Tue-Sat 10 a.m.- 4 p.m. and Sun 1-4 p.m.

Admission is $5 for adults and $2.50 for children ages 5-12.

Call 254-968-1886

tarleton.edu/gordoncenter

2. Roaring Ranger Oil Boom Museum

121 S. Commerce in Ranger

Open by appointment

Admission by donation

Call the Ranger Chamber of Commerce at 254-647-3091.

3. Swenson Memorial Museum

116 W. Walker St. in Breckenridge

Open Tue-Fri 10 a.m.-5 p.m. and Sat 10 a.m.-2 p.m.

Free admission

Call 254-559-8471.