In the days following the Columbia space shuttle’s disintegration over East Texas 20 years ago, the Piney Woods of Sabine County became hallowed ground. As part of the recovery team seeking the Columbia’s remains in the wilderness, local Baptist pastor and volunteer firefighter Fred Raney found himself leading impromptu memorial services, what he calls “chapels in the forest.”

Around 9 a.m. on Feb. 1, 2003, as thousands of pieces of the STS-107 shuttle thundered down, Raney and many Hemphill locals were suddenly thrust into critical new roles. Raney became an outdoor chaplain for the search team, composed of thousands of local volunteers and members of the National Guard, Texas and U.S. forestry services, NASA, the FBI, and other groups. Together, they put on boots, rain slickers, and hard hats, and trudged through the brambles to search for the remains of the seven astronauts aboard the shuttle.

“Remembering Columbia”

Museum

375 Sabine St.

Unit B, Hemphill.

Open Tue-Sat.

$5 adults; $3 students.

409-787-4827;

nasacolumbiamuseum.com

“When we found the astronauts, everyone just stopped in silence,” Raney says. “I knew Columbia’s Commander [Rick] Husband had read Joshua 1:9 to his astronauts, so I read that scripture and said a prayer. Afterward, there was not a word said—it was very respectful. We walked through the thick woods silently, like a funeral procession, and made the trip back to the vehicle that would carry the astronauts’ remains to town. It’s something I’ll remember to the day I die.”

Of the many stories contained within the Columbia tragedy, the goodness and perseverance of the residents of Hemphill is one of the most enduring. According to Bringing Columbia Home, an engrossing book published in 2018 about the Columbia’s final voyage, the ground search and recovery operation was the largest in U.S. history. The town swelled from a population of 1,100 people to over 10,000 during the two months of recovery. And much of its success is owed to the citizens of Hemphill.

Within hours of the first shuttle pieces falling, Belinda Gay, then president of the Ladies Auxiliary of the Veterans of Foreign Wars in Hemphill, turned the VFW Hall into recovery headquarters. Grabbing naps on a cot in the VFW office, she organized what became known as “the great feed.” Hemphill residents woke as early as 2 a.m. to serve three hot meals a day to the thousands of newcomers to their town. Families welcomed strangers into their homes, seeding friendships that continue to this day. The National Guard moved into the high school gym, town electricians set up extra phone lines for the FBI and NASA, and the town funeral director performed funereal duties free of charge. Adrenaline, camaraderie, and many cathartic tears sustained volunteers through weeks of little sleep.

“You know, our community is a very humble place,” says Gay, who, along with Marsha Cooper of the Texas Forestry Service, heads the Columbia Memorial Committee. “We’re just a bunch of country folks, and we just want to do what’s right. We had to do our part and try to recover the Columbia and take care of all those people who came here to our community. It’s hard to explain.”

Gay, Cooper, and other local leaders who assisted the Columbia recovery have ensured the astronauts’ legacies live on. In 2005, their committee installed the Columbia Star at the intersection of State Highway 87 and Farm-to-Market Road 83. The circular concrete platform is 20 feet in diameter and painted red, white, and blue with a star and the Columbia mission insignia. Words encircling it read “Their Mission Became Our Mission.” The star is flanked by a historical marker engraved with the astronauts’ names. There is also a monument to two searchers: pilot Jules “Buzz” Mier Jr. and Texas Forestry Service aviation specialist Charles Krenek. Both died in a helicopter crash during recovery.

In 2009, the committee opened the Patricia Huffman Smith NASA “Remembering Columbia” Museum, funded by real estate developer Albert Smith and named in memory of his late wife. Housed in a nondescript beige metal building, the museum conveys the significance of the Columbia disaster and memorializes the astronauts. A group selfie on display—taken during the mission by Husband, a U.S. Air Force colonel and native of Amarillo—is particularly striking. In it, all of the astronauts float together in a zero-gravity huddle, smiles on their bright faces. The photo was retrieved from a camera found in the wreckage.

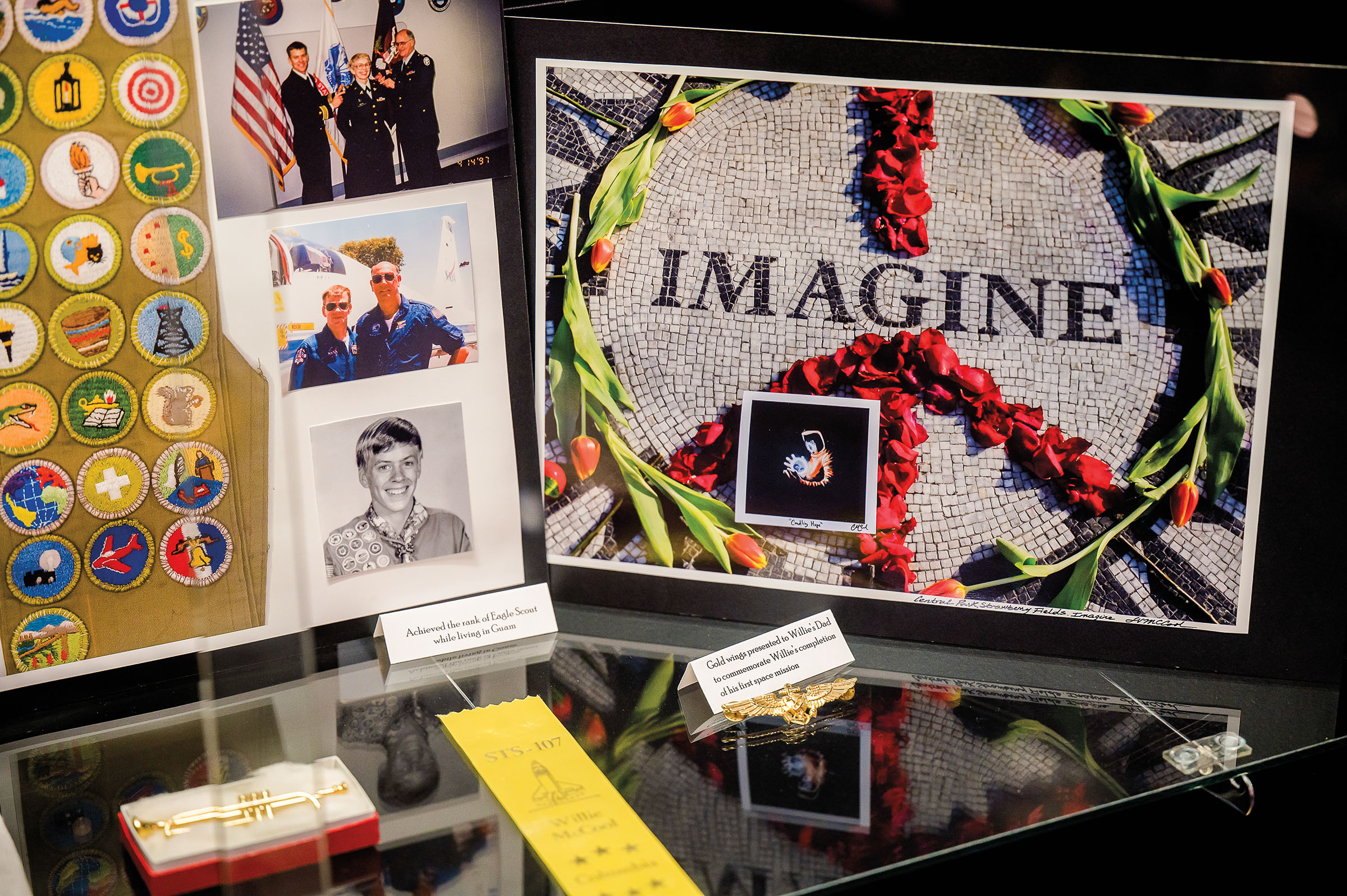

The museum features a 7-foot glass case dedicated to each astronaut. One case contains the running shoes of Lubbock native Willie McCool, the boyishly handsome Columbia pilot who was a dedicated runner. McCool’s case also includes a photo of John Lennon’s memorial in Central Park. “Imagine” was McCool’s favorite song, and ground control regularly played it for the crew while on board the shuttle. These personal artifacts allow visitors to zoom out from the tragedy and see the bigger picture of the astronauts’ lives.

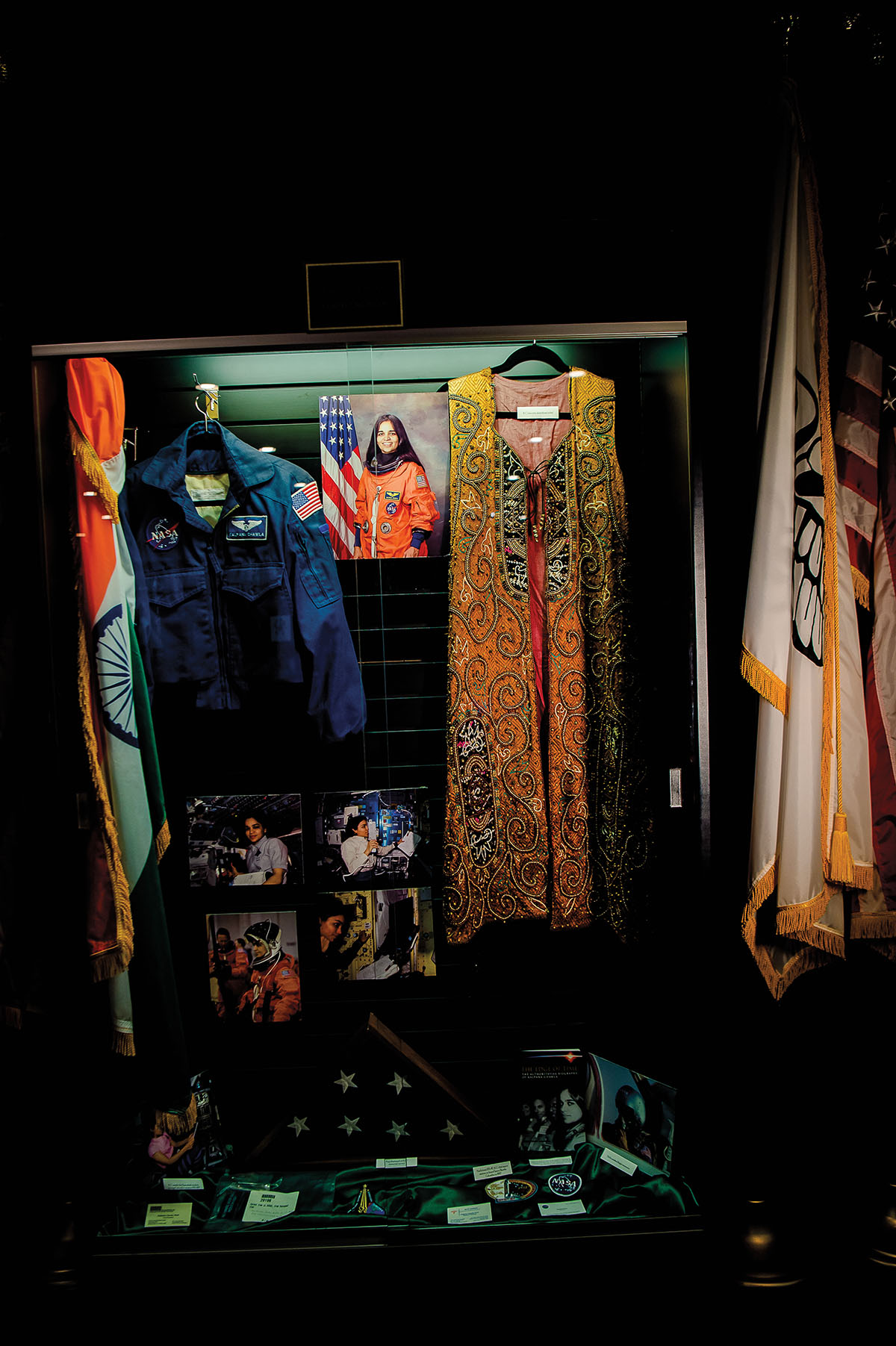

A beaded dress stands out among the personal belongings. It was a favorite of astronaut Kalpana Chawla, a native of India who moved to Texas in 1982 to attend the University of Texas at Arlington, where she received a master’s degree in aerospace engineering. “That dress was hard to part with, but it doesn’t do any good in my basement,” says Jean-Pierre Harrison, Chawla’s husband of close to 20 years at the time of the Columbia disaster. “In public, Kalpana was always wearing the blue NASA jacket or orange pressure suit, so that dress shows another side of her personality. I’m happy for the museum to have it. I felt like we were in this together.”

Harrison has found his own way to preserve the legacy of the astronauts. He wrote a biography of Chawla, The Edge of Time, and corresponds with girls from India who look up to Chawla as a role model. He has offered guidance to one Indian woman studying to be an astronaut and recently selected an Indian filmmaker to lead the production of a biopic about Chawla.

Hemphill’s memorial committee also seeks to inspire students in science and engineering. As part of a three-day anniversary event this year, the town will host a robotics competition for local high school students, with NASA representatives in attendance.

“How many kids in this East Texas area are going to have that opportunity?” Gay asks. “If you live in Houston, maybe. But if you live in small rural towns, your chances of working with an astronaut or engineer aren’t very high. Through this, we’re keeping the astronauts’ legacy alive.”

Raney’s chapels in the forest ended 20 years ago, but Hemphill will always remember. For many, the Piney Woods of Sabine County remain sacred ground.

Columbia Remembered

A 20th-anniversary memorial event will take place Jan. 30-Feb. 1 in Hemphill. Speakers from NASA, Boeing, and other organizations will present at the “Remembering Columbia” Museum.

There will be an art show, a robotics competition, and panel discussions. An anniversary program, “STS-107 Still Our Mission: 20 Years Later,” will take place at the First Baptist Church on Feb. 1 at 7:45 a.m. For more information, visit nasacolumbiamuseum.com.