It was the O.J. Simpson trial of its day. Reporters descended on the northeast Texas town of Jefferson to chronicle the tragic tale of Diamond Bessie with black ink and purple prose. Nobody recognized the dashing young couple Annie Moore and Abe Rothschild when they checked into a local hotel in January 1877. But when Moore’s body was found in the woods two weeks later, a bullet in her head, the mystery of Moore, aka Diamond Bessie, catapulted Jefferson into the national spotlight.

The Jefferson Playhouse

1860 N. Market St.

The Jefferson Playhouse hosts the 65th annual Diamond Bessie Murder Trial on May 2-3, 7:30 p.m.; May 4, 5:30 and 8:30 p.m.; and May 5, 2 p.m.Tickets cost $20.

903-665-0737

jeffersonpilgrimage.com

The tale unfolded in dramatic fashion: Rothschild, the miscreant son of a prosperous Cincinnati jewelry family, had married Moore, forced her into prostitution up and down the Mississippi River, and beaten her when she didn’t earn enough money. Arriving in Jefferson under an alias, the couple’s glamorous fashion turned heads and sparked Moore’s “Diamond Bessie” nickname. But what exactly happened that Sunday afternoon, when the two were last seen walking across the bayou bridge going south from town?

That would be a matter for the law to decide, and in Jefferson, the trial is still unfolding to this day during the annual Jefferson Historical Pilgrimage. Each May for the past 65 years, Jefferson rewinds the calendar to the 19th century and replays the Diamond Bessie murder mystery, exploring a tale that captivated the town during its waning days as a prominent inland river port.

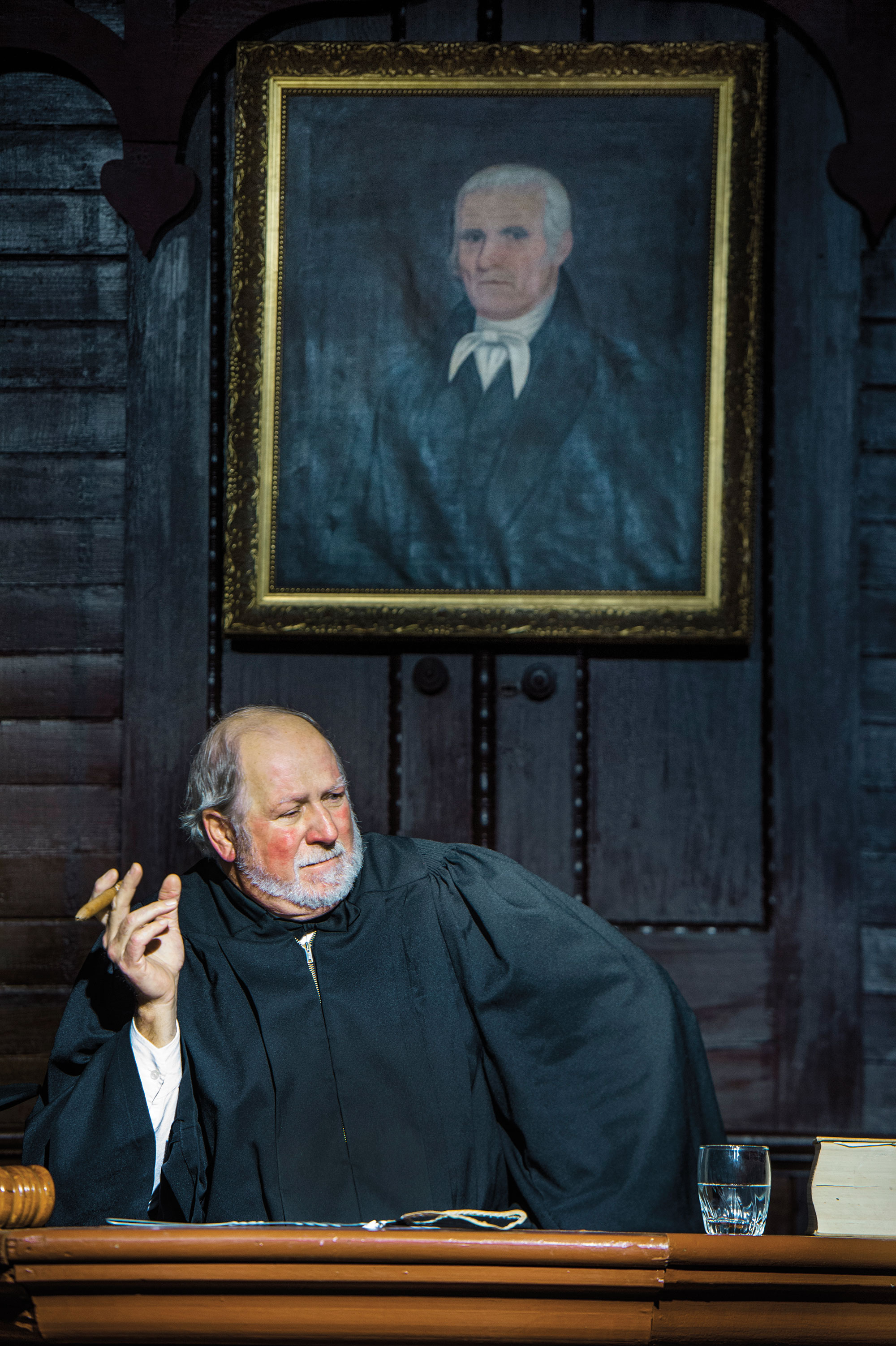

When court convenes in a stately building near downtown, the year could be 1877—or 2019. Tension electrifies the air as excited spectators pack the gallery, and opposing lawyers make last-minute preparations. At the booming command of a burly sheriff, 12 jurors march in, many wearing felt hats and string ties. The sheriff warns them against spitting in the courtroom. The judge chomps a cigar and slams his gavel down for proceedings to begin.

Jefferson resident Lawton Riley wrote the Diamond Bessie Murder Trial in 1955 using manuscripts of the actual trial, and the Jessie Allen Wise Garden Club has staged the volunteer production ever since. For the last 11 years, the Garden Club’s Bobbie Hardy has directed performances.

“It’s one of those jobs you get because you are interested and dedicated to the cause,” she says. Cause is the right word, given the devotion of those involved. “People get into this play, and dying is about the only way you lose your role.”

The late Bill Cornelius, a judge in real life, wrapped up a 50-year run as the play’s defense attorney in 2012. Two years later, Becky Palmer stepped down after 30 years as Diamond Bessie’s ghost. And relative newcomer Mitchel Whitington, an author and historian who has played Sheriff John Vines since 2009, got so caught up in what he calls the “wonderfully tragic tale,” that he wrote a book (Diamonds and Death, 2015) about the crime and the folklore that has grown around it.

When the real Diamond Bessie arrived in Jefferson with Rothschild on Jan. 19, 1877, Whitington recounts, locals were dazzled by her looks—silk stockings, diamond rings, and a velvet hat. The couple was spotted walking across the Big Cypress Bayou bridge two days later. Rothschild reappeared in town alone and soon left by train. It wasn’t until Feb. 5 that a woman collecting firewood found Bessie’s body lying in the snow, shot through the temple, in the same woods she and Rothschild had walked into two weeks earlier.

“It’s one of those jobs you get because you are interested and dedicated to the cause. People get into this play, and dying is about the only way you lose your role.”

Though Diamond Bessie was a stranger in town, the killing touched local hearts and fired a thirst for justice. Jefferson’s economy and population had been declining since 1873, the year the government removed a massive logjam from the Red River, which dropped water levels on Big Cypress Bayou and diminished Jefferson’s viability as a river port. Nonetheless the town decided to pay for Diamond Bessie to have a proper burial in the local cemetery. Authorities also traced Rothschild to Cincinnati, where he had shot his own eye out in what appeared to be a failed suicide attempt. Sheriff Vines brought him back to Jefferson for trial. Alongside him was the best team of lawyers his family’s money could buy. The events went viral, 19th-century style. “Every state, the far corners of the country were talking about Diamond Bessie,” Whitington says.

After 142 years, the rest of the world has forgotten about Diamond Bessie. But in Jefferson the re-enactment keeps the episode alive with five performances during Pilgrimage. Don’t expect a Broadway-style production or a scrupulous rendering of history, though. Over the years, the show has taken on comedic elements. And while there are some serious performers involved, including in 2018 Mickey Kuhn, who played young Beau Wilkes in 1939’s Gone with the Wind, most of the cast members are regular folks having fun. Ad libs and sly jokes come as fast as shots from a Colt .45.

Jefferson Pilgrimage also includes Civil War camp and battle re-enactments.

Photo: Michael Amador

But near the end of the show, when the foreman of the jury stands, silence falls. Any lingering humor dissipates from the room as he announces the verdict: not guilty. After all the years, it still surprises, still feels unsatisfying. From a literary standpoint, it helps that the ghost of Diamond Bessie appears and has her say to Rothschild, reminding him of his own mortality.

“You’ll come to me,” she says. “And over here, there is but one trial—and no defense.”

Was Rothschild really haunted by Bessie’s memory, as the play implies? Was it poetic justice that, after more run-ins with the law across the country, he was disinherited from his family’s wealth? The truth of the murder, of course, is known only to people who are now gone. For the rest of us, it remains as murky as the surface of Big Cypress Bayou, where centuries-old bald cypress trees crook their knees and keep silent watch.

A Pilgrimage to the Past

Jefferson festival offers home tours and history

Diamond Bessie’s murder trial is not the only time-warp activity you’ll find during the annual Jefferson Historical Pilgrimage. Driving into town you may even think you’ve entered The Twilight Zone as re-enactors interpret Jefferson’s history as an antebellum inland river port on Big Cypress Bayou.

Civil War soldiers make camp and drill beside the road. Ladies in colorful hooped skirts seem to float in front of 19th-century homes. You might even meet a pair of women displaying quilts and singing African American spirituals. Their songs and quilts together form a code directing slaves to the underground railroad—a trail to freedom in the North.

“Our aim with Pilgrimage is to keep our history alive and before the public,” says Mary Keasler, who has chaired the event for the past six years.

The Jessie Allen Wise Garden Club started a spring festival in 1940, and in 1950 the event was named Jefferson Historical Pilgrimage to reflect a broader focus. Today, activities include a homes tour, parade, handmade craft fair, and heirloom plant sale.

The weekend also features Civil War reenactments with a ground skirmish including a locomotive chase at Cypress Creek Ranch on Saturday and a naval clash on Big Cypress Bayou on Sunday.

The 2019 Jefferson Historical Pilgrimage will be May 2-5. For more information and to purchase tickets for the homes tour, visit jeffersonpilgrimage.com.