The Benson cabin is showing its age. Thought to be one of Galveston County’s oldest existing structures at over 170 years old, the dogtrot cabin’s wood is peeling off in places, and unruly green shrubbery is overtaking its base. Inside, a decrepit stovetop lies on the floor near a brick fireplace.

The cabin was built in 1844 by Herman Benson, a German immigrant who bought 484 acres along Dickinson Bayou, according to the Bay Area Genealogical Society Journal. Though the cabin, still on private land, has fallen into disrepair, members of the Emancipation Historic Trail Association hope to preserve the site as part of their effort to create the Emancipation National Historic Trail. The proposed 51-mile trail would honor the migration of freed slaves and other African Americans from Galveston to Houston after the Civil War.

Studying 19th-century maps to piece together a possible route, volunteers Brady Mora and Naomi Carrier noted places where the travelers may have stopped for water, including Benson’s well or cistern. “They were ordinary people doing extraordinary things,” Mora says. “They are unheard of, these Americans. The creation of the national historic trail is a just cause. It’s not for us; it’s for the generations that come after us. They need to know the truth.”

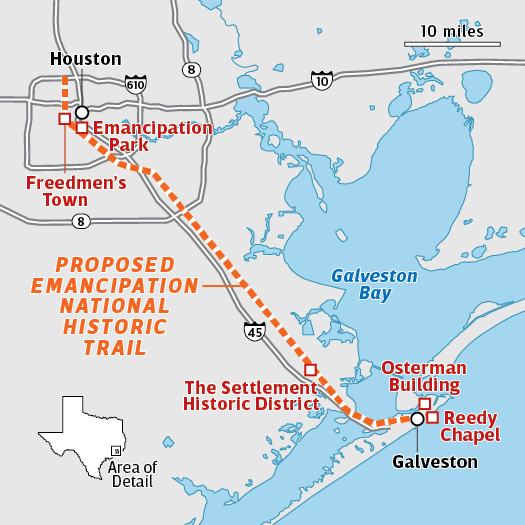

The proposed trail starts in Galveston at the Osterman Building and Reedy Chapel, where Major General Gordon Granger announced the federal order freeing slaves on June 19, 1865—a date now celebrated as Juneteenth. From Galveston, the trail extends to Houston’s Fourth Ward, where emancipated slaves settled during Reconstruction and built an enclave known as Freedmen’s Town. Advocates say the trail will bring to life the stories of enslaved people in Texas, many of whom didn’t learn of their freedom until Granger’s announcement, two years after President Abraham Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation.

It was a daunting trek for former slaves with few resources to make their way across Texas, which had been part of the Confederacy, in search of safety and opportunity after the Civil War. As the war ended, political, social, and economic turmoil roiled the state. Carrier, the founder and CEO of Texas Center for African American Living History, has studied Black history for decades, including slavery in Texas, which led her to look into the Emancipation Trail.

“My images are the faces of a Black family in a cotton field and the faces of a Black family today outside their two-story home,” she says. “A lot of activism had to take place. A lot of people died in order for the faces of African Americans to look like they look today.”

If the Emancipation Trail meets federal eligibility and is approved by Congress, it would be only the second national historic trail honoring African Americans. The Selma to Montgomery trail marks the route of the 1965 Voting Rights March that Martin Luther King Jr. led to the steps of the Alabama Capitol. The National Park Service’s 18 other historic trails cover such topics as the Lewis and Clark expedition and the Trail of Tears.

Texas is currently home to two national historic trails. The El Camino Real de los Tejas trail runs from the southwestern border to Natchitoches, Louisiana, and recalls Spanish colonization of Texas and northwest Louisiana. The El Camino Real de Tierra Adentro trail starts on the border in the El Paso area and runs to Santa Fe, New Mexico. It also covers the legacy of Spanish exploration, trade, and colonization.

In 2019, U.S. Sen. John Cornyn and U.S. Rep. Sheila Jackson Lee, both of Texas, introduced the Emancipation National Historic Trail Study Act, which started a Park Service feasibility study of the proposed trail and its historical significance. The study’s findings, expected by the end of 2023, will be shared with Congress, which could then designate it a national historic trail. That would allow for a management plan and marking historical sites as permitted by private landowners.

Map by Alan Kikuchi

In the last year, Carrier and Mora have worked to create a layout of the route freed slaves may have taken after leaving Galveston, which was a major seaport in the 1860s. They linked historical sites, creeks and bayous, and old settlements. In Galveston, the Osterman Building is gone, but a historical marker on Strand Street notes the site’s significance. The adjacent Absolute Equality mural on the Old Galveston Square building commemorates Juneteenth. Nearby, Reedy Chapel, the first African Methodist Episcopal Church in Texas, traces its congregation’s founding to 1848.

From Galveston, the trail travels across Dickinson Bayou at Benson’s cabin and then to Friendswood across Chigger Creek and Cowart Creek among others. In Texas City, the trail includes the Bell Home, a dogtrot cabin built by Frank and Flavilla Bell in 1887. Now a museum, the home is part of the 1867 Settlement Historic District, which was the only Reconstruction-era Black community in Galveston County.

As it winds its way into Houston, the trail includes stops at Freedmen’s Town, where starting in 1866, freed slaves formed their own community, building shanties as houses; and Independence Heights, in northwest Houston, which became the first African American municipality in Texas upon its 1915 incorporation. In Houston’s Third Ward, Emancipation Park dates to 1872, when Black community leaders raised $1,000 to buy 10 acres for a place to celebrate Juneteenth.

Carrier first got involved with the Emancipation Trail’s creation when she began to do research for Jackson Lee’s office. Carrier flew to Alabama, drove the Selma to Montgomery National Historic Trail, and met with people who worked on the trail. She said she was impressed by the museums along the route commemorating King’s march. She’d like to see something similar developed along the Emancipation Trail.

Jill Jensen, the National Park Service’s project manager for the Emancipation Trail feasibility study, says the study is looking for oral histories, written accounts, photographs, and other resources to try to verify when people traveled across the trail and how their movement impacted the nation—two

key requirements of a national historic trail designation.

Jensen sites the California Trail as a good example. “You had people physically moving along this path, going to the West, which completely changed the politics and dynamics of the entire country,” she says. “Selma to Montgomery is another really great example. It was the actual movement of their bodies along that path that triggered amazing nationwide change.”

Carrier, Mora, and others have been combing through slave narratives, as well as estate, church, land, cemetery, and military records to help paint a historical picture of the Emancipation Trail. But the lives of many freed slaves who made the journey remain a mystery. “That’s the problem with the freed men,” Mora says. “They had names, but we don’t know [their stories]. Some made it to Houston. Some didn’t make it.”

Public input is also key to the creation of a national historic trail. The Park Service hosted three virtual meetings earlier this year to gather information from people who live in the area of the trail or have stories of people migrating from Galveston to Houston. The Emancipation National Historic Trail Association also conducted an online survey about the feasibility study, yielding 115 comments and 25 letters of support.

“Most people said they had never heard of it,” Carrier says. “Most people also said they thought that it was needed because of the stories that it would tell. They thought it was relevant because it would stimulate the economy in areas where tourism is needed.”

Within the Freedmen’s Town National Historic District, the Rutherford B.H. Yates Museum preserves a three-bedroom 1912 home. The museum’s historical research director, Debra Blacklock-Sloan, has been studying historical records to identify African Americans who migrated to Houston from Galveston after emancipation. She’s also calling on others to bring their family stories forward to deepen the history of the Emancipation Trail.

Trail Markers

The National Park Service provides information about its Emancipation National Historic Trail feasibility study and opportunities for public comment on its website, parkplanning.nps.gov. Some sites on the proposed trail are open to the public and have exhibits exploring African American history.

Reedy Chapel, Galveston: Established in 1848 for slaves, this was the first African Methodist Episcopal Church in Texas. reedychapel.com

The Bell Home, Texas City: The dogtrot-style house is part of the 1867 Settlement Historic District, the only Reconstruction-era Black settlement in Galveston County. texascitytx.gov/459

Rutherford B.H. Yates Museum, Houston: Located within Freedmen’s Town National Historic District in the Fourth Ward, this house museum preserves the history of a Houston community formed by freed slaves starting in 1866. facebook.com/yatesmuseums

Emancipation Park, Houston: Founded in 1872 by Houston’s Black community to celebrate Juneteenth, the park now covers 10 acres in the Third Ward. epconservancy.org

“Sometimes we’re reluctant to talk about the past because it’s shameful, but it’s a healing process,” Blacklock-Sloan says. “Our ancestors were enslaved for so many centuries, and then they’re able to just say, ‘OK, I’m going to go ahead and make a life for myself and for my family, and I want to be part of the American way.’ They did this against all odds, against the outrages of white Southerners who didn’t want to see Black folks better themselves. It is important to have this trail, to educate, and to remember.”