Sixty years ago this April, NASA broke ground near Clear Lake to construct a new command post for manned space exploration. Located 25 miles south of Houston on the Gulf Coast, the Manned Spacecraft Center’s most pressing mission was to accomplish President John Kennedy’s audacious goal to send a man to the moon and return him safely.

The project was part of the 1960s Space Race, a Cold War showdown between the United States and the Soviet Union. Along with demonstrating who had the mightiest rocket power and superior technology, it could also tip the balance of military power toward one country or the other. Space—and specifically the moon—was a major front in the simmering conflict between the two adversaries. Thanks to NASA, Texas was on the front lines.

An aircraft transports Spacer Shuttle Endeavor with Clear Lake in the background. Photo courtesy NASA.

The 1,620-acre Clear Lake site was ideal for NASA because of its year-round temperate climate, access to large waterways, and proximity to Rice University and University of Houston; plus, Ellington Air Force Base was nearby. It would take two years to build the campus—renamed the Lyndon B. Johnson Space Center in 1973—but the clock was ticking on Kennedy’s moon challenge. Houston proved to be the logical choice for temporary workspaces. To jump-start the process, NASA took what it could get—warehouses, office space, even apartment buildings. In return, during this brief but intense period of relocation, Houston embraced the space program, even branding itself “Space City.”

“Kennedy was a master salesman for space,” says Douglas Brinkley, history professor at Rice and author of the 2019 book American Moonshot: John F. Kennedy and the Great Space Race. “He was able to sell going to the moon as a way to turn the South into a technological zone, and the greatest beneficiary was Houston. Today, the word ‘Houston’ is synonymous with ‘mission accomplished.’”

In March 1962, Robert Gilruth, the Manned Spacecraft Center director, opened a provisional headquarters inside the Farnsworth & Chambers Building, now home to the Houston Parks and Recreation Department. NASA employees also leased space for offices and labs at places such as the Gulfgate Shopping City (later demolished) and a Canada Dry bottling plant (now a carpet store). An apartment building on Beatty Street, in the southeast part of town, housed the agency’s Technical Information Division.

Houston’s population already exceeded 1 million people when NASA arrived, but the roughly 3,000-plus employees who eventually moved to the area were influential beyond their numbers. While Texans filled some positions, the country’s sharpest minds in space technology converged on Houston for jobs like flight controller and aeronautical engineer. There were also clerical staff, administrators, and mathematicians known as “computers,” mostly women who hand-calculated vital, complex equations for each mission.

Houstonians welcomed the new arrivals with open arms and pocketbooks.

“People wanted to be involved with NASA,” says Jennifer M. Ross-Nazzal, historian with Johnson Space Center. “Companies offered office space, Joske’s offered drapes for offices, Continental provided receptionists. They were offered cars—and we’re talking procurement people, not astronauts, not even engineers—just the advance people charged with setting up the site.”

Jerry Bostick, who moved to Houston in 1962 to work for NASA as a retrofire officer and flight dynamics officer, says department stores freely handed out credit cards to the new arrivals. “They had welcoming parties almost every week in places like the Shamrock Hilton [demolished in 1987], Glenn McCarthy’s Cork Club [now closed], some at the Music Hall [now a performing arts space].”

The Houston Homebuilders Association even offered the first astronauts free houses worth $24,000, according to a 1962 United Press International article, but NASA deemed that a bit much.

Still, Houston’s 1962 Fourth of July parade and barbecue thrown for NASA employees was a hit. When President Kennedy visited Rice University that September, declaring the U.S. must be “the world’s leading space-faring nation,” he appealed to Texans’ sense of pride to get the job done. When Kennedy was assassinated in Dallas 13 months later, Lyndon Johnson, a Texan from Johnson City, became president. He bolstered the administration’s commitment to the Space Race, declaring: “I do not believe that this generation of Americans is willing to resign itself to going to bed each night by the light of a communist moon.”

The idea of exploring the moon was kicked around during President Dwight Eisenhower’s administration in the 1950s, though Eisenhower feared the moon would become a nuclear-missile launchpad. But after the Soviet Union launched Sputnik, Earth’s first artificial satellite, in October 1957, the U.S. pivoted toward making a moon landing a reality.

Beeping its way across low-Earth orbit, Sputnik fascinated and frightened Americans. Biographer Robert Caro described then-Sen. Johnson as feeling “uneasy and apprehensive” as he tried in vain from his Hill Country ranch to spot the sphere cruising the sky over Texas. It didn’t ease Johnson’s mind when the Soviets tested a hydrogen bomb two days later. He held hearings about space and missile activities, chaired the Special Committee on Space and Aeronautics, and urged Eisenhower to sign the National Aeronautics and Space Act into law, establishing NASA. Under Kennedy, Johnson headed the National Aeronautics and Space Council. In April 1961—the same month Soviet cosmonaut Yuri Gagarin became the first human to orbit Earth—Johnson recommended to his boss that America shoot for the moon.

The federal government considered 23 sites for a new Manned Spacecraft Center, but there was no real contest. In Clear Lake’s corner stood Vice President Johnson, Speaker of the House Sam Rayburn, of Bonham, and Texas congressmen Bob Casey and Olin Teague. Albert Thomas, who was chairman of the House Appropriations Subcommittee with responsibility for funding NASA, also pressed the case. On Sept. 19, 1961, NASA announced Clear Lake would become its new headquarters.

Eagle Landing

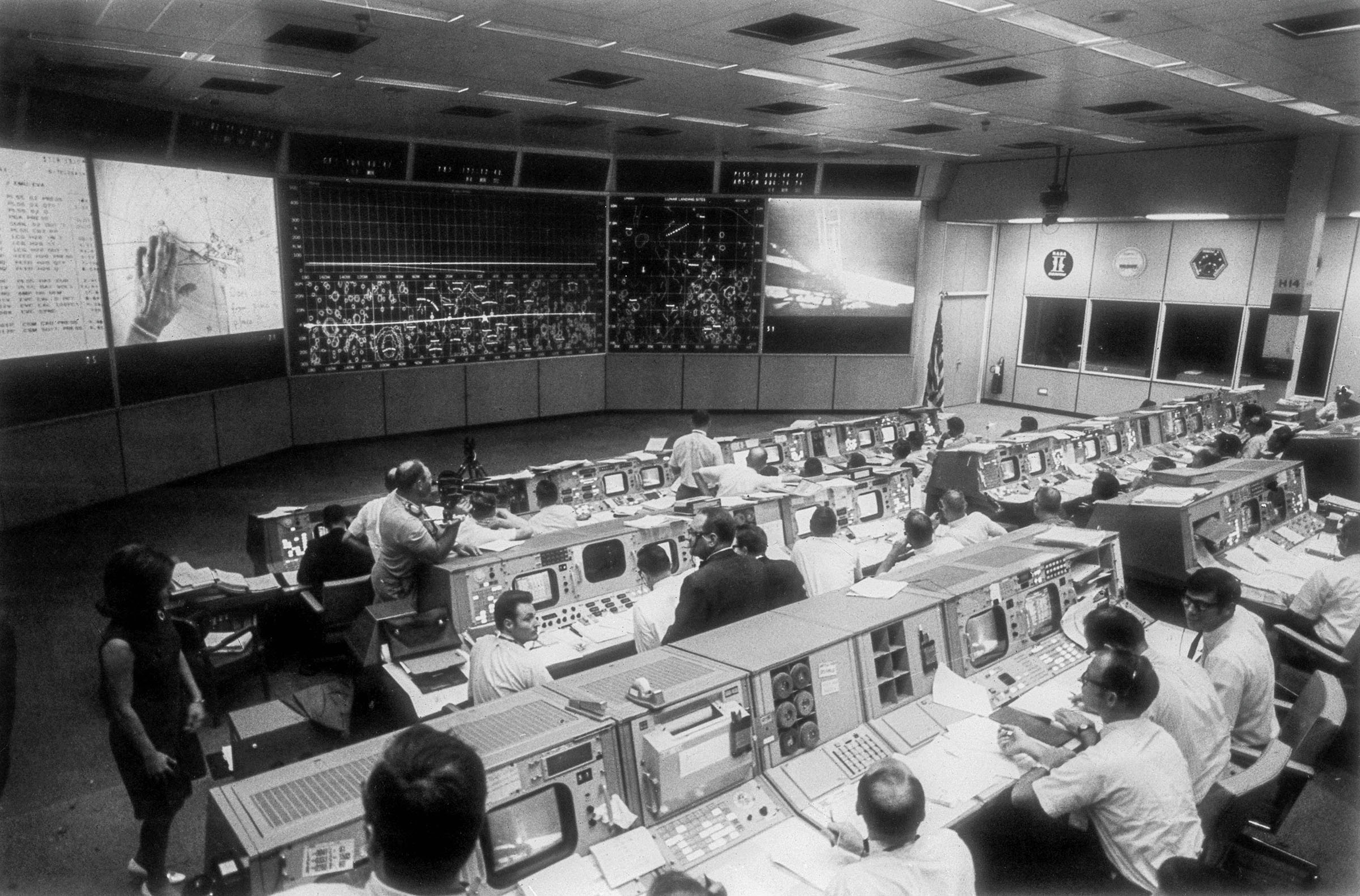

Not an astronaut or aerospace engineer? It’s still possible to see the Lyndon B. Johnson Space Center by exploring Space Center Houston, the visitor center. Along with history and technical exhibits and educational films, the center offers tram rides to the campus. The “Mission Control” tour visits the meticulously rebuilt Mission Control room from 1969, where visitors watch footage of the first moon landing and hear the timeless audio clip that includes, “Houston, Tranquility Base here. The Eagle has landed.” 1601 NASA Parkway, Houston. 281-244-2100; spacecenter.org

A NASA worker packs a model rocket in a converted bottling plant. Photo courtesy NASA.

By 1964, NASA employees were leaving Houston for Clear Lake. Laboratories, test facilities, and simulators were operating at the center while new shopping malls, restaurants, and schools transformed nearby communities like Clear Lake City, Friendswood, and Timber Cove.

“We bought a house in June 1964 in Nassau Bay, right across from the entrance to MSC,” recalls Gerry Griffin, a former NASA flight director. “I think we were the sixth family in that development. It didn’t take long to fill up the area.”

Griffin retired in 1986 as director of the Johnson Space Center and became president and CEO of the Greater Houston Chamber of Commerce. He speculates Houston’s excitement waned after NASA employees left the city for Clear Lake. Houstonians didn’t run into astronauts or engineers much anymore. “The Spacecraft Center didn’t get a lot of attention because it mystified some of the people,” Griffin says.

According to a Stanford Research Institute report published a year before the moon landing, the Clear Lake region saw growth in population, economy, and education as the Manned Spacecraft Center took root. The report even stated that Houston, which annexed the spacecraft center land in 1977, experienced a “dramatic change in character” because of its “pride in being a space center.”

Apollo 11 underscored the sentiment. On July 20, 1969, the mission reached the moon’s surface, and four days later returned its crew—Neil Armstrong, Edwin “Buzz” Aldrin, and Michael Collins—safely to Earth. Kennedy’s challenge was met. The Space Race was won.

More than 50 years later, Houston still proudly calls itself “Space City.”