The log cabin law office at the Sam Houston Memorial Museum in Huntsville offers a glimpse into Houston’s 19th-Century work environment.

After crossing the Red River into Texas in December of 1832, Sam Houston’s first stop was the city of Nacogdoches, the gateway to Mexican territory and home to some of the region’s most influential residents.

Discover more about Gen. Sam Houston

Houston arrived to Texas a well-known frontiersman, celebrated as a Tennessee governor and President Andrew Jackson’s protégé, but also notorious for the break-up of his first marriage. Charismatic and war-tested, Houston quickly established himself in Texas politics. He went on to sign the Texas Declaration of Independence, serve as Commander-in-Chief during the Texas Revolution, and hold office as Texas’ first elected president and then U.S. senator when Texas joined the United States. Houston’s legacy is felt across Texas, but his life here unfolded mostly in East Texas, from the decisive victory at the Battle of San Jacinto to the city of Huntsville, where he chose to settle. These days, Houston’s history is preserved at various East Texas sites that inspired him to describe his adopted homeland as “the finest portion of the globe that has ever blessed my vision.”

(Photo by Michael Amador)

In downtown Nacogdoches, now lined with antiques stores and gift shops, it’s easy to imagine horses and carriages navigating the streets, and a tall lawyer named Houston mingling among the townsfolk. Many future leaders of the Texas Revolution were already living in Nacogdoches when Houston arrived, including Charles S. Taylor, the great-great grandfather of future U.S. Senator Kay Bailey Hutchison. In Nacogdoches, Houston lodged in a boarding house owned by Adolphus Sterne, a German-Jewish immigrant and prominent local resident whom Houston had befriended in Tennessee. Houston hung his hat at Sterne’s house often, and, to fulfill a Mexican requirement for land ownership, was baptized into the Catholic faith in the front parlor of the Sterne home. Today, the 1830 Sterne-Hoya House Museum and Library is the oldest house in Nacogdoches still on its original site. The home is furnished with period antiques, family heirlooms, and exhibits about early Texas and the house’s other famous guests, including Davy Crockett.

The town of San Augustine, about 30 miles southeast of Nacogdoches, also lays claim to Houston’s influence. Houston maintained a law office in San Augustine and in 1836 was elected to be the commander of its soldiers, before being appointed Commander-in-Chief of all Texas forces. In July 1836, Houston rested at the San Augustine home of his friend and law partner, Colonel Phillip Sublett, to let his ankle heal from a musket-ball wound he had suffered at the Battle of San Jacinto. Houston spent his convalescence writing letters to friends and trying to figure out how to maneuver Texas into the United States. Later, during the days of the Republic, the citizens of San Augustine elected Houston to represent them in the Congress of the Republic between his two presidential terms.

Today, Sublett’s rebuilt home and numerous other historic residences are nestled among San Augustine’s towering pine trees with architecture that varies from Greek Revival and Victorian to simple frontier structures. Additionally, the city’s deep religious roots are represented by Memorial Presbyterian Church, the oldest Presbyterian church in Texas; Antioch Church of Christ, the oldest Church of Christ in Texas; and Jerusalem Memorial CME Church, the oldest African-American church in Texas. The cornerstone of the first Protestant church of any kind in Texas, today’s First United Methodist Church, was laid in San Augustine on January 17, 1838, under the supervision of the Masonic Lodge.

Sam Houston’s footprints extend to other points in East Texas, and perhaps the most important is the San Jacinto Battleground State Historic Site in La Porte. In addition to viewing the battleground where Texas won independence from Mexico on April 21, 1836, visitors can learn about the battle and Texas history at the San Jacinto Museum of History. The battlefield has been recently reinterpreted, with a boardwalk built out into restored Peggy Lake, which was the scene of the battle’s greatest carnage as fleeing Mexican troops attempted to wade to safety.

In his book, My Master: The Inside Story of Sam Houston and His Times, Houston’s carriage driver, Jeff Hamilton, said he took Houston to the battlefield for a visit several months before the General passed away in 1863. They sat for a time under the oak tree where Mexican General Santa Anna had surrendered.

“The General sat on the ground un-der the tree for a long time, never speaking to me or looking at me,” Hamilton recalled. “He had a far off look in his eyes, which I couldn’t help but notice were wet.”

One can only imagine what must have been going through Houston’s mind. The area is a picnic spot now. Nearby, visitors can take an elevator to the observation deck of the 567-foot San Jacinto Monument—a National Historic Civil Engineering Landmark—which provides one of the most commanding views in Texas. On clear days, from just beneath the 220-ton Lone Star of Texas, visitors can see the skyline of downtown Houston on the horizon, ships passing through the Houston Ship Channel, and the USS Texas, a battleship museum also located at the San Jacinto site.

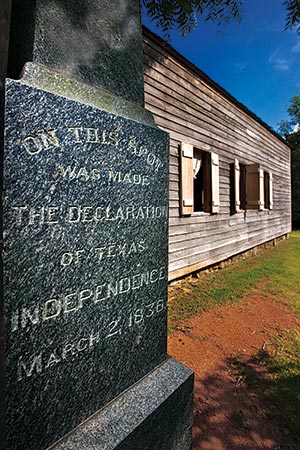

Houston’s history is preserved at sites like Washington-on-the-Brazos, which includes a replica of Independence Hall.

Not far away in the town of Liberty, where Houston maintained a law office during the 1840s, the Sam Houston Regional Library and Research Center—home to a museum and a collection of historic structures—houses a treasure trove of documents from early Texas. Several portraits of Houston, the executive record of Houston’s second term as president, and even an original painting by naturalist John James Audubon are among the center’s holdings.

However, the place where Houston and his third wife, Margaret, finally settled in 1847 was Huntsville, a Piney Woods town that Houston said reminded him of his childhood home of

Maryville, Tennessee. Driving along Interstate 45, it’s hard to miss Huntsville because of its 67-foot-tall, white-concrete statue of Sam Houston. There’s also a visitor center and gift shop at the base of the statue.

“We host thousands of visitors every year,” says Mac Woodward, Huntsville mayor and director of the Sam Houston Memorial Museum, which is located on the site of the Houstons’ old home in central Huntsville. “We have two of his homes here, his law office, an original hunting cabin of his that was built during the 1850s, and of course the museum, which was recently renovated.”

Each May, the museum hosts the Sam Houston Folk Festival (May 2-3 this year), a lively celebration of 19th-Century Texas. Living-history reenactors with their flintlocks and cannons, musicians, Native American dancers and craftspeople, blacksmiths, and a host of vendors set up shop for the event. It makes for a full day of honoring Texas heritage and Houston’s place in it.

Huntsville is still home to its most famous resident. Sam Houston is buried in historic Oakwood Cemetery, where a tree-shaded monument bears Andrew Jackson’s quote about his friend: “The world will take care of Houston’s fame.” It’s fair to say that East Texas certainly has.