Glenn Grieco adjusts the rigging on his model of the US Navy Brig Jefferson, a War of 1812 ship, at Texas A&M University. (Photo by Sam Craft)

The Texas A&M University Nautical Archeology Program is in the Anthropology Building, 340 Spence St. in College Station. Call 979/845-5242.

The Houston Maritime Museum, 2204 Dorrington St., opens Tue-Sat 9-5 with docent-guided tours until 4 p.m. Entry costs $8 (13 and older) or $5 (3 to 12, seniors); free for military members and veterans. Call 713/666-1910.

The Houston Maritime Museum sets sail to Buffalo Bayou

The Houston Maritime Museum is plotting a move to the banks of Buffalo Bayou, a fitting home that will expand 10-fold the museum’s space for events, archives, and exhibits, including a workshop dedicated to ship models.

The museum plans to break ground on the $50 million, 58,000-square-foot building in the first quarter of 2018 and open the new museum in the third quarter of 2019, Director Leslie Bowlin says.

“The growth of our museum is more than just as a repository for some nice artifacts and models,” Bowlin says. “It’s about the story we’re going to tell—how Houston fits into maritime history, how we arrived where we are, and what’s going on in the present and future.”

Naval architect Jim Manzolillo opened the Houston Maritime Museum near the Texas Medical Center in 2000 in a building that was once a residential home and a Greek restaurant. The museum has grown over the years and garnered the support of the local maritime industry, which is helping to fund the expansion.

The Houston Maritime Museum will be an anchor of the new East River mixed-use development, which will occupy the former KBR headquarters location on Buffalo Bayou, Bowlin says. The 150-acre site is on the north bank of Buffalo Bayou, about one mile east of downtown Houston.

Along with exhibits chronicling the world’s maritime history, the new museum will feature an interactive touch wall, a library, a workshop where visitors can watch ship-modelers at work, a restaurant, an event space that will host the museum’s popular lecture series, and an outdoor boat pond for remote-control boats and model sailboats.

“Houston was founded as a result of its connection to the maritime world,” Bowlin says. “So our mission is to tell Houston’s story and how it relates to the maritime world.”

The models are the handiwork of Glenn Grieco, director of the Ship Model Lab in A&M’s Center for Maritime Archeology and Conservation, part of the Nautical Archeology Program. One of the rare craftsmen to build ship models for a living, Grieco spends his days sawing, rigging, studying, and generally bringing to life miniature replicas of historic ships excavated by the university’s nautical archeologists. His ship models and those found in museums across the state interpret the world’s maritime history and provide thought-provoking portrayals of the life and times of our seafaring ancestors.

“In addition to what we learn about the actual construction techniques used to create the vessels that mankind has used for thousands of years, we also get a good look at what life was like for the people using the vessels,” Grieco says. “Understanding ships and the shipbuilding industry teaches us a lot about the economy and life at a specific time.”

Grieco’s models make their way into collections around the country, including several that are on display in the Nautical Archeology Program hallway on campus and at Texas museums. Visitors are welcome in the Anthropology Building, where glass cases exhibit everything from artful, two-foot wooden models of Chinese Yangtze River junks to an elaborate, six-foot Grieco model of the US Navy Brig Jefferson—which patrolled Lake Ontario during the War of 1812—and artifacts from an 11th-century Byzantine Empire shipwreck excavated by A&M archeologists on the coast of modern-day Turkey.

At the Bullock Texas State History Museum in Austin, a second Grieco model of French explorer La Salle’s La Belle complements an exhibit of the rebuilt hull of the ship that wrecked in Matagorda Bay. At the Texas Maritime Museum in Rockport, a third Grieco

La Belle rounds out an exhibit about La Salle’s ill-fated attempt to establish a settlement at the mouth of the Mississippi River. While La Salle’s expedition failed, news of the French foray into Nueva España prompted 18th-century Spain to expand its control over territory that would eventually become Texas.

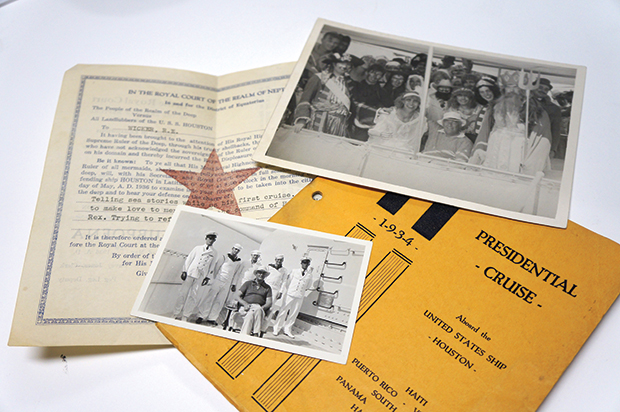

Photos and documents from President Franklin Roosevelt’s first cruise aboard the USS Houston. (Photo courtesy Houston Maritime Museum/©Lauren Anderson)

“I’ve written a lot of books on maritime history, and I sometimes use the models as a way of learning more about how the ships operated,” says Mark Lardas, president of the Gulf Coast Ship Modelers Society. For example, Lardas built a model of La Pinta—one of the ships Christopher Columbus sailed across the Atlantic Ocean in 1492—to help resolve questions he had about La Pinta’s rigging.

“I enjoy getting away from computers for a while and working with my hands,” says Lardas, an engineer by day. “Plus it’s an opportunity to tell a story because I tend to build dioramas of ships, rather than just the ship.”

Members of the Gulf Coast Ship Modelers Society meet once every two months at the Houston Maritime Museum to give presentations about their work and exchange tips and ideas. It’s a natural setting for the group, considering the museum is home to the state’s largest display of ship models with 178 in its exhibit rooms (and dozens more in storage). Society members have contributed models to the museum’s collection and also help maintain the small-scale vessels, which range from tiny ships in bottles to models that are as big as six feet long and equally as tall.

Having fun in Kids Cove at the Houston Maritime Museum. (Photo courtesy Houston Maritime Museum/©Lauren Anderson)

The Houston Maritime Museum also highlights its hometown’s vital link to the maritime world with the exhibits Energy Industry and Houston’s Story: From Bayou to Ship Channel.

“Many people in Houston don’t even know that we have a port, but the ori-gins of Houston are a maritime story,” Director Leslie Bowlin says. “The exhibit talks about the progression of Buffalo Bayou into the Ship Channel it is today. That’s really Houston’s gateway to the rest of the world.”

A model of the paddleboat Laura recalls the efforts of Houston founders August and John Allen to prove that Buffalo Bayou was commercially navigable. In 1837, they orchestrated Laura’s voyage from Galveston Bay to Houston. The exhibit also chronicles Houston’s role as a shipping port in 19th-century cotton trade; the opening of the Houston Ship Channel on Buffalo Bayou in 1914; Houston ship-builders’ contributions to World War II; and modern-day shipping commerce. Intricate models of a WWII infantry

landing craft, a channel pilot boat, tankers, and barges illustrate the story.

Bowlin says the ship models give visitors a better understanding of the scale of historical sailing vessels and how they operated and evolved over time. “From an artistic standpoint, they’re quite beautiful,” she says. “People really enjoy looking at them, and they’re cool aids for explanation.”

Back in College Station, Grieco is shipping his two models of the steamboat Heroine to museums in Oklahoma, and his latest La Belle model is taking shape for display at A&M. He’s also working on a model of a Colonial-era Hudson River sailing ship. After

the attacks of September 11, 2001, excavators found the sloop’s wreckage buried under the site of the World Trade Center towers; archeologists believe the boat was junked in the 1790s and used as landfill.

With each model, Grieco explores another slice of history through the prism of boats.

“One of the interesting things about it is that all of the technology of the day was incorporated into a ship,” Grieco says. “A large ship was a society in itself. If it was a large enough ship, you needed to have a blacksmith, a cook, doctors—it incorporated everything.”