Good Neighbors

In South Dallas, a father and son reconnect with the forgotten soul of the city

My father and I pulled into The Market at Bonton Farms in South Dallas to grab lunch before our trip to the old neighborhood a few miles away. This was at the beginning of the year, after a long stretch in quarantine. In the “before times”—before the pandemic, before Dad’s health declined—this was something we did regularly.

We would drive down to Bexar Street, to where it dead-ends into the Great Trinity Forest and a Trinity River levee—one of Dallas’ most beautiful natural treasures. There at The Market, we would have a bite for breakfast. Then we would head home, toward North Dallas, by retracing my father’s childhood steps along memory lanes called Park Row, South Boulevard, and the former Forest Avenue long ago renamed for Martin Luther King Jr.

For more than a year, we had spent precious few hours together in the same space, though my parents live only 5 miles from my house. But for our sanity, we had decided to mask up, gas up, and head to Dad’s South Dallas motherland, which some current residents call The Brotherland.

“Whoawhoawhoa,” my 77-year-old father, Herschel Wilonsky, moaned through his mask as we approached our destination. The farm and market reside atop the former Turner Courts housing project, which was once so violent even cops stayed away as soon as the sun threatened to set. Parked out front was a shiny, restored dark blue 1929 two-door Model A Ford with running boards and wheels painted daybreak yellow. It looked almost identical to the four-door Model A Dad rebuilt when he was a teenager and kept under a car cover until Mom convinced him to sell it last year.

Dad grabbed his wooden cane, which was once his father’s, and hustled for a closer peek. Bonton employee Clifton Reese is a native of this neighborhood and a family friend. He was standing outside, saying goodbye to some customers, when he saw Dad ambling toward the vintage ride. Clifton wanted to go in for a hug but settled for the requisite elbow bump. Dad asked who owned the Ford. Clifton told him it belonged to a man who was dining on the patio.

“Can’t miss him,” Clifton said. “He’s the one smoking the cigar.”

We placed our lunch order then headed out back, where a man who introduced himself as Cedric Sanders was puffing away at a table he shared with another man and two women. Dad asked Cedric about the car, and the two of them small-talked for a few minutes. My father told Cedric if he ever needed parts for the Model A, he had plenty stashed in his garage. Dad told him they were remnants of the inventory from the auto parts store he and his father once owned on nearby Second Avenue down the street from Fair Park.

“Wait a second,” said Cedric, his eyes and grin widening. “You’re S&W Auto Parts!”

My father grinned beneath his mask and said, yes, he was one of the Ws in S&W Auto Parts, which he reluctantly shuttered in 2009 before heading into an unexpected retirement. Cedric just about passed out at this realization. He explained he had been a customer of my father’s years ago. I hear this often whenever I walk around South Dallas, likely because my father spent more than half a century on Second Avenue.

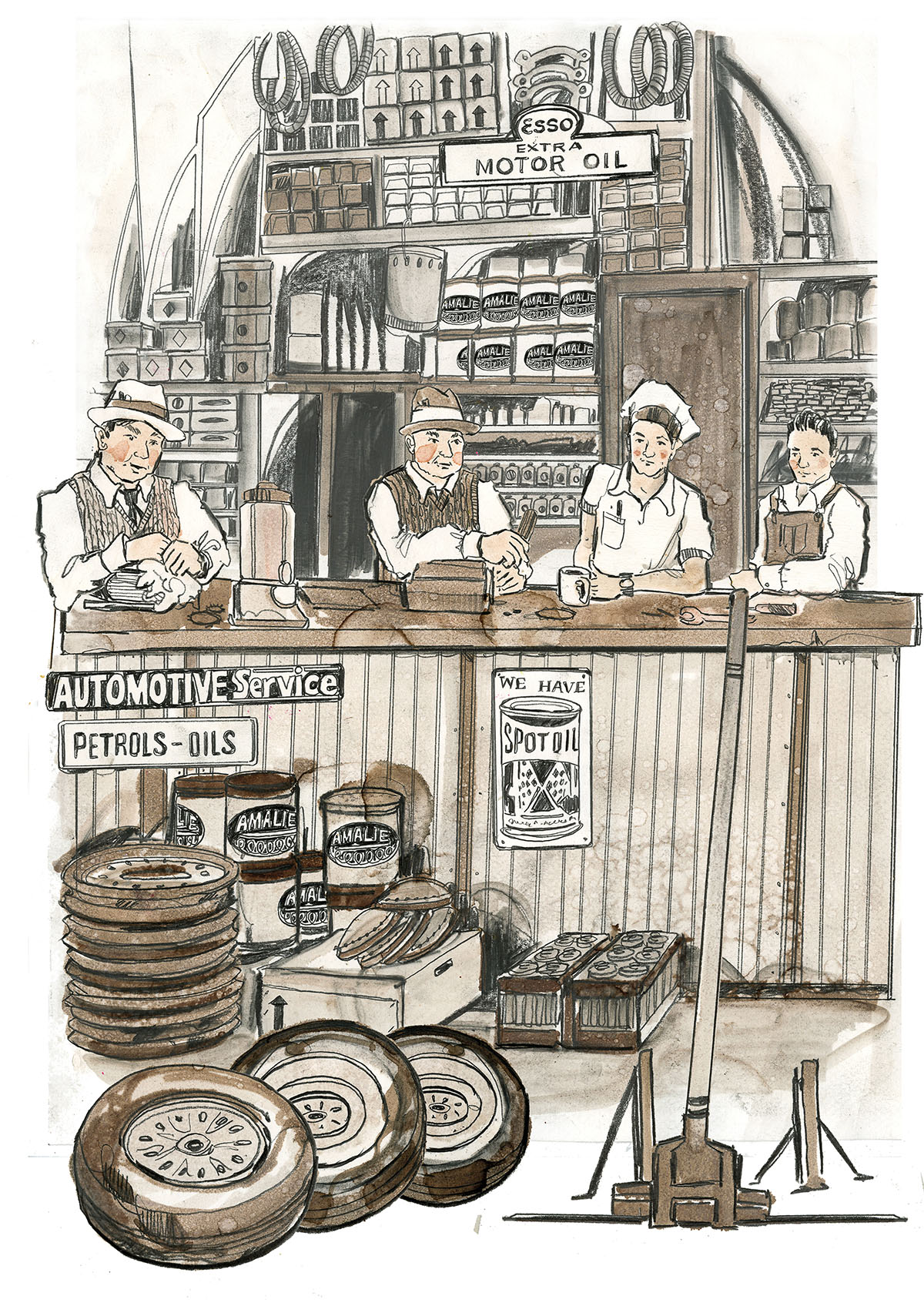

I love that these men remember my father, a bald, bearded white Jew with a voice like Big Tex who inherited a business he never planned on running and stayed there until it was time to go. It moves me because of how much their affection and fond memories move him. He spent most of his life standing behind a rotting, stained chipboard counter for 10 hours every day. In the mid-1950s, my grandfather Harry Wilonsky, like all the other South Dallas Jews of that era, moved his wife and son to the cheap, wide-open, white-open spaces of North Dallas. At the same time, he moved the parts store from Elm Street in Deep Ellum near downtown, its home since 1932, to nearby Second Avenue. So, he never really left South Dallas. And it never left him.

When my grandfather moved the store in 1955, Second Avenue was still thriving, a lively boulevard filled with nightclubs, groceries, and restaurants. Paw-Paw, as I called him, knew every shopkeeper on the street, among them Jack Repp, a Holocaust survivor who owned a dry-goods store across from the parts store. Before he died last year, Jack told me he liked to visit with my grandfather because they could speak to each other in Yiddish. That was a sound not often heard in Fair Park back then.

I spent high school summers working at the parts store in the early and mid-’80s, selling U-joints and carburetors and brake pads to “shade tree” mechanics for whom the store doubled as a neighborhood hangout. Once, a longtime customer walked in with a pistol aimed at my dad and his father. I forget why now. But Dad escorted him out, his arm over the man’s slumped shoulders. The customer came back a few days later, as if nothing had happened.

I used to think it would have made for a good workplace sitcom, like Barney Miller, as tense as it was tickling. Dad employed a long-haired bass player named Olin, who spent nights gigging at a joint called Mother Blues on Lemmon Avenue; a 6-foot-11 scoundrel called Slim, who stole from Dad on occasion and was eventually shot to death in his car; and a good old boy named Kirk, who Dad affectionately called Putz.

Despite weekends and long summers behind the counter, I learned next to nothing about the parts business or, for that matter, how cars work. But I liked working alongside Dad and spending time with my grandfather. Paw-Paw would take me on deliveries in his El Camino, which smelled of 43-year-old ashtray, or to lunch at the Old Mill Inn at Fair Park, or on long drives around the neighborhood he loved and refused to leave even as it came undone. He was a generous man who gave little bottles of bourbon to regulars at Christmas. His customers were his friends, his people, his mishpucha.

By the time I worked there, and my younger brother after me, S&W smelled of cigarettes and grease and sweat. And it stood along a stretch of avenue whose slow, steep decline meant blocks of liquor stores, no-tell motels, biker-club headquarters, and cracked empty lots. Much like it is today.

In the ’50s, when the community shifted from Jewish to Black residents, city and state officials split the neighborhood in half by running an expressway called South Central straight through it, just past the Forest movie theater. Now, the neighborhood on the west side of the freeway is mostly blank real estate with for-sale signs teasing investors and developers with their blueprints for shoebox condos. There’s a lot of that in South Dallas these days.

I’ve read and heard enough about the old neighborhood to become nostalgic for the Second Avenue I never saw, the South Dallas I never knew. Where middle-class Black and white residents worked and lived and drank and ate. Where Jimmy’s Food Store, an Italian grocery that’s now an East Dallas landmark, first operated as Morningside Super Market. Where Buck Rogers serials played at the Dal-Sec movie house, which the city bulldozed in the ’60s, along with half the neighborhood, to make room for a Fair Park parking lot.

When my son, a freshman at the University of Texas at Austin, was younger, we spent almost every Saturday in this part of town. We’d get lost on side streets, searching for remnants of what used to be. We hunted for ghost signs on old buildings advertising long-gone shops, walked around the historic Bama Pie building that stands empty, and rooted around for bricks that said “BUILDERS,” the name of my grandfather’s old brickyard, once located where the Mesquite Rodeo now stands.

My father, who occasionally forgets what happened five minutes ago but remembers every detail of 10,000 yesterdays ago, is nostalgic for the lost city he knew better than most. This is the city my grandfather and his brothers escaped to, lived in, and helped build. The Wilonskys had dry-goods stores and wrecking yards and parts shops in Deep Ellum, even a pawn shop called Dallas in downtown. I’ve heard the stories, seen the faded photos, even had a few drinks in Uncle Eli’s old clothing store in Deep Ellum, now the Anvil Pub. The auto parts store on Second Avenue is still there, too, painted over and bricked up, now a church for homeless people.

Harry Wilonsky, a short man born in 1904 in Šakiai, Lithuania, was the last of four brothers to come to Dallas. He came to this country when he was just 18, speaking no English, and though he was in Texas most of his life, he never shed his Eastern European accent. He died at 83 in March 1988 mumbling about the deep snows of home.

He and my father also spent more waking hours on Second Avenue than they ever did in the place called Preston Hollow, the North Dallas neighborhood they moved to in the ’50s. Maybe that’s why people like Cedric Sanders still remember the store and my father. Because Dad never left. Because he never wanted to.

After lunch at Bonton, Cedric took Dad outside to look under the hood. Dad used his cane to point out what had been replaced and what was original. He told Cedric if he ever needed the original spark plugs and not those modern-day fill-ins, just give him a ring. Dad handed him a S&W Auto Parts business card. The old Second Avenue phone number now goes to Dad’s cell phone.

My father beamed as we drove the 3 miles from Bonton to his old house, a bungalow on Park Row. It was as though he’d just been reunited with long-lost family members. For the first time in a year, I grabbed his hand and gave it a squeeze.

For the first 11 years of his life, from March 1944 until the summer of ’55, Herschel Wilonsky lived at 2521 Park Row, between Atlanta and Edgewood streets, about a mile from the front gates to Fair Park, home of the State Fair of Texas. To this day, my father can stand in front of his boyhood house and tell you who lived where. “That was the Ablons’ house,” he said that afternoon. He nodded toward bungalows along the block. “And that was the Jacobs’, and that was the Levines’, and that was the Chesnicks’.”

This is a historic neighborhood; it says so on the plaque planted along South Boulevard in 1981, telling the story of Jewish merchants who came to South Dallas but eventually moved north and were replaced by “prominent Black leaders of the Dallas area [including] educators, lawyers, merchants, clergymen, doctors, and business executives.” Every June, beginning in 2012, I ferried the Dallas Morning News’ summer interns on a daylong city tour, and this marker was always our first stop.

I’d gone to work for Dallas’ only daily after 20 years at the Dallas Observer and, before that, two at the Dallas Times Herald. In the spring of 2016, I was promoted to city columnist. It was a dream gig for a native son who collects every old book and bottle and knickknack and scrap of yellowed paper with the word “Dallas” on it.

During my tenure, I probably wrote more about South Dallas than any other part of town. Its past and present have been so poorly misrepresented that it’s too often portrayed as a place without much future. I used to worry that the interns, a mix of high school and college students mostly from out of town, would hear bad things about South Dallas during their brief stays here, that the ignorant and scared who refused to step foot down here unless it’s State Fair time would send them home with the wrong idea.

Maybe it’s not the heart of the city—shiny and glitzy, big and brand new—but I’ve always thought of South Dallas as its forgotten soul. This is where Ray Charles lived in the 1950s, at 2642 Eugene St., while putting together his band, whose members, among them David “Fathead” Newman, learned jazz at nearby Lincoln High School and played late-night gigs at the American Woodman Hall off Oakland Avenue, now named for Malcolm X. Most people in Dallas have no idea what happened here. Or what happens here.

During a visit a couple of years back, I saw an acquaintance sitting on the front porch of the bungalow next door to Dad’s old house. Lincoln Stephens, who runs a nonprofit promoting diversity in media and advertising, called us over and invited Dad to sit with him on his front-porch swing. They discussed bringing some of the old white residents down to meet the current Black ones. “I would love to have an exchange of history and shared knowledge,” Lincoln said.

Lincoln had so many questions about his neighborhood and his house, which he likes to say is full of an energy he can’t quite define. He asked who lived in his house when Dad was a boy. My father said it used to belong to a couple named Mike and Ginger Jacobs.

Mike was a Holocaust survivor from Poland who came to Dallas in 1951. His mother, father, two sisters, and two brothers died in gas chambers at Treblinka. A brother died fighting the Nazis. Some 60 to 70 relatives of Mike’s also died in camps. He spent most of his life here sharing horror stories with school children. Several times when I was a boy, he came to our classes to recount life amid so much death.

“That explains everything,” Lincoln said.

Another old friend, Keith Manoy, lives one street over from Lincoln, on South Boulevard, where the mansions are bigger and more ornate than the bungalows on Park Row. This is the street on which Stanley Marcus of Neiman Marcus—who went to the same high school as TV producer Aaron Spelling—was raised. This is where the houses were designed and built by architects still known in Dallas by their last names: Lang & Witchell, Overbeck, DeWitt.

Until a few years ago, Keith was Dallas’ assistant director in public works, responsible for long-range transportation planning, and was known for advocating for bike lanes in a city built for cars. He moved onto South Boulevard in 1990, in a house with a stained-glass window that makes it look more like a house of worship. There’s still a mezuzah on his door frame—a piece of parchment inscribed with Hebrew verses from the Torah and stored in a decorative case—serving as a reminder that a Jewish family lived here long ago.

“We refuse to take it down,” Keith said. “The history is so rich. It was Jewish, then Black. And that history has been preserved. It’s wonderful.”

Only a few blocks from Dad’s old house, no more than a two-minute walk from Park Row, there are blocks of empty lots where whole neighborhoods once flourished. The city promises to rebuild here. Until recently, an enormous tent city of homeless people had taken root in the shadow of where Big Tex stands for a few weeks each fall.

When Black people moved into South Dallas, the white Jews left via a newly poured expressway called Central, which followed the northward path of the old Houston and Texas Central Railway. The highway extended to Walnut Hill Lane, then a country road but now a six-lane thoroughfare. My grandparents and father moved to Walnut Hill in ’55. They weren’t the first to leave South Dallas, nor the last. They followed friends and family who had moved to Preston Hollow because the land was expansive and inexpensive. “It was white flight,” Dad said.

The neighborhoods around Park Row and South Boulevard have frayed at the edges: Some of the houses are boarded up or drug dens, while others have become Airbnbs or are in the hands of faraway owners renting them to temporary residents. There are also many empty lots. Yet Park and South endure. Young families are moving into these old homes. They are white, Black, Latino. A man from Pakistan appears to have moved in recently. A new wave not so different than the old is rejuvenating the landmark district.

Jeanette Bolden, who serves on the Landmark Commission’s South Boulevard-Park Row task force, lives with her husband, Charles, in Dad’s childhood home. The Black couple bought it more than 30 years ago from the woman who purchased it from my grandfather. The two of them grew up in South Dallas, and as a little boy Charles would mow lawns there, just to be near the homes and the people who lived in them.

“It was always his dream to get up here,” Jeanette said.

In the early ’90s, Charles, a carpenter, began repairing the house inside and out. Every time he made even the slightest alteration, a white man seemed to always show up and slow roll past the house.

“Who is this person?” Jeanette wondered. “He would slowly pass by, stop, keep rolling. Didn’t bother us. But he was always watching.”

Dad finally knocked on the door to introduce himself. Then it hit them who he was: the guy with the parts store on Second Avenue. He told the Boldens he wanted to buy the house if they ever sold.

“No,” Charles told my father. “This is for me to keep.” My father’s memories of the neighborhood, and his dreams of somehow recapturing them, were now Charles’ hard-won reality. So instead, Dad and I will just keep driving by.