In 1969, a San Antonio fried-chicken tycoon was struck by a life-changing idea: He would find, buy, and heal “the sorriest piece of land in the Hill Country.”

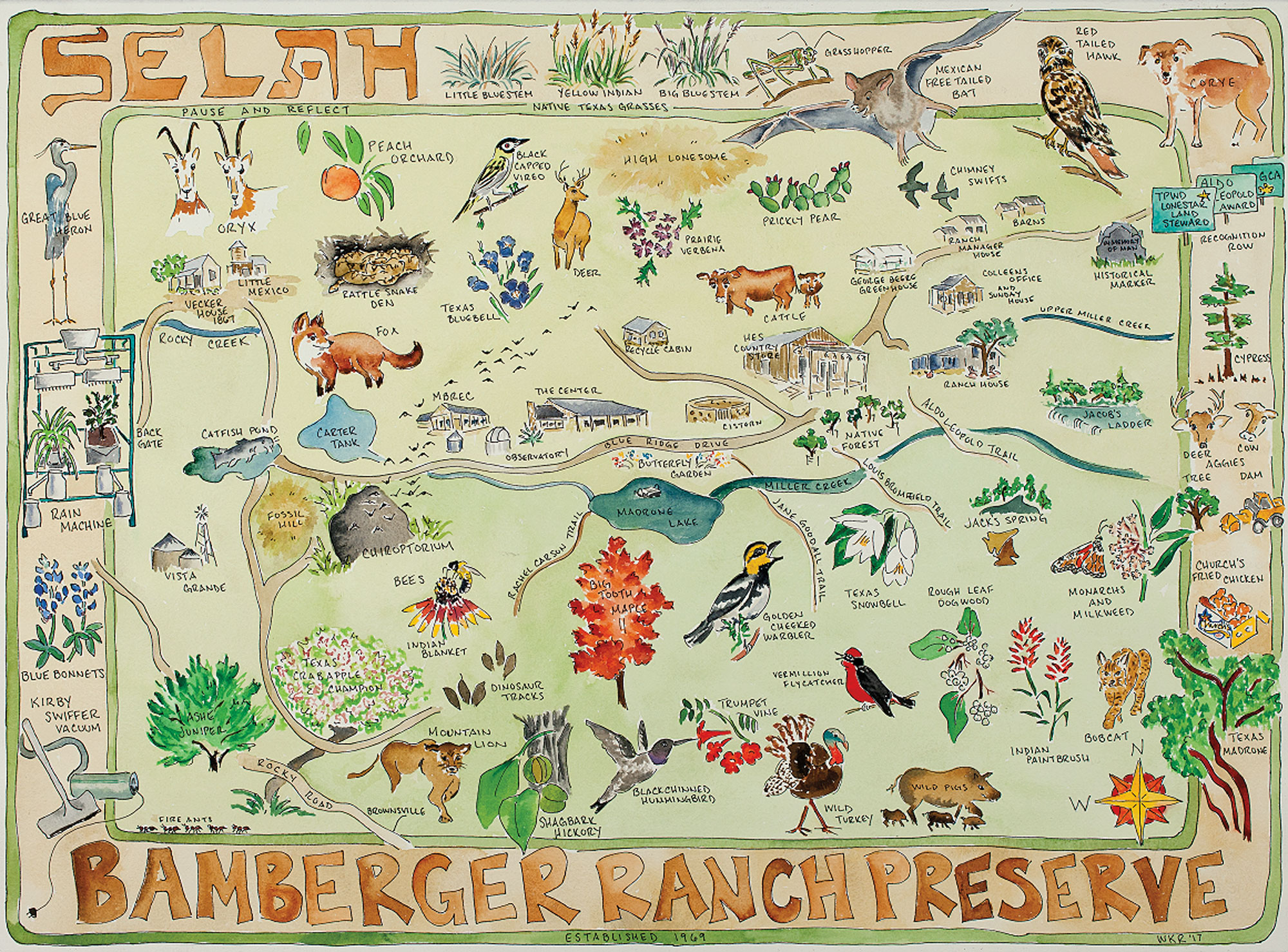

Now celebrating its 50th anniversary, the Bamberger Ranch Preserve sprawls across 5,500 acres of grassy hills and wildflower meadows in Blanco County. When visitors arrive May 5 for the annual family day and picnic, they will repeatedly drive across a perennial stream that cascades through a series of waterfalls and deep pools. Fields of Indian blankets practically glow at sundown this time of year, and the leaves of the bigtooth maples burst into brilliant hues of red and gold each fall. The ranch, which also goes by the informal name Selah, is widely celebrated as one of the largest and most influential efforts to restore a classic Texas landscape. When J. David Bamberger launched his project half a century ago, however, Selah was a worn-out wasteland. Many thought he was a crackpot—not that Bamberger minded.

“I’ve lived my life being different,” says Bamberger, who began his career as a door-to-door vacuum salesman and went on to co-found Church’s Fried Chicken, the first Texas-based fast food chain to expand nationwide. When the company went public, Bamberger became a wealthy man. At 40 years old, he was living in San Antonio and ready for a new purpose.

“Money no longer meant anything to me,” Bamberger, now 90, recalls, “and I knew that the opportunity to change the direction of my life had been presented to me.”

Click the image above to view more photos.

The chicken mogul thought back to his childhood in the Amish country of Ohio. He’d grown up dirt poor during the Great Depression, with no running water or electricity. “Everything we ate growing up came either from what we could grow in our garden or gather in the woods,” he says, noting that his mother Hester—Hes for short—was an early environmentalist. When Bamberger was a teenager, his mom gave him a copy of Pleasant Valley, a popular nonfiction book that chronicled author Louis Bromfield’s pioneering efforts to cultivate and restore farmland that had been overworked for generations in rural Ohio.

The Texas Hill Country had also been severely neglected. When the first big wave of settlers arrived in the 1840s, they encountered a sea of grass as far as they could see. Ashe juniper, commonly called cedar, was largely confined to the steep slopes of canyons, and springs flowed freely. In less than three decades after the settlers’ arrival, however, the grass was gone—overgrazed by cattle, sheep, and goats. Much of the thin soil washed away. Cedar, which needs minimal topsoil to take root, spread out of the canyons and choked the hillsides. The brushy tree, a notorious consumer of rainwater, sucked up so much moisture the Hill Country was left dry and barren. When President Lyndon B. Johnson was born on Aug. 27, 1908, less than 10 miles from what would become the Bamberger Ranch, the Hill Country was one of the poorest economic regions in the United States.

A Legacy of Friendship

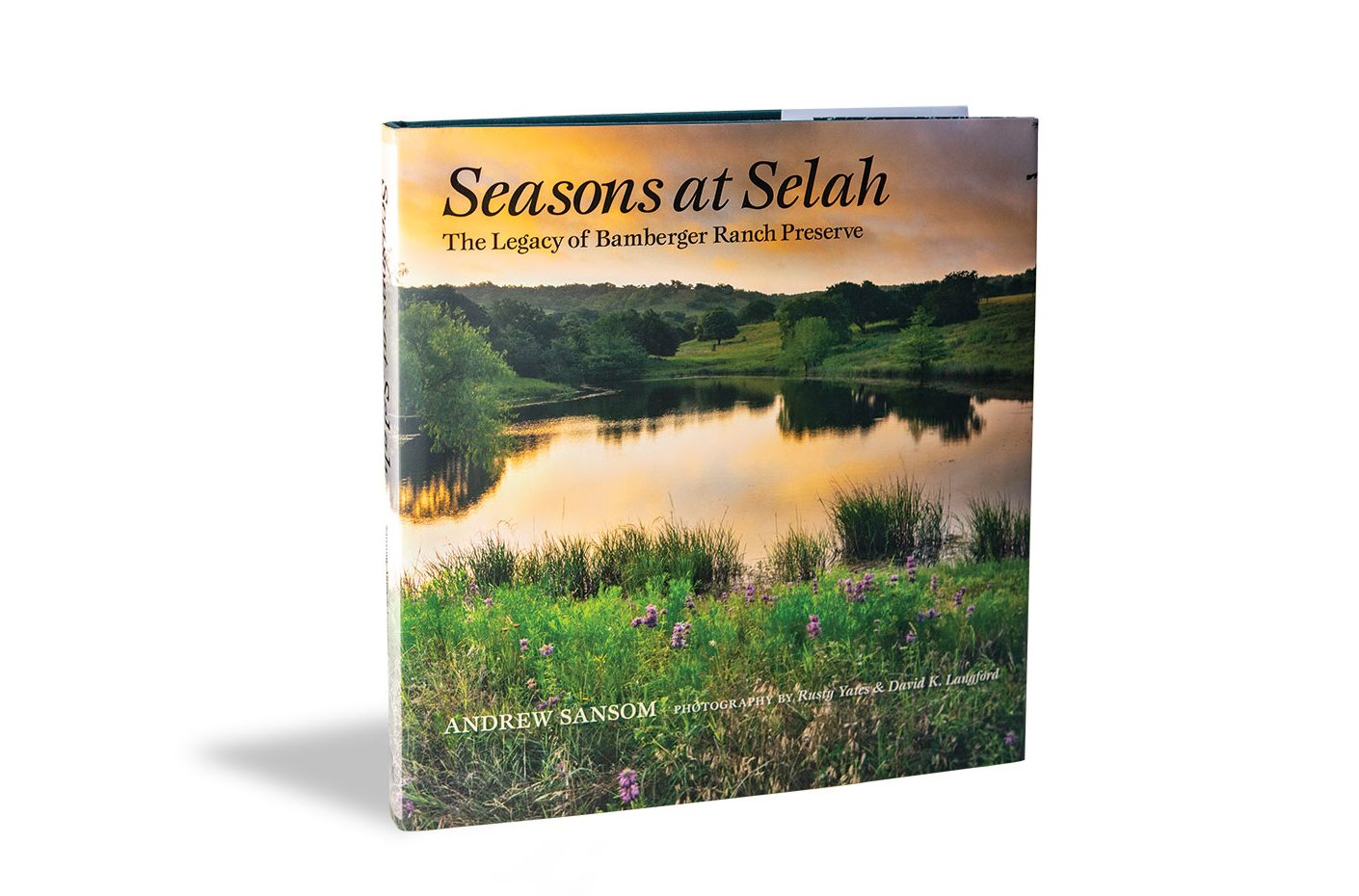

Two of the state’s most respected conservationists met in the early 1980s when Andrew Sansom, then running the Texas office of The Nature Conservancy, invited J. David Bamberger to watch the evening emergence of bats from Bracken Cave, north of San Antonio. “I’ll bring the chicken,” replied Bamberger, then the CEO of Church’s Fried Chicken.

There began a relationship spanning more than three decades, Sansom recounts in his new book, Seasons at Selah: The Legacy of the Bamberger Ranch Preserve. In the early years, as the two men walked beside Selah’s clear streams or swam in its largest lake, Sansom writes, “I began to realize that my new friend … was in the process of creating something extraordinary on his ranch, an inspired effort that would transcend our lives.”

Fast forward to 1969, and Bamberger knew he couldn’t fix the entire Hill Country. But he wanted to use his chicken riches to revive his own piece of it, building on the early example set by his mom and by Bromfield, whose Ohio farm has been turned into a state park that educates others about land stewardship.

“I contacted several ranch brokers who tried to sell me spreads with huge houses, airstrips, and other fancy infrastructure,” Bamberger recalls. “I couldn’t get them to understand that was not what I was looking for.” So he reached out to the U.S. Department of Agriculture. He told a soil conservation agent he was looking for the most played-out ranch in the region.

“Well, this is Texas, and there is plenty of that,” the agent told him. “I just hope you’re not planning on raising any cattle.”

Bamberger and his pal Corye. Photo: Chase Fountain/TPWD

He was, in fact. Bamberger purchased 3,000 acres near Johnson City, north of San Antonio and southwest of Austin, which he later expanded by 2,500 acres. The ranch was mostly bare ground or infested with cedar. There was no grass and absolutely no live creeks, springs, or ponds. When Bamberger drilled a series of water wells, not one of them produced a drop.

Undeterred, Bamberger assembled a group of Texas A&M-educated professionals—he called them his Cow Aggie, his Tree Aggie, his Deer Aggie, and his Dam Aggie—and went to work. With a used bulldozer, they attacked the cedar, learning as they went to avoid the steeper slopes, taking care not to exacerbate erosion. Then they planted native grasses to hold the topsoil in place. Bamberger, his sons, and his team bought so much native seed from local suppliers they were accused of cornering the market, a feat he jokingly admits he never achieved with fried chicken.

Slowly, the landscape at Selah began to change. As the cedar was removed and grasses took root, the hills took on a vibrant green hue. Instead of running off, the raindrops increasingly were absorbed into the soil, recharging a shallow aquifer just below the surface and, little by little, resurrecting the springs.

Click the image above to view more photos.

Today, there is water literally everywhere on the ranch, from the headwaters of Miller Creek, a tributary of the Pedernales River, to more than two dozen ponds and lakes fed by natural springs throughout Selah. Five families can live at the ranch on water supplied not from wells but from springs that didn’t even exist prior to Bamberger’s arrival.

To be sure, land stewardship is more complicated than clearing brush and planting native grass. In some areas, the groundwater is simply too deep to ever emerge as springs. And old-growth cedar has its place in the Hill Country, both to stabilize steep banks and hillsides and to provide important habitat for endangered birds such as the black-capped vireo. The evidence at Bamberger Ranch speaks for itself, however, and Bamberger’s efforts have helped lead to the widespread acceptance that rampant cedar growth does in fact deteriorate groundwater, the source of the Hill Country’s once-prominent springs.

The healing of Selah, named for an ancient Hebrew word thought to mean “pause and reflect,” is “a story of stewardship and a renaissance of restoration,” says Carter Smith, executive director of the Texas Parks & Wildlife Department. The ranch has received some of the nation’s highest awards for land stewardship, and Bamberger, always the brilliant salesman, has attracted dedicated helpers from all walks of life to share in his toil in service to the earth.

“It doesn’t take a lot of cash to be a good land steward,” Bamberger is fond of saying, “but it does take hard work and dedication.”

Today his example has never been more important. Texas is losing rural and agricultural land faster than any other state. One of the biggest environmental problems the state faces is the continued fragmentation of family lands. In this context, the Bamberger Ranch is a beacon of hope.

Click the image above to view more photos.

By the early 1990s, the Selah restoration project was showing results. Bamberger had retired once and for all as chairman of Church’s Fried Chicken, and he was weighing whether to accept an invitation to serve on the board of Bat Conservation International, which had moved its headquarters from Milwaukee to Austin due to the sensational number of bats in Central Texas.

“Bat people are goofy,” Bamberger said at the time, but he soon became one of the nation’s most dedicated champions of these then-largely misunderstood creatures.

In 1992, the organization had acquired Bracken Cave in Comal County, which is thought to be the summer home of the largest concentration of mammals on the planet. With the help of his “Dam Aggie,” ranch engineer Leroy Petri, Bamberger installed a system of trails and other infrastructure at the cave to enable visitors to view the 20 million Mexican free-tailed bats that emerge to feed every summer evening.

“I was hooked,” says Bamberger—so hooked, in fact, that he came up with the idea to build his own cave to attract bats to Selah. “At that point,” he says, “people thought I was goofy.”

Today, hundreds of thousands of bats spend their summer in the ranch’s artificial cave, which boasts two names: One is “Bamberger’s Folly.” The other is the “Chiroptorium,” a term his wife, Margaret, coined with his son David by pairing chiroptera, the scientific name for bats, with the word auditorium. On certain evenings in late summer, the public is invited to watch the bats emerge, perhaps the ranch’s most captivating seasonal spectacle.

Not long before the bats arrived at the Chiroptorium, Bamberger was serving on Gov. Ann Richards’ Task Force on Nature Tourism when he coined another phrase: “people ranching.” It was meant to describe Selah’s growing effort to introduce city dwellers to the outdoors and to educate them in the importance of land and water conservation.

In Texas, where 95 percent of the landscape is owned by private residents, “people ranching,” or agritourism, can be an important source of income to farmers and ranchers across the state. Each year, hundreds of thousands of visitors come to Texas to hunt, fish, or birdwatch, and many of the best opportunities are on privately owned farm and ranchlands.

At places like Selah, such activities are more than a supplemental source of income. The ranch regularly welcomes the public for nature tours and bat viewings. Visitors can also attend landowner seminars, and children come for hands-on classes and summer camps in one of the most beautiful settings in the heart of the Hill Country.

It is increasingly children who are the ranch’s most important guests—a legacy of Margaret Bamberger, an artist and educator who married Bamberger in the 1990s. Margaret created the ranch’s educational programs and gave the ranch its credibility as an educational institution. Each year more than 3,000 kids from low-income schools and many more are brought to the ranch for outdoor fun and learning, and to experience what Bamberger calls “Selah Moments”—the opportunity for the next generation to pause and reflect while surrounded by the outdoors.

“There’s something special about teaching nature,” Bamberger says. “You can feel it in yourself. It’s called passion, and when you are talking, those who are listening will feel it too.”

Seventeen years ago, Bamberger established the Bamberger Ranch Preserve to protect Selah long after his death, and he retired last July as chairman of the preserve’s board of directors. Once derided as a crackpot, he is now hailed as a visionary. “Given the chance, nature can heal itself,” Bamberger says. “Nature can heal us.”

Visit the Bamberger Ranch Preserve

Public and private tours: Visitors can take a firsthand look at the results of a half-century of habitat restoration. They might also see dinosaur tracks, fossil beds, a herd of scimitar-horned oryx (a graceful African antelope that is extinct in the wild), examples of every tree native to the Hill Country, and plenty of bats on summer evenings.

Go deeper: The ranch offers a number of workshops on land stewardship, such as cedar management, water development, growing native grasses and trees, and managing for wildlife.

Family Day and Picnic: The ranch’s biggest public event each year offers tours and nature walks, ziplines and fishing lessons for children, fossil digs, wildlife presentations, arts and crafts, and a native plant sale.

May 5

10 a.m.-5 p.m.

$45 adults, $15 children, $135 families.

Proceeds benefit children’s educational programs at the preserve.

2341 Blue Ridge Drive, Johnson City

830-868-2630

bambergerranch.org