In the debut of Texas Highways’ new monthly essay, Open Road, novelist Sarah Bird writes about walking the trails of J. Frank Dobie’s Paisano Ranch in the Texas Hill Country with the ghost of Cathy Williams, the only woman to join the Buffalo Soldiers, the African American army regiment formed after the Civil War. Since 1978, when Bird first heard about Williams at an African American rodeo, she had hoped Williams’ remarkable but mostly forgotten story would be told. After almost 40 years of waiting in vain, Bird decided that she would have to tell the story herself. The resulting novel—her 10th—is an exuberant, mind-opening page-turner of historical fiction, Daughter of a Daughter of a Queen.

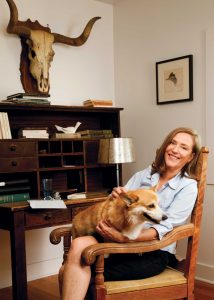

Photo by Sarah Wilson

Q: You learned about Cathy Williams in the late ’70s. Why did it take so long for you to write this book?

A: I kept pushing her away. I was astonished that her story hadn’t been told, but I was certain that it would be told at any moment by an African American writer, and hopefully an African American woman. I resisted writing it because of very sensitive issues of cultural appropriation. So I just kept pushing her away, and she kept coming back, and back, and back.

Q: How did she come back?

A: About 10 years after first hearing about Williams, I went to my childbirth classes, and Pam Black, who’s become a dear friend, was teaching the class. She came up to me and said, “You’re a novelist, aren’t you?” I said, “Yeah. I make my attempts.” She said, “I teach at a predominately black kindergarten, and we need more stories about heroes who look like our kids. I got this one great story about a woman named Cathy Williams.” And I said, “I’ve heard this story. I’m sorry to tell you it’s not true.” But then the next class she brought me copies of Cathy Williams’ enlistment papers, her discharge papers, and her application for pension.

Q: So now you knew she was real. But it still seems like there were a lot of things holding you back from writing the book. Like the right publisher.

A: I went to St. Martin’s Press, and Cathy Williams delivered unto me a fabulous African American editor, who adored the book and went to bat for it. It was very reassuring to have her read it. She’d tell me anything I’d get wrong, anything that’s the least bit offensive, and she was just completely supportive. She said, “This is the kind of book I got into the business to publish.”

Q: What has been one of the most important things you’ve learned writing from the perspective of a former slave turned Buffalo soldier? Has it changed you at all to write about someone outside of your identity?

A: You know, nothing about Cathy really felt outside of my identity. She just so inhabited me for so long. I write first person, and it’s like a method actor. I write what the characters tell me to write. She’d been talking to me for so long … it mostly had to do with portraying a woman in a man’s world, but add a layer of a formerly enslaved woman. Her perspective on things like the surrender at Appomattox was really important to me. Also, even though she was stationed in New Mexico, I moved her to Texas. This was important so I could have her comment on slavery in Texas, one of the least acknowledged members of the Confederacy, since virtually none of the war was fought on Texas soil. So there wasn’t the horrific destruction here that there was throughout the rest of the South. Instead of coming home to devastation, for example, the ranchers who’d turned their herds loose came home to bounteous herds of cattle, which then they rounded up and had the great trail drives of the 1870s and ’80s.

Q: The language in this book is so playful. I love all the expressions like, “She’s wild, wild as an acre of snakes.”

A: I had to do a tremendous amount of research to get those exactly right. I kind of got the genome and then would do something that fit the equation. But, man, all those phrases, I adore them. “Stunned as a goose with a nail in its head?” What?

Q: Yes! Here’s one. “He just stood there, cool as a frog’s belly.” Such language is so smart and creative, I’m so glad to know that many of them were actual sayings.

A: I’d say that the vast majority of them are. You also realize within that frame of reference what kind of metaphors people could make up. They had to be based on agriculture, mostly. Agriculture, nature, animals. That’s the thing I’m proudest of in this book is feeling like I got the language right, and also bringing in some of those great phrases.

Q: Well, there’s so much I learned form this book. I hope it will be taught in schools.

A: I’ve received some letters from teachers; they’re using it in classes. It’s good because it’s immersive. Novels are empathy machines. If you really surrender to the book, your point of view is changed drastically.

Q: That’s what it did for me. Losing myself in your writing, I felt this space opening up and Cathy Williams is there, teaching me what it might have been like, but through you, because you’re the one who took time to drudge through all the historical records, to really study the times and experiences of Buffalo Soldiers.

A: And I hope that without hammering a big history lesson home or anything political that readers can see the experience of what Texas was built on and what it meant for the enslaved people of Texas. They need to be honored.