Flipping the Script

What do we really know about Bonnie and Clyde and their legacy in Dallas?

By Sarah Hepola

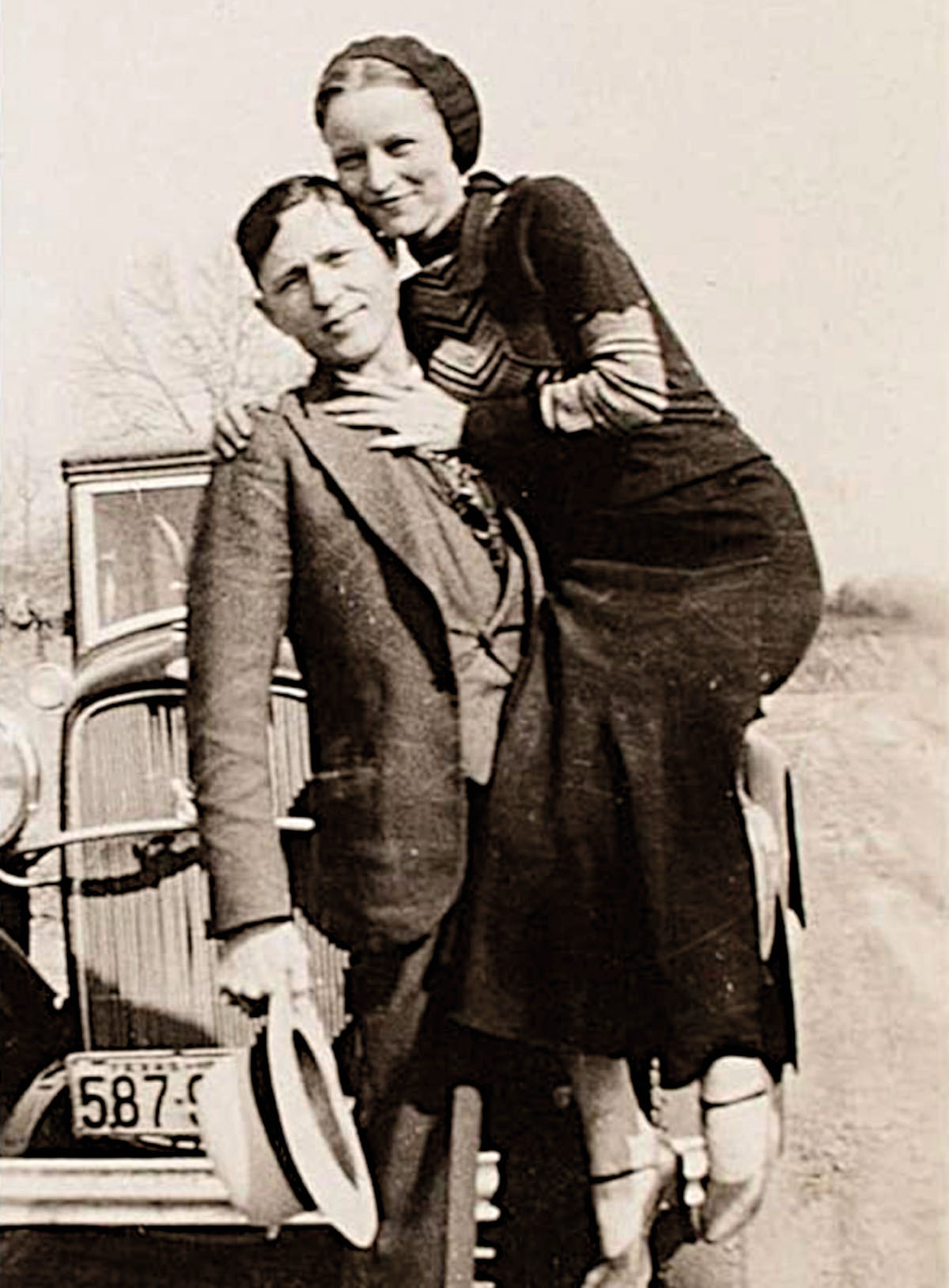

Bonnie and Clyde hamming in front of the camera, in 1933, turned them into media sensations. Photo courtesy FBI.

“Scene” might be a stretch for what’s about to happen. Actors in period costumes dart out the front door of Farmers and Merchants Bank and hustle into a V-8 Ford that squeals around the corner as cops give chase. It’s 30 seconds of action at most. More than 200 people flank the street across from the bank for the culmination of the 2019 Bonnie & Clyde Days festival. On this blue-sky October day, they are blissfully unaware that such a feel-good community gathering will itself turn outlaw less than six months later, with the pandemic squashing this year’s event.

I’m a city girl who grew up in Dallas with her eyes on bigger-better towns, but I spent that afternoon charmed by the easy camaraderie of Pilot Point, population 3,865. I marveled at the soapbox derby and pie-eating contest, details of small-town life I’d only seen in movies. The mythmaking power of the silver screen was and is at the heart of the festival. The posters made clear this was not a celebration of two real-life bandits who left a trail of 13 dead, but rather “The day Hollywood came to town.”

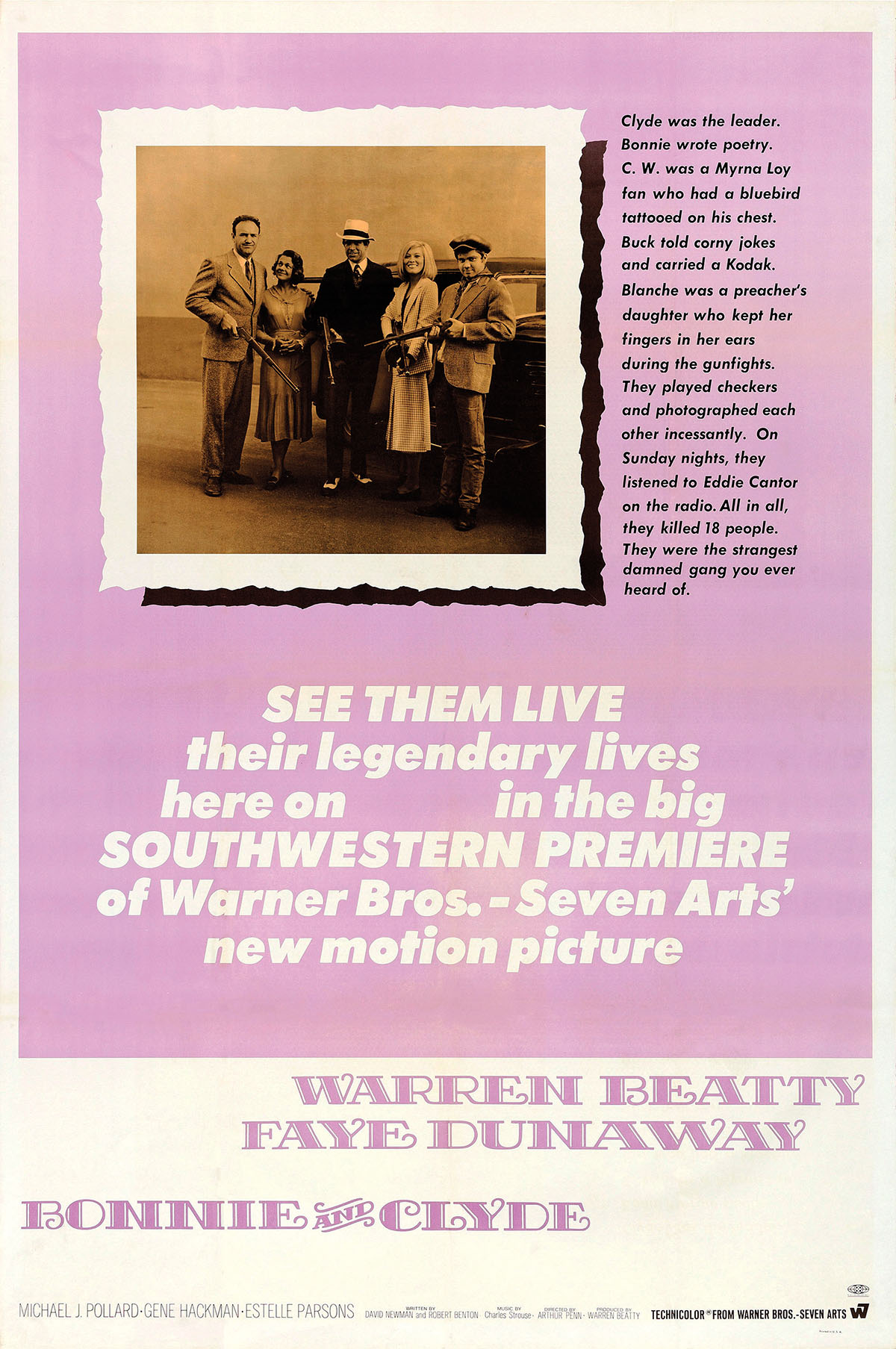

Pilot Point is known for high school football and cabinet making—“It’s like the capital of cabinets in North Texas,” the mayor told me. That a movie as fabled as Bonnie and Clyde was partly filmed here, that stars as iconic as Warren Beatty and Faye Dunaway walked these avenues—well, it was an event so singular that children got the day off from school to gather in the town square and watch the filming, much like we were doing a half-century later. Never mind that the movie was so grim and blood-spattered it ushered in a new era of cinematic violence. All that took a back seat to the glittering notion that once upon a time, Hollywood chose Pilot Point.

I drove back home to Dallas, an hour south on Interstate 35, where Bonnie Parker and Clyde Barrow were raised. They fell in love in my city, they slept and dreamed in my city, they fought and cursed and longed for bigger-better lives in my city. But the best way to characterize the relationship between Dallas and its notorious criminal duo would be to say there isn’t one. No museum, no murals, and certainly no festivals commemorate the fact that two dirt-poor kids from the west side grew up to become a Romeo and Juliet for the “public enemy” age. The only official designation is a historical marker near Clyde’s grave, in an Oak Cliff cemetery. But it’s the gravestone’s epitaph, written by Clyde, that tells the truer story. Etched in black granite are the words “Gone but not forgotten.”

If anything, Bonnie and Clyde were smaller than life. She was 4’11” and less than 100 pounds; he was just shy of 5’6” and weighed 125. Clyde’s family came to Dallas after the collapse of the farm they were tenants on in Telico, about 40 miles south, when he was 12. The Barrows were part of a rural migration that transformed cities in the years after the Great War and before the Great Depression. They were so poor, for a period they slept under their wagon on the flood plain of the Trinity River, in a part of town so lawless it was known as the Devil’s Back Porch.

Dallas was a banking and financial center. Its founders designed the city to attract elites and keep out “unsavory” types. But if you stand on the edge of the Trinity, as Clyde doubtlessly did as a young man, what you see are high-rises and skyscrapers—all the wealth and glory that exist on the other side.

Clyde wanted to be a musician. He played guitar and saxophone, but his nimble fingers proved more profitable hot-wiring cars. He’d already been arrested and sent to jail a few times before the day in January 1930 that he walked into a party and met the woman who would die at his side. He was 20; she was 19.

Bonnie Parker was one of the smartest kids in her class at a time when smarts didn’t get a girl far. Her father died when she was 4, and she became a flirtatious, attention-seeking young woman. She was a waitress at a café on Swiss Circle, near the present-day Baylor University Medical Center, but she longed to be famous. She took pictures of herself in Hollywood starlet poses, like the ghost of Instagram Future. Whether her role in this saga is better understood as a lovesick codependent or a tough broad blowing up assumptions about the fairer sex, what’s clear is Bonnie made Clyde a legend. Without her, he’s just another two-bit crook in an era teeming with them. But with her riding shotgun, they make history.

“Bonnie and Clyde were the Kardashians on media steroids,” says Jeff Guinn, the Fort Worth writer whose gripping account of the couple, Go Down Together, rubs the gloss from the saga to find the troubled humans underneath. They became media sensations, whose two-year crime spree through Texas and the Midwest was breathlessly tracked by a news industry eager for eyeballs and a public eager for escapism. Sound familiar?

Pictures of the outlaws had been discovered by the cops and published in the papers. The shocking, deeply unladylike photos of Bonnie in a beret—variously poking the barrel of a shotgun into Clyde’s stomach and chomping on a cigar—scandalized the masses. A woman! In reality, Bonnie never smoked cigars, and she only shot a gun twice, once by accident and once during a botched holdup when she deliberately fired to miss because she didn’t want to hurt anyone. “It’s possible she killed a pig in the road,” Guinn tells me. But the self-mythologizing images helped turn the couple into folk heroes. This was at a time when plenty of desperate people would have enjoyed sticking it to the man.

As the body count escalated, however, public sympathy dwindled. Thirteen people had died, mostly trying to stop them, by the morning of May 23, 1934, when officers set an ambush off the side of a highway in Gibsland, Louisiana. Led by Texas Ranger Frank Hamer, the posse—dramatized in the 2019 Netflix movie The Highwaymen—fired some 150 rounds into the shiny V-8 Ford. Clyde was 24 when he died; Bonnie was 23. But their story was just beginning.

They fell in love in Dallas, they slept and dreamed in Dallas, they fought and cursed and longed for bigger-better lives in Dallas. But the best way to characterize the relationship between Dallas and its notorious criminal duo would be to say there isn’t one.

At the 2019 Bonnie & Clyde Days festival, actors recreate a bank robbery scene from the 1967 movie filmed in Pilot Point. Photo by Michael Amador.

Actors pose as Clyde and Bonnie at Bonnie & Clyde Days in 2019. Photo by Michael Amador.

Whether Bonnie’s role in this saga is better understood as a lovesick codependent or a tough broad blowing up assumptions about the fairer sex, what’s clear is that Bonnie made Clyde a legend. Without her, he’s just another two-bit crook in an era teeming with them.

“‘Clyde and Bonnie’ just sounds like a Midwest Christian couple who owns a Chick-fil-A,” quipped one of the hosts of Last Podcast on the Left, a participant in the expansive true-crime podcast genre. For a modern audience drawn to tales of complicated women, Bonnie would have to take top billing.

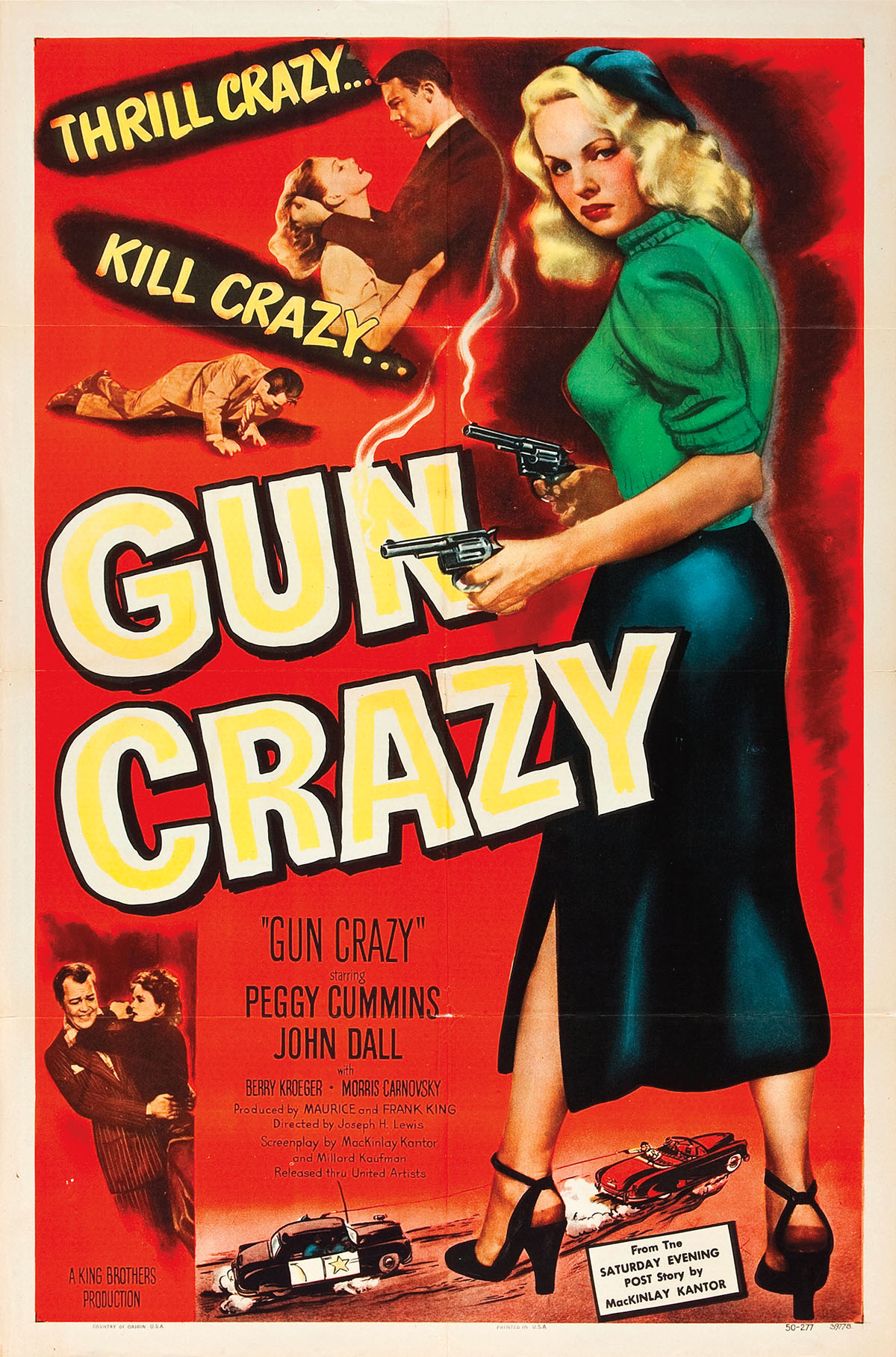

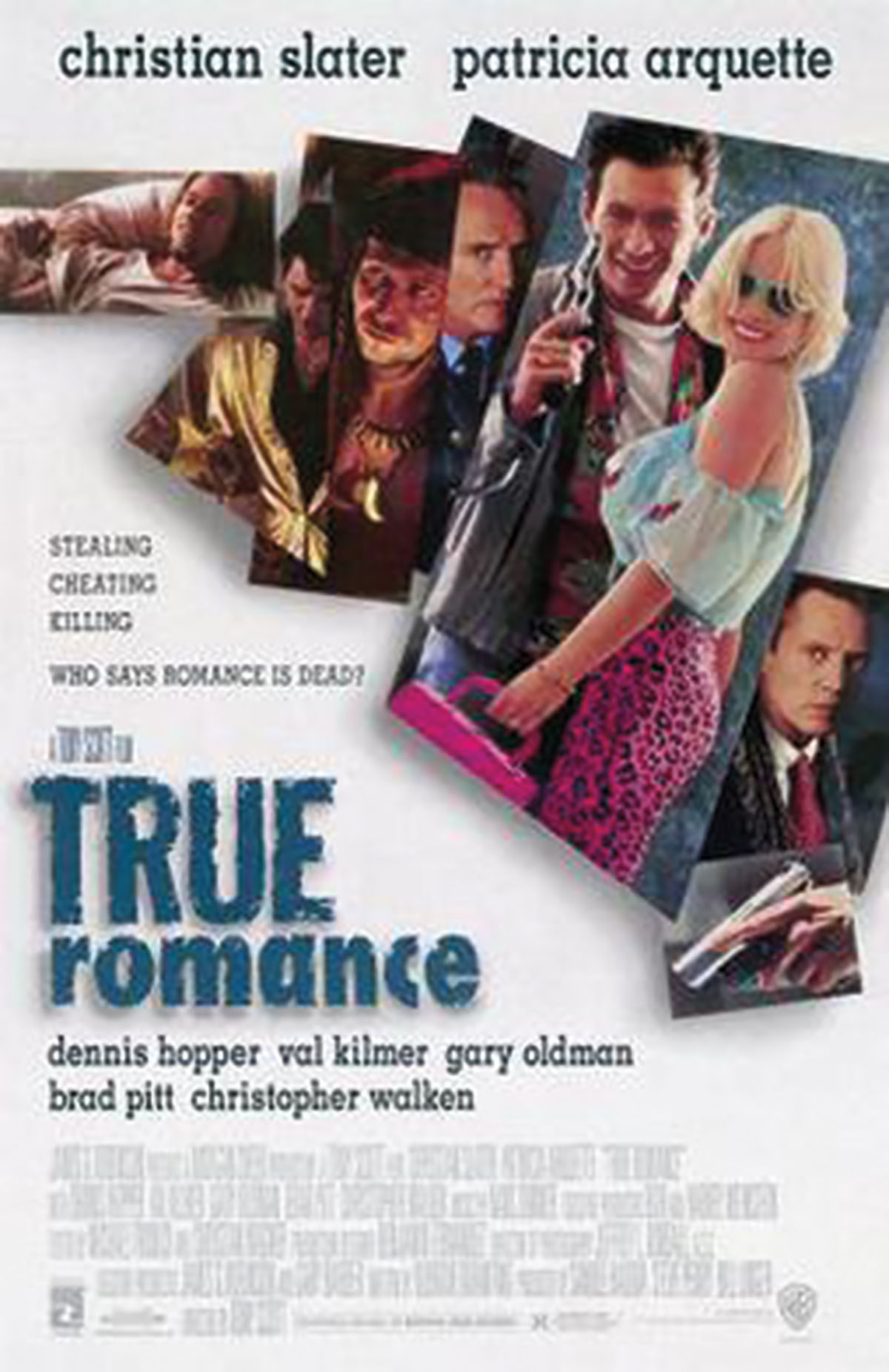

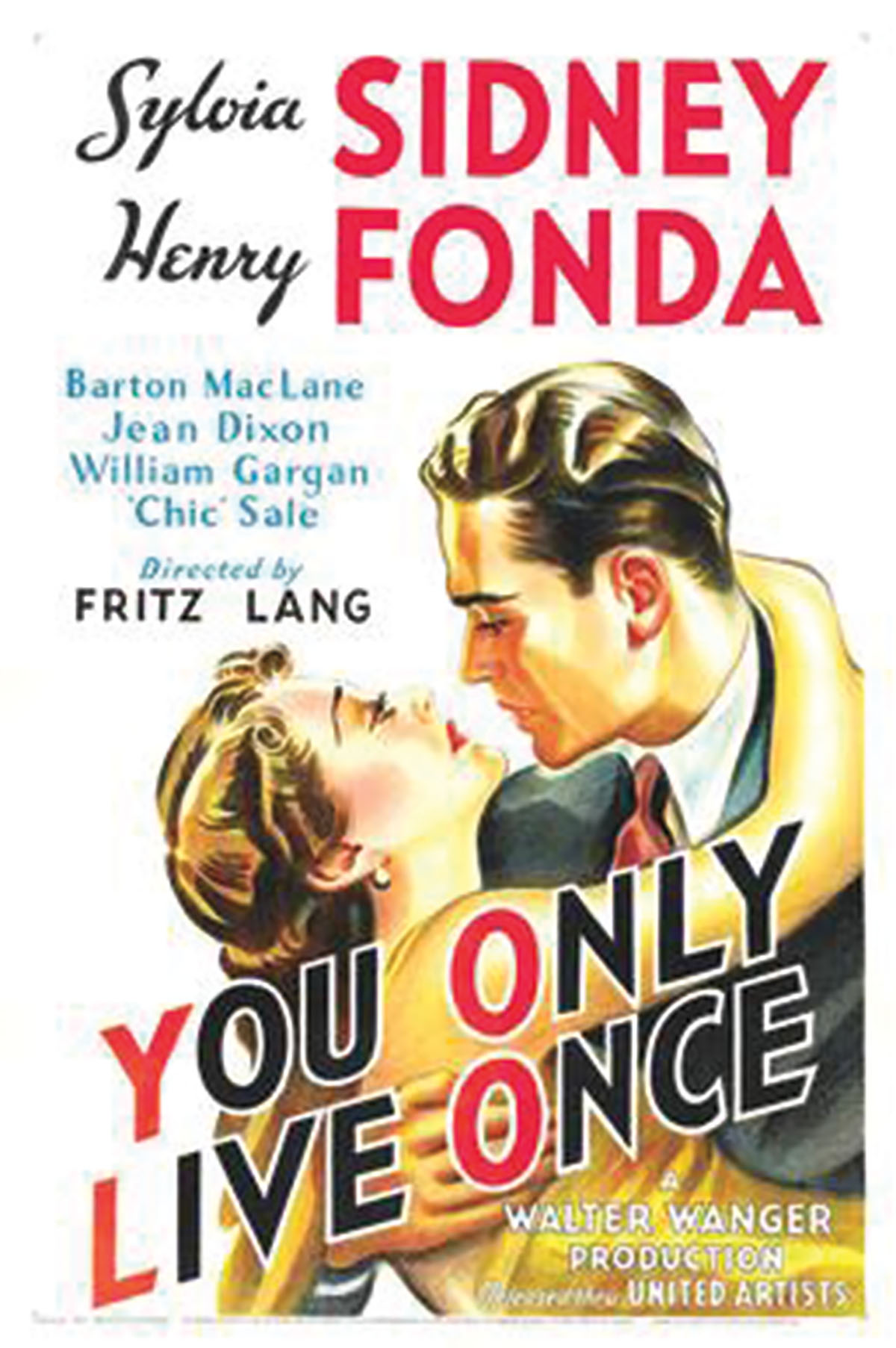

The pulp novels of the ’40s and ’50s recast Bonnie as the leader of the gang, taking their cue from the femme fatales in the hard-boiled fiction of Dashiell Hammett. True-crime magazines portrayed Bonnie as a “Killer in Skirts,” or “90 pounds straight out of hell.” The Bonnie Parker Story hit screens in 1958, with a poster featuring a blond woman dangling a cigar from her lips as she fires a Tommy gun. The mostly forgotten movie was beloved by Quentin Tarantino, who also riffed on the Bonnie and Clyde myth with his screenplays True Romance and Natural Born Killers.

But it’s the stylish 1967 Arthur Penn movie—the Pilot Point one—that brands the couple into the late 20th-century imagination. Filmed all around North Texas and co-written by Waxahachie native Robert Benton, the movie’s gleeful nihilism struck a chord with a counterculture audience, and the names Bonnie and Clyde became synonymous with dark glamour.

In the ’90s, rapper Tupac Shakur name- checked the duo in “Me and My Girlfriend,” a love song to his gun released after he was shot dead in a car in 1996. A year later, Eminem rapped about killing his ex-wife and dumping her body in a lake in the song “’97 Bonnie & Clyde,” originally released as “Just the Two of Us.” Jay-Z and Beyoncé put a sunnier spin on things with “’03 Bonnie & Clyde,” a bling-era anthem that drops references to Birkin bags and Burberry. This image of a ride-or-die couple uniting not to rob banks but to take on the world is so winning that it’s not unusual to see a man on a dating site saying he’s “looking for his Bonnie.” Earlier this year, as if to prove the Bonnie and Clyde mythology has been so thoroughly metabolized it hardly means anything, the names were slapped on memes of a middle-aged white couple who pulled guns on Black Lives Matter protestors in an affluent gated community in St. Louis.

What’s remarkable about how large Bonnie and Clyde loom in the public consciousness is how whisper-quiet their presence is in Dallas, the city that shaped them. My house is about two miles from the café where Bonnie poured coffee, a vacant crescent-shaped building that I must have passed 100 times without knowing its history. The service station where the Barrow family once lived stands on the corner of Singleton Boulevard and Borger Street. The derelict brown building with boarded windows and white graffiti is just over a mile away from the $182 million Margaret Hunt Hill Bridge and the Trinity Groves strip of restaurants, which have helped transform the forgotten part of town once known as the Devil’s Back Porch into a spot for top-shelf margaritas and killer guacamole.

“This city hides from its past like we owe it money,” wrote Robert Wilonsky, in a Dallas Morning News story about the battle over the fate of the Barrow gas station as well as an abandoned building around the corner known as the McBride house, where Clyde killed an officer in a 1933 ambush. Both have become points of contention in a rapidly developing neighborhood. Whether these ramshackle structures are blights in need of destruction or artifacts in need of preservation depends on whom you ask. History, like all stories, is a very complicated bargain.

Bonnie & Clyde’s Hideout is named for its proximity to a secret spot where the couple used to meet family members while they were eluding the law. I admired archival photos and old news clippings on the walls as men drank alone at tables watching the game. I was hit with a wave of tenderness for whoever had curated this collection. This was not some soulless hotel sports bar, as I had mistakenly imagined, but a place that connected me to the real people who had passed through, who had fought themselves and their own histories, who struggled to get away and then to get back. But it’s hard to strike the right balance between knowing history and glorifying it. Not too far from that bar, off State Highway 114 in neighboring Southlake, you can find a modest memorial to the officers who lost their lives after a run-in with the duo in 1934. Those men were real, too.

“It’s a quirky little festival,” Mayor Shea Dane Patterson says of the event she helped create. She was disappointed, too, but what can you do? The festival is a break-even affair, but the joy was in the gathering. What the real Bonnie and Clyde had in common with the people of Pilot Point, and with me, and with most of us, is that they wanted to be connected to something greater than themselves. Their story is a cautionary tale about a lust for fame and the tragic allure of crime, but it’s also about small people who wanted to be bigger.

Patterson told me some folks don’t like the idea of celebrating criminals, but that’s why she reminds everyone this is about the movie. The actual Bonnie and Clyde never robbed the Farmers and Merchants Bank in Pilot Point anyway, though there’s a rumor they were once seen in the town square. “It’s believed the reason they never robbed it was they had family in the area,” Patterson says, but like so much of their story, no one knows for sure.

What the real Bonnie and Clyde have in common with the people of Pilot Point, and with me, and with most of us, is that they wanted to be connected to something greater than themselves.