There’s nothing like the feeling of stepping onto Willie Nelson’s tour bus. Whether you do it once or a hundred times, it’s a thrill to be invited onto Willie’s rolling roadshow. Stories will be told. New songs may be played. Jokes that may or may not be suitable for print will be exchanged. And laughter will definitely ensue.

It’s Saturday night in the Fort Worth Stockyards. A sold- out crowd is already finding their seats just a few steps from Willie’s bus, which is parked behind the world’s largest honky tonk, Billy Bob’s Texas. I’ve come to see an old friend and to hear what might be my 100th Willie concert. Or maybe my 300th—I lost count long ago.

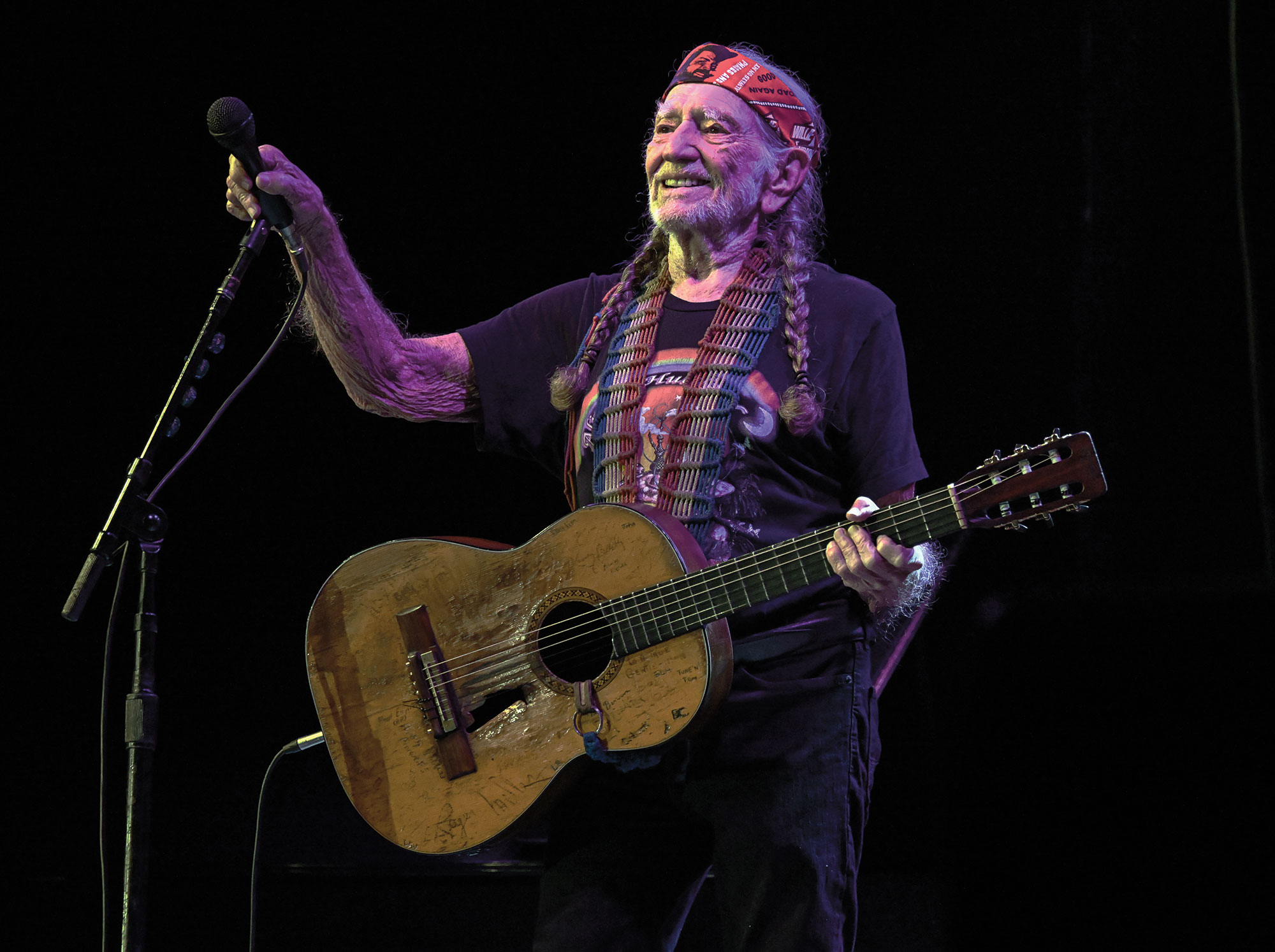

I first met Willie 40 years ago at the door of his bus, though that was about five buses previous. I was his opening act at Auditorium Shores in Austin, and when I left the stage, the promoter told me to go back in front of a rowdy crowd and tell them their headliner might be delayed. Ten thousand strong, they were chanting Willie’s name, and I was afraid to face them again, so I went to the bus and knocked on the door. Willie opened it wide, already a Texas legend and one of the biggest acts in America—his braided ponytails held in place by his trademark bandana.

“They’re ready for you, sir,” I told him. He gave me a big grin, and said, “Let’s go.”

Though the buses have grown more refined over the decades, they haven’t changed much, and neither has Willie. Soon to turn 86 years old, his braids remain long and strong, and his enthusiasm for entertaining a crowd hasn’t waned. Willie and the bus are still together for more than 100 days a year. He feels at home on the bus and knows that the tour’s three lead drivers, with 100 years of experience between them, will get him safely down the road from one show to the next.

Willie’s and my paths don’t cross as much as they used to, so it feels good when he stands and gives me a hug and a smile.

“How you doing?” Willie asks. “Are we working or having fun?”

“Both,” I tell him. He laughs. And that’s a good start for an interview, especially one with an old friend.

I’ve just arrived from Austin and tell Willie I stopped in his hometown of Abbott, which doesn’t seem to have changed much since he was a skinny red-haired kid nicknamed Booger Red.

“You have two new Grammy nominations,” I say. “You’ve recorded a hundred studio albums, and you’re still recording and touring hard. You’ve come a long ways from Abbott.”

“Yep,” Willie says with a smile. “About 60 miles!”

We both laugh. It’s a good line, partially because he really has come far, even while staying true to who he was before the awards and adoring crowds.

I tell him I checked out the Methodist Church that he and his sister, Bobbie, rescued, and the West Volunteer Fire Department’s new firetrucks that Willie’s Fourth of July Picnic funded after the West fertilizer plant explosion. I even swung by the Hill County Courthouse, rebuilt after a fire with the proceeds of a Willie Nelson concert, then rededicated with another Willie show on the town square.

“Abbott and Hill County are where I grew up,” Willie reminds me. “I had a lot of fun there. And a lot of friends. I still do.”

Willie still plays poker and dominoes with some of those friends, and I can testify firsthand that you can get your pockets cleaned in those games. I’m fairly good around a gaming table, good enough to recognize how great Willie is at poker, chess, checkers, and dominoes

“Which game are you the best at?” I ask.

“Dominoes. By far,” he says immediately. “When I was young, a lot of old men from Abbott sat around playing dominoes every day, and when they got up for a break, they’d set me down in their spot. If I messed up, they’d really chew my ass out!”

Willie’s wife, Annie, seated on one of the bus’ sofas, joins in on the laughs. Annie has been his dedicated companion and partner since they met while shooting a Western movie in the ’80s. Willie’s parallel career in movies has had a focus on Westerns, and from early classics like Red Headed Stranger and Barbarosa, it was clear Willie really knew his way around a horse.

“Did you ride horses when you were a kid?” I ask.

“I have a picture of me about 2 years old riding a milk cow,” he says. “I’d ride anything that would stand still long enough for me to jump on it. One time when I was really young and dumb, I was riding this calf, and I thought if I tied my hands and feet together, he can’t throw me off. Wrong. He dragged me around town for a while!”

Willie and Annie once rescued a herd of American paint horses who were destined for a slaughterhouse. The idea was to save their lives, then find them new homes, but I’ve noticed that many of those beautiful black and white paints are still living happily at the Nelsons’ ranch and Western movie town outside of Austin, a place Willie calls Luck, Texas.

“If you’re not here,” he likes to say, “you’re out of Luck!”

I mention that I’d seen the couple’s son, Lukas, play a couple of nights before. Lukas and his band Promise of the Real had one of the best albums of 2018, and Lukas played Bradley Cooper’s bandleader in the Oscar-nominated movie A Star is Born. What you don’t see on screen is that Lukas also taught Cooper how to sing, played Cooper’s guitar parts, and wrote or co-wrote seven songs in the movie, some with Lady Gaga. When he’s not touring with his own band or Willie, Lukas and his brother, Micah, are front and center for Neil Young’s tours. “The best band I’ve ever had,” says Neil, which is saying a lot.

“I know you’re proud of those boys,” I tell Willie.

“I’m lucky enough to have family that also plays music, and they’re all pretty good,” Willie says. “It’s about as good as it gets when you get your kids up on stage with you and you can be proud of them at the same time.”

Having seen the patience with which Willie teaches a guitar lick to one of his kids, I point out that the kids are not good by luck; they learned a lot from their dad.

“I inherited a lot of my talent,” Willie says modestly. “I’m sure they did, too.”

For Willie, getting to hear their music and play with his boys, and with his daughters, Amy and Paula, is better than taking credit.

The results of their joint creations are often spectacular. Nashville’s Buddy Cannon, who produced the album Willie & the Boys with Willie, Lukas, and Micah, remarked that sometimes their harmonies are so perfect they sound like one voice.

Click the image above to view the slideshow.

Wanting to see Willie’s entrance, I make my way inside Billy Bob’s, an enormous night club with the best seats at long picnic tables stretching out from the stage and additional viewing tiers stretching to the back bars. Surveying the crowd, I see plenty of families spanning from teenagers to great grandparents. Going to a Willie concert is a family affair.

When the stage lights dim, Willie walks out to cheers and a standing ovation, and launches straight into “Whiskey River,” which brings an even louder roar from the crowd. The mood is electric, and Willie barely pauses between songs on a 90-minute set of hit after hit. His Family band is smaller than in the old days—the passing of guitarist Jody Payne and bassist Bee Spears in 2013 and 2011, respectively, were deep-felt losses, but Willie was able to move forward with a smaller group that’s as tight as ever. Willie’s sister, Bobbie Nelson, then a few months shy of her 88th birthday, wows the crowd on every piano solo.

“He wears a lot of hats: mentor, guitar god, friend, father figure.”

Consider this: Willie and Bobbie have been playing together for eight decades, with hardly a break since the 1970s, and she is as much a part of Willie’s live sound as his famous acoustic guitar, Trigger, or Mickey Raphael’s distinctive harmonica.

Mickey, who began playing harmonica for Willie at 22, is a perfect example of why everyone in the group is called “family.”

“Willie is the same guy now as when I first started in 1973,” Mickey tells me.

“And who is that?” I ask.

“He wears a lot of hats: mentor, guitar god, friend, father figure,” Mickey says. “That all means he’s just Willie.”

The show moves at a rapid pace. Willie doesn’t stop to chat and only takes enough time between songs to kick things into the next gear.

Taking off his straw cowboy hat, Willie spins it dexterously into the audience, sailing it 20 feet deep and bringing another big cheer. A few minutes later I walk past the guy who caught it, and he’s holding the hat in his hand like a holy relic, a look on his face like he’s achieved nirvana. And in a way, I guess he has.

Willie once told me that if an audience is slow to warm up, he likes to win them over one by one. Watch close and you’ll see him looking people in the eye, giving each one a tiny smile, a wink, a nod. I’ve had more people than I can count tell me that Willie singled them out with some special recognition during a show.

How many winks and how many waves, I wonder. How many hats and bandanas? How many $100 tips in some roadside cafe?

A few years back, I was Willie’s co-author on a best-selling book called The Tao of Willie (or the “Toe of Willie” as he liked to pronounce it). For a year or two after the book was published, strangers would tell me their stories of how Willie’s generosity saved the day for them at some low point in their lives. Those recipients all became lifelong Willie fans, buying albums and going to shows for years to come, so the generosity seems to have worked for everyone involved.

The show flies by—one for Waylon, two for Hank, then “Bloody Mary Morning” for the fans who’ve been with him since 1974 when he turned country music upside down with his album Phases and Stages, a cycle of concept songs that tell a husband and wife’s contrasting perspectives of divorce. With that album and Red Headed Stranger following in 1975, Willie changed country music from three chords and a tired suit to a world that had room for artists like Townes Van Zandt and Charley Pride.

Click the image above to view the slideshow.

In the ’70s, Willie basically integrated country music clubs in Texas and Louisiana by hiring Charley Pride as his opening act. One night at the Longhorn Ballroom in Dallas, Willie introduced Charley to an audience whose applause fell quiet when a black man walked to the mic. Going back on stage, Willie kissed Charley right on the lips. “That shut ‘em up,” Willie told me. “And they loved his music.”

Charley was soon one of the biggest acts in country music, ultimately garnering 29 No. 1 country hits. He calls his tours with Willie “a watershed” in his career. Still friends with Willie, he came from his home in Dallas to say hi and see the show at Billy Bob’s.

Charley’s admiration for Willie is seconded by just about every other musician in Texas. When Willie moved back to Texas from Nashville in the early ’70s, his shows at Armadillo World Headquarters, Willie’s Fourth of July Picnics, and almost everywhere he played had two audiences: rednecks and hippies—two groups that didn’t get along.

“They all got together and listened to music, drank a little beer, and did other things,” Willie says, “and they realized they didn’t hate each other after all.”

“Are we divided like that again in America?” I ask him.

“Not as much as people think,” Willie tells me.

Click the image above to view the slideshow.

Offstage, Willie has never been shy about politics. He’s dedicated a fair amount of his life to Farm Aid’s support of America’s family farmers; he’s supported Native American causes, and has had friendships with a number of governors and presidents, going all the way back to Jimmy Carter. But you won’t hear any of that at his shows.

“We don’t do politics during the show,” Willie reminds me. “The people come to hear my music. And that’s what we do.”

Willie has slowly cut down from 200 shows a year to closer to 100, which is still more than most acts half his age. Lots of big names command huge ticket prices by playing only a few shows a year, but if you want to play for lots of fans all over the country, then you just keep going “On The Road Again” (an anthem Willie wrote in five minutes on an airplane barf bag after producer Sydney Pollack suggested their movie Honeysuckle Rose needed a song about life on the road).

Two nights after the Billy Bob’s show, Willie was playing one of the bigger shows of his year, a taping of Austin City Limits, the longest-

running music show in television history. Guess who was the star performer at that first taping 44 years ago? Now he’s back, playing in The Moody Theater that was built on his legend.

There was an excited crowd for the ACL taping, but when Willie came onstage it was cold in the theatre, and he was wearing a jacket. For a song or two, his voice wasn’t as strong as at Billy Bob’s. But I still saw him looking into the crowd from person to person, and before long, he was warmed up, taking off the jacket, and singing in full Willie form. The crowd knew it too, and their spirits rose with him.

His guitar solos on “Night Life” are always incredible, but at ACL his hands seemed to find some new inspiration; likewise for his playing on “Angel Flying Too Close the Ground” and Django Reinhart’s jazz classic, “Nuages.”

The audience knew they were seeing something special. In a way, they all seemed to have that same look of joy as the guy at Billy Bob’s who caught Willie’s hat. It was, without a doubt, a room filled with love. When the house lights came on the crowd filtered out, but a couple in front of me stood together holding hands for a long while, watching the spot where Willie walked offstage, not wanting to let the moment go.

Willie Nelson is defined by music and by time—both his decades-spanning career and his ability to make the most of every moment. And he is defined by love, not just love for his family or his fans, but by the universal concept—that living from one’s heart is the best use of our lives.

It’s almost impossible to imagine a world without Willie Nelson. Despite the frequent internet rumors that his health is failing, Willie shows no signs of surrendering to time. Instead, he responds with a funny song like “Still Not Dead Again Today.” Those lyrics are now an anthem all their own: “I woke up still not dead again today. The news said I was gone to my dismay. Don’t bury me, I’ve got a show to play.”

Not long after New Year’s, I found myself in Luck, literally, where Willie signed a Martin guitar for my wife’s birthday (after playing “Nuages” on it to make sure it was a good one). Then he took out his phone and played recordings of five incredible new songs for us, three of which he’d written in the last week.

“Willie still plays 100 shows a year, more than most acts half his age.”

“When do you write all these songs?” I asked.

“In my dreams,” he said. We laughed, but I don’t think he was kidding.

My favorite of the new songs is called “Come on Time.” Co-written with Buddy Cannon, who is producing his 13th album with Willie, the song sets Willie’s conversation with time to a gentle waltz tempo.

“Time,” Willie sings in a voice still strong but also clearly marked by its passage. “As you pass me by. Why did you put these lines on my face? You sure have put me in my place. Come on time. Looks like you’re winning the race.”

The song was so beautiful, I was practically in tears. After the last notes played, we sat there quietly for a long while. It was time for me to leave, but I didn’t want to go.