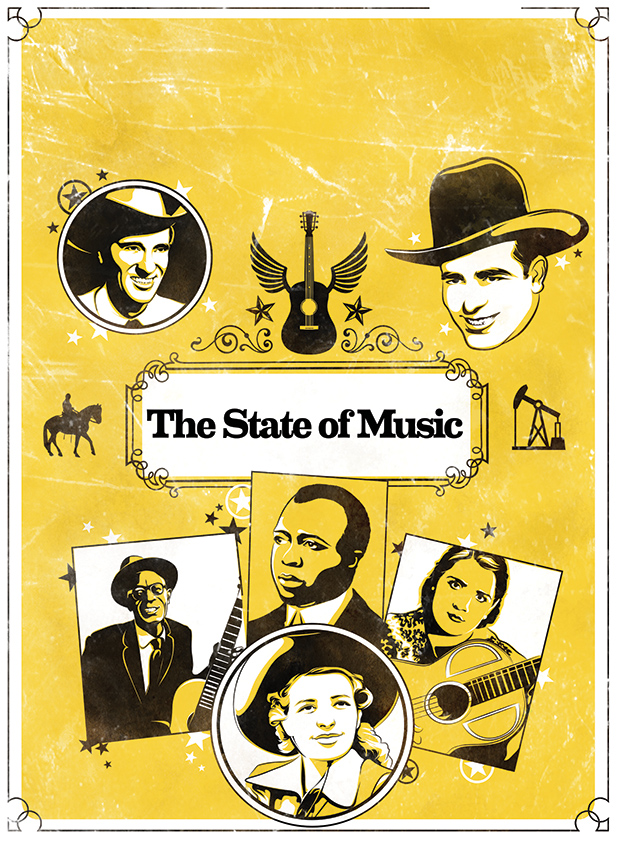

(Illustration by Aaron Sacco)

No state is more musical than Texas, whose very geography seems to hum. Even the city names remind you of songs. It’s easy to break into a medley of “San Antonio Rose,” “El Paso,” “Streets Of Laredo,” “Amarillo By Morning,” “Galveston,” and “La Grange” while checking out the ol’ Texas road map.

Texas Music Read

The University of North Texas Press is set to release Michael Corcoran’s All Over the Map: True Heroes of Texas Music, which profiles more than 40 Texas music pioneers, in May 2017.

Read more Texas Highways articles by Michael Corcoran.

Texas Music Museums

Texas is home to numerous music museums highlighting the state’s musical pioneers with displays of photos, instruments, albums, and other memorabilia.

Texas Musicians Museum, Irving

Texas Polka Music Museum, Schulenburg

Texas Music Museum, Austin

Bullock Texas State History Museum, Austin

Museum of the Gulf Coast, including the Music Hall of Fame, Port Arthur

Texas Country Music Hall of Fame and Tex Ritter Museum, Carthage

Heart of Texas Country Music Museum, Brady

Selena Museum, Corpus Christi

Buddy Holly Center, Lubbock

Roy Orbison Museum, Wink. 432/527-3743.

Lefty Frizzell Museum, Corsicana

Bob Wills Museum, Turkey. 806/423-1033.

Freddy Fender Museum, San Benito

Musical pioneers come from every corner of Texas, all of them contributing to and drawing from a stew that mixes flavors from a diversity of landscapes, cultures, and lifestyles. Black-and-white cowboy movies, popular with all races and ages, gave Texans a lot to live up to, and they inspired music with just a little more swagger. The mythical Texas we love—stoked by big hair, big cars, and bold proclamations—has been made real by musical pioneers.

Some towns remind you of the great musicians who couldn’t wait to get out. Beaumont conjures a 12-year-old George Jones singing on the street for tips, and it’s impos-sible to see Wink on a map without imagining Roy Orbison slipping on his first pair of dark shades. Centerville?

That’s the birthplace of gritty blues giant Sam “Lightnin’” Hopkins. Baytown gave the world Chitlin’ Circuit kingpin Joe Tex, a virtuoso of the mic stand.

Certain burgs are associated with the greats who never left. Little Joe Hernandez still calls Temple home; Navasota is where Mance Lipscomb lived and died; Adolph Hofner stayed around San Antonio, blending the polka of his Czech and German ancestors with Western Swing; while Jimmy Heap and the Melody Masters made history in Taylor with the 1951 original version of “Wild Side of Life.”

The wide-open spaces of rural Texas have inspired the best Lone Star songwriters—from Willie Nelson to Cindy Walker and Townes Van Zandt—to add to the meaning and power of their songs by leaving out any clutter.

Texas is a state of immigrants, with a geography as diverse as its people. It was the first U.S. state to have sizable populations of both African Americans and Mexican Americans—and both cultures made a huge imprint on the music.

Mexicans brought Spanish guitars to the picking fields, the Czechs and Germans brought accordions to their dance halls, and the sons and daughters of slaves brought the rhythm that screamed to be free. Texas is where blacks played country, farm boys played big band jazz, and everyone played the blues.

A Texan was the first to record a country tune (Amarillo’s Eck Robertson in 1922), the first to play an amplified guitar on record (Eddie Durham of San Marcos in 1935), and the first to explore “free jazz,” as Fort Worth alto sax player Ornette Coleman’s idiosyncratic experimentations were dubbed in the late ’50s.

The original national recording stars of guitar blues and country were Texans. Blind Lemon Jefferson of the Wortham area recorded nearly 80 country blues tunes for Paramount Records. Jefferson’s Vernon Dalhart, who supposedly took his name from two Texas towns he visited in his youth, was the first country singer to sell a million records with “The Prisoner’s Song” backed with “The Wreck of the Old ’97” in 1924.

Lubbock’s Buddy Holly and the Crickets were the first rock combo to write and produce their own hits, helping to inspire the British Invasion a few years later. (The Beatles’ name was an homage to the Crickets). Ernest Tubb and the Texas Troubadours took the honky-tonk sound nationwide with “Walkin’ the Floor Over You” in 1941. The country’s first electric blues guitar hero was T-Bone Walker of Oak Cliff; its first great electric jazz guitarist was Bonham native Charlie Christian.

In the gospel field, a trinity of Texans—Blind Willie Johnson, Washington Phillips, and Arizona Dranes—were putting religious lyrics to hot piano and guitar in the 1920s. And while the Soul Stirrers are best known today as Sam Cooke’s gospel group, it was while fronted by Rebert Harris in Houston in the ’30s that the Stirrers perfected the “hard gospel” quartet style that led to soul music.

Both boogie-woogie piano, originally known as the “Fast Western” style for the Texas Western railroad that ran through Marshall, and “psychedelic” rock originated in the Lone Star State. George W. and Hersal Thomas, the brothers of Houston-raised blues great Sippie Wallace, first put boogie woogie to sheet music in the early ’20s, while Austin’s 13th Floor Elevators were making acid rock back when LSD was still legal.

Would jazz have gone where it did when it did without Dallas sax players Henry “Buster” Smith and Budd Johnson? Smith played in the Kansas City Blue Devils in the late 1920s and early ’30s with a protégé named Charlie Parker. Johnson played with sax giant Coleman Hawkins in 1944 on a session credited as the recorded birth of bebop. And while New Orleans is rightfully designated the birthplace of jazz, there’s no denying that Scott Joplin of Texarkana provided the template with his syncopated ragtime compositions in the late 1890s.

Texas is where music is made for dancing. Historically, rowdy, exuberant crowds coaxed musicians to play louder, first out of necessity and later because the added power expanded the boundaries of the music’s sound and configuration. The size of dance halls required bands to feature more players, with Milton Brown of Fort Worth adding twin fiddles and piano to his Musical Brownies. His fellow Western Swing inventor Bob Wills upped the danceability with drums and electric guitar.

Money, oil, independence, and big noise: That’s Texas, a land of opportunity within the land of opportunity. It’s where the South ends and the West begins, and yet Texas remains independent of those regions. Of course, Texas is not the only state with impressive musical heroes.

Mississippi, Louisiana, Tennessee, California, and many more states can boast of the music they’ve given the world. But Texas stands out for its sheer number of musical pioneers, spanning several genres.

In the Latin music field, the late Lydia Mendoza, who made her career in San Antonio, had a smash in 1934 with the ballad “Mal Hombre,” while the first person to have a national Cajun music hit was Harry Choates of Port Arthur with “Jole Blon” in 1946. DJ Screw of Smithville showed the rest of the rap world how to slow it down in the ’90s, the same decade Selena took Tejano music to the top of the pop charts.

The range of Texas music is spectacular: It seems that for every national superstar like Ray Charles or Merle Haggard, there were Texans like blues/jazz pianist Charles Brown of Texas City or country crooner Lefty Frizzell of Corsicana who showed them the way.

And with Houston native Beyoncé Knowles reigning as the current queen of pop, the Lone Star State continues to shine in the musical galaxy. Like football, music has mattered here forever, going from pastime to tradition. Born as a diversion, then growing up to be a livelihood, music is a way of life in Texas, where the frontier mentality rewards those who go just a little farther.