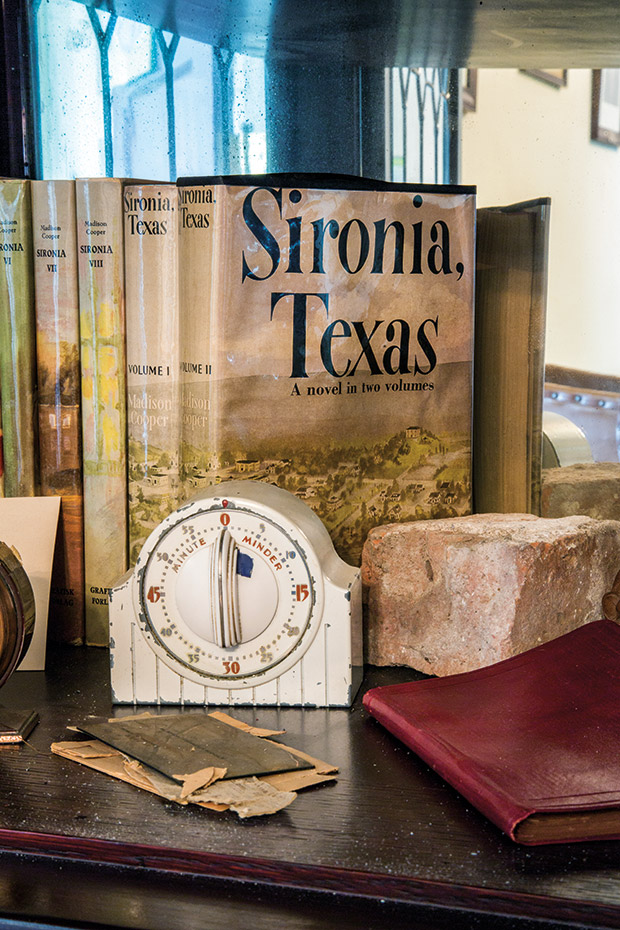

The Houghton Mifflin Company made history in 1952 with the publication of a novel called Sironia, Texas. At 840,000 words, the book’s two volumes made up what was believed to be the longest novel in the English language at the time, dwarfing both Gone with the Wind (500,000 words) and War and Peace (670,000 words).

The Cooper Foundation offers tours of the Cooper House, located at 1801 Austin Ave., by appointment. Call 254/754-0315.

More on Madison Cooper Jr.

Learn more about Madison Cooper Jr. in the biography Madison Cooper, written by Marion Travis and published by Word Inc. in 1971. Madison Cooper Jr. is buried in the Cooper family plat at Oakwood Cemetery in Waco—Block 8, Lot 25—marked by a large granite cross and a marble angel. The cemetery is at 2124 S. 5th St. in Waco. Call 254/754-1631.

Sironia and its multigenerational tale of early 20th-Century Southern aristocracy made a national stir as a New York Times bestseller and winner of the Houghton Mifflin Literary Fellowship Award. But nowhere did the novel garner as much attention as in Waco, the hometown of the book’s reclusive author, Madison Cooper Jr., who had written the entire 1,731 pages in secret.

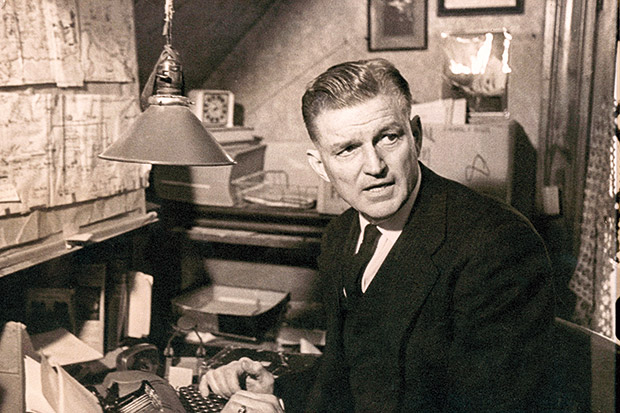

Born into a prominent Waco family in 1894, Cooper attended high school in Waco and graduated from the University of Texas at Austin with an English degree before serving as an infantry captain in World War I. After the war, he returned to Waco to work in his father’s wholesale grocery business. His office was a cramped, low-ceilinged compartment on the third floor of his parents’ home on Waco’s privileged Austin Avenue.

Now the home of the Cooper Foundation, the 1907 Cooper House is open for tours by appointment. Madison Cooper Sr. and his wife Martha Roane Cooper spared no expense when they built the stately mansion with Corinthian columns, leaded glass windows, and a wrap-around porch as wide as a country lane. Immaculately restored in 1985 and listed in the National Register of Historic Places, the house has molded ceilings, period furniture, and oak pocket doors that reflect early 20th-Century Southern elegance.

Pictures and artifacts throughout the house give visitors a glimpse of a half-century of Cooper family life. Photos of Madison Sr. and Martha adorn the stairwell, and a portrait of Madison Jr. in his World War I uniform sits on a small table. In an upstairs room, a framed print by William Barss, who contributed illustrations to Sironia, depicts the fictional Texas town. Best of all, the attic office where Cooper Jr. wrote the book is just as he left it. An open checkbook sits on the battered table he used for a desk. A faded 1956 calendar hangs on the wall next to a rusty pea-green filing cabinet.

It’s this dusty, claustrophobic, third-floor cubicle that draws the attention of most anyone who has ever dreamed of writing the great American novel. Alone in his office, Cooper began writing Sironia, Texas in 1941. He wrote secretly, between appointments, managing various business enterprises while writing the world’s longest novel.

Cooper pulled off such a feat because he was a man of precise habits, living by a strict schedule of work, exercise, and relaxation. He timed his appointments—the kitchen timer is now displayed in a second-floor office of the Cooper House—and when the timer went off, the meeting was over. He only answered the phone between 8 and 11 in the morning. He turned out the lights every night at five minutes to 11 and was asleep on the hour.

Yet Cooper defied easy categorization. The New York Times, covering Cooper’s book in 1952 and his death a few years later, described the lifelong bachelor as a self-proclaimed playboy. And on its website, the Cooper Foundation recounts an inconspicuous figure on the streets of Waco: “Around town, most often on foot, Cooper usually wore baggy khaki pants, an old, plaid flannel shirt, if it were cool, an equally ancient sweater and shoes that had been repaired so many times they were past help. When he was on business, Cooper carried a battered, leather briefcase containing records on rents he needed to collect, business he had to conduct that day and, almost always, a list of books he intended to check out of the library on the way home.”

Cooper’s epic novel describes the decline of the old Southern aristocracy in fictional Sironia and the rise of the merchant class in the first two decades of the 20th Century. The transition was not always smooth or pretty. Sironia had more than its share of murder, mayhem, sex, romance, racism, and haughty behavior. Cooper insisted that Sironia was an imaginary place, but from the day it was published, many Wacoans believed the setting to be a thinly disguised version of their town with characters based on real Waco citizens. Cooper may have based the character Calvin Thaxton on Governor Pat Neff (who also served as Baylor University president) and the Southern Patriots on the Ku Klux Klan, according to an account in The Handbook of Texas. It was once a popular Waco parlor game to guess the characters’ true identities.

Reviews for Sironia, Texas were mixed in the fall of 1952. The Chicago Tribune declared it “something of a masterpiece,” while the Wichita Eagle called it “a simple novel on a sustained, shallow level.” The New York Post rated it “several notches above Gone With The Wind.” But most New York critics blasted it, claiming its notoriety came more from its length than from its artistic quality.

Still, the book was a New York Times bestseller for 11 weeks before fading quickly. A hefty $10 price tag hampered sales. Another problem was timing. The book’s publication coincided with the release of a number of classics, including The Old Man and the Sea by Ernest Hemingway, East of Eden by John Steinbeck, The Caine Mutiny by Herman Wouk, and Giant by Edna Ferber. Few novels could stand up to that kind of competition.

Cooper seemed to take it all in stride. He even published a second novel in 1955. The Haunted Hacienda, at 303 pages, was a short story by Cooper’s standards. Most critics were not kind to The Haunted Hacienda, and sales were disappointing.

Then on September 28, 1956, Madison Cooper left home to run a mile at Waco’s Municipal Stadium as part of his regular exercise routine. When he did not return on time, his housekeeper knew something was wrong. Cooper was never late. He was found slumped over the wheel of his Packard in the stadium parking lot, dead of a heart attack at age 62.

Cooper’s will directed that his literary files be burned, perhaps to shield the friends who inspired his fictional characters, and that all correspondence be destroyed, so as not to embarrass his women friends. He left his entire $3 million estate to the Cooper Foundation with proceeds earmarked for the betterment of Waco. To date the Cooper Foundation has dispersed more than $24 million, including grants to Big Brothers and Big Sisters, the City of Waco Animal Shelter, the Methodist Children’s Home, and the YMCA of Central Texas.