The German group sport of volksmarching brings Texans together for fitness and camaraderie

Susan Medlin (left) and Ellen Ott volksmarch in San Antonio.

U.S. Army lieutenant Susan Medlin was stationed in Augsburg, Germany, in 1984, the year before the Bavarian city’s 2,500th anniversary. As dry, warm winds descend-ed from the Alps, signaling the turn to spring, Medlin knew how she would spend her Saturday mornings: traveling with a group of fellow lieutenants to traditional volksmarching events.

A volksmarch—German for “march of the people”—is a 5K, 10K, or 20K walk designed for people of all ages and fitness levels. Flexible start windows and no finish-time requirements encourage people to walk together rather than compete against one another. Volksmarching allows the group to take pleasure in a shared journey of exploration and discovery.

Medlin and her friends saw the country this way, walking in Munich, Rothenburg ob der Tauber, Stuttgart, Baden-Wurttemberg, and Adelsried. After each walk, there was a celebration: an oompah band, meat sizzling on a grill, and, of course, beer. Though most volksmarches were held in the warmer months, Medlin remembers driving with a friend to a winter walk on a cold December night.

“We were each given a lit torch—reeds bound and dipped in pitch, then set on fire,” Medlin recalls. “I felt very medieval tromping around in a snow-covered field with a lit torch. All we needed was a pitchfork, and we were ready to storm the castle!”

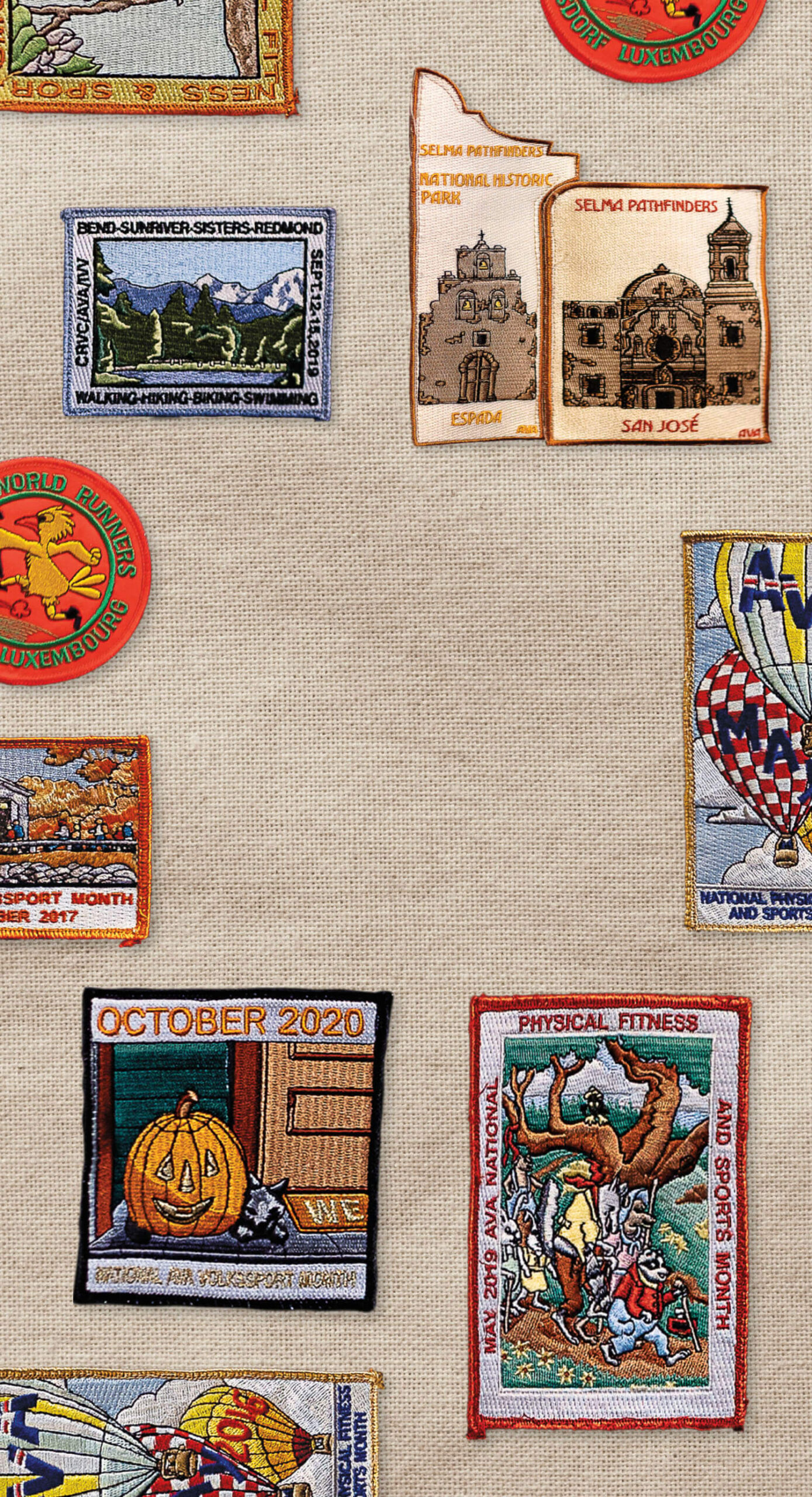

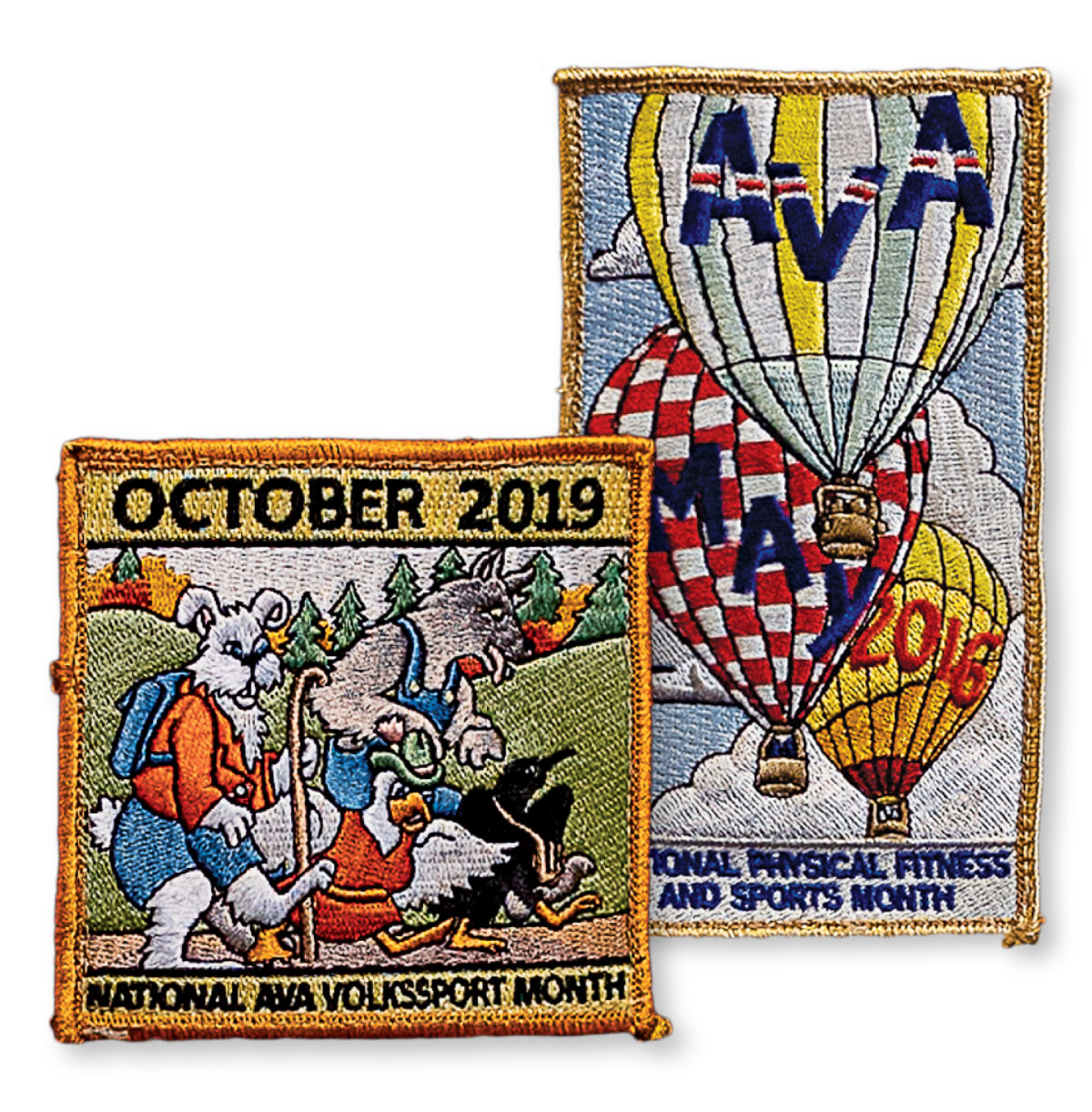

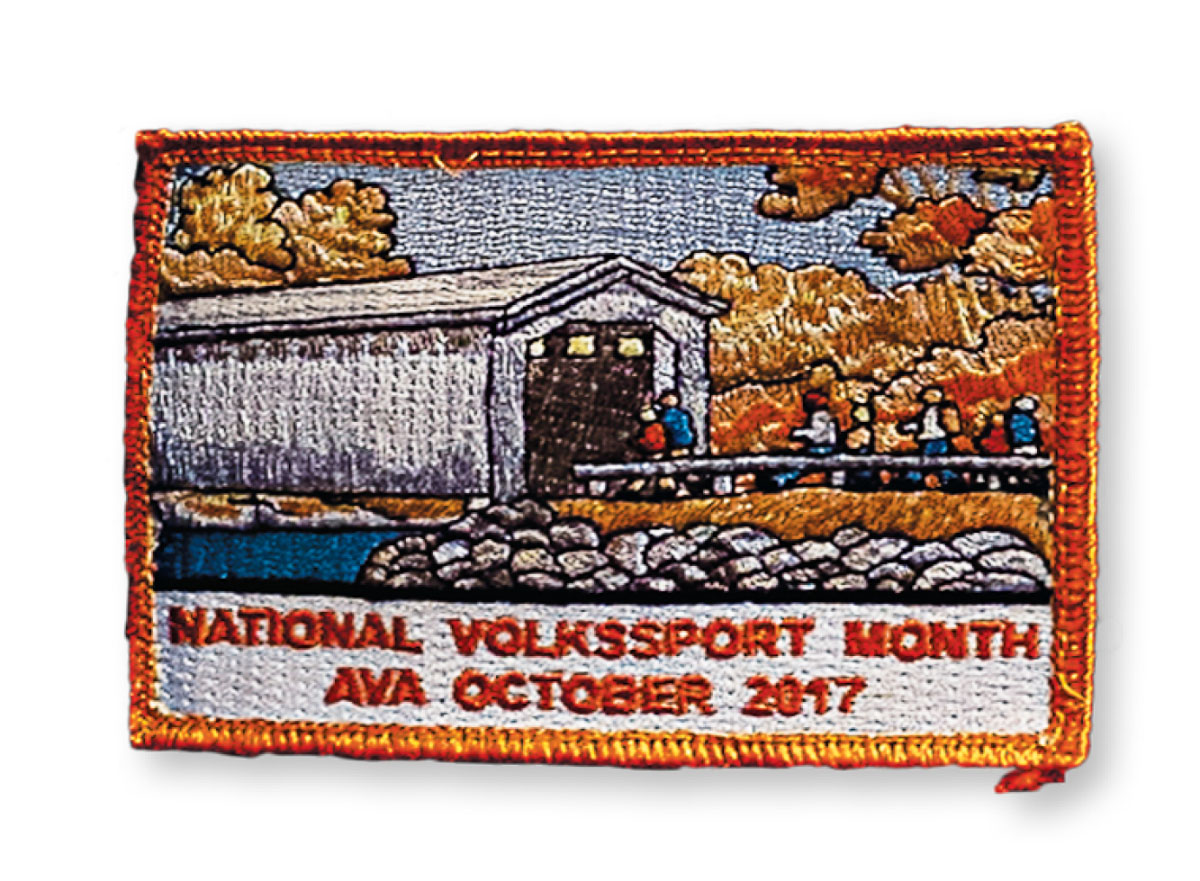

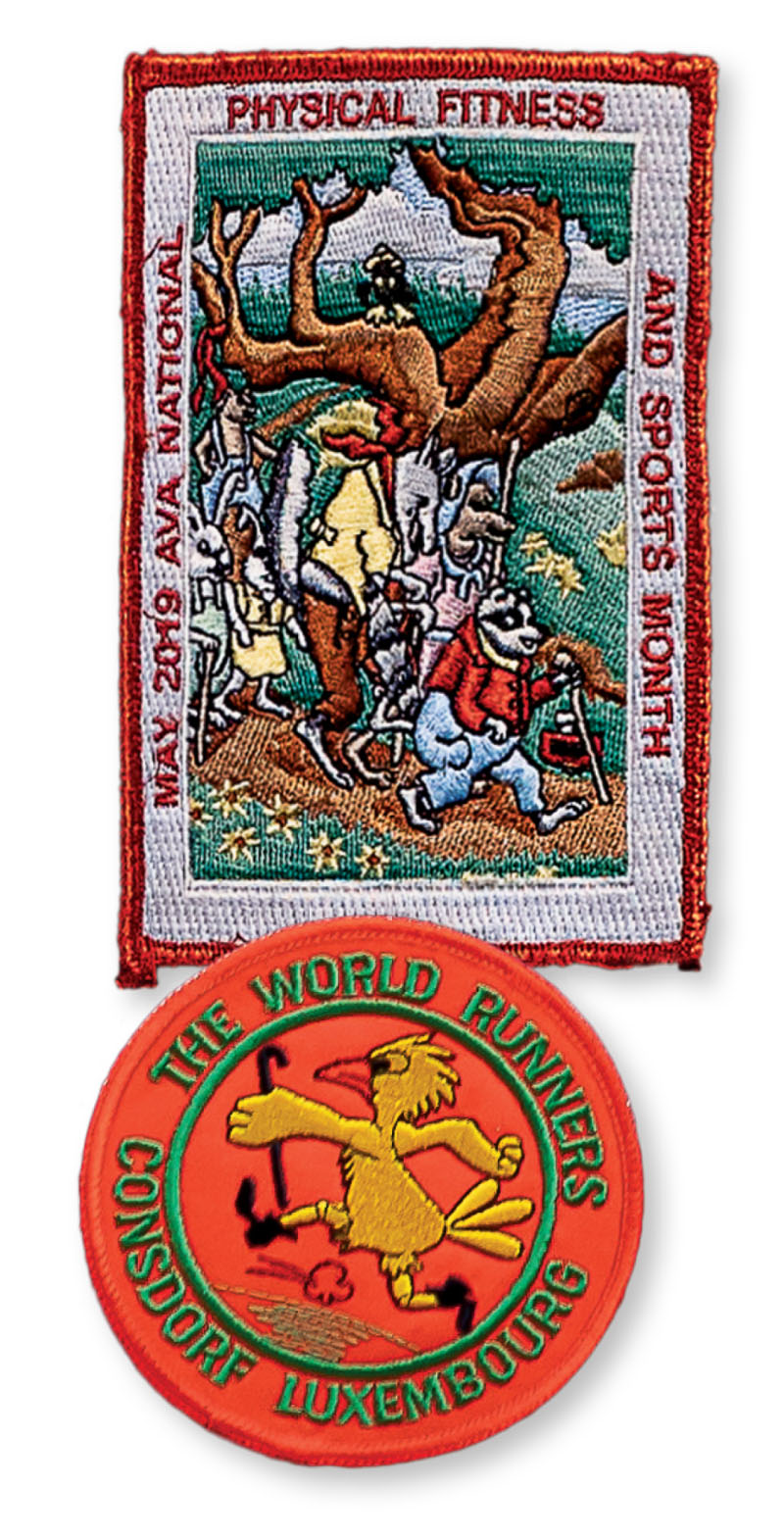

For many like Medlin, volksmarching is more than a hobby; it’s a lifestyle. Veteran volksmarchers plan vacations based on states they haven’t walked in. They’ve filled gold event record books and yellow distance record books, and they’ve covered T-shirts and jackets in achievement patches for events participated in and distance walked. Volksmarchers skew slightly more female than male, most are over 50, and many are still walking well into their 70s and 80s. Even those in their 90s, who can no longer walk long distances, volunteer at checkpoints and finish tables, ready to share a coffee and a chat. For those who have been volksmarching the longest, the sport has cemented decades-long friendships, satisfied a post-retirement call to purpose, and kept them healthy and connected in a time of extreme anxiety and isolation. And it all started stateside in Texas.

“We joke that we’re America’s best kept secret,” says Medlin, now a San Antonio resident and vice-chair of the American Volkssport Association (AVA), a nonprofit headquartered in San Antonio that hosts volksmarching events throughout the country.

Volksmarching falls under the umbrella of volkssports, or “sports of the people.” These evolved from volkslaüfe, public running races sponsored by sports clubs in southern Germany in the early 1960s. Sports are a way of life in Germany, with nearly 90,000 sports clubs and more than 27 million members in the country today. The clubs range from grassroots organizations to professional leagues. Some of these clubs spearheaded the first volkslauf in 1963.

Initially, the races were popular. But then Olympians and other professional athletes began winning all the prizes, with more casual runners sometimes injuring themselves or even dying from heart attacks. By 1965, people were disillusioned with volkslaüfe. Why bother competing if there’s no chance of winning?

In 1968, 10 sports clubs from Germany, Switzerland, Liechtenstein, and Austria joined forces to create a sport that would emphasize camaraderie over rivalry: volksmarching. The inaugural event was a 12K mountain volksmarch departing at 7:30 a.m. from Hotel Altkonig Blich in Hohemark, Germany. According to the event brochure, the goal was to reach the top of Feldberg, the highest peak in the Black Forest. Those who finished in under 2.5 hours would receive a “tastefully designed” medal.

But the charter club members wanted to eliminate the need for finish times altogether, so they founded their own organization, the International Volkssportverband (IVV). Eventually, events expanded to include bicycling, swimming, skiing, and more—though volksmarching would remain the most popular. Today the IVV has 33 member countries, including the United States, representing thousands of clubs and millions of individual members worldwide.

Volksmarching came to the U.S. in 1976 via the Rev. Ken Knopp, a Catholic deacon in Fredericksburg. In 1975, Knopp traveled to Rome for a church meeting, then on to Germany to visit his elderly aunt and uncle, who were avid walkers. Though Knopp was only in his 40s, he struggled to keep up with them. When his aunt and uncle showed him a poster for the IVV, Knopp jotted down the organization’s contact details.

Back in Texas, Knopp wrote to the IVV president, asking him how to host a volksmarch for the following year’s American Bicentennial celebration. As a member of the local bicentennial committee in charge of heritage, Knopp wanted to organize an event that would encourage good health and celebrate U.S. history. He also wanted to pay homage to Fredericksburg’s roots as a hub of German immigration to Texas in the 1840s.

Knopp was of German heritage, and though he’d never participated in a volksmarch, he hosted the first traditional volksmarch event in the U.S. The “Walkfest,” as it was called, featured 6- and 12-mile routes beginning at Vereins Kerche, a historical landmark in Fredericksburg’s Pioneer Plaza, and drew upward of 230 participants.

The event was a success, prompting Knopp to establish the American Volkssport Association, the IVV-sanctioned U.S. governing body of volkssports. Today, the AVA sponsors more than 200 clubs spread across almost every state, which combined host more than 2,500 volkssporting events each year. Texas alone has 29 AVA-sanctioned clubs hosting hundreds of volksmarches each year, along with special walking programs. If you know where to look, volksmarching in Texas is a culture all its own.

One of Medlin’s biggest regrets is the 20-year break she took from volksmarching after she and her husband, an Air Force officer, returned to the U.S. from Germany. In 2010, while stationed in Colorado Springs, Colorado, Medlin saw an advertisement in the paper for an April volksmarch in the Garden of the Gods, a park accented with sandstone formations. “Darren,” she said to her husband, “let’s do this.” They dug out their old distance and event record books and never looked back.

One of Medlin’s biggest regrets is the 20-year break she took from volksmarching after she and her husband, an Air Force officer, returned to the U.S. from Germany. In 2010, while stationed in Colorado Springs, Colorado, Medlin saw an advertisement in the paper for an April volksmarch in the Garden of the Gods, a park accented with sandstone formations. “Darren,” she said to her husband, “let’s do this.” They dug out their old distance and event record books and never looked back.

Several years later, when the Army relocated Medlin and her husband to San Antonio, she joined the Randolph Roadrunners Volkssport Club, one of a half-dozen volkssport groups in the area. Eventually, she volunteered to serve as the club’s vice president. These duties dovetail with her role at the AVA, as well as serving as president of the Texas Trail Roundup. The latter is responsible for a three-day international event that takes place in San Antonio every February.

On a Saturday morning in early December, I meet Medlin in front of St. John Lutheran Church in Boerne for a traditional volksmarching event hosted by the Randolph Roadrunners. Medlin greets me wearing a sequined Santa hat, as promised. A banner strung through a low hedge reads START in bold red letters. At a traditional event, which is staffed by volunteers like Medlin, walkers can start at any time within a wide window—say from 8 a.m. to noon—if they plan to finish no later than three hours after the start window closes. Most routes take two hours to complete at a leisurely pace.

It’s 10 a.m., and despite the generous start window, most of the 80 or so walkers who have signed in so far are either finished or on the trail. Medlin ushers me inside Luther Hall, a community area where a half-dozen volunteers in green Randolph Roadrunners polo shirts make easy, friendly conversation. The air smells like remnants of the free pancake breakfast offered to event participants. Like the first volksmarches Medlin attended in Germany, many traditional events include a social component like breakfast or lunch. Lingering is encouraged, and finishers arrive through the doors flushed and exhilarated.

“Great walk,” one woman tells Ellen Ott, president of the Randolph Roadrunners, before helping herself to coffee. Ott discovered volksmarching in 1984, when she worked as a nurse in the operating room of Walter Reed National Military Medical Center in Virginia. A fellow Army nurse had recently returned from Germany and talked Ott and a third nurse, Linda Goodman, into walking with her.

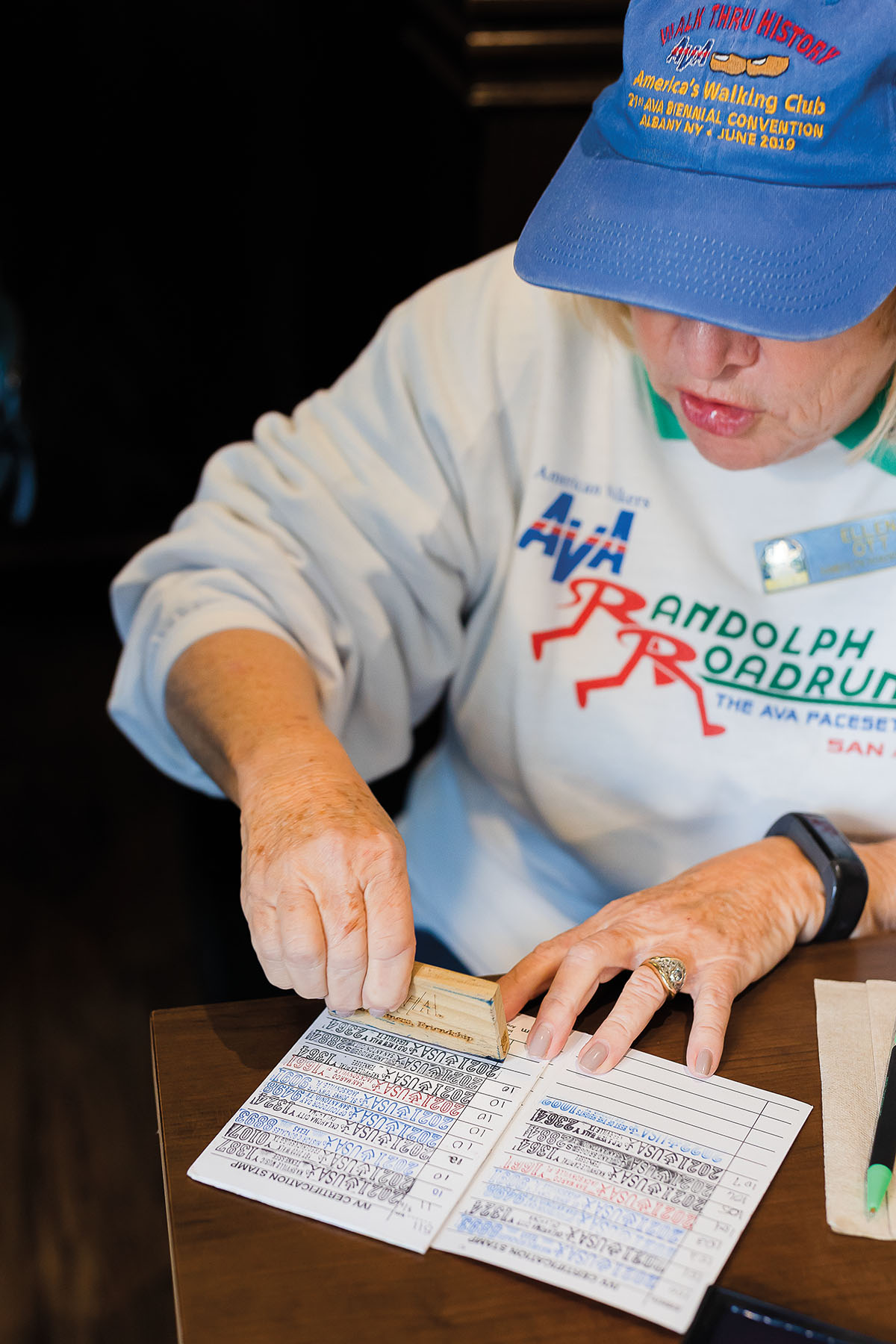

Volksmarching events are classified as either traditional events, such as the Boerne walk, or year-round events (YREs). Both are planned by local volkssport clubs, designed around points of interest, but YREs are not staffed. Instead, from dawn to dusk most days, walkers can find a “walk box”—usually a portable file box—at participating Starbucks, convenience stores, or parks. The box contains a registration log, a printed map, directions for the walk, and an envelope in which to mail $3 to the local volkssport club sponsoring the YRE. Participants don’t need to be members of any volkssport club, but if they are, they can bring their distance and event record books and stamp them with the IVV certification stamp located in the walk box.

“That first walk was in a state park in Virginia,” Goodman says. “It must have been a year-round event because I picture us all together but no other walkers around. It was around the fall, really gorgeous. We relaxed and talked and solved the world’s problems.”

Both Goodman and Ott were hooked. Goodman is now working on 35,000 kilometers and 3,000 events and has walked in every state except Hawaii.

“I have friends all over the United States and really close ones here in San Antonio who I would not have necessarily been introduced to other than meeting on walks,” Goodman says.

Ott became involved with the Randolph Roadrunners in 1990, 10 years after its founding, and finally retired her distance book at 26,000 kilometers. “I was sick of keeping track,” Ott says. But she maintains meticulously organized records of each event she walks. Her numerous patches are sheathed in plastic sleeves she found at Dollar Tree, ideal, she tells me, for how they open at the sides rather than the top. She’s currently working on her second “A to Z Walk”—an AVA special program that includes walking in cities beginning with each letter of the alphabet.

“For Y, we went to Yoakum,” Ott says. “There was only one restaurant that was open, and they ran out of barbecue because we had 100 people there trying to get their Y.”

Near the double doors, Ott shows me an informational table bearing pamphlets and maps of additional AVA special programs—themed events that might include walking by carousels or ice cream parlors, Civil War battlegrounds or Little Free Libraries. Ott is organizing Walk Texas, a year-round event that involves walking in all seven regions of the state: Panhandle Plains, Prairies and Lakes, Piney Woods, Hill Country, Big Bend, South Texas Plains, and Gulf Coast.

In March 2020, the pandemic put a temporary pause on business as usual for volksmarchers.

“There was that initial stunned period where you were afraid to leave your house,” Medlin recalls. So, Medlin built a walk box, got it sanctioned by the AVA, and left it on her front porch for anyone who wanted to walk her neighborhood as a YRE. She walked her own route 100 times that summer, but the day she made it a featured walk for the club, 40 to 50 people arrived on her doorstep.

“We couldn’t stand to not see each other,” Medlin says.

After six weeks of isolation, volksmarchers began cautiously walking together again. Turns out volksmarching might be the ideal pandemic pastime. Walking has profound health benefits, from improving mood and cognition to preventing or managing heart disease, high blood pressure, and diabetes. A study published on nature.com in June 2021 used mobility data from mobile devices as well as area-level data to examine the walking patterns of 1.62 million users across 10 major U.S. cities before and after 2020 lockdowns. The results showed utilitarian walks (to work, for example) decreased, while recreational walks (Sunday afternoon strolls) increased, at least in higher-income areas. One of the study’s conclusions is that equal opportunities to support walking are needed in lower-income areas. Also, a survey from the shoe brand Rockport found 53% of Americans are walking 1 to 5 miles more each day than before the pandemic.

“An active walker is a healthier person,” Medlin says.

Pat Gunter began volksmarching in 1985 as part of her Weight Watchers journey. “They told me I needed to do 300 calories of exercise every day in order to maintain any kind of weight loss,” she says. “Well, I’m 83, and I’m still walking. I have friends who are 85 and 87, and they’re still walking. It’s good for all ages.”

After Ott talks me into becoming a member of the Randolph Roadrunners, I pay $5 for my new walker packet, containing my first record books and coupons for free IVV credit at three events. I fill in my start card and then Gunter hands me written directions for the 5K and 10K routes. I’m on my way.

Once my visit inside Luther Hall ends, I’m leaving at the tail end of the start window and therefore on my own for this walk. Not so a month later when I set out for my second traditional volksmarch event, which starts at Corner Bakery at the Quarry Market in San Antonio.

On a rainy January morning, I join a group of friends who regularly volksmarch together: Sandra Bliss, Thomas

On a rainy January morning, I join a group of friends who regularly volksmarch together: Sandra Bliss, Thomas

Frankhouser, Denise Wanke, Laura Krbec, and Wendy Dylia. Bliss began volksmarching in 2018 with a friend who’d grown up volksmarching in Germany as a little girl. Bliss regularly posts photos of her walks to social media, which intrigued the other women, who knew each other as school parents. Over time, Bliss introduced the sport to Frankhouser and soon they began dating. It poured on the walk, but Frankhouser didn’t complain. “That’s how I knew he could hang with me,” Bliss says with a laugh. Eventually, the group went from friendly acquaintances to real friends who’d one day like to travel together to Germany, where it all began.

Because of the weather, the turnout is small—only 69 walkers. Normally, traditional volksmarches attract 80 to 100 people, though in the 1970s it was common to get as many as 600. The third annual Fredericksburg volksmarch in 1978 drew almost 1,500 participants, including Lady Bird Johnson.

Though I’d only planned to walk a 5K, I’m enjoying the camaraderie too much to turn around at the checkpoint. We push forward toward 10K, passing the mist-shrouded St. Anthony de Padua Catholic Church and winding through the architecturally diverse neighborhoods. We talk about everything from the impact of the pandemic on schools to the impact of pregnancy on our bodies.

We arrive back at Corner Bakery grinning and slightly breathless. Bliss smiles contentedly and says, “It’s walking therapy.”

One Step at a Time

Volksmarching consists of informal year-round events and regulated traditional events. There are too many YREs to list, but a selection of upcoming traditional events are listed below. For more information, contact the American Volkssport Association, 1008 S. Alamo St., San Antonio. 210-659-2112; ava.org

April 2 – Castroville

San Antonio Pathfinders

Castroville Regional Park,

816 Alsace Ave.

Contact: Mike Schwencke

April 9 – Richardson

Dallas Trekkers

Point North Park,

725 Synergy Park Blvd.

Contact: Deborah Carter

April 16 – Comfort

Hill Country Volkssportverein

Comfort Park, 630 SH 27.

Contact: John Bohnert

April 23 – New Braunfels

NB-Marsch-und Wandergruppe

Casa Garcia’s Restaurant,

1691 SH 46.

Contact: Jan Engel

April 30 – Bastrop

Colorado River Walkers

Fisherman’s Park, 1200 Willow St.

Contact: Carol Obianwu

May 14 – Hurst

Tarrant County Walkers

Chisholm Park, 2200 Norwood Drive

Contact: Brooke Hudson