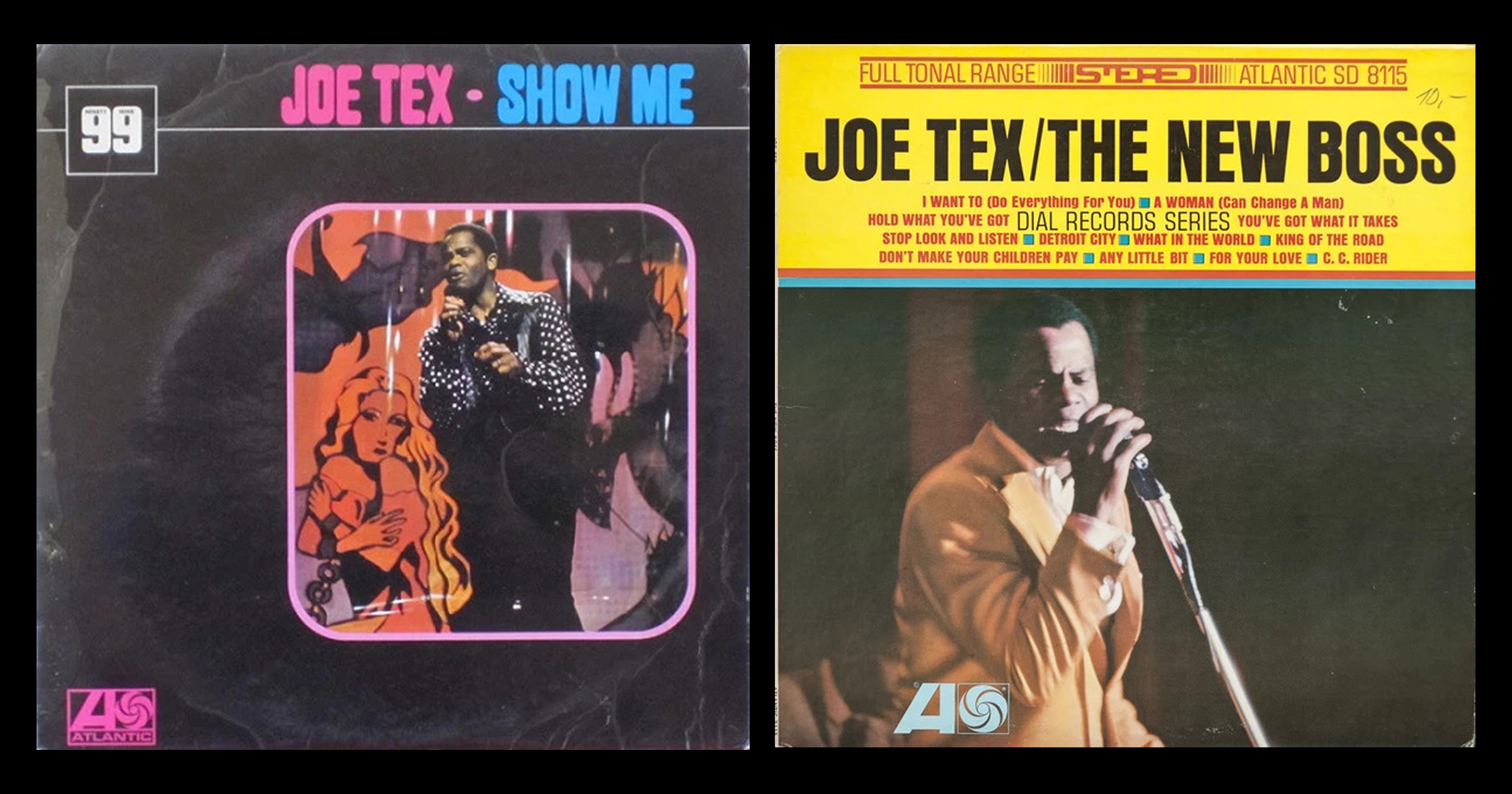

Joe Tex albums Show Me and The New Boss

In Navasota, there’s a bronze statue of a guitar-strumming Mance Lipscomb in a park named after the famous bluesman. In 2005, the town was designated the Blues Capital of Texas because of its native son. But if you venture about 5 miles away to Dennis Bryant Cemetery, you’ll find a memorial of sorts to another music legend who lived out his final years in this Brazos Valley town. On the left side of the cemetery in row 20 is the grave of Joseph Arrington Hazziez, aka Joe Tex.

Born 86 years ago on Aug. 8, the Lone Star State soul music legend might not have been blessed with the golden tenor of a Johnny Nash or Sam Cooke, nor the raspy raw power of a Wilson Pickett or Otis Redding. And yet with his impeccable phrasing and ability to shift in and out of spoken word to soaring vocals, Tex was every bit the all-around singer of many a man blessed with better tools.

What’s more, Joe Tex brought to his music a level of complexity many purer singers did not. In mixing his sermonettes—mostly exploring the ins and outs of the battle of the sexes—with a wry sense of humor that masked great profundity, many of his records came across more as productions than mere songs.

“Few pop singers articulated more fearlessly, or more accurately, the mutual vulnerabilities between men and women,” wrote the late Texan pop critic John Morthland, adding that Tex had a “Black preacher’s ability to bring a laugh with his moralism, but plain old country horse sense was his truest guide.”

Jason Martinko, author of the 2018 Joe Tex biography, Hold What You’ve Got, said via email that a full-length treatment of Tex’s life was “long overdue,” pointing out Tex’s range went from rhythm and blues to rock ‘n’ roll to country, gospel, and funk. Racking up 4 million-selling hit singles along the way, he also inspired James Brown, Johnny Cash, Liza Minelli, and Etta James to cover his songs.

“Joe Tex is perhaps the most overlooked singer and songwriter in the history of American soul music of the 1960s and ’70s,” Martinko states flatly.

Joseph Arrington Jr. was born in the tiny Temple/Killeen-area town of Rogers (also the hometown of dance legend Alvin Ailey) and raised in the all-Black town of McNair, 4 miles north of Baytown. There he attended the community’s segregated George Washington Carver High School, where he was Mister Everything: a football player and hurdler on a state championship track team; a trombone player in the band; and student body president, all in addition to commanding stages with his words, both spoken and sung, and his athletic dance moves.

Arrington was a natural-born, all-around performer.

While the hit records would be slow in coming, Arrington vaulted straight into the upper echelons of the recording industry even before he got out of high school. During his junior year, he entered a talent show in Houston and defeated eventual “I Can See Clearly Now” singer Johnny Nash and Hubert Laws, a jazz and classical flautist who would become a National Endowment for the Arts-designated Jazz Master.

Arrington’s winning performance was telling—it was his rendition of a part-sung, part-orated comedy routine called “It’s in the Book.” The 17-year-old boy would become the man: After years of trying and failing to make a hit single singing more traditionally, he would fall back on this formula and make it his own.

First prize in that contest was $300 and a week’s stay in Harlem, where Arrington entered the weekly Amateur Night talent show at the Apollo Theater. He won it four weeks in a row. Break followed break and by the time he was 19 years old, he’d adopted his “Joe Tex” stage name and signed with King Records, where he was labelmates with the man who would become his rival: James Brown.

While his amazing performances made him a popular live attraction, it took a decade for him to score a hit: 1964’s “Hold What You’ve Got,” a deeply soulful meditation on romantic gratitude and basic decency. From then until the late ’60s, Tex was ever-present on the charts, highlighted by soul jams like “Show Me” and the good-time jam “Skinny Legs and All.”

In “Men Are Gettin’ Scarce,” Tex humorously evokes Juneteenth in a spoken-word section: “She reminds me of them folks up in Navasota, Texas, eatin’ barbecue and drinkin’ red soda water on the 19th of June. Look here, give me a piece of that barbecue, and kiss me with your greasy mouth.”

According to pop critic and soul music scholar Peter Guralnick, soul music died upon the assassination of Martin Luther King. “Soul was the music of hope and the product of a hopeful era, and I think the worst aspect of its decline was the climate of distrust that arose after the death of Dr. King,” he once said.

It appeared to affect Tex’s career. The hits slowed to a trickle in 1969 and 1970, and “I Gotcha,” Tex’s comeback hit of 1971, was a chunky pounder of a funk song. (Later deployed to memorable effect in Quentin Tarantino’s Reservoir Dogs.)

By this time Tex had settled on a ranch outside of Navasota and had become a disciple of the Nation of Islam. He took the name Yusuff Hazziez and stopped performing, instead preaching the word of his new faith. After requesting permission from the Nation of Islam to resume performing, the singer had one more comeback in him with a novelty song mocking a disco dance trend, “Ain’t Gonna Bump No More (With No Big Fat Woman)” in 1977.

Sadly, after decades of temperance, Tex succumbed to drugs and alcohol in his final years. As smart as he was, he was no businessman, and he was drowning in debt, fueling his addictive shame spiral. Aside from his family, the abiding joy in his life was his love of the Houston Oilers, one of whom was praised in Tex’s final recording: “Here Come Number 34 (Do the Earl Campbell).”

Days after nearly drowning in his swimming pool, Tex died of a heart attack on Aug. 13, 1982. He was 47.

“It’s been nice here, man, a lot of ups and downs, the way life is, but I’ve enjoyed this life,” Tex told Guralnick in his final years. “I was glad that I was able to come up out of creation and look all around and see a little bit, grass and trees and cars, fish and steaks, potatoes. … And I thank God for that. I’m thankful that he let me get up and walk around and take a look around here, ’cause this is nice.”