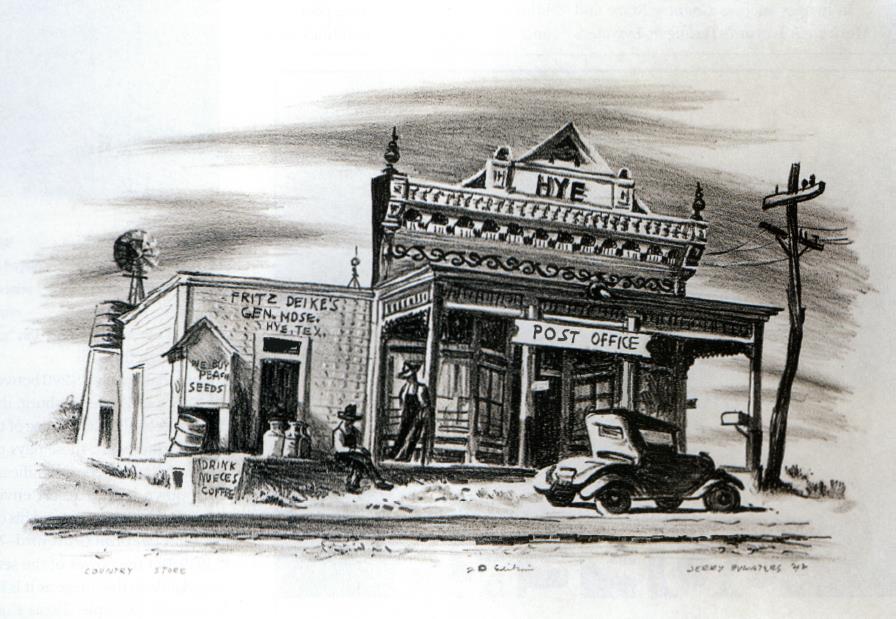

The 1942 lithograph Country Store documents typical Hill Country architecture. The building. located on US 290, is still in use. Photo courtesy of the Jerry Bywaters Collection on Art of the Southwest, Hamon Arts Library, SMU

It’s rare for an artist to establish a genuine, specific, and objectively acknowledged sense of place in his or her work, but Jerry Bywaters beat those odds by capturing a palpable sense of Texas and the Southwest through his paintings and prints. Now, 20 years after his death, Bywaters’ work seems to be even more widely appreciated than it was during his career.

Bywaters began documenting details concerning his prints in 1935, so there is a personally inscribed record of his 13-year printmaking career. This meticulous history is just one piece of background that makes a current museum exhibit, and a related book, all the more engaging. Jerry Bywaters’ regionalist prints transport you back to the land, even as they instill an appreciation for a number of memorable landmarks.

The exhibit, titled Jerry Bywaters: Lone Star Printmaker, is on view at the University of Texas at Austin’s Blanton Museum of Art through November 8. I

was glad I got the chance to see the work in person, but I’m also enjoying the book with the same title, published by Southern Methodist University Press.

Even though the exhibit’s run is limited (I’m hoping it is picked up by another museum in the state), the book contains most of what makes the exhibit special, albeit in a smaller format. Both book and exhibit explain Bywaters’ importance as a printmaker, and his mission to make the prints themselves available for public view by a broader audience.

In images such as Country Store and Mexican Graveyard-Terlingua, Bywaters conjures a vivid spirit of places in the Lone Star State that travelers can recognize—and visit—today. Even though his work ranges from the most direct “documentary” approach to more highly stylized images, the powerful, humanitarian ties to geography are vibrantly alive.

In the example of Country Store, a lithograph depicting the Hye post office and adjacent store, the buildings today appear surprisingly similar to the way

they do in the image drawn by Bywaters in 1942. Even whizzing through this Hill Country hamlet on US 290 between Johnson City and Fredericksburg, it’s easy to catch a recognizable glimpse of the scene. Much farther west, these days the cemetery in Terlingua seems significantly more worn down by the desert environment than when Bywaters created his original lithograph, Mexican Graveyard-Terlingua, in 1939. But the power of the setting is as remarkable in the image as it is in person. In another example, Texas Courthouse, Bywaters employs a hint of the surrealist style, and in yet another, Big Bend Country, he creates a cubist attitude with a cluster of adobe houses. But the essential sense of place is still vivid.

Once in the Blanton’s contemporary galleries, but before you enter the Lone Star Printmaker exhibit, make a short pilgrimage to view Bywaters’ iconic

painting Oilfield Girls (in the Blanton’s permanent collection). The popular painting is often on loan to other museums, but when it is in residence, it hangs in the same space as Thomas Hart Benton’s painting Romance. It is appropriate to view these two paintings together before visiting the Lone Star Printmaker exhibit in the adjacent two rooms of the Blanton’s contemporary galleries, because, in the artistic sense, Bywaters and Benton are stylistically and conceptually cut from the same cloth.

Humanism adds a visceral note of social commentary to Bywaters’ regionalist sensibility. The oilfield girls transmit the only hopeful color in a bleak West Texas landscape, and they’re ready to hitchhike out of the forsaken setting. Whether or not the two women are prostitutes, as is often postulated, doesn’t change their inferred need or intention to be well rid of the oil field squalor. Benton’s painting features an African-American couple in hardscrabble circumstances that seem somewhat more poetic in that the scenario is rustically rural, but there is, nonetheless, an ominous vibe that drives the couple. Both images offer a glimpse of a tough socioeconomic reality, but the media mastery that empowers the telling of the story elevates each image to its artistic height.

Early in his career, Bywaters revered Thomas Hart Benton as an inspirational figure, and the influence is clear in his work. Benton, who acknowledged Bywaters as an accomplished artist, set the 20th-Century standard for the school of artistic thought, belief, and practice called regionalism, and Bywaters closely followed Benton’s lead. The tenets of regionalism suggest that artists should study their environment to find appropriate subjects for their work. It’s important to point out that regional does not translate to mean “unsophisticated.”

Bywaters became identified with a group of local artists, active in the 1930s and 1940s, known as “The Dallas Nine;’ who all developed the sense of regionalism. As author Ellen Niewyk explains in the book, “as they developed the concept of Texas Regionalism-it occurred to them to say ‘let’s study what’s in our environment.'”

Bywaters seems to breathe the sensibility of land and people, and then employs his artistic voice to relay regionalism’s values to viewers. The easily

accessible, down-to-earth scenes made his work popular, and he attained a level of success during his lifetime. The Lone Star Printmaker exhibit at the Blanton, organized thematically rather than chronologically, relates an overview of Bywaters’ evolution as artist and his mastery of the printmaking techniques.

As Risa Puleo, the Blanton’s Assistant Curator of American and Contemporary Art, explains, “The show demonstrates that Bywaters was as important a person as he was an artist.” It was Bywaters’ personal energy and passion that propelled him into long-running positions as Director of the Dallas Museum of Fine Arts, as art reviewer for The Dallas Morning News, and as mentor to and collaborator with many artists of his time.

Indeed, it was a personal relationship that brought author Ellen Niewyk into the realm of curating his collection. “I knew Mr. Bywaters since I was in graduate school in 1976 through 1978, and he hired me in 1987 to work with his collection. The collection was in a rather small room. He had donated

the work to Southern Methodist University in the 1970s.”

In addition to Bywaters’ art prints, the exhibit includes a sampling of the artist’s designs and illustrations, some for art projects he promoted, such as a program suggesting that students “Study Art in Mexico.” In Mexico, Bywaters furthered his philosophical understanding of regionalism by studying the work of that country’s artists, including muralist Diego Rivera. The print Lily Vendor is strongly reminiscent of Rivera’s work. And the social commentary

that runs so strongly through Rivera’s work is an important component of the regionalists, including Bywaters.

If you really get the Bywaters craze, check out Jerry Bywaters: A Life in Art, written by Francine Carraro, now the executive director of Abilene’s Grace

Museum. The Carraro book is out of print from its original publisher, The University of Texas Press, but is available online.

Whether you visit the Blanton or peruse the books mentioned, you’ll find that Bywaters’ art is work with a mission, and you’ll be able to share the artist’s

views of the state, in terms of geography, sociology, and architecture.