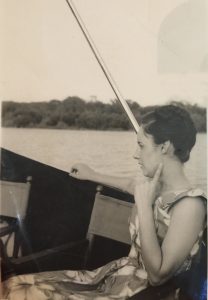

Beverly Sheffield (left), former Director of the Austin Parks and Recreation Department, teaches swimming in 1931. Courtesy Lois Sheffield.

In 2017, a developer wanted to turn an office complex into a mixed-use development, but to do so he needed to cut down several mighty oak trees protected by a city ordinance. In the hope of stopping the deal, environmental activists named the beloved trees after musical icons such as Patsy Cline, Waylon Jennings, and Willie Nelson. Ask yourself, could this have happened in any city but Austin?

For many of its residents, Austin has always been green, in its parks and public spaces, as well as its politics. The only major development to the city’s popular hike-and-bike trail downtown is the name of the lake it encircled. (Boring Town Lake fittingly became Lady Bird Lake.) And it’s almost impossible to imagine Austin without Barton Springs, its famed spring-fed community pool, and the surrounding Barton Creek Greenbelt.

What’s surprising is “how easily it could all not have happened,” said Karen Kocher, the co-writer and co-director with Monica Flores of Origins of a Green Identity, a documentary about Austin’s conservation pioneers. The hour-long movie, narrated by Texas author and Barton Springs junkie Sarah Bird, premieres Dec. 29 on Austin PBS. “The people who enjoy the hike-and-bike trail, they don’t really have much of an idea of how it came to be and how it was driven by people in the community.”

The heroes of Origins’ story are Roberta Crenshaw, a wealthy activist who became Chairman of the Austin Parks Foundation, and Beverly Sheffield, the longtime Director of the Austin Parks and Recreation Department. From the 1950s to the ’70s, development and real estate forces drove the votes on the all-male Austin City Council, but Crenshaw’s pugnacious activism and Sheffield’s moral determination moved the needle on green-space conservation in Austin from a good-to-have to a must-have.

Roberta Crenshaw, former Chairman of the Austin Parks Foundation, saved Town Lake. Courtesy Noelle Paulette.

In one particularly vivid sequence in the documentary, Crenshaw lobbied to stop an effort to privatize Town Lake and build an amusement park called Little Texas. She convinced the bankers behind the deal to get councilman Ben White to switch his vote and kill the deal. Mayor Lester Palmer’s comment opened a window on the sexism Crenshaw faced at the time.

“History records it only took one snake and one little woman to ruin the most beautiful garden on earth,” said Palmer, whose name adorns the event center on the shores of the lake that “little woman” successfully protected from private development.

“They didn’t tolerate me too well,” Crenshaw said then.

Crenshaw’s victory led to efforts to preserve the Greenbelt, then undeveloped and privately owned, with Crenshaw fighting from the outside and Sheffield from the inside. But the great insight of Origins of a Green Identity isn’t that the preservation of Austin’s green space was in doubt for most of the 20th century. What Origins dramatizes is how Crenshaw’s creation of the Austin Environmental Council, an activist group, began the environmental movement in Austin. This fundamentally and enduringly changed the capital city’s politics. Soon thereafter, the Office of Environmental Resource Management was established and along with it a citizens’ board, where developers and preservationists jointly hashed out recommendations.

Crenshaw’s and Sheffield’s “successes weren’t in getting a lot of the Greenbelt preserved,” Kocher said. “Their successes were the beginning of the institutionalization of environmental values within the city.”