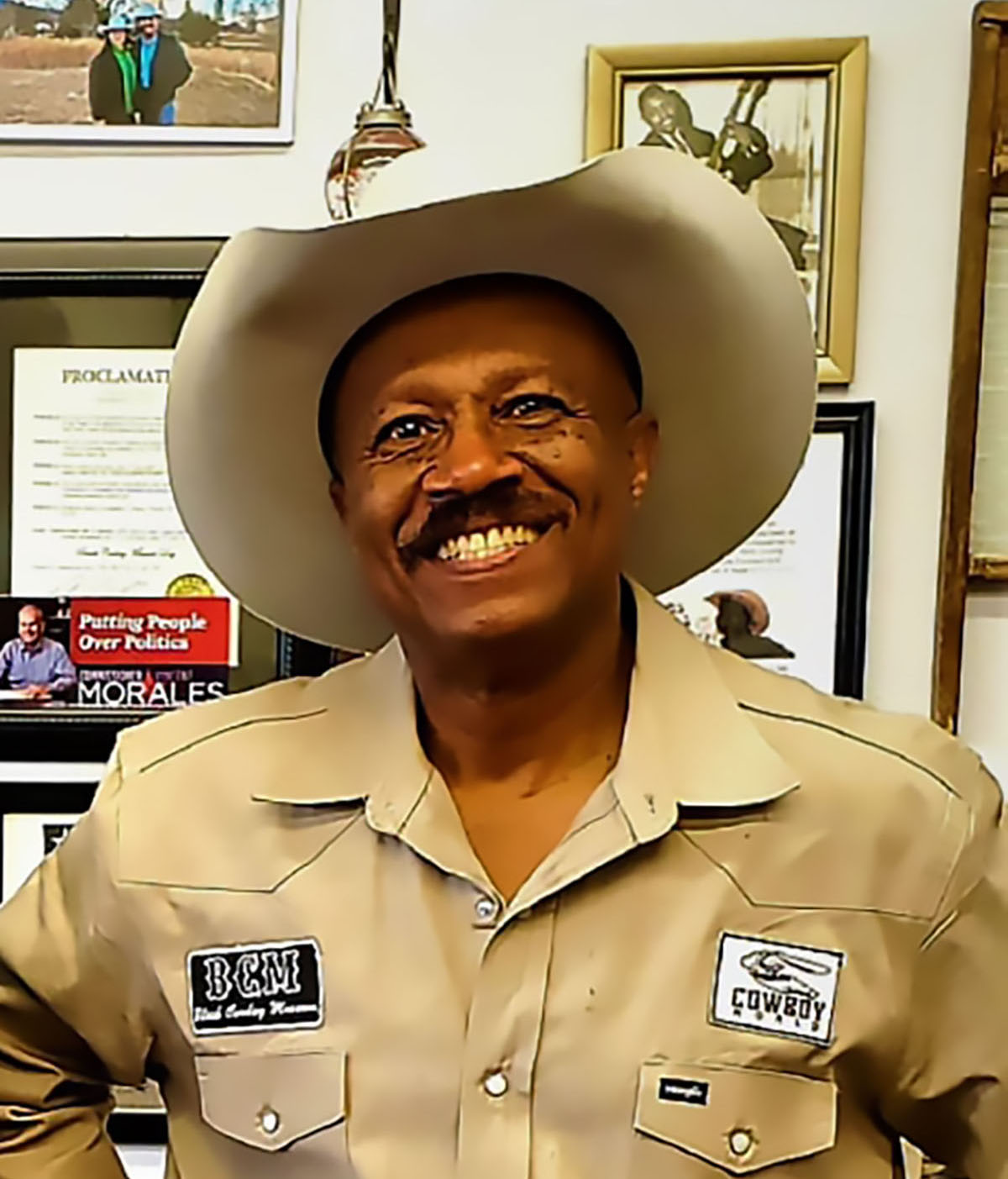

Larry Callies, the founder and operator of the Black Cowboy Museum. Photo by W.K. Stratton.

It may seem strange to start a tour of the Black Cowboy Museum in Rosenberg with a discussion of who invented the telephone and the incandescent lightbulb. But Larry Callies, the museum’s founder and operator, has a point to make: Lewis Howard Latimer, a Black man with a profound grasp of the technology of his day, made essential contributions to the creations credited to Alexander Graham Bell and Thomas Edison, though history books ignored him.

The same holds true for Black cowboys, Callies explains. Their heritage has largely been unknown outside of Black oral tradition. “White people wanted to keep it all hid,” he says.

Callies, who opened his museum in 2017 to both unhide the legacy of Black cowboys in America and to set the record straight, began collecting material for it 25 years ago. The small storefront space that used to be a barbershop in a strip center north of downtown is crammed with books, magazines, clipped articles, photographs, and artifacts like chaps, boots, and saddles. It is all laid out over two rooms: the first focused on early day Black cowboys, the second on Black rodeo.

The exhibits have a homegrown feel to them and change only as more material shows up. There is plenty to see. A print of a 1908 painting, “The Stampede,” by Frederic Remington catches my eye. It features a Black cowboy galloping on a horse in an attempt to contain cattle spooked by a thunderstorm. I’ve seen dozens of Remington paintings and sculptures in my time, but I never realized he included Black cowboys in his work until today as I make my tour of the museum.

Callies, as storyteller and self-taught curator, is the museum’s main attraction. The 69-year-old’s family roots in the coastal plains west of Houston—long a rich cattle-producing area—extend back to the time of slavery. He’s been mentally recording cowboy history going back to his childhood, when he’d listen to stories told by his uncle Willie, who was born in 1919. It was from Uncle Willie that Callies first learned how the term cowboy itself came into use in Texas.

“There was a time when you didn’t call a white man a cowboy,” Callies says. “White men were called cow hands or cow men or cow punchers or cow drivers. But you better not call him a cowboy. Black people were the cowboys. Among slaves on plantations, you had the ‘house boy.’ A ‘yard boy.’ Somebody who worked the cows, he was called the ‘cow boy.’ That’s how it was here in Fort Bend County. And the counties all around Houston. That’s how the word cowboy came about. In Texas, among white people, cowboy was a nasty name.”

It remained a derogatory term until the early 20th century, Callies says, when its use in popular Wild West entertainment such as movies changed the connotation.

Beef production is an often-overlooked part of antebellum Texas. Slaves learned how to herd dangerous, feral Longhorns that grazed in abundance on the coastal plains. Forget about John Wayne and Montgomery Clift in Red River. After emancipation, it was those ex-slaves who became the cowboys on the first cattle drives, which traversed Texas then moved along trails through Indian Territory to markets and railheads in Missouri and Kansas.

“In the last few years,” Callies says, “people have wanted to know the history, the true history, not the lies that they’ve read in books. If you saw 10 cowboys, one or two were white, the rest were Black. At least down here.”

Callies also wants to make sure museum visitors learn about Black contributions to contemporary cowboy culture, especially rodeo. His father was hired on with Sloan Williams Cattle Company in Hungerford at a time when it was one of the largest rodeo stock contractors. Callies himself worked for Williams for 20 years. In 1971, he became just the second Black cowboy to make the state finals in high school rodeo. His cousin, Tex Williams, was the first three years earlier. “Before that, they wouldn’t let Blacks come around high school rodeo in Texas,” he says.

Legends like Crockett’s Myrtis Dightman, the bull-riding “Jackie Robinson of rodeo,” are honored in the museum’s hall of fame. (Inductions into the hall of fame are one of the special events held here; others are keyed to holidays like Christmas.) Dightman was the first Black cowboy to compete in the Professional Rodeo Association National Finals Rodeo. Another honoree is the late Calvin (Pop) Greeley Jr., of Wharton, who helped break the Professional Rodeo Cowboys Association color barrier and who was, in Callies’ estimation, the best tie-down roper of all time, though for many years he could only compete at all-Black rodeos.

As a young man, Callies focused on a career as a country music singer, hoping to follow the footsteps of his idol, Charley Pride. But two weeks before he was to get a shot in the recording studio, he lost his voice. It never returned in full because of a congenital nerve issue with his vocal cords. Nowadays Callies views it as a step along the way toward his true calling. “It was a blessing,” he says. “I wouldn’t have this museum if it didn’t happen. God didn’t want me out there with them singers.”