The cemetery where Buddy Holly is buried is located on 31st Street in Lubbock.

Two winters ago, my friend Cameron Knowler and I were touring across Texas, playing concerts of instrumental music referencing jazz, country, and avant-garde guitarists to anyone who’d listen. We were traveling from Houston to the Trans-Pecos—Dallas, Lubbock, Big Bend, Austin, and back home—in an oblong loop around the state. One morning toward the end of December, as we listened to Buddy Holly sing on the car stereo, “You are my one desire/ You set my heart on fire,” we remembered that he had died in a plane crash in 1959, and decided to visit his burial site on the way out of Lubbock, where we had played the night before.

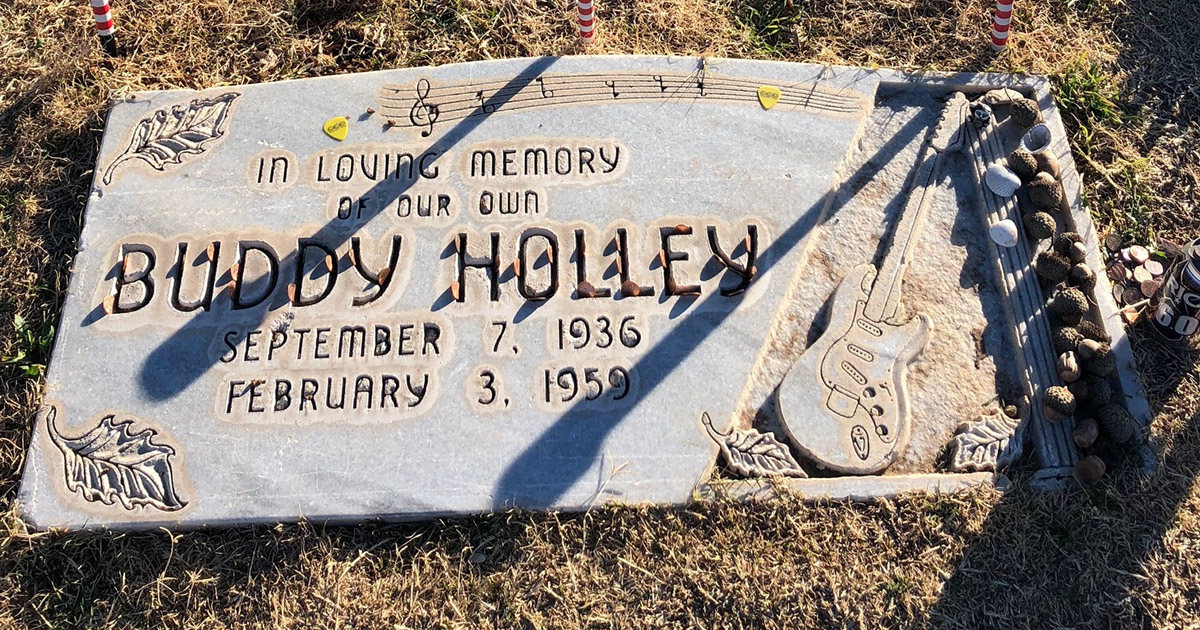

In many ways Lubbock is typical of cities scattered across West Texas. Squat, vintage buildings line its arterial roads. Bars bear signs reading, “NO BANDANAS NO DO RAGS,” “PROPER DRESS REQUIRED,” and “SMOKING ALLOWED INSIDE.” And its sky spreads vast and rich over ranch houses, university buildings, and oil derricks. The cemetery where Holly is buried, located off 31st Street, sits near an eerie industrial area nestled between abandoned railroad lines, two highways, and a lake. We pulled up to its gravel entrance and hopped out of the car, stumbling around the grass as we looked for Holly’s clearly marked headstone, which reads BUDDY HOLLEY, after his birth name.

Memories of last night’s concert lingered in our minds: the smoke and crowd noise overpowering our guitars, the luck of a generous guarantee. As we stood over his grave, we noticed that he was about our age, 21, when he died. Later, stopping for gas or photos or a meal in small, bare towns like Grandfalls and Marathon and Alpine, I wondered when our luck might run out.

We had gone to Far West Texas in the dead of winter, when temperatures hovered around 30 degrees and plucked cotton fields lined the roads. Cameron was familiar with the terrain, having spent the first half of his life in Yuma, Arizona, largely homeschooled and amused by the snowbirds who packed their trailers near his house when it warmed. After a few tense moves between Houston and Austin, he settled in Houston to be near his grandparents. But the desert exerts a strong pull.

Meanwhile, the Trans-Pecos holds my fascination like a cactus does water, and has ever since my family road tripped there. But I spent much of my childhood within a small radius around my family’s home in Houston, and envied my friends who could head to Fort Davis or Big Bend by themselves for a long weekend. Ever since moving to Chicago for school and music, I come home each winter and leave less sure that I’ll be back.

One man’s trash is another’s treasure.

We had played countless concerts despite our ages, starting, independently of each other, in our teens. Cameron, a self-taught bluegrass guitarist with a jazz degree, had accompanied a series of songwriters on tours of Texas and the South, playing lead guitar at honky-tonks, house shows, and cafés. Following in the footsteps of mentors and friends, I had played dozens of gigs in basements, galleries, and art bars to hone my instrumental guitar music, often to crowds of 10 or fewer. To my mind, the mild humiliation of playing background music in coffee shops, with such trepidation that people dropped dollar bills in my guitar case out of pity, would mark a small step toward scaling up my concerts to a respectable size. Someday, I thought, I’d play real music venues and go on real tours. Thus far, Cameron and I had toured twice together with others. These were hardscrabble tours, usually playing to no one or an uninterested handful. Sometimes we were paid in free coffee. This time, we said, would be different.

But tours take months to book, and paying gigs are hard to come by if you book your own, as we do. In Austin you might lose money just trying to get a room. Far West Texas presents its own challenges. Dallas to Lubbock, five hours. Marfa to Austin, six—if you speed. If you play with more than two people, if your music doesn’t make oldsters at the bed-and-breakfast slack their jaws or swing their hips, you might be better off hedging your bets and blazing down Interstate 10 to the next gig. We leaned into the challenges of Far West Texas, savoring the landscape, spare and rugged, as we drove through.

We had agreed early on to stop at anything that seemed serendipitous or strange, to avoid the tensions of traveling in close quarters. In the old Terlingua ghost town, there’s a vibrant community of folk musicians who organize the Voices From Both Sides music festival at the Lajitas border crossing, and who also play fiddle tunes on the porch of the Starlight Theatre after dark. We played with them. Two-and-a-half hours south of Lubbock, on the way to Alpine, we stopped on a whim at the Odessa Meteor Crater, a giant depression sunken into the sparse landscape. I walked in without thinking, against the rules, and nearly caught myself in its bramble. Another night, brittle and crisp, Cameron and I drove to see the Marfa Lights. Residents first noticed them in the late 1800s. If you look off to the far-right corner of the horizon, down past the Chinati Mountains, you can see small dots—white, red, green, and off-gold—change colors, converge and disappear. No one knows why this happens. Cynics suggest they’re headlights driving down the far highway. I prefer the serendipitous view.

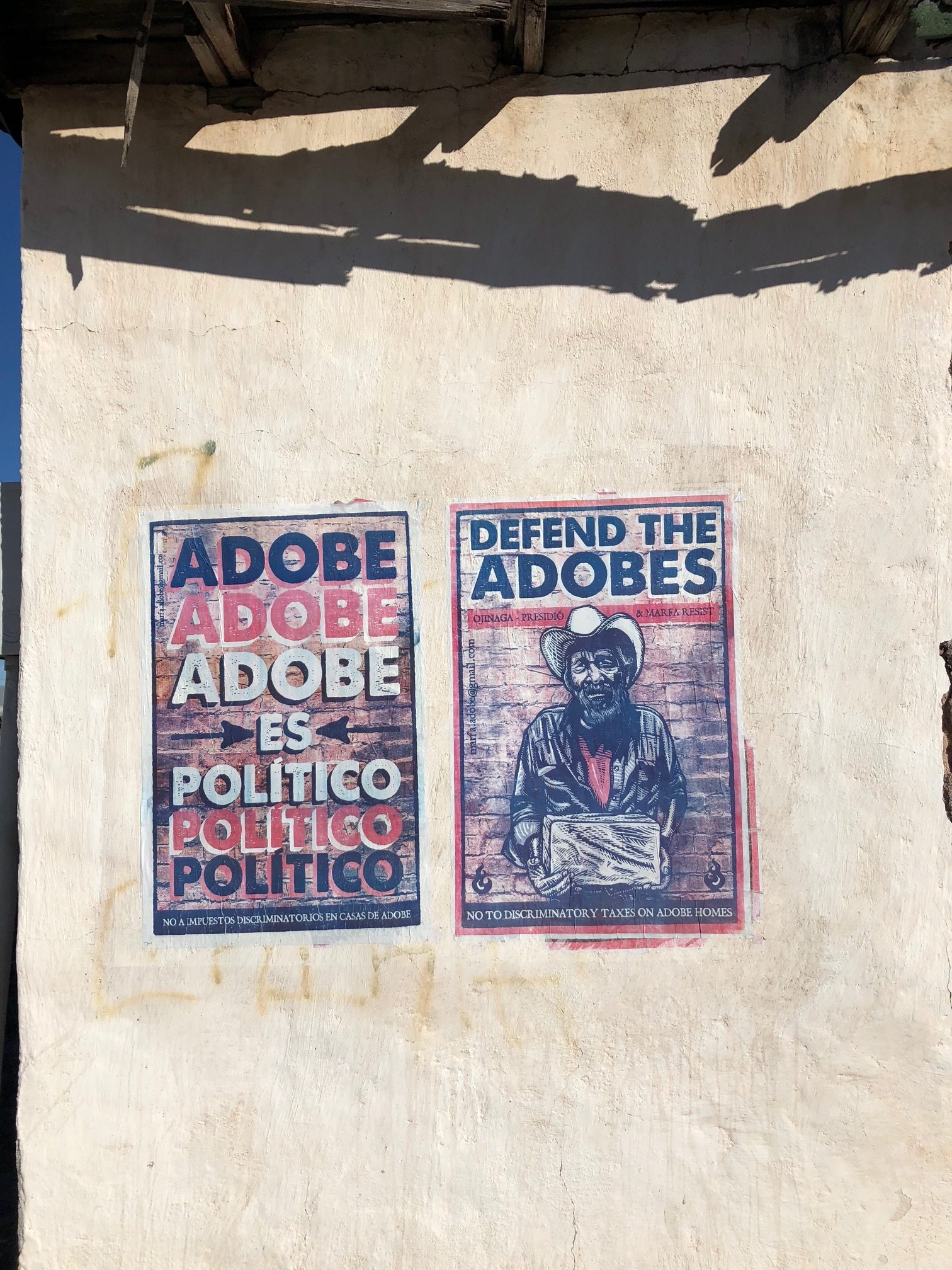

Politics in Far West Texas.

Touring threads the needle between strenuous effort and serendipitous discovery. Each night presents a seemingly infinite set of variables, several of which threaten to undermine the whole endeavor. Some nights you get a guarantee; others, you make Whataburger money. You can sleep comfortably on bedrolls in a trailer or crash at a house with so much cigarette smoke that you sneeze through the night.

Surely Buddy Holly, who gave a concert almost every night for nine months in 1957 and ’58, knew the difficulty of asserting oneself as a musician in the face of incredulous listeners. For Holly’s second appearance on The Ed Sullivan Show, Sullivan muted the volume of Holly’s guitar while introducing him as “Buddy Hollet,” though Holly twisted the volume knob on his guitar as he played. Before Sullivan, before theaters and arenas, Holly played local elementary schools, American Legion Centers, music stores—not unlike the first concerts Cameron and I gave, and will probably continue to give.

Such shows mark the province of most working musicians. Most won’t ever play arenas or theaters; fewer still will be famous. Organizing a life around working as a musician full- or even part-time is intense. A promoter tries to stiff you, or takes tips instead of the door. An audience member tries to haggle with you for merch. Rosanne Cash upstages your gig with a free show across town. Who wants to play background music at wine bars for rent money? Who cancels a gig to have heart surgery after decades of playing every tiny restaurant back room they book? People like me, who live by the words on Holly’s grave: TO LIVE IN HEARTS LEFT BEHIND IS NOT TO DIE.

Tell us about your favorite Texas trip

Share your story with us! Select responses may be published on texashighways.com.

“My Favorite Texas Trip” is a series highlighting memorable travel experiences from Texas Highways’ writers and readers.

Read the rest of the series here.