Annette Bernhard Nevins photographs her three children at the mission’s Rose Window in 1999. Photo courtesy Annette Bernhard Nevins

The bells of Mission San José set the pace for everything I did growing up in 1950s-’60s South Side San Antonio—just as they had for the Spaniards and Indigenous people who lived there 300 years ago.

From my backyard, the sound of the morning bells summoned our family to services at the mission’s church, where each of my four siblings and I were baptized.

At noon, we prayed the Angelus prayer, pausing our recess so we could kneel on the playground at school. Even now, the bells toll for the Angelus at dusk as the cicadas sing away each fading day.

On a good day, Brother Adrian, a resident Franciscan friar in a brown robe, would let us climb the 25 steps (I counted them) up Mission San José’s spiraling bell tower. A tug of the rope swung the clanging bells. If we held on long enough, our feet would lift off the ground.

Brother Adrian, a friar at Mission San José, in the 1970s. Photo by Garry Adams

Today, with the help of technology, the bells keep a steady beat in the life of all four of San Antonio’s missions, where parishioners still attend Mass and celebrate major family events.

To mark the tricentennial of Mission San José this year, a large outdoor mural will be unveiled in October, portraying the lives of past, present, and future generations. The missions are also holding outdoor services and virtual painting and cooking demonstrations featuring art and foods from the mission era.

“The tricentennial celebrates the diversity, art and history of Mission San José,” says Justine Hanrahan, a visual information specialist for the San Antonio Missions National Historical Park, which manages the historic sites. “Its establishment 300 years ago changed San Antonio’s culture forever.”

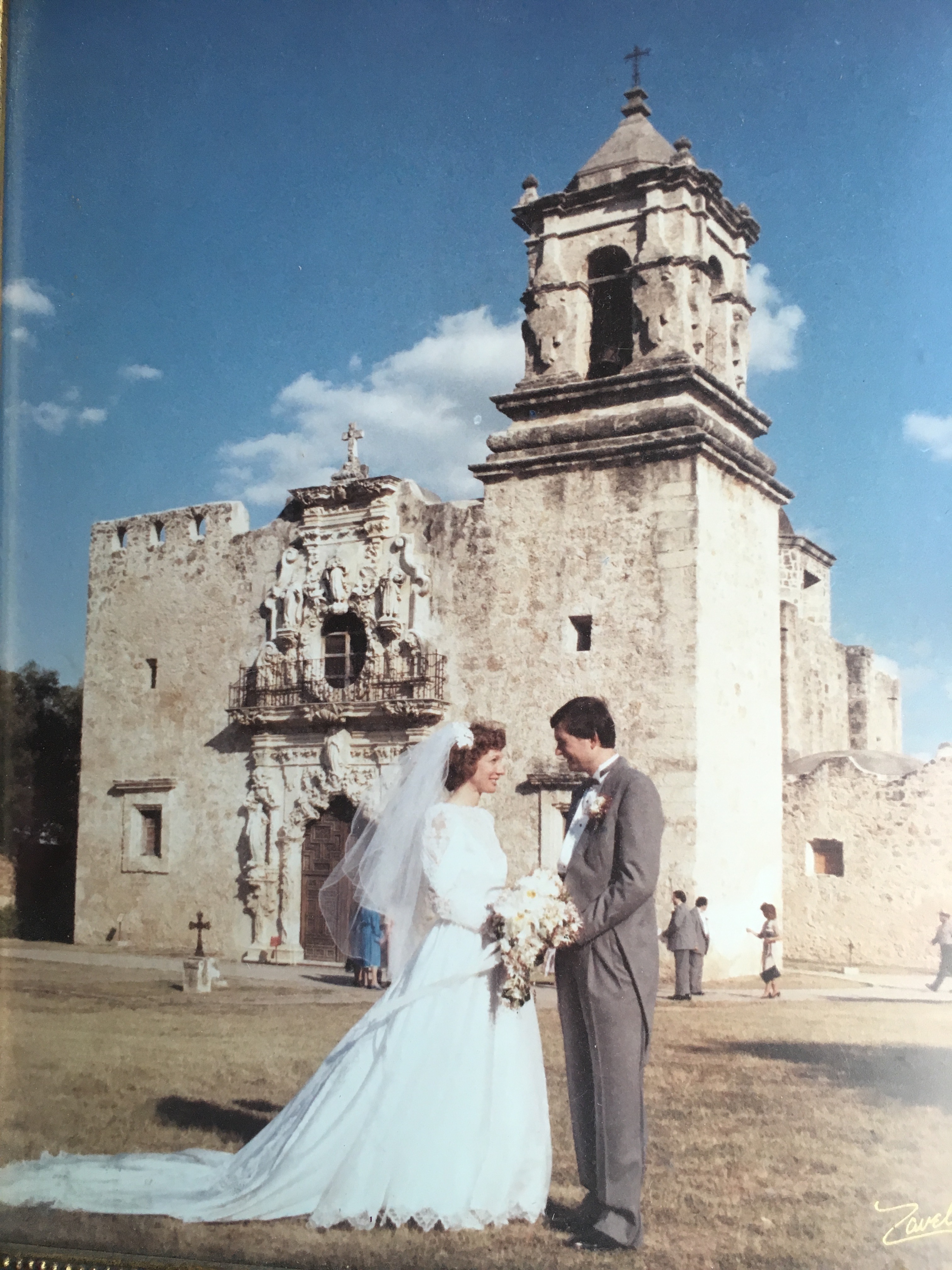

From the day I was born until I moved away in the ’80s, Mission San José was a constant in my life. As a child, I surveyed the night sky from atop a mission wall, scoured wells for coins, and imagined battling warriors from a bastion lookout. When I got married in the mission church in 1988, the day was heralded by a joyful carillon of bells in the cavernous sanctuary. Nearly three decades later, my family processed up the mission’s aisle with the casket of our mother, just as we had done in 1975 with our father, stepping slowly to the cadence of the bell’s somber knell.

Many stories connect neighbors and descendants over the three centuries since the establishment of Mission San José in 1720. Mission San José y San Miguel de Aguayo was established by Fray Antonio Margil de Jesus, two years after the Alamo was established. Missions San Juan, Concepción, and Espada followed a decade later.

Annette Bernhard Nevins and her husband on their wedding day in 1988. Photo courtesy Annette Bernhard Nevins

Spain established the missions as a means of converting more people to Catholicism and to integrate native peoples into the Spanish social structure. Not everyone liked the new rules the Spaniards imposed on the various native tribes of the area. Epidemics diminished populations. Languages were lost. Journals told of trials and triumphs.

During a time when our nation is examining the stories behind our monuments, examining the history of the missions is a necessity.

“It a great time to focus on Mission San José as a diverse part of our heritage,” Hanrahan says.

The artist for Mission San Jose’s tricentennial mural, 34-year-old Sandra Gonzalez, says she hopes her work will highlight the history of Indigenous people and the heritage of their descendants. She plans to brush flower designs in the colors of Mexican textiles onto fabric, and mount the pieces on wood panels on the outside wall of the visitor center at the mission.

The Mexico native and educator, who trained at Pennsylvania’s Academy of Fine Arts, moved to San Antonio just weeks ago to work on the mural while teaching art at Roosevelt High School. Her past work includes a large mural on the Corpus Christi Caller-Times building and another at a hotel in downtown Laredo. The Mission San José mural project is sponsored by the San Antonio non-profit Mission Heritage Partners and Luminaria.

Gonzalez plans to paint an image of an older woman holding a child to represent past and future generations. The design will feature Mission San José’s famed Rose Window, which some say was carved in memory of a lost love by sculptor Pedro Huizar, whose family lives near the missions.

“The Missions are important, and I am very proud to be part of this project,” Gonzalez says.

The organizers hope to attract visitors to the city’s South Side, a historically neglected area that has recently garnered attention with development spurred in part by the popularity of the missions.

“The painting will tie the legacy of the Tejano culture with the city’s modern art culture to help visitors learn about the missions and history of the city,” Hanrahan says.

All mission grounds are open daily, but the smaller Indian quarters, granary, and grist mill remain closed temporarily to the public. Also open is the 15-mile bike-friendly Mission Reach Trail that connects the four missions along the leafy southern banks of the San Antonio River.

On the trail near San Juan, a 5-acre demonstration farm irrigated by a 300-year-old acequia system replicates traditional farming methods of mission inhabitants. In a unique partnership with the National Park Service, the San Antonio Food Bank harvests the 45 acres.

It’s a way the missions continue to give. The bells are keeping tempo with change.

“That’s the beauty of the missions,” Hanrahan says. “Their history and culture live on.”