A 1896 advertisement for condensed milk. Courtesy Boston Public Library, CC BY 2.0, via Wikimedia Commons

It’s a key ingredient in delectable treats ranging from pumpkin and key lime pies to dulce de leche to Thai iced tea, but few people are aware that condensed milk was invented by a man who played a crucial role in the Texas Revolution.

To students of Texas history, Gail Borden Jr. cuts an odd figure, popping up here and there in roles that seem wildly unrelated. He ran the first newspaper in the state; laid out and drew the first maps of Galveston and Houston; then, after disappearing into relative obscurity for a few decades, he returns with the invention of condensed milk.

But not everything the founder of the Borden dairy and Eagle brand empires put his mind to wound up an unqualified success, and it’s the failures that add a little color to his varied career.

A quintessentially 19th-century self-made American tinkerer, Borden was once described as being so haunted by his ideas, his daily appearance when walking the streets of Galveston was like that of Messiah betrayer Judas Iscariot. Rather than rushing around in angst, Borden’s harried demeanor stemmed from him wanting to be at his desk, fleshing out an idea for a new invention.

Born Nov. 9, 1801, in Norwich, New York, the mostly self-educated Borden had learned the trade of land surveying by the time he arrived in Texas in 1829, having put in seven years surveying and teaching school in and around the town of Liberty, Mississippi.

On first arrival here, Borden attempted ranching in Fort Bend County but apparently abandoned that life when Stephen F. Austin appointed him the Texas colony’s first surveyor. As a delegate at the Convention of 1833, he even had a hand in drafting the Constitution of the Republic of Texas.

After six years in the colony, Borden moved to the town of San Felipe de Austin with his brother John and Thomas Baker. They purchased a printing press and started a newspaper that came to be known as the Telegraph & Texas Register, with Borden serving as editor. None of the trio had any experience, so they had to learn to operate the printing press on the fly.

By the time of the paper’s launch in March 1835, revolutionary fervor was growing more and more ardent among the colonists. Borden attempted to be impartial and objective, but became less so as Antonio López de Santa Anna’s army approached and after the slaughter at the Alamo. In the paper’s last issue before a long hiatus, Borden printed the names of the fallen at the Alamo. That grim task done, and with Santa Anna headed their way, the press was disassembled and trundled east in a vain attempt to avoid capture. They got as far as Harrisburg (today, an east Houston neighborhood) before they were caught in the act of printing an issue. The Mexican army soldiers arrested them and tossed the press in Buffalo Bayou.

The Battle of San Jacinto, the last fight of the Texas Revolution, came less than a week later in April 1836. The Borden brothers and Baker were cut loose, but it would not be until August that a new press could be procured and publication resumed, this time in Columbia, the Brazoria County town most people thought would end up the permanent capital of Texas.

On the move again, the trio ended up in the newly declared capital of Houston, where a discouraged Borden sold his interest in the paper in June 1837. Though it had sold well, the paper had costs that far exceeded income. But, as would prove common with Borden, this failure had a silver lining. The newspaper’s archives stand as “an invaluable repository of public documents during this critical period of the state’s history,” according to historian Eugene C. Barker.

Borden found himself surveying again, but this time also making maps. He had a hand in laying out the new cities of Houston and Galveston—but don’t blame him if you’ve ever been half-blinded by the sun heading west during Houston’s evening rush hour. In Borden’s original street plan, no Houston street is angled directly toward either the rising or setting sun. (Subsequent developers ignored his grid and foolishly laid out streets on a strict east-west axis.)

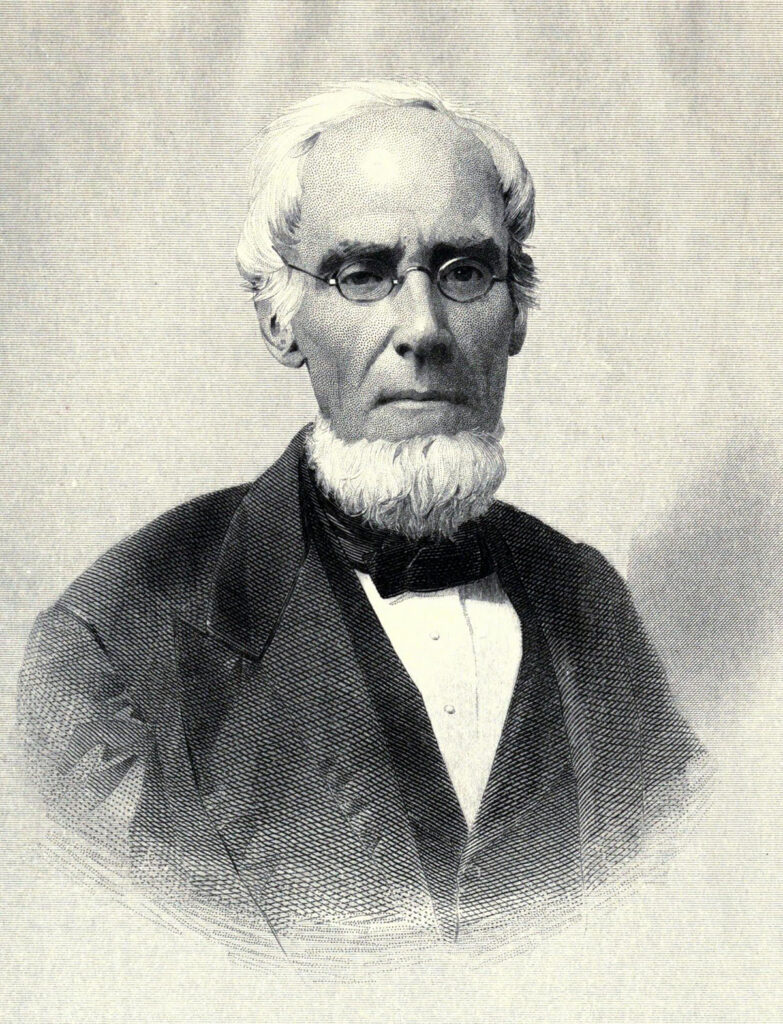

Gail Borden created dairy products, including condensed milk.

His plan for Galveston took a “keep it simple, stupid,” approach, simply laying out a grid that angled across and along the northeast-to-southwest sweep of the barrier island. Around the same time, he was assigned the creation of the very first topographical map of the fledgling republic. This apparently left him plenty of time for side projects, including the invention of the Terraqueous Machine.

Imagine a wagon with a mast and a sail. Now imagine the wagon’s wheels also functioning as propellers when underwater. This was the idea for Borden’s Terraqueous Machine, an early stab at a wind-powered land and amphibious vehicle.

One stiff-breezed day, in front of a throng of laughing seagulls and curious onlookers, Borden and a crew trundled his invention to Galveston beach. On a suitably windy hoist of the mainsail, they were off down the beach toward the east end of the island. Faster and faster whizzed the boat-wagon over the hard-packed sand until it hit the water. The change in surface jolted the human cargo, and the man in control of the sail lost his grip. The Terraqeuous Machine was swamped in the surf, sending everyone overboard. One by one they popped up. “Where’s Borden?” one man asked. “I sincerely hope he has drowned,” another groused, just before the humiliated Borden emerged unharmed from the churning waves.

Sometime around 1849, Borden abandoned modes of transport and zeroed in on dehydrating and condensing food and drinks. First came his “meat biscuits,” or as they were also known, “portable desiccated soup bread.”

“This is one of the most valuable inventions that has ever been brought forward, and will be the means of enabling travelers and mariners to enjoy both vegetable and flesh in a most dainty dish at any moment, and what is better, a traveler may carry a month’s provisions in a small tin case,” he wrote in his 1850 patent claim. “It is now used exclusively by Texan vessels sailing from Galveston.”

Basically bouillon, flour, and water, then baked, the meat biscuit could be eaten whole or made into a soup by crumbling a few in boiling water. A food blogger (who describes herself as a “culinary chronaviatrix”) once recreated the old recipe on the dormant blog Time Travel Kitchen and declared the biscuits enthusiastically “Okay!” The broth got pretty thin, but that was nothing adding more meat biscuits wouldn’t cure, she wrote, concluding, “I can see how this would be a useful addition to wagons heading west.”

For his invention, Borden won the Great Council Award at the London World’s Fair of 1851. But the market was nowhere near as eager, and not even soldiers would eat them, claiming that the meat biscuits did not fill them up and even made them ill. So, after sinking his entire fortune into his meat biscuits dream, he was now without a contract from Uncle Sam. Borden wound up in bankruptcy for his troubles.

But his luck would change—again, he had an idea. On Borden’s return voyage from the London World’s Fair, an epidemic passed through the small herd of cattle that provided milk for the passengers. Even as the cattle were dying, the ship’s crew kept milking them, and soon enough, whatever was ailing the cattle had been passed onto the passengers. Babies wailed for days until several of them died and were buried at sea.

Their cries haunted Borden for the rest of his days and, after moving back to New York, where he hoped to find some way to market his meat biscuits, he simultaneously turned his attention to experimenting with milk. He developed a method to condense it—basically stripping away the water and leaving behind the creamy essence. He also launched a crusade into the lax oversight of the dairy industry, then rife with scandals over routine sales of rotten milk adulterated with substances like formaldehyde.

That would come after he almost went bankrupt again. Condensed milk just seemed odd to people. They were not buying the stuff at the scale Borden needed. Then the Civil War broke out and the U.S. Army declared it good enough for their men, who over time, adapted to it and even came to prefer it.

As Borden’s company grew, he exerted more and more control over dairy farmers, eventually developing a Borden “Ten Commandments” of dairy hygiene the farmers had to adhere to in order to do business with the company. (Bear in mind this was decades before Upton Sinclair and other early stirrings of large-scale food safety movements.)

After finally hitting the jackpot, Borden returned to live out his days in Texas. He and one of his brothers and some of their children set up a sort of family compound they named after themselves in Colorado County, a few miles northeast of Weimar, where he tinkered with condensing other items, like coffee, tea, fruit concentrate, and cocoa, though never quite achieving the success he found with milk. He died in 1874 and his body was shipped, by private rail car, back to New York, where today he rests in Woodlawn Cemetery in the Bronx under a tombstone reading:

“I tried and I failed. I tried again and again and succeeded.”

Now that is the epitaph of a happy man.