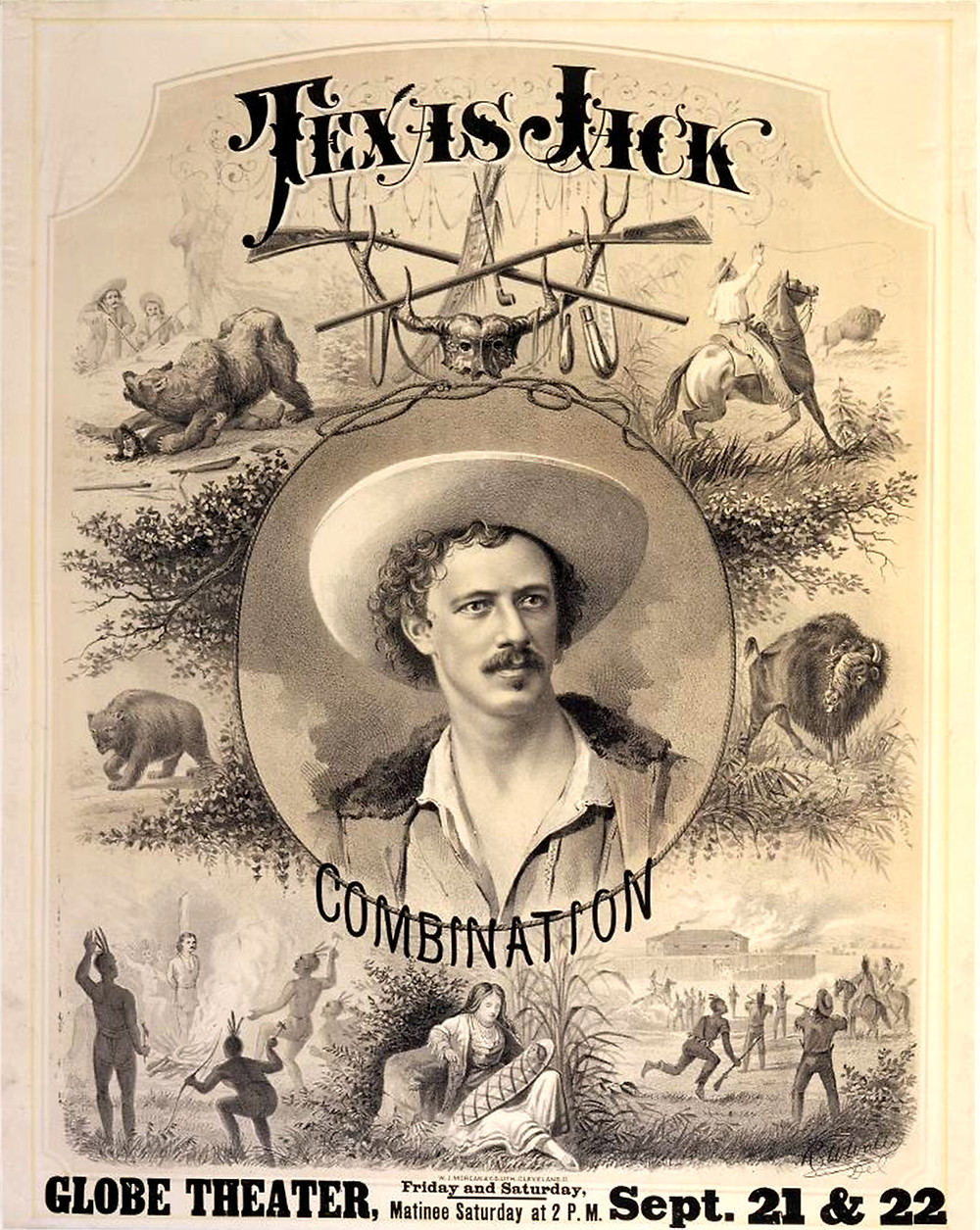

Texas Jack performed in shows with Buffalo Bill Cody and Wild Bill Hickok. Poster courtesy of Matthew Kerns.

Like thousands of other Texas pioneers, Virginia native John B. Omohundro headed for the Lone Star State after the Civil War, in which he had served as a Confederate scout. He worked as a cook for the Sam Allen Ranch on Buffalo Bayou and as a cowboy on John Taylor’s Bexar County spread, spending about three years living in the state. After leading a cattle drive to Tennessee, Omohundro was dubbed “Texas Jack” by residents of the Volunteer State. The name stuck, making the Virginian a willing ambassador for the sprawling realm between the Red River and the Rio Grande through the rest of his short but thrilling Wild West life and career.

A new biography, Texas Jack: America’s First Cowboy Star by Matthew Kerns, tracks Omohundro’s days as a schoolteacher, cowboy, scout, hunting guide, frontier thespian, and one-half of a pioneer power couple after his 1873 marriage to Italian-born prima ballerina (and occasional actress and operetta diva) Giuseppina Morlacchi. If you’re feeling inspired, a Fredericksburg shop named in his honor, Texas Jack Wild West Outfitters, offers reenactors and other Old West buffs the chance to dude up in Texas Jack-style duds and to tote weaponry inspired by Texas Jack’s own.

Kerns, a digital archivist and historian in Chattanooga, Tennessee, who runs the Western history website Dime Library, got interested in the Texas Jack story after hearing about the pioneer drama Scouts of the Plains. “If you were looking for entertainment back in 1873 or 1874, you could go down to your local theater and pay a quarter or so to see a play starring Buffalo Bill Cody, Wild Bill Hickok, and Texas Jack Omohundro,” he says. “I knew about those other two—I think most Americans with an even passing interest in the West do—but I hadn’t ever heard of Texas Jack Omohundro.”

Kerns got his hands on a copy of the sole biography of Omohundro, Herschel Logan’s 1954 volume entitled Buckskin and Satin, and then began investigating further. “I soon determined that there was a lot to Mr. Omohundro that hadn’t ever been recorded,” he says. “Eventually, I realized that because of the impact Texas Jack had on the early depictions of the West, and on his best friend and partner Buffalo Bill Cody, he was the first cowboy to make an impact and to lay the foundation of the fictionalized version of the kind of cowboy in fiction and film that battles native warriors, lives a life of adventure, and exemplifies a certain kind of aspirational figure in American media.”

Fast friends since they first met in 1869, Buffalo Bill and the Texas cowboy hunted, scouted, and drank together. Omohundro even helped wallpaper Cody’s North Platte, Nebraska, home. Kerns found Department of War correspondence and period newspaper accounts describing an 1872 Nebraska skirmish with Miniconjou horse raiders. Texas Jack reportedly shot and killed a raider just as he was taking aim at Cody. “Finding a moment where Texas Jack saved the life of the great showman who would spend a career turning the humble job of cowboy into the pinnacle of American heroism really shines a light on the kind of impact Texas Jack would have,” Kerns adds.

Fast friends since they first met in 1869, Buffalo Bill and the Texas cowboy hunted, scouted, and drank together. Omohundro even helped wallpaper Cody’s North Platte, Nebraska, home. Kerns found Department of War correspondence and period newspaper accounts describing an 1872 Nebraska skirmish with Miniconjou horse raiders. Texas Jack reportedly shot and killed a raider just as he was taking aim at Cody. “Finding a moment where Texas Jack saved the life of the great showman who would spend a career turning the humble job of cowboy into the pinnacle of American heroism really shines a light on the kind of impact Texas Jack would have,” Kerns adds.

Starting in 1873, the two friends appeared in over 550 performances of Life on the Border, The Scouts of the Plains, and other frontier dramas. They toured with the plays from Maine to Texas. A critic for the Galveston Daily News noted that the thunderous applause for an 1875 troupe headed by Buffalo Bill, Texas Jack, and his wife could be heard a mile from the Tremont Opera House (located on Market Street, it became the E.S. Levy Building and has been renovated for artist lofts).

When the artists moved to the Houston Opera House, a newspaper in that city called The Age noted that the “Peerless Morlacchi’s” contribution to the bill consisted of a cavatina from the opera Ernani and the dramatic assumption of “four different characters.” Of the theatrical diversion presented by her husband and his fellow actors, The Age wrote, “One can now get a taste of wild life on the border without participating in the danger.”

Biographer Kerns adds that he found Omohundro to be something of a showbiz trendsetter during his four remaining years of continued trouping (before his death in 1880) after splitting the boards with Buffalo Bill. “He brought along Donald McKay, a Warm Springs scout who had risen to fame during the Modoc War, years before Cody added any famous Native Americans like Iron Tail or Sitting Bull to his show,” Kerns explains. “Jack did a series of shooting and trick-riding exhibitions on the East Coast with Doctor Carver, the famous rifle shot, five years before Buffalo Bill and Doc Carver teamed up to launch the Wild West show in 1883. And Jack set up a Western-themed hotel with a saloon and shooting gallery outside the Philadelphia Centennial in 1876, predating Cody’s famous stand with the Wild West at the Chicago Columbian Exposition by 17 years.”

Kerns also offers the view that Texas Jack was the first to perform cowboy trick roping on the stage, and a young showman who called himself Texas Jack Jr. reportedly inspired Will Rogers’ lasso act. Years earlier, Omohundro had rescued the future showman from a Comanche raiding party and delivered him to a Fort Worth orphanage. (It’s unclear if Texas Jack Jr. was the adopted son of the couple.)

When he died of tuberculosis and pneumonia, Texas Jack was not yet 34 years old. “That wasn’t the kind of death that lingered in popular culture like his friend Wild Bill’s death at the hands of an assassin in Deadwood,” Kerns says. “Had Texas Jack either ‘died with his boots on’ like Wild Bill or lived to solidify himself as central to the story of the American West like Buffalo Bill, I think he would be just as well remembered as those men, with museums, films, and books enlarging the legend over time.”

He’s certainly remembered in Fredericksburg, where the logo for Texas Jack Wild West Outfitters includes Omohundro’s likeness. “My dad, Mike Harvey, who started the business in Houston in 1984 and moved it to Fredericksburg in the mid-1990s, is a big fan of Texas Jack,” says Jamie Wayt, who inherited the business from her late mother, Mary Lou Harvey, and runs it with her rock ’n’ roll guitarist husband Bryce Wayt. Mike Harvey’s Omohundro private collection includes an original Texas Jack/Buffalo Bill playbill poster from a Chicago theater, an ivory cane signed by fellow cast members, and Texas Jack’s own 1870 Smith & Wesson pistol. Harvey’s Cimarron Firearms company produced and markets an authentic replica of the firearm.

Jamie describes Texas Jack as “one-stop shopping for all things Old West.” Reenactors and frontier fashionistas alike will find head-to-toe period clothing, as well as modern Western wear and gear from Stetson, Roper, Wrangler, El Paso Saddleblanket, and more. Ten-foot-tall blow-ups of photographs of Texas Jack, Buffalo Bill, and other troupers of the stage adorn the walls of the store, which is housed in a former blacksmith shop built in the late 1800s. Bryce declares it “the greatest Western store on earth,” adding, “I imagine ol’ Texas Jack himself would feel right at home.”

According to Kerns, there has been great interest in the Texas Jack story among readers in the Lone Star State, many of whom have ordered signed copies from his Dime Library website. “Just last week I sent a copy to a descendent of Moses Austin,” he says. “While Texas Jack’s story isn’t strictly Texas history—he was born in Virginia, scouted in Nebraska, taught school in Florida, spent a lot of his time exploring Wyoming, and died in Colorado—his time in Texas as a trail-driving cowboy was so formative that he proudly carried the name and symbols of Texas with him for the rest of his long career. … And it’s good to know that readers of Texas haven’t forgotten Texas Jack.”