Down

in

San

Leon

Who needs frills when you’ve got character?

By John Nova Lomax

The Sunday afternoon scene in the San Leon Beach Pub is even more laid-back and mellow than it is on most Sabbath days.

“The jam session’s canceled this week,” says the blonde 40-something bartender. “That’s ’cause we had three last weekend—Steve-O’s memorial benefit, the biker run, and the regular one. Everybody’s recoverin’.”

Still, about a half-dozen 60-something men puff on Marlboros and Pall Malls and nurse cold beers and bloody Marys around the horseshoe-shaped bar on a sunny day this February. The burning issue of the moment: How to fix the bar’s water heater? One of the ad hoc plumbers surmises that the appliance’s nipple might be awry. “It’s always the nipple,” one of the drinkers sighs, staring up into a cloud of blue smoke.

A mix ranging from Conway Twitty’s “Hello Darlin’” to Pink Floyd’s “The Great Gig in the Sky” burbles from the jukebox as “Gator” Miller, one of the approximately 5,000 philosophers who call this unincorporated community on Galveston Bay home, holds forth over a koozie-wrapped bottle of Miller High Life.

Photo: Rick Dunlap

A colorful sign on a San Leon beach. Photo: Kathy Adams Clark.

“If you want to go to a tourist trap, Kemah and Galveston are right up the road,” he tells me, his long, curly black hair spilling from under a ball cap reading, “U.S. Navy, Retired.” “But if you want a taste of the real, come on down to San Leon.”

Indeed, San Leon is that. Located on a stubby peninsula about 40 miles southeast of Houston, there’s a timeless quality to its spacious, palm-lined backstreets. A slapdash assortment of dwellings occupy the large lots, from the occasional McMansion to classic stilted beach houses, and on down to trailers that look like tin cans. Ostentation is in short supply in this community.

“Community” is the key word here, in both the literal and the general sense. Scarcely a weekend goes by without a benefit for somebody’s burial expenses or medical bills, a toy-donation event, or a scholarship soiree. In a mirror image of the movers and shakers of big-city enclaves like River Oaks and Highland Park, San Leon residents love to party for a cause, even if their charity events are seldom gushed over in glossy society magazines.

And San Leon is a community in the sense that, time and time again, locals have overwhelmingly rejected efforts to incorporate or merge with neighboring Bacliff. Such a step would possibly lead to a level of “progress” that could cause “Kemahfication” or “Houstonization”—both prospects anathema to the likes of Gator.

Incorporation reeks of a money-grubbing officialdom San Leon operates quite nicely without. “Leave us out of your rat race,” says Gator, publisher of the Seabreeze News, the town’s monthly newspaper. “Houston and Dallas—these are actual places, and we know that they are necessary. But please leave us out of it. We don’t want to participate in all that, and we don’t want that coming this way.”

It hasn’t, not yet. A Dollar General is the only chain business in town, though word is a Papa John’s is coming. Bryan Caswell, a renowned Houston chef and San Leon fan, visits to go fishing and buy chickens at SeaBreeze Hens, a business that hatches and raises dozens of varieties of poultry.

“There are very few places left that are just hanging on the edge of the world,” Caswell says. “Nobody’s checking on them; they do what they want to do. And that’s a beautiful thing. Nobody’s trying to gentrify anything, nobody’s trying to raise property values. They’re just living, man, and enjoying themselves, and there’s not enough of that left in the world.”

“There are very few places left that are just hanging on the edge of the world.”

Ask a Houstonian if they’ve been to San Leon, and chances are high they will tell you they have not. But ask them if they have been to Gilhooley’s, the ramshackle oyster palace famed for its chargrilled bivalves, or Topwater Grill, a bay-side retreat on April Fool Point, and chances are much higher that they will say they have. They just don’t realize these temples of Texas Gulf Coast seafood are in a place called San Leon.

“Nobody gets here by mistake,” Gator says. “Nobody is just passing through, because San Leon ain’t on the way to nowhere.”

San Leon has gone through a few hurricane-enforced makeovers in the course of its 200-odd years of European settlement. After a townsite called San Leon failed to thrive in the Texas Republic days, a consortium of investors renamed the place North Galveston during a brief industrial boom in the 1890s. The investors built a railroad from the island—through North Galveston and up to the Great Plains, bypassing Houston—as part of a scheme to ensure Galveston’s future as Texas’ preeminent seaport.

The plan was a hit at the World’s Columbian Exposition of 1893 in Chicago. Hopeful Midwestern settlers streamed south by the trainload. At one time North Galveston was home to an estimated 2,000 people, along with warehouses, brick kilns, a cigar-rolling house, sawmills and lumber yards, a railway depot, and a 75-room three-story hotel.

Then came the Great Storm of 1900. Goodbye North Galveston, and hello San Leon, born again under its old name, never to dream again on a scale quite so grand or industrious.

Since then, several more storms have ravaged San Leon—most recently Hurricane Ike in 2008—but each time it has come back to life very much as it was the day before landfall. Locals will tell you the loss of their homes is just “the price you have to pay to live in paradise” as they slowly rebuild.

When the coronavirus pandemic closed churches and bars and put a kibosh on community benefit parties, San Leonians turned their energies inward. “All of a sudden people are cleaning up their properties, planting flowers, mowing the grass, and sprucing things up nicely,” Gator reported in a follow-up call in April.

Melinda Conner, the owner of SeaBreeze Hens, represents the old-fashioned drive and blue-collar ambition it takes to prosper in a town that prefers to reside off the map. She grew up on a Washington state cattle ranch but found her calling in the chicken business. “There are no deed restrictions because we are unincorporated,” Conner says. “You can do what you want out here.”

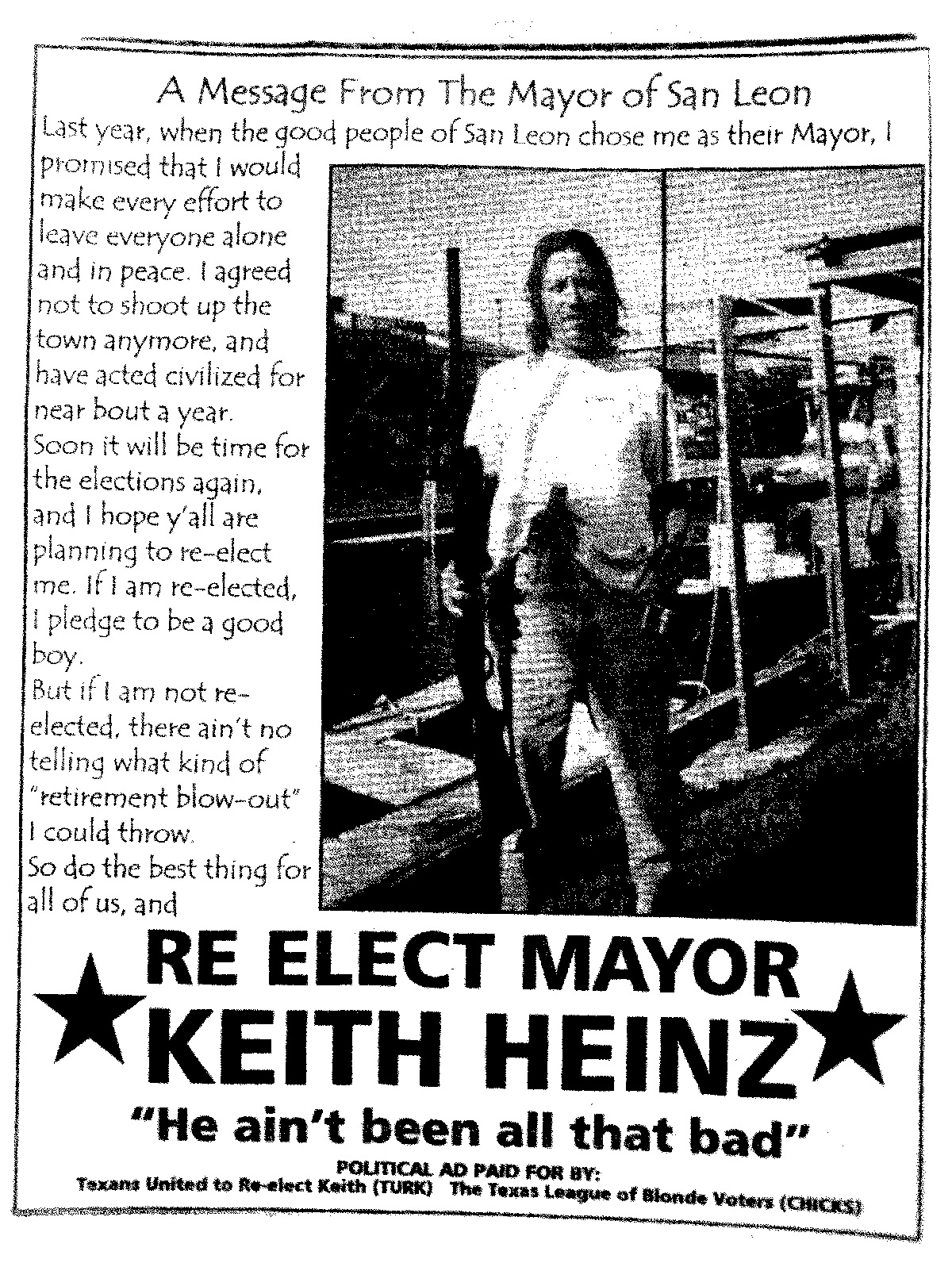

“If San Leon was a country, the criminal code would consist of just one law, and that would be ‘Don’t disturb the peace.’”

In many ways, San Leon has reverted back to one of its earliest iterations as a pirate camp, circa 1820, when the smuggler Jean Lafitte made San Leon’s Eagle Point a satellite of his Galveston headquarters.

Such lore inspired the name of the Buccaneer Bar, where one night in 2005, Kelly and Matthew Railean, a young Houston couple, spent an evening sampling rums they had collected on trips. Emboldened by the booze, they decided they could do better with their own rum distillery, and in 2007 they opened Railean Distillery right there on Eagle Point, smack-dab on the site of Lafitte’s old pirate camp.

“We got into rum because of sailing,” says Kelly, a former beverage wholesaler and trained sommelier. “And that led us also to pirates. Just that whole atmosphere—the history of rum, everything.”

Hurricane Ike ravaged the Raileans’ distillery in 2008, but the couple rebuilt and added a tasting room. Today you can hoist your ration of Railean’s grog amid Jolly Roger-themed surroundings, including a pirate eye chart. (Every letter is arrrrrrrr.)

But San Leon’s pirate vibe goes even deeper than those surface accoutrements. It’s in the cultural DNA of San Leon, in the resolutely egalitarian and libertarian mindset of the area. The Upper Texas Coast is about as laissez faire as it gets: San Leon was part of the congressional district that sent Ron Paul to Washington for 16 straight years, five of them after he voted against $23 billion in federal relief when Hurricane Ike utterly devastated the community.

“If San Leon was a country, the criminal code would consist of just one law,” Gator says, “and that would be ‘Don’t disturb the peace.’ As long as you don’t disturb the peace you can do whatever the hell you want to do.”

A sculpture of carousel horses in San Leon. Photo by Kathy Adams Clark.

Corporate America is leery of the whole peninsula thanks to its many tangled real estate titles, Gator says. Decades ago, according to local lore, a regional newspaper handed out lots as prizes in subscriber-only raffles. “Then when you canceled the subscription they didn’t take it out of your name, but they gave the same land to the next guy,” he says. “And so eventually the tax collector said, ‘Whoever last paid taxes on this is the landowner.’”

While those complications seldom arise in the normal course of San Leon life, they have kept big-box retailers at bay. What San Leon has instead of chain retailers are healthy surpluses of fishing piers and honey holes, boat launches, boat-to-table seafood restaurants, and dive bars. Lots and lots of dive bars: 17 at one recent count, compared to two churches and a small Buddhist temple servicing the insular Vietnamese shrimper community.

These dive bars are not the dive-themed bars ensconced in the irony of youth that you find in big cities. The Beach Pub and other San Leon bars are the real deal. The mere fact that you can still smoke inside would qualify them, but they meet the mark by other measures as well: wood-paneled interiors dark even at noon (and often open before then each day); cheap ice-cold beer and stiff well drinks (none served frozen); a slow cooker simmering in the corner with a complimentary stew; and a barmaid who calls you “hon” when she takes your order.

Above all else, a San Leon bar must not take on airs. San Leon folk won’t have it any other way. Gator has seen many a bar with greater pretensions come and go. “That’s why this place looks like a dive, and Gilhooley’s looks like a dive,” he says. “People who live here love that because they’re unpretentious.”

In April, Gator said he expected San Leon’s ragged-but-right hospitality industry to emerge intact from the coronavirus quarantine because its establishments don’t face the same high overhead costs that have capsized some of their big-city counterparts.

The Beach Pub’s bar door opens to blinding sunlight, and in walks a young woman in a faded blue sundress and flip flops. “Brittle for sale! Would any of y’all like some homemade brittle?” While she found no takers for her confections, she walked out smiling, headed for the next target on her Sunday route.

“Everybody here tries to find a gig so they don’t have to commute,” Gator explains.

You see it all around in San Leon, once you learn to look for it. It’s a place on the make, literally, a place where people catch, build, raise, operate, and repair actual things; very little of San Leon life or livelihood is in the abstract. Consider the shrimp and oyster boats out in the bay, the rum distillery on Fifth Street, and the chicken coops on 12th Street. Here’s somebody upholstering furniture out of their home; there’s another peddling backyard-smoked brisket.

But San Leon is not all hand-to-mouth, paycheck-to-paycheck. Railean Distillery is a midsize success story. Another is SeaBreeze Hens, whose array of live yardbirds draws customers from as far away as New Orleans.

“They’ve got the best variety in the state,” says Caswell, the Houston chef. “They’ve got heritage breeds, all sorts of things, and it’s right in the middle of San Leon. Just a few lots with nothing but chicken hutches.”

When you delve into the histories of San Leon’s more prominent institutions, you start to think there’s a Hollywood movie behind each one of them. It’s the inspirational stories of the American dream achieved San Leon-style, against long odds, that are most easily found. The Vietnamese fisherfolk who escaped their communist homeland by boat in the 1970s embody this story. Many of their children eventually move away, pursuing the next chapter of the dream. There are similar tales behind Topwater Grill, Misho’s Oyster Company, and Prestige Oysters, three of the town’s top employers.

As a child, Walter “Captain Wally” Jakubas, Topwater’s Poland-born patriarch, and his family were taken prisoner by the Red Army. The family escaped, and Captain Wally’s long, picaresque road to San Leon first passed through the Russian Far East, Persia, India, British Colonial Africa, England, Chicago, and Houston.

Wartime strife in the Balkans gave rise to San Leon’s thriving oyster industry via the intertwining tales of Misho Ivic and Johnny Halili.

Ivic fled Yugoslavia after obtaining his degree in mechanical engineering. In 1972, he found himself in America at the age of 22, an overeducated deckhand on a Louisiana oyster boat. He bought a boat and within five years purchased an oyster lease. Today Misho’s Oyster Company is one of the top three shippers and processors of oysters in Texas, along with Halili, an emigre from Stalinist Albania.

Halili’s American journey began in the Chicago projects. A cousin summoned him to a better job on an oyster boat, one that turned out to be captained by none other than Ivic, who became Halili’s mentor.

Today, Ivic also owns Gilhooley’s, while Halili’s Prestige Oysters has plants in San Leon and Louisiana that process oysters from 100 boats ranging from South Texas to the Chesapeake Bay. Prestige recently became the first oyster fishery in the Americas to be certified by the international Marine Stewardship Council for its environmental sustainability.

Staci Davis, a Houston chef, came to San Leon to regroup after her popular Radical Eats restaurant fell victim to rent hikes in Houston’s Montrose neighborhood. She spent some time cooking at Topwater and says she has periodically thought about writing a newcomer’s guide to San Leon.

“Probably even before you move there, you should learn to skin and clean a fish because within two weeks of moving to town, somebody’s gonna offer you a fish,” she says. “And you will keep getting fish as long as you live there. Two, one of the first things you should do is find some way to screw up spectacularly. That’s your calling card. Get people talking in the bars about you—no matter how bad it is, pretty much everyone in there has done just as bad or worse. They won’t judge you for it. It’s just your way of joining the club.”

As her advice illustrates, San Leon is a state of mind apart from the rest of us.

“Not only is this not Houston, but it’s barely Texas,” Gator says. “Cowboy boots and big belt buckles? That’s not what they wear in San Leon. It’s an island kind of atmosphere, but it’s not a Key West atmosphere. It’s an island-on-a-budget

atmosphere. Neckties and high-heeled shoes don’t sell here.”

Gilhooley’s Restaurant and Oyster Bar,

222 Ninth St. 281-339-3813;

gilhooleystx.com

Topwater Grill (and bait house),

815 Ave. O. 281-339-1232;

topwatergrill.com

Railean Distillers,

341 Fifth St. 713-545-2742;

railean.com

SeaBreeze Hens,

831 12th St. 281-900-0183;

seabreezehens.com

San Leon Beach Pub,

222 First St. 281-559-4202

San Leon Oysterfest,

held annually in April, features an oyster cookoff, an oyster-eating contest, and live bands. The event raises funds for the protection of Galveston Bay oyster reefs.

sanleonoysterfest.com