(Illustration by Katie Vernon)

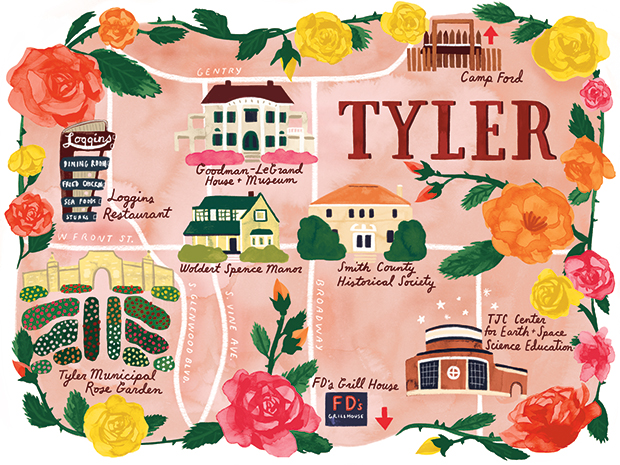

The 84th Annual Texas Rose festival runs Oct. 19-22 at the Tyler Municipal Rose Garden, 420 Rose Park Drive, Tyler.

Mike and Barbara Downs are the first two I meet. A little background: Their life sounds like the premise of a hit television show. A retired Army colonel and his New York-born wife, both working in the stressful whirl of Washington, D.C., decide to move south to operate a bed-and-breakfast in a historic Tyler home.

The Downs’ 1859 Woldert-Spence Manor, built by one of Tyler’s leading families, sits on a quiet street near downtown. Guest rooms are named for the family members who once occupied them.

I check in to the Robert Spence Jr. room, and after a restful night’s sleep, come downstairs to find a breakfast menu of orange cranberry muffins with fruit and yogurt, followed by stuffed French toast with bacon on the side. While waiting to be called to the table, I browse the manor’s book and magazine collection in the parlor and visit with the other guests—a family up from Houston for their daughter’s wedding.

Iconic Festivals

After breakfast, we all disperse to our plans for the day. My tour of Tyler begins in the past, on the balcony off my room, which overlooks the brick veneer of South Vine Avenue. It’s a relaxing place to read the work of Alma Woldert-Spence, the mother of my room’s namesake and an acclaimed Texas poet. In her 1936 book Silver Doors, she wrote of a seminal period in Tyler history, when nearby towns grew “with incredible rapidity, overnight, for they awakened to find themselves in the heart of the world’s greatest oil field. As sprang the genie from the vase, in tales told on Arabian nights, so springs from the depths of the earth the flowing gold, the genie of the twentieth century.”

That genie appeared during the Great Depression and granted Tyler the wish of having the benefits of oil without the drawbacks. As gushers blackened the sky in places like Kilgore, Tyler handled the money as the corporate and banking center of the boom, raising flowers instead of derricks. In 1952, the city opened the 14-acre Tyler Municipal Rose Garden. Today it is filled with 32,000 bushes of every color of rose imaginable. I take a minute to relax on one of the benches and savor the view—a sun-dappled pond, tree-shaded walkways, and purling fountains.

Inside the adjacent Tyler Rose Museum and Gift Shop, exhibits recall the history of Tyler’s rose industry, which goes back even further than oil. The area’s earliest European inhabitants recognized its ideal soil and climate for fruit trees, particularly peaches. But after a disease swept through in the late 1800s, commercial growers began switching to roses, which were equally suited to the area.

The museum also exhibits memorabilia of the annual Texas Rose Festival. This four-day event, held in October, celebrates the iconic bloom and also the civic spirit of Tyler. Involvement in the festival is a family tradition for many. Young boys and girls serve as royal attendants. Over the years, sons progress to escorts, daughters to duchesses or ladies in waiting, with one chosen as queen each year.

Rivaling the Rose Festival in importance is Tyler’s Azalea and Spring Flower Trail, begun in 1960 and held each year across three weekends in late March to early April. The heart of the festivities is a 10-mile circuit of buildings and gardens whose landscapes nature—with a little human help—has painted with blooming azaleas, dogwoods, tulips, and other flowers.

One of the most impressive buildings on the trail is the Goodman-LeGrand House & Museum. When Sallie Goodman-LeGrand donated this mansion and its grounds to the city in 1939 as a park and museum, she included family furnishings, artwork, and a good deal of clothing. That means you can see the various rooms much as they were once lived in, along with items such as fine china, antique musical instruments, and 19th-century medical books. Museum Curator Mary Foster and her staff also try to keep the home “alive” by making it available for private functions, such as bridal showers and weddings, and have even hosted murder-mystery dinners.

The Tyler Municipal Rose Garden;

Living history

The Tyler Municipal Rose Garden;

In a former Carnegie Library a few blocks over, the Smith County His-torical Society showcases dynamic exhibits on county history, grouped chronologically, beginning with the Caddo Indians and extending through the oil boom to modern times.

“We want to do more than display historic artifacts, we want to help interpret the past,” the society’s office manager Savannah Cortes tells me. She likes visitors to find something new on each visit. Currently in the works is a World War I exhibit, scheduled to open Nov. 11 for Veterans Day.

The society also manages Camp Ford Historic Park—a Civil War POW stockade at the edge of town. On the way there I stop for lunch at a Tyler restaurant—Loggins—that is pretty historic itself. It’s been around since 1949.

“It started out with six stools, two tables, and carhop service,” says owner Jerry Loggins, who took over from his father in 1985. He runs the restaurant, now open for lunch only, with his wife, Lyana. The dining room has ex-panded from the early days, and when you enter you may notice photos on the wall of Johnny Manziel—the Texas A&M quarterback who won the Heisman Trophy in 2012. Jerry and Lyana are longtime Aggie football fans, but they also happen to be Manziel’s grandparents.

That’s a little ironic, because unlike the daredevil style of “Johnny Football,” the playbook at Loggins is decidedly conservative. Nothing fancy here, just good homestyle cooking and plenty of it. The buffet offers choices like chicken-fried steak and chicken and dumplings. And one taste of the chocolate pudding with its sticky, cloud-like meringue topping may take you back to your grandmother’s kitchen.

Heading northeast on US 271, I pull into the dirt parking lot of Camp Ford. The largest Confederate-run prison camp west of the Mississippi River, it held over 5,300 prisoners in July 1864.

Life for the prisoners was as threadbare as their uniforms. But today, visitors need abandon no hope as they enter the log gates. Instead of the squalor of a multiacre prison encampment, there are informative signs, a quiet walking trail, and replica living quarters—from makeshift tents to tiny “shebangs” the prisoners built of logs. Glancing inside one, I wonder what life was like for prisoners among

all the dirt and bugs and disease that once held sway. How many POWs lay awake at night, thinking of homes far away, nothing beautiful to look at but stars?

Travel to the Heavens

The night sky is one thing that would have been better back in the 1800s. As the sun sets, I find that modern Tyler’s city lights dim the view. But my next stop, Tyler Junior College (TJC), has an antidote. The school’s Center for Earth and Space Science Education boasts a state-of-the-art planetarium.

Inside the domed theater, blue carpet and polished wood give the feel of a new suburban mega-cinema. Visitors relax in comfortable chairs as a 40-foot screen takes them across the galaxy, under the sea, or even back in time to watch dinosaurs. And the first Saturday of the month, the planetarium hosts a “star party,” with a traditional night-sky cinema show followed by a telescope viewing of the real thing in the courtyard outside.

With suppertime fast approaching, I hop over to Broadway, which runs north-south through Tyler like an axis. Along it, every kind of eatery imaginable lights up the night. I stop by the relatively new FD’s Grill House, having read favorable reviews of its affordable, eclectic American fare.

Service is hyper-friendly. I order the cedar-planked salmon. The filet arrives well cooked, fork-tender and moist, wearing a crush of pineapple salsa like a crown. A silver shot glass filled with bourbon glaze stands at the side for dipping. The flavors mix beautifully, broken up by bites of a creamy baked potato and tender-crisp mixed vegetables on the side.

As I finish, owner Scott Williams appears from the kitchen, a neatly trimmed beard framing his face.

With the look of a man who enjoys his work, he sits down and reminisces about family outings to Houston’s Restaurant in Dallas when he was a kid. It inspired him to enter the business.

“I wanted to bring to Tyler an exceptional restaurant with a casual yet elegant atmosphere,” Williams says. With a family of his own now, he doesn’t see himself leaving the area any time soon and has ideas for another restaurant or two he’d like to open. If they measure up to FD’s, Tyler not only has something to be proud of, but also more to look forward to.

Heading back to the Woldert-Spence Manor after the busy day, it occurs to me that might make a pretty good slogan for the city overall.