Dedicated road-trippers know that the greatest journeys enrich their final destinations—and sometimes even eclipse them. Famous sightseers from Robert Louis Stevenson to Jack Kerouac and Clark Griswold have shown us how an expedition’s pleasures and pitfalls make the entire experience all the more memorable.

Dedicated road-trippers know that the greatest journeys enrich their final destinations—and sometimes even eclipse them. Famous sightseers from Robert Louis Stevenson to Jack Kerouac and Clark Griswold have shown us how an expedition’s pleasures and pitfalls make the entire experience all the more memorable.

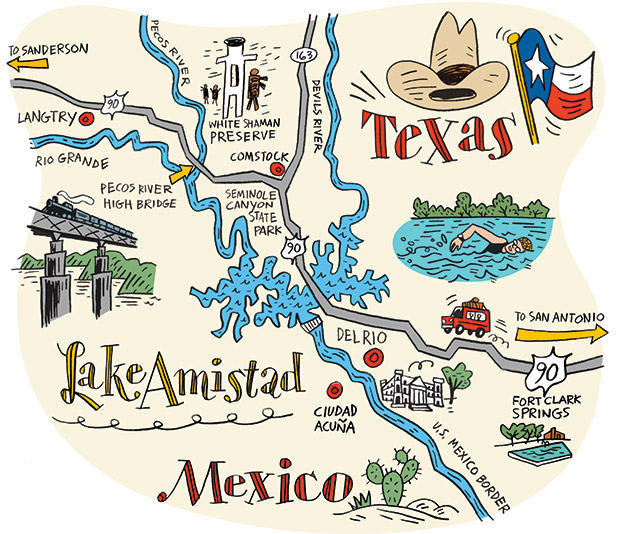

US 90 Destinations

Fort Clark Springs, Call 830/563-2493.

Whitehead Memorial Museum, Del Rio. Call 830/774-7568.

Amistad National Recreation Area, Call 830/775-7491.

Seminole Canyon State Park, Call 432/292-4464; .

The Rock Art Foundation, Call 210/525-9907.

Judge Roy Bean Visitor Center, Langtry, Call 432/291-3340.

Terrell County Visitors Center, Sanderson, Call 432/345-2324.

Terrell County Memorial Museum, Call 432/345-2936.

The Snake House at the Outback Oasis Motel, Call 432/345-2850.

In Texas, the Big Bend region is a common inspiration for lengthy highway hauls, attracting far-flung visitors with desert mountains, borderland atmosphere, and curious small towns. There are several westward routes to Big Bend, but in search of a great road trip, we set out to explore one in particular: US Highway 90, focusing on the stretch from Brackettville to Sanderson.

US 90 traverses the prickly, sunbaked hills of Southwest Texas, crossing box canyons and dry creek beds as it links the occasional town, Border Patrol checkpoint, and roadside attraction. Though it may appear desolate at first, there’s a rare beauty to this rugged countryside, which has supported human life since the end of the last ice age.

“It would have been a very hard life, but the native people clearly made it work for them,” says Jack G. Johnson, park archeologist for Amistad National Recreation Area. “There are numerous seeps and springs in this area, in addition to the Rio Grande, the Pecos River, and the Devils River all converging here. We also have three ecological regions all coming together.”

US 90 navigates this scenery, skirting the Edwards Plateau as it flattens into the South Texas brushlands and then tracing the Rio Grande across Lake Amistad and into the Chihuahuan Desert. Along the way, roadside museums illustrate the region’s borderland history and culture, and a series of springs and rivers provides recreational oases for swimming, hiking, camping, and boating.

Harried travelers might overlook US 90 in favor of speedy interstate highways, but this route provides an adventure in its own right, one that sets the historical, cultural, and environmental stage for the Big Bend and points west. You won’t regret tacking a couple of extra days onto your itinerary. The proof is in the journey.

Fort Clark Springs

Located about 125 miles west of San Antonio, Fort Clark Springs grew up around Las Moras Spring. In the 1800s, Comanches camped at the spring along one of their raiding trails. The Army saw its strategic value and in 1852 claimed the site for a post, in large part to protect the stagecoach roads to El Paso—the predecessors of US 90.

The Army deactivated the post in 1946, and these days, Fort Clark Springs is a 2,700-acre resort and residential community with a motel (set in a renovated barracks), restaurant, golf course, RV park, hiking trails, and dozens of beautiful old limestone-and-wood buildings (all included in a walking-tour brochure). Don’t miss the chance for a swim in the spring-fed swimming pool, which is surrounded by a verdant park of live oak, pecan, cypress, and mulberry trees. (Las moras is Spanish for mulberries.)

Fort Clark Springs’ Old Guardhouse Museum, set in a stout 1870s structure, chronicles the fort’s history. Vintage weapons, uniforms, and gear, along with photos, maps, and dioramas, recall the fort’s cavalry era; such notable officers as General Jonathan M. Wainwright; and famous local units, including the Black Seminole Scouts, a key military detachment during the Indian Wars.

Particularly fascinating displays include a pastoral mural of a shepherd and his flock painted in 1944 by a Nazi prisoner of war held at Fort Clark; and in front of the building, a large metal megaphone—about four feet long and three feet in diameter on its wide end—which the bugler used to broadcast his musical signals.

The Whitehead Memorial Museum, Del Rio

Natural springs are also a cornerstone of Del Rio, a city of about 36,000 located on the Mexican border, 30 miles west of Fort Clark Springs. The San Felipe Springs have long been a refreshment point for travelers, with historical mentions dating to the Spanish explorers. A popular swimming hole is located at Horseshoe Park, just off US 90.

An 1870s canal system distributes spring water to farms around the area and gives Del Rio’s historic neighborhoods the feel of a tree-lined oasis. One of the irrigation canals runs across the grounds of the Whitehead Memorial Museum, a two-acre property circled by small buildings containing exhibits about various aspects of local history.

Visitors enter the Whitehead museum through the original wooden doors of the 1871 Perry Store, a limestone mercantile building. The exhibits run the gamut, from ranching and pioneer life to the railroad, Laughlin Air Force Base, religion, and medicine. The winemaking exhibit displays 19th-Century presses used by Italian immigrants who grew grapes in the area. (Val Verde Winery, established in 1833, is a half-mile from the museum and offers tastings and tours.)

The museum also tells the story of Judge Roy Bean, the opportunistic 19th-Century saloon owner and lawman of nearby Langtry (more on Bean later). Bean is buried on the museum grounds, and a series of dioramas and artifacts relates his Wild West tale, including the 1910 traveling piano of the English actress Lillie Langtry, for whom Bean professed a proud infatuation.

Lake Amistad

Traveling north out of Del Rio on US 90, drivers come quickly upon Amistad National Recreation Area. The Amistad Visitor Information Center, located six miles from town, provides advice on exploring the scrubby hills surrounding Lake Amistad, along with the picnic sites, campgrounds, hiking and biking trails, swimming coves, and boat ramps that access the water. Angling for bass and catfish is the most popular activity on the lake, rangers say.

The Visitor Center houses exhibits on the native people who inhabited the area and their various styles of rock art. A large reproduction of the Panther Cave pictograph site in Seminole Canyon offers a close-up view for those unable to make the boat trip that’s required to see the remote site in person.

A few miles west on US 90, the road makes its first pass across Lake Amistad. Depending on the weather, the water shimmers with every shade of blue imaginable, from bright cobalt under a brilliant afternoon sky to a marbled blue-gray under morning clouds. Amistad Dam, a joint project of the United States and Mexico, collects the water of three rivers: the Rio Grande, the Pecos, and the Devils. The two nations built the dam in the 1960s, spurred to action by Hurricane Alice of 1954, which caused catastrophic flooding on both sides of the border.

Located a couple of miles west of the Visitor Center, the Diablo East area has a boat ramp, restrooms, and a 1.5-mile loop trail with a cliff view overlooking the water. If you’ve got a boat, Amistad’s Pecos River boat ramp—another 30 miles to the west—provides a serene opportunity to paddle under the towering US 90 bridge and limestone canyon walls, and to explore tranquil hidden coves. Watch for kingfishers, coots, osprey, and herons, and listen for the odd shouts of free-range goats bleating across the canyon.

Seminole Canyon State Park White Shaman Preserve

West of Del Rio and the main body of Lake Amistad, US 90 enters vast desert-like terrain, punctuated by spindly sotol and lechuguilla stalks, and softened by the grays and greens of cenizo and huisache. The road undulates with the landscape, passing through stratified road-cuts that reveal 100 million years of geologic history. When the highway crests above the surrounding desert, its vistas extend across boundless rolling hills and to distant Mexican mountain ranges.

The drive creates a sense of timelessness and isolation that’s fitting for a visit to Seminole Canyon State Park and the Rock Art Foundation’s White Shaman Preserve, where colorful 4,000-year-old paintings on canyon walls illustrate the art, symbolism, and lifeways of the Lower Pecos people. About 300 Lower Pecos pictograph sites have been recorded within a 60-mile radius of the juncture of the Pecos River and the Rio Grande.

At the White Shaman Preserve, located about 10 miles west of Comstock, the nonprofit Rock Art Foundation offers tours to the oldest of these sites every Saturday at 12:30 p.m. (September through May). The 1.5-mile, round-trip hike descends into a side canyon overlooking the Pecos River and the dramatic US 90 bridge over the Pecos. Along the way, guides like Jack McDonald, a foundation board member, describe the hunter-gatherer lifestyle of the Lower Pecos people and how they survived in such a tough environment. For example, the ubiquitous sotol plants provided food—its roots were baked in earthen ovens—and fiber for weaving material.

The White Shaman Pictograph Site is set in a sheltered grotto. Tour participants get a breathtaking view of the mysterious figures, including the namesake White Shaman, a human-like figure with deer horns and an atlatl spear, a serpent figure, and a person on a boat.

“What we’re looking at right here is the oldest book in North America,” McDonald says. “For the people who drew this 4,500 years ago, it is their belief of the genesis of mankind. All over this you see death and rebirth. It’s no different that any other belief system. It’s just not written in words. It’s written in pictographs.”

At Seminole Canyon State Park, located 1.5 miles east of the White Shaman Preserve, park rangers and volunteers lead tours to the Fate Bell Shelter (Wednesdays-Sundays). Tours depart from the park headquarters, and it’s worth arriving early to check out the museum, which chronicles regional history from the arrival of humans about 12,000 years ago to the construction of the Southern Pacific Railroad in the 1880s and the sheep- and goat-ranching industry of the 20th Century.

The two-mile, round-trip hike to Fate Bell Shelter navigates a steep limestone staircase to the floor of Seminole Canyon, where pictographs in red, yellow, white, and brown depict human-like figures, a feline with a tail that arches over its back, and what appears to be a sotol plant. Yucca and sotol were paint ingredients, Park Ranger Tanya Petruney notes, as the Lower Pecos people mixed the plants’ saponin extract with colored ochre from crushed rocks and deer bone marrow.

Departing the canyon, a Texas earless lizard skitters across the path. Archeologists say the Lower Pecos people would have eaten such lizards. So would the red-tailed hawk circling above the canyon, its underwings radiating a bright-white translucence against the desert sun.

Langtry

Perched on a dusty ridge overlooking the Rio Grande, the tiny town of Langtry lies in the thick of the Lower Pecos Canyonlands, about 18 miles west of the Pecos River. Langtry sprang up in 1882 as a railroad camp during the construction of the Southern Pacific line. Among the profiteers following the railroad was Roy Bean, a tent-saloon operator who would come to symbolize Langtry’s Wild West roots.

In an effort to quell the lawlessness in area railroad camps, the Pecos County Commissioners Court appointed Bean as the Justice of the Peace in August 1882. The grizzled Bean relished the position, branding himself “The Law West of the Pecos” and holding court in his saloon alongside the railroad tracks.

The Judge Roy Bean Visitor Center (a TxDOT Travel Information Center) preserves Bean’s 120-year-old wooden saloon and his adobe home. Visitors can walk inside both structures to see the wooden bar and period furnishings. Other Bean artifacts are displayed inside the Visitor Center, including his weathered copy of the 1897 Texas Revised Statutes book and his 2.5-foot ornately carved walking stick.

Inside the saloon’s billiard hall, newspaper clippings and historical photos chronicle what was perhaps Bean’s most famous exploit—hosting the Fitzsimmons-Maher heavyweight world-title boxing match on the Mexican bank of the Rio Grande in 1896. Violating both Texas and Mexican bans on the fight, Bean built the ring and a footbridge across the river for the boxers, spectators, and reporters who had come to Langtry by train. Visitor Center staffers can point you to a nearby historical marker overlooking the river-bottom site of the bout, tucked against jagged yellow limestone cliffs.

“These eastern sportswriters had never seen a character like Roy Bean,” says Jack Skiles, a Langtry native who wrote the book Judge Roy Bean Country. “When I was growing up, all the old-timers referred to him as ‘that old reprobate.’ But he was good in lots of ways too. He saw to it that local widows had wood to keep them warm during the winter and to cook with, and that the local school got help when it needed it.”

Sanderson

Roadside development thins beyond Langtry as US 90 pierces the Chihuahuan Desert. About 60 miles west of Langtry, the little town of Sanderson also owes its existence to the Southern Pacific Railroad.

As the halfway point between San Antonio and El Paso, the railroad located a division office here in 1882. Roy Bean opened a saloon here, too, but he left soon after local competitor Charlie Wilson spiked Bean’s whiskey barrels with kerosene, says Bill Smith, a walking encyclopedia of Sanderson history who runs the Terrell County Memorial Museum and the Terrell County Visitor Center.

Most of Sanderson’s historic railroad structures are gone, but the town retains its 1930 Mediterranean-style Terrell County Courthouse and several stops rich in local history. The 2.2-mile Cactus Capital Hiking Trail (named for Terrell County’s abundance of cactus) climbs a flattop mesa and provides a bird’s-eye view of the town, including Sanderson Canyon, the normally dry arroyo that flash-flooded on June 11, 1965, wiping out much of the town and killing 26 residents.

Memories of the flood are still fresh at the Visitor Center, which carries books and pamphlets about the tragedy and which this summer opened a Heritage Garden, its esperanza and pride-of-Barbados flowers memorializing the flood victims. The Memorial Museum, which is set in a 1907 home, displays the June 18, 1965, edition of the Sanderson Times, the first edition published after the flood, among its collection of artifacts covering a wide swath of local history.

Down US 90 from the Visitor Center, the Outback Oasis Motel offers clean and comfortable lodging, as well as a lesson in herpetology at The Snake House, a display of 35 different snakes in a room adjacent to the front lobby. The collection includes a gray-banded kingsnake—an elusive, non-venomous snake striped orange, gray, black, and white and found only in this region—and several kinds of rattlesnakes.

Kept in secure glass tanks, the rattlers are prone to vibrating their tails when visitors step close. With multiple people in the room, the symphony of rattles seems to emanate from every direction.

Some might find this unnerving. But it’s worth hearing if for no other reason than to be alert while walking the rugged countryside of Southwest Texas and the Big Bend. Owner Roy Engeldorf notes that it’s easy to avert danger if you encounter a rattlesnake in the wild—simply take a step back and walk away.

There’s plenty of ground still to cover, anyway. The journey abides.