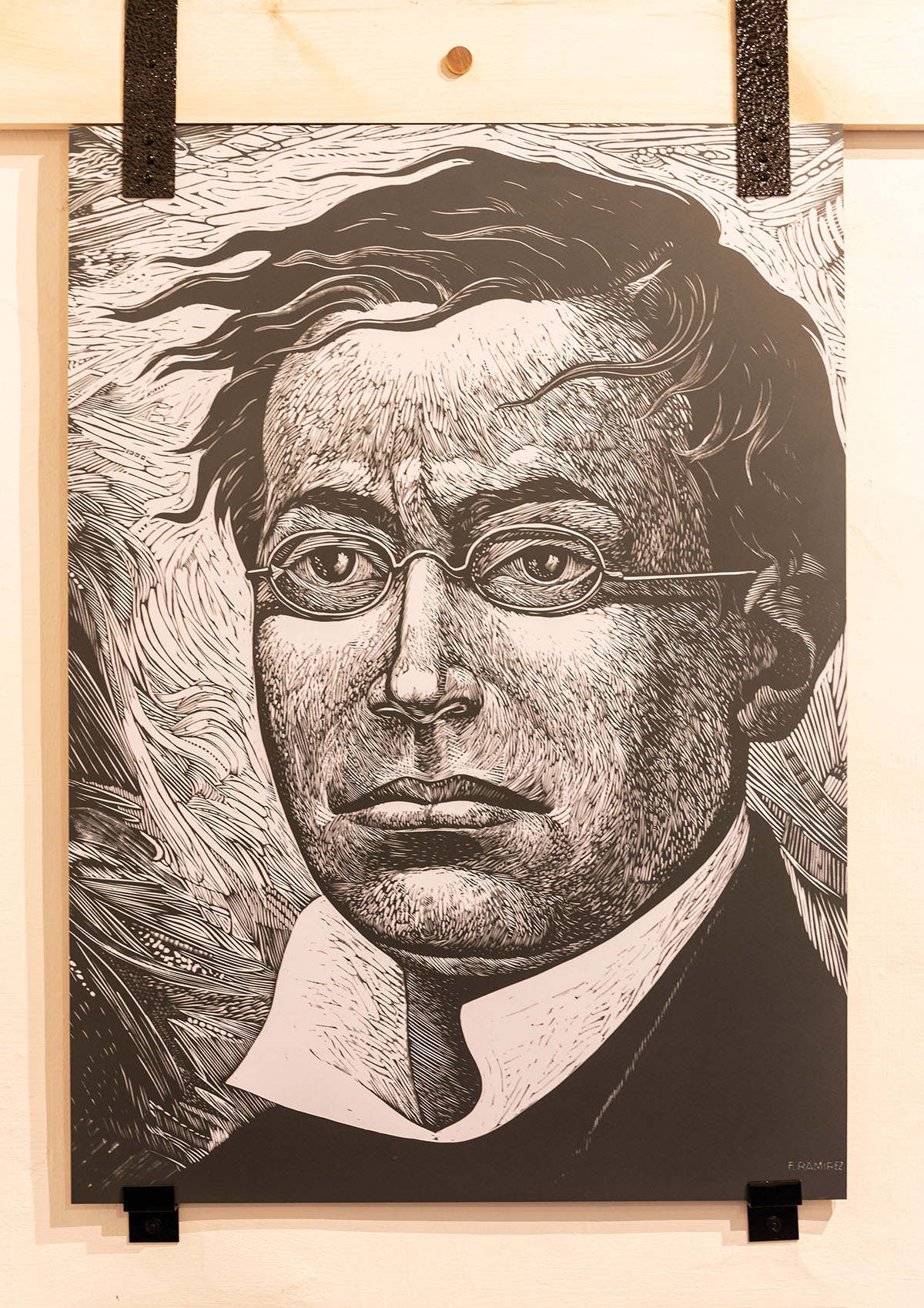

The Zaragoza Birthplace State Historic Site recounts his life and times with artifacts and portraits.

The Zaragoza Birthplace State Historic Site, located adjacent to Presidio La Bahía, recounts his life and times. Though he lived in Texas for only the first five years of his childhood, Zaragoza’s story reflects the turbulence of the Texas frontier—a revolutionary

era marked by shifting borders and changing governments under pressures of both colonialism and local demands for independence.

“There is no way to separate the histories and experiences of Texas and Mexico, then or now,” says Thomas Kreneck, a professor emeritus of Texas A&M University-Corpus Christi. “When Zaragoza was truly active as a national figure in Mexico, both areas shared people and similar events. Texas—and thus the United States—and Mexico were going through struggles of nation-

building. In Mexico, this would lead to the French intervention, while in the United States the 1850s saw the coming of the Civil War.”

Zaragoza’s parents met when his father, Miguel Zaragoza, originally from the Mexican port city of Veracruz, was stationed with the Mexican infantry regiment at San Antonio de Béxar in 1825. His mother, María Teresa de Jesús Seguín, was a relative of Juan Seguín, a Tejano politician from San Antonio who fought with Sam Houston in the Battle of San Jacinto. By 1829, the Mexican army sent Miguel Zaragoza to Presidio La Bahía. The Spanish had established the fort to discourage French settlement in Texas, and then the Mexican authorities used it to deter rebellious Texas settlers. The Zaragozas lived near the fort in the small village of La Bahía. There, in 1829, the same year the village adopted the name Goliad, Ignacio Zaragoza was born.

Built in a South Texas vernacular style, the three-room historic site tells Zaragoza’s story and displays commonplace items of his day, such as a water barrel, candles, utensils, and flat-brimmed hats. After conducting an archeological excavation, the Texas Parks and Wildlife Department reconstructed the crumbling house in the 1970s. According to the narrative chronicled in the home, the Zaragozas moved to Mexico in 1835, first to San Luis Potosí and then Matamoros.

Military Life

Ignacio Zaragoza dabbled in the seminary and then the mercantile business in Monterrey, but by the early 1850s, he had joined the National Guard of Nuevo León. Promoted to the rank of captain, Zaragoza sided with Benito Juárez’s effort to establish a democratic and constitutional government. At that point, Mexico had been in turmoil—beset by civil war, political instability, and territorial disputes—since winning its independence from Spain in 1821.

Zaragoza participated in important battles in Saltillo and Monterrey against forces led by Antonio López de Santa Anna. According to the Handbook of Texas, he was so occupied by Mexico’s War of the Reform (1857-60) that he was unable to attend his own wedding to Rafaela Padilla in Monterrey. His brother, Miguel Zaragoza, stood in as his proxy. The family was plagued by tragedy: Three of the couple’s children died in infancy, and Rafaela succumbed to illness in 1862.

By that time, Mexico had suspended payments on debts to England, Spain, and France, prompting the three European powers to seize the port of Veracruz to collect outstanding funds. But it soon became apparent that France had even more aggressive intentions as French troops began a march inland, headed for the capital of Mexico City.

They had to pass through Puebla first, however. Expecting a surrender, the French made the decision to attack the city by attempting to ascend two fortified hilltops, where they were routed.

“The national arms have been covered with glory,” Zaragoza wrote in a battle report. “I can state with pride that not once, during the long struggle which it sustained, did the Mexican army turn its back on the enemy.”

Mexico celebrated Zaragoza as a national hero, but his time in the limelight was short-lived. On Sept. 8, 1862—only four months after the Battle of Puebla—he died of typhoid fever at the age of 33.

Historic Goliad

The Spanish established Goliad in 1749 with the founding of a frontier mission and Presidio La Bahía as a military post. The town remains a treasure of heritage travel.

Nuestra Señora de Loreto de la Bahía Presidio. Originally built in 1749 and reconstructed in the 1960s, the site suggests how the Alamo might look if San Antonio had not grown up around it.

presidiolabahia.org

Goliad State Park and Historic Site. The 276-acre park features the reconstructed Nuestra Señora del Espíritu Santo de Zúñiga

Mission, the reconstructed Zaragoza Birthplace State Historic Site, and the El Camino Real de los Tejas Visitors Center. tpwd.texas.gov/state-parks/goliad

Market House Museum. Housed in an 1871 building, the museum brings the history of Texas’ third-oldest town to life.

Cinco de Mayo

The first American celebrations of Zaragoza’s victory on Cinco de Mayo took place in California only weeks after the battle, according to the book Cinco de Mayo: An American Tradition, by UCLA professor David E. Hayes-Bautista. Also in the 1860s, the Texas border town of San Ygnacio celebrated Cinco de Mayo in 1867, the Tejano scholar Américo Paredes wrote in A Texas-Mexican Cancionero. In Goliad, historians William and Estella Zermeno keep in their collection a copy of a Spanish-language document dated Jan. 24, 1886, announcing what is believed to be the first General Zaragoza Society in Texas, formed at Los Olmos. The Zermenos are involved with the Goliad-based society, one of several such groups in South Texas that promote Mexican culture, traditions, and student scholarship.

Cinco de Mayo commemorates the Battle of Puebla, which took place on May 5, 1862.

In Texas, Cinco de Mayo celebrations were usually confined to Mexican American neighborhoods, but they often brought races together. In 1893, The Galveston Daily News reported on the celebrations in Del Rio, where the Anglo and Hispanic populations lived on opposite sides of San Felipe Creek. “Many Americans from this side of the creek were over in the Mexican town,” according to the report. A procession included bearers of both the American and Mexican flags: “They were crossed, showing that the two governments were at peace.”

At Eagle Pass, a short distance down the Rio Grande, the newly organized musical ensemble Banda Mexicana General Ignacio Zaragoza made its first public appearance at the town’s inaugural Cinco de Mayo festival in 1909, reported the Eagle Pass News-Guide. Later that year, the band played at Fourth of July and Diez y Seis de Septiembre (September 16th) celebrations. The latter, often confused with Cinco de Mayo, marks the official Mexican Independence Day.

Goliad started recognizing Cinco de Mayo at some point in the late 19th century, according to displays in the Zaragoza Birthplace State Historic Site. In 1944, locals formed a General Zaragoza Society, which in the 1960s held the first annual Fiesta Zaragoza. Typically held around May 5, Fiesta Zaragoza features live Tejano music, street food, barbecue cookoffs, arts and crafts vendors, and a ceremony honoring General Zaragoza at the Zaragoza Amphitheater.

Estella Zermeno says her father, who was born in Goliad in 1897, played in the ruins of the original Zaragoza home as a child. In 1836, during the Texas Revolution, Col. James Fannin had ordered the house and other stone structures of Goliad destroyed as part of the Runaway Scrape, when Texians fled from Santa Anna’s advancing army after the Battle of the Alamo. During her tenure as a historic-site docent, Estella says, she learned that other Tejanos who had lived in La Bahía and Goliad fought with Zaragoza’s forces at Puebla.

“We need to remember what our people have done,” Estella says. “There isn’t much in the history books about Tejanos, but we were here a long, long time ago.”

Throughout the Lone Star State, Ignacio Zaragoza remains a symbol of native Tejano valor and independence. In the 1950s, Paredes wrote, he learned of a Zaragoza tribute song from a Zapata County balladeer. He traced the song to a San Ygnacio guitarrero named Onofre Cárdenas, who performed the song at the town’s 1867 Cinco de Mayo celebration. It went on to become part of the border’s oral tradition. Translated from Spanish, Cárdenas proclaimed, “God save thee, brave Zaragoza, unconquerable general of the border; I and all free men salute your flag that waved unceasingly in Puebla.”