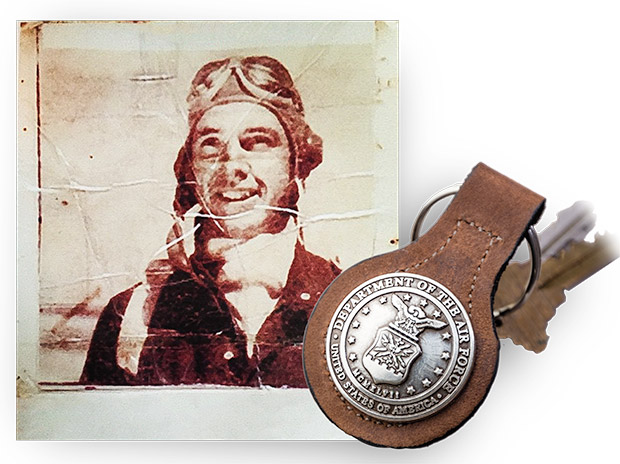

(Photo courtesy Clayton Maxwell of Air Force cadet Stanley Price; (keychain) Brandon Jackobeit.)

I know a museum has triumphed when I leave a bit stunned, new realizations having just taken hold. Before my recent visit to the National Museum of the Pacific War and Admiral Nimitz Museum in Fredericksburg, I had considered the site a destination solely for World War II history buffs. And while I was surprised to find the artifacts of war so intriguing, that realization is not the one that left me teary-eyed in the penultimate exhibition room. I was startled by how, in weaving together the complex threads of history, the museum tells the story of a whole generation— and in that telling, there is a story of my family, too.

The National Museum of the Pacific War is at 340 E. Main St. in Fredericksburg. Call 830/997-8600.

The awareness hits me right away, in the first exhibition room, when I read one of FDR’s famous quotes, emblazoned large upon the wall, “To some generations much is given. Of other generations much is asked. This generation of Americans has a rendezvous with destiny.” It dawns on me that FDR was talking about my mother’s mom and dad, Joy and Stanley Price, aka Nana and Papa, who played outlandish games with my sister and me in the attic and took us to the dollar store for shopping sprees. But now, standing at the beginning of this labyrinth of exhibition halls, taking in FDR’s dignified pronouncement, I get a whole new perspective on something I had never fully comprehended: that my grandparents had been two young people swept up in a wave of history that changed the world. And it changed them, too.

My grandmother, at the age of 19, married a fighter pilot named Edward Raymond Woolery; they were stationed in the Philippines when she gave birth to my uncle. A few months before the Pearl Harbor attack, she and her son were sent home to San Antonio. She didn’t find out that her husband had died in combat until months later, when an Air Force officer knocked on the door with the news. A wartime widow with a small child, she then met and fell in love with my grandfather, also an Air Force pilot, who was stationed in San Antonio at that time as a flight instructor. They married and had a daughter, my mom. But he too was called away to the Pacific War, and began flying B-29s off of the island of Tinian in the Marianas. My grandmother said goodbye yet again to her husband, not knowing if he would return.

I move from room to room of the museum and take in all of the video, audio, photographs, maps, and artifacts that the museum uses to explain the war and the global forces that caused it: the U.S. isolationism that followed the Great Depression, the introduction of Japan to the West after the invasion of Commodore Perry in the mid-1800s, and the ensuing Sino-Japanese War. One thing leads to another, of course, and the museum teaches how these seemingly disparate events of history are interwoven.

I stand in the Pearl Harbor room and listen to a recording of FDR announcing war on Japan, imagining my grandparents hearing his voice over the radio 75 years ago. I watch computerized maps showing how U.S. planes steadily took over the islands that they needed in the Pacific to gain access to Japan, thinking about my grandfather making the 12-hour roundtrip flight between Tinian and Japan.

But it is in the Victory Room where I understand at a gut level how this museum presents a personal story, too. Because it is in the video of the momentous September 2, 1945, surrender ceremony aboard the USS Missouri that I get to see my grandfather flying in a tiny black plane over the Bay of Tokyo. I can’t really see him specifically, of course—but I know that he was in one of the B-29s flying in a massive air formation, floating like flocks of geese over the ship where General MacArthur, Admiral Nimitz, the Japanese foreign minister, and many Allied heads of state were signing the peace document that would end the war.

In watching that video screen, I feel a hint of what that ceremony represented to so many people—the promise of peace. And for us, it meant that my mother and my uncle were going to grow up with a father, and that my grandmother would not be widowed again.

Afterwards, into the sunshine of a perfect blue-sky day, I sit overlooking the Peace Garden. This Japanese garden, with its waves of raked white rocks representing the Pacific Ocean, was built by Japanese gardeners and carpenters in 1976 to honor the respect between U.S. Admiral Nimitz and Japan’s Admiral Togo, as well as the work Nimitz did after the war to repair relations between the two countries. A plaque reads that this garden “is a gift to the people of the United States from the people of Japan with prayers for everlasting world peace through the goodwill of our two nations.”

While I imagine this unlikely respect between two admirals from opposing sides of the war, I hold in my hands a leather key chain I’d just bought in the gift shop. Fastened to the leather is a silver replica of the Air Force Seal—an eagle clutching a shield flashing with lightening bolts. Sometimes we need an everyday object to remind us of the bigger picture, of the victories and losses that have shaped our world. This keychain is a reminder of what the museum helped me grasp in a more meaningful way—that while Joy and Stanley Price will always be two lovable grandparents, they are also, as FDR put it, part of a generation of whom much was asked, when even surviving to become a grandparent meant that you were

one of the lucky ones.