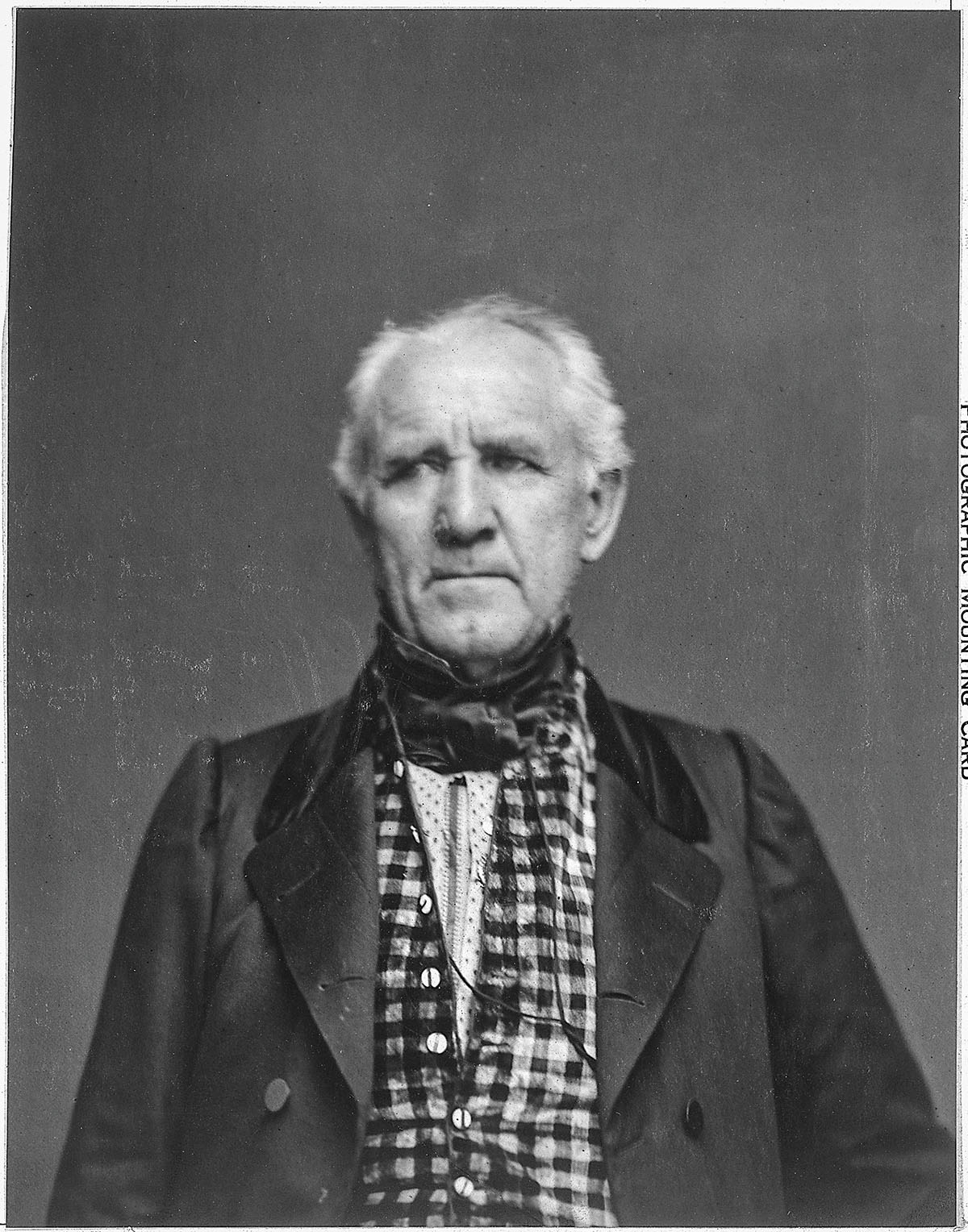

In March 1861, as the United States hurtled toward the Civil War, Texas Governor Sam Houston assembled his closest advisors late one night in the Governor’s Mansion library in Austin. He read them an extraordinary letter from President Abraham Lincoln. If Houston would hold Texas in the Union, Lincoln would make him a major general with command of 50,000 troops. Upon his advisors’ counsel, the 67-year-old governor burned Lincoln’s letter in the library fireplace. Houston said if he were 10 years younger, he would’ve accepted.

Houston was the most prominent pro-Union leader in Texas, but he wasn’t the only Texan who opposed the state’s secession. The state Legislature had been so angry at Houston’s lack of Southern fervor that it declined to reappoint him to the U.S. Senate in 1857. Two years later, however, Houston was elected governor on a pro-Union platform. The secessionists ultimately prevailed, but Texas was bitterly divided over leaving the United States. Traces of that history paint a more complete picture of the tumultuous time.

Of course, the crucial issue was slavery. In 1860, the 170,000 enslaved African Americans in Texas made up about one-third of the population. Cotton drove the state’s economy, and plantations relied on slavery for profitability. But slavery was far less essential to the rest of the economy, and in fact, nearly 75% of Texas families did not own slaves. Most Texans were cash-strapped farmers who could not afford the $800 price of a field hand (equal to about $24,700 today). Others, like the thousands of German settlers in the Hill Country, found slavery morally repugnant. Even Texas courts could be ambivalent about slavery; there were cases of slaves suing their masters for their freedom—and winning.

“The status, and especially the legal status, of slavery in Texas before the Civil War had always been tenuous and polarizing,” explains Byron King, a historian and former tour guide at the Texas State Capitol. “It wasn’t like a number of other soon-to-be Confederate states that developed fairly stable and politically secure multigenerational ‘slavocracies.’”

But secessionists held the political momentum. Texas newspapers were generally beholden to the slave-owning planter elite, and most Anglo Texans had immigrated from Southern states and were ingrained in that culture. In January 1861, a majority of Texas legislators gathered for a secession convention and submitted a referendum to registered voters. On Feb. 23, 1861, Texas voters approved it, 46,153 to 14,747.

Those numbers are deceptive. Texas Supreme Court Justice James Hall Bell, an ally of Houston’s, arrived at his polling place in Brazoria County and found it occupied by secessionist poll-watchers, one of whom handed him his ballot pre-printed “For Secession.” Bell scratched out “For,” and penned in “Against.”

“Judge Bell,” said the presiding official, “I am very sorry to see you cast that vote, and you are going to regret it.” Indeed, Bell was soon voted off the Court. Such intimidation artificially inflated the majority vote, and many Unionists did not risk voting at all.

Bushwhacked

Secessionist vigilantes also turned to arson and murder to make their case. Across Texas, several wells and caverns took on the nickname “Dead Man’s Hole,” where the bodies of “bushwhacked” Unionists were cast. Perhaps the most notorious was in Burnet County, where the corpses of 17 men, possibly more, were thrown down a 150-foot deep limestone cavity.

The questions of slavery and secession divided nobody more than the 50,000 or so recent German immigrants.

“The Germans who came here were not just looking to do better economically; they had political ideals,” says Warren Friedrich, a former board member of the German-Texan Heritage Society. “They were proud to be Americans, maybe even prouder to be Texans, and they took exception to Texas wanting to leave the Union.”

Many in Central Texas felt it better to “go along to get along,” and a couple of volunteer German companies formed in New Braunfels and joined the rebel army. West Texas was different: Union sentiment was strong, especially among the intellectuals, or freidenker, south of Fredericksburg. They had come to Texas to escape political repression, and they felt keen sympathy for those in bondage.

In 1862, between 60 and 70 of these “freethinkers” headed for Mexico, which was the usual escape route for Texas loyalists intending to make their way to the Union army. In the Battle of the Nueces, Confederate irregulars ambushed them near Fort Clark, killing 28. Another eight were killed in a second attack. After the war, the victims’ families gathered their bones and took them to Comfort, where they were buried with honors beneath the Treue der Union (True to the Union) Monument. To this day, an 1866 flag with 36 stars flies at half-staff.

Even this was not the high-water mark of vigilante violence in Texas. That distinction belongs to the so-called Great Hanging in Gainesville. In Cooke County, along the Red River boundary of Texas’ northern border, locals had voted down the secession ordinance. After the Civil War broke out, Confederate irregulars rounded up suspected Unionists and draft dodgers. Tried for treason and insurrection, the defendants were condemned on simple majority vote, and some 19 acquittals were reversed by mob demand. In all, 41 men were hanged in October 1862. In 2014, descendants of the victims placed a monument in a small park near the site of the executions, six blocks east of the county courthouse.

Lone Voices

Houston’s iconic stature afforded him some protection, but others weren’t as lucky. A mob chased Andrew Jackson Hamilton, Austin’s congressman, out of town for opposing the Confederacy. He sought refuge on his brother’s ranch 25 miles to the west, where he hid out in a limestone sinkhole. Hamilton escaped the state, served as a Northern general, and returned as governor during Reconstruction. His hiding place is now known as Hamilton Pool, the scenic centerpiece of a 232-acre nature preserve.

First Lady Margaret Houston spent the night of March 15, 1861, in the Governor’s Mansion library, listening to Houston pace upstairs as he wrestled with whether to swear allegiance to the Confederacy as the secession convention required him to do the following day. When he came down in the morning, he said, “Margaret, I will never do it.”

Houston relinquished his office and moved with his family to Independence. But he was given no peace in retirement, called upon to give speeches defending his position. He delivered the greatest one in April 1861 in Galveston from the balcony of the Tremont Hotel, which still welcomes visitors today.

“Some of you laugh to scorn the idea of bloodshed as the result of secession, but let me tell you what is coming,” Houston said. “Your fathers and husbands, your sons and brothers, will be herded at the point of the bayonet. While I believe with you in the doctrine of state rights … the North is determined to preserve this Union.”

The Civil War, of course, proved him right.

Relics of Texas’ Anti-Secession Resistance

The Governor’s Mansion in Austin is where Sam Houston burned Lincoln’s letter in the library fireplace and made the decision to give up the governorship rather than pledge allegiance to the Confederacy. The Union sword of Edmund Davis, a Brownsville judge who served as Texas governor during Reconstruction, is on display in the mansion’s collection. tspb.texas.gov

Hamilton Pool Preserve, west of Austin, is where Congressman Andrew Jackson Hamilton, a Union sympathizer, hid before escaping the state. parks.traviscountytx.gov/parks/hamilton-pool-preserve

Dead Man’s Hole in Burnet County is where vigilantes dumped the bodies of anti-secessionists, off Shovel Mountain Road (County Road 401), on a dirt road about 600 feet north of the intersection with Burnham Ranch Road (County Road 405).

The Treue der Union Monument in Comfort is where the bones of German-Texan Union loyalists are buried. comfortchamber.com

Jordan-Bachman Pioneer Farms in Austin harbors the historic home of Texas Supreme Court Justice James Hall Bell, an opponent of secession. pioneerfarms.org

The Great Hanging Monument in Gainesville memorializes 41 men who were executed in 1862 for not joining the Confederacy. It is located between Main and California streets, six blocks east of the county courthouse.