Tales of Texas Grit

by Jac Darsnek

Texans are no strangers to adversity. When disaster strikes, we respond with characteristic tenacity and neighborly spirit.

All of Texas history seems to conspire to teach one lesson: Bounty and risk walk hand-in-hand across this land. Geography and climate combine to afflict the Lone Star State with nearly every variety of calamity known to humankind: hurricanes, tornadoes, droughts, floods, vermin infestations, wildfires, diseases, dust storms, rampaging insects, torrid heat waves in the summer, moaning cold snaps in the winter, allergens that lay grown men low, boll weevils, skunks, and regions of harsh landscapes filled with sharp plants that can put an excruciating hurt on you. “Being a Texan is a full-time job,” my high school football coach used to say. He was right. Historically, living here has required 100% commitment.

I have been privileged to bear witness to the challenges and hard-won successes of the past as the founder of Traces of Texas. The online community devoted to sharing and preserving historic images of the state has grown from its infancy in 2010 to include 800,000 followers on Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram.

It’s terribly sad to be alive and aware and to look around at all that’s being lost to COVID-19. The human toll has been devastating. To add to the heartbreak, venerable establishments are struggling, failing, and disappearing. Nobody knows what will have changed when dawn comes to the new paradigm. But history teaches us that Texans endure. We soldier on. An old farmer in Dimmitt once described his ancestors as “tougher than a sack full of hickory knots.” That stuck with me.

Long-gone Texans are looking out at us across the decades, reassuring us that it’s going to be all right and that, come what may, Texas will abide. We’ll get through these challenges as we always have, with open-hearted kindness for our neighbors and by remembering the fortitude of those who came before.

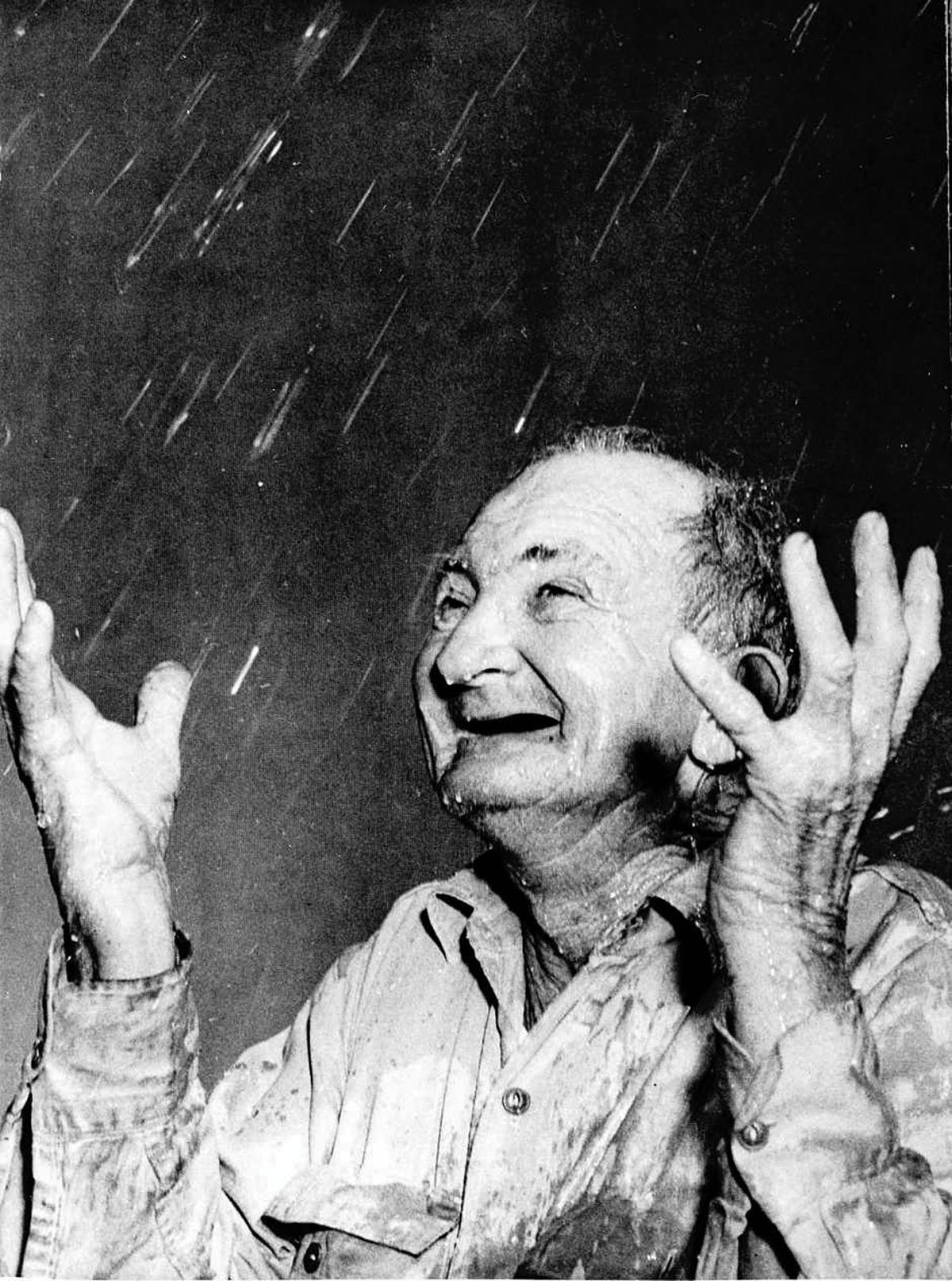

The 1950s Texas Drought, 1951 (Opening photo, above)

Known as the most catastrophic drought in state history because of its length and widespread effect, the drought of the 1950s included the second-, third-, and eighth-driest single years up until that point. Sixty years later, 2011 would become the driest year in state history, surpassing the record set in 1917. Here, Sam J. Smith, a farmer in San Antonio’s Belgian Gardens district, rejoices in the rain on Easter Sunday, March 25, 1951. San Antonio Light photographer Harvey Belgin received a Pulitzer Prize nomination for the photo.

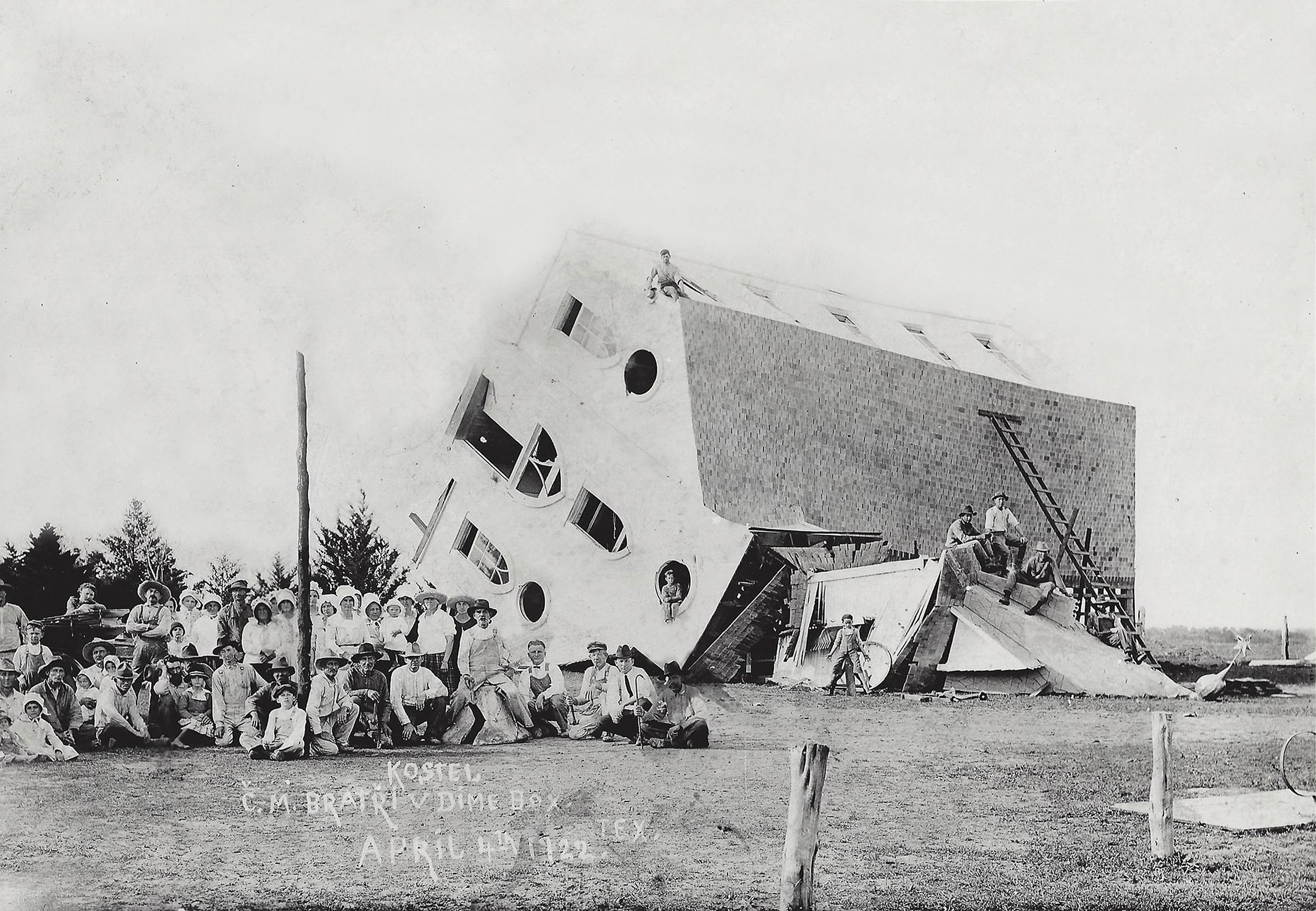

Dime box Tornado, 1922

A tornado struck the Czech community of Hranice (near Dime Box, between Austin and College Station) on April 4, 1922. The natural disaster knocked over the Czech Moravian Brethren Church. Here we see three photos of the church: shortly after it was completed in 1911, after the tornado struck, and upon the congregation’s rebuilding of the church in August 1924. Tragedy struck the church again in July 1954, when a fire ripped through it. And yet the church was rebuilt a third time and is currently holding services at the same location on 8361 Farm-to-Market Road 141.

Trinity River Flood, 1916

It’s important in life to keep one’s wits and priorities in order, especially when disaster strikes. That seems to be the advice of these Texans in Fort Worth when they decided to pause for coffee after the Trinity River flooded in 1916. The viewer can almost imagine the conversation: “Earl and I are going to pull down that wall over there, but first we’re going to need a cup of joe.” This flood tested the Lake Worth dam and levee systems, which were under construction at the time. Everything held up and no fatalities were reported.

San Antonio River Flood, 1921

Young girls find relief at a Red Cross station in San Antonio after the 1921 flood of the San Antonio River, which left at least 51 dead and 14 missing. The San Antonio Light wrote that water ranged from 10 to 30 feet high and “carried houses from their foundations, swept motor cars away, destroyed concrete bridges, tore down trees and poles and ripped up paving in the streets like … pebbles.” The community banded together, and 600 volunteer workers showed up to help. The tragedy caused the city to seriously consider flood control and resulted in the building of Olmos Dam and, ultimately, the River Walk.

The Dust Bowl, 1930s

The Dust Bowl, a series of dust storms caused by severe drought and shortsighted farming methods like overgrazing and deep tilling, wreaked havoc on the Panhandle Plains in the 1930s. A farmer, perhaps taking a break from the rigors of rural life, smokes a pipe in downtown Stanton in 1937 (above). An automobile flees a dust storm near Amarillo in 1936. In 1937, a family on the road near Memphis travels with all their earthly belongings. They told photographer Dorothea Lange they were bound for the Rio Grande Valley, where they hoped to pick cotton. Lange also photographed an abandoned farm (below) in the Coldwater District north of Dalhart in 1938.

Galveston Hurricane, 1900

The hurricane that struck Galveston on Sept. 8, 1900, obliterated the town, destroying or severely damaging nearly every structure. Amid the destruction, a young boy smiles as recovery efforts begin. To mitigate future floods, Galveston built a seawall 17 feet high and 10 miles long (bottom of page, between 1910 and 1920). Nobody would have blamed the citizens of Galveston if they walked away after the disaster in search of less calamitous surroundings. Instead, the residents went to work rebuilding the city, and new businesses began popping up. In testament to the town’s efforts to reinvent itself, immigrants Sebastian and Giorgia Mencacci and their family opened their grocery store at 21st Street and Avenue O ½ in 1910. The couple arrived in the U.S. from Italy in 1901 and moved from Chicago to Galveston to open the store. They stayed in the city for the rest of their lives.