Historians believe the Comanches sometimes crossed the Rio Grande into Mexico at San Vicente Crossing in Big Bend National Park.

The final months of summer were both the best and worst parts of the year in the Big Bend country during the mid-1800s. In August, monsoons brought rainfall and relief from the Chihuahuan Desert’s blistering heat. Dry creeks began to flow, springs were replenished, and runoff filled depressions in rock formations, creating natural cisterns. Grass for grazing reappeared across arid basins. When September rolled around, the Big Bend was at its most hospitable—which is why the Comanches showed up when they did.

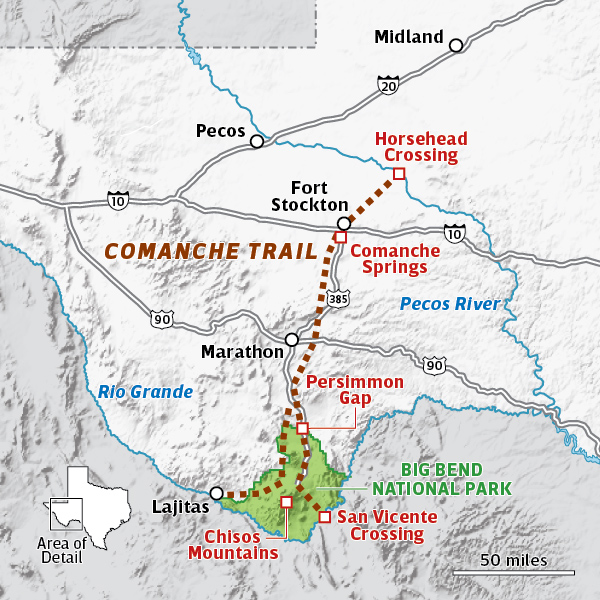

Hundreds, possibly thousands, of Comanches made the trek each year from their home territories across the Southern Plains. They came to make raids into Mexico to capture horses, and sometimes mules and humans. The “Lords of the Plains” valued horses the most; they needed them for hunting, warfare, and trade. Reaching the Trans-Pecos region of Texas, tribal bands navigated a route now referred to as “the Comanche Trail” through desert scrublands and mountains. Once in Mexico, they raided ranches and villages in the northern states of Chihuahua, Coahuila, Durango, and elsewhere. After a few months, the parties herded their newly pilfered animals back north.

Other Indigenous people, including the Apache, blazed the trail, according to Spanish records from the 1700s. But the Comanches made the most extensive use of it, especially from the 1830s to the late 1850s, when a growing population of settlers from the U.S.—many hostile to Native Americans—made routes through eastern parts of Texas too dangerous for the Comanches. The Big Bend was mostly unpopulated and offered a more direct path to haciendas in northern Mexico, an area with minimal military presence.

Map by Alan Kikuchi

History books and websites such as the Handbook of Texas contain various accounts of the routes of the Comanche Trail. It’s a perplexing topic. Rather than a cohesive nation, the Comanche world was made up of autonomous divisions, each consisting of multiple bands, who lived in widespread regions. Some of them, such as the Yamparika band, lived most of the year hundreds of miles away in eastern Colorado and western Kansas. Encountering divergent records, I eventually came to wonder if a single Comanche Trail even existed. I decided to travel to the Big Bend area to try to nail down the route. If it was real, I wanted to attempt to trace it using modern highways.

Joaquín Rivaya-Martínez, an associate professor of history at Texas State University who studies Indigenous people of the Southwest, says the trail to Mexico was one of multiple Comanche traveling routes. “In Texas, people talk about the Comanche Trail or the Great Comanche War Trail, but in reality, there were plenty of trails,” he says. “There are ‘Comanche Trails’ recorded on maps from the 1830s, including one by Stephen F. Austin himself, that go from North Texas to what is now the border between Louisiana and Texas.”

While many of those paths are lost to time, Rivaya-Martínez says the Comanches’ route across Big Bend is fairly well established, thanks in part to the natural landscape: The rockiness and aridity of the Trans-Pecos region helped to preserve the trail. For four decades, retired Big Bend National Park archeologist Thomas Alex has studied the contours of the Comanche Trail, at times tracing it in a small aircraft. “You can find it on Google Earth, if you know where to look,” he says.

The Comanche Trail received heavy use. Alex says he has discovered places where thousands of hoofs over time wore ruts in the trail bed. When he explored stretches of the route in the national park, he found pottery shards and other relics dating from the 1800s. (The park doesn’t identify artifact sites to protect them from looters.) “The Mexican-bound raids were often large-scale efforts that drew members from several Comanche divisions,” Oxford scholar Pekka Hämäläinen wrote in his 2008 book, The Comanche Empire. As many as 400 warriors wearing breechcloths, leggings, and moccasins could make up a raiding party.

“Think of the Comanche Trail as a rope that is frayed on both ends,” Alex says. The solid part of the rope runs about 150 miles south from Horsehead Crossing on the Pecos River to Big Bend National Park. On the northern end, various strands of reported Comanche trails from places like Muleshoe, Odessa, Big Spring, the Monahans Sandhills, and Fort Sumner, New Mexico, converge at Horsehead Crossing, which today is located on a private ranch about 30 miles northeast of Fort Stockton. A state historical marker at the intersection of Farm-to-Market Road 11 and Horsehead Road, roughly midway between Girvin and Imperial, recalls the crossing’s significance.

The Comanches navigated Chihuahuan Desert grasslands and mountains like these near Marathon.

On a scorching morning this past summer, I set off in a car from Horsehead Crossing to trace the Comanche Trail based on what I’d learned. At first glance, the Pecos doesn’t look to be a particularly treacherous river, but quicksand, unpredictable currents, and steep embankments make it nearly impossible to ford except at Horsehead Crossing. The water is strongly alkaline, and thirsty horses and cattle that drink too much of it can die. According to legend, Native people placed animal skulls in mesquites to mark the crossing, which is how it got its name.

After leaving this mesquite-littered country, the trail moves southwest until it reaches Comanche Springs, located near current-day Fort Stockton’s courthouse square. Agricultural pumping dried up the six artesian springs by 1960, although in recent years water has again flowed during winter months when farming fields are fallow. In the mid-1880s, the springs were a reliable water source. Legend holds that Native tribes agreed not to engage in warfare with each other when they were at the springs. That’s how important the location was.

From there, the trail runs south to the vicinity of Marathon, paralleling US 385 through expansive grasslands punctuated by the Glass Mountains. About 20 miles south of Marathon, the solid rope of the Comanche Trail begins to fray. A branch known as the San Carlos Trail breaks away and rolls toward the west. But I stayed on 385 and drove to the Persimmon Gap entrance of Big Bend National Park, following a branch known as the Chisos Trail because it skirts the eastern slopes of the Chisos Mountains.

Driving south along Main Park Road, I followed the branch to Panther Junction Visitor Center, where evidence of the trail dissipates. Alex says the Comanches would use whatever river crossing made the most sense given the conditions. One they favored was near the ghost town of San Vicente, 20 miles southeast of Panther Junction.

The western branch of the Comanche Trail, known as San Carlos Trail, veers down the western slope of the Chisos and reaches the river at Lajitas, a historical crossing. “The ford on the river is still there today, but where the Comanches crossed was destroyed by the Lajitas golf course construction,” Alex says.

The next noon, with the temperature at 115 degrees on the river, I went to Boquillas Crossing, the only operational entry point into Mexico in the Big Bend. It’s about 10 miles downstream from San Vicente. I paid $5 to be rowed across the river, then rented a horse to ride to the village of Boquillas del Carmen. As I sat astride my horse, I felt certain I was riding over a Comanche trail or two now long forgotten.

The Comanches continued to raid Mexico until the mid-1870s, although by the 1850s the raids were getting less frequent as the tribe struggled against epidemics, diminishing bison herds, and the western expansion of population growth across Texas. The last free band of Comanches, the Quahada, surrendered to the U.S. government after losing the Battle of Palo Duro Canyon in 1875. The Comanche were forced to move to a reservation in Oklahoma, and the storied Mexican raids faded into memory.