Competitor Weldon Byrd's top hand buckle, circa 1977.

O’Neal Browning was 16 years old

when he first started riding bulls.

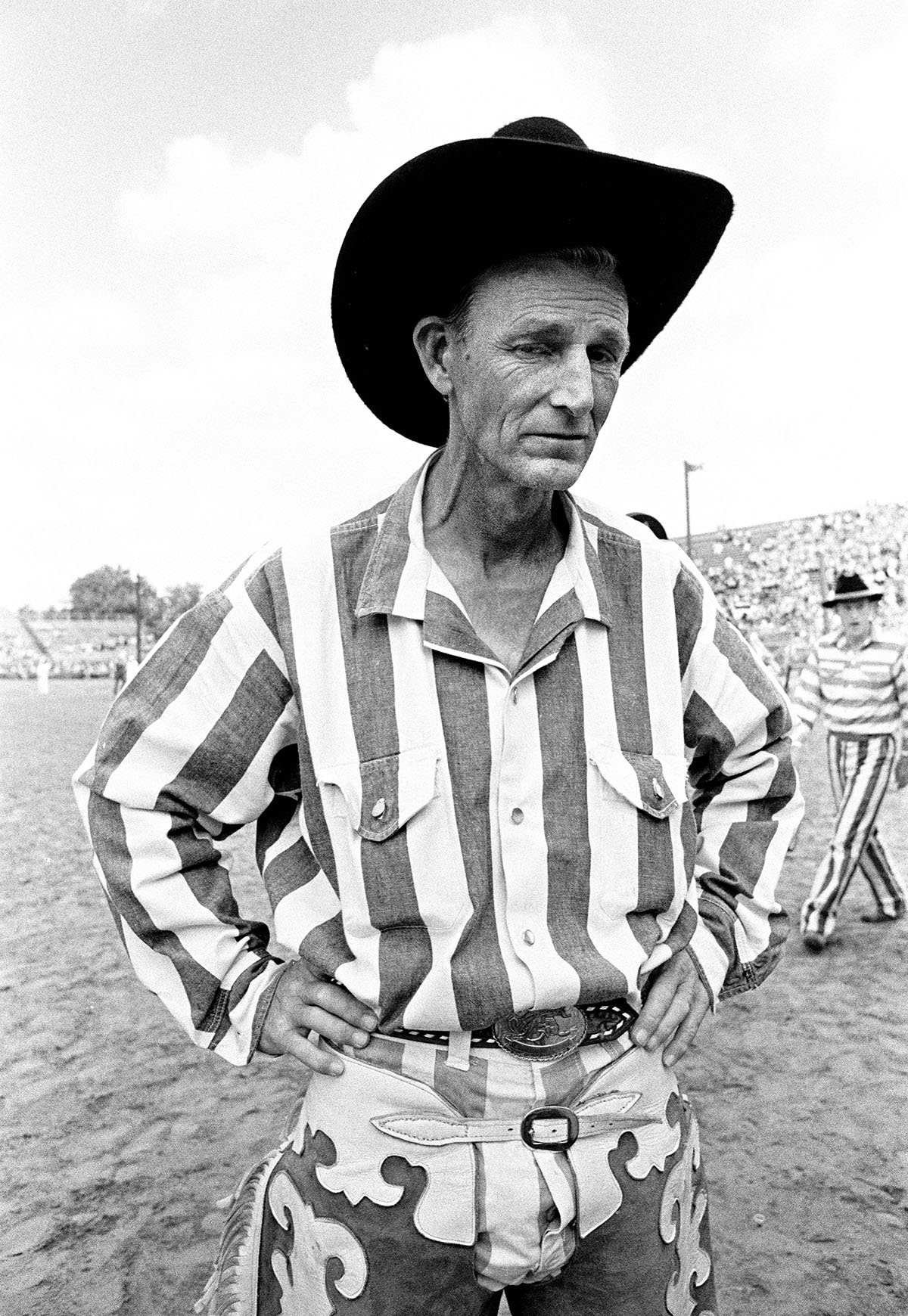

It wasn’t always about competing; in the late 1940s, he made a quick buck warming up the animals before the real cowboys of the Houston Livestock Show and Rodeo took over. But Browning kept notes, watching how the professionals managed to stay mounted while the broncs bucked and tumbled. It wasn’t long before he was a veritable competitor himself. By the time Browning was 44, he was a history-making cowboy—a seven-time winner of the gold and silver Top Hand champion trophy buckle, and by far the best rider in one of the state’s toughest rodeos.

Maybe it shouldn’t have been a surprise. As Houston radio personality “Buffalo Bill” Bailey reminded the crowded stadium just outside the Huntsville Unit, “He’s had all the time in the world to practice.“ It was 1973, and Browning was 24 years into a life sentence for the murder of his abusive father.

Browning, a Black cowboy who grew up around Houston, was just 20 years old when he received his sentence. He became one of hundreds of competitors in the Texas Prison Rodeo, which ran from 1931 to 1986. Billed as “the wildest show of its kind ever staged,” the event was the first prison rodeo in the nation. Alongside entertainment from inmate clowns and choirs, it presented traditional rodeo events—steer riding, bulldogging, goat roping, horse racing, and bronco busting. Several of the prisoner participants had experience riding in major rodeos across the country.

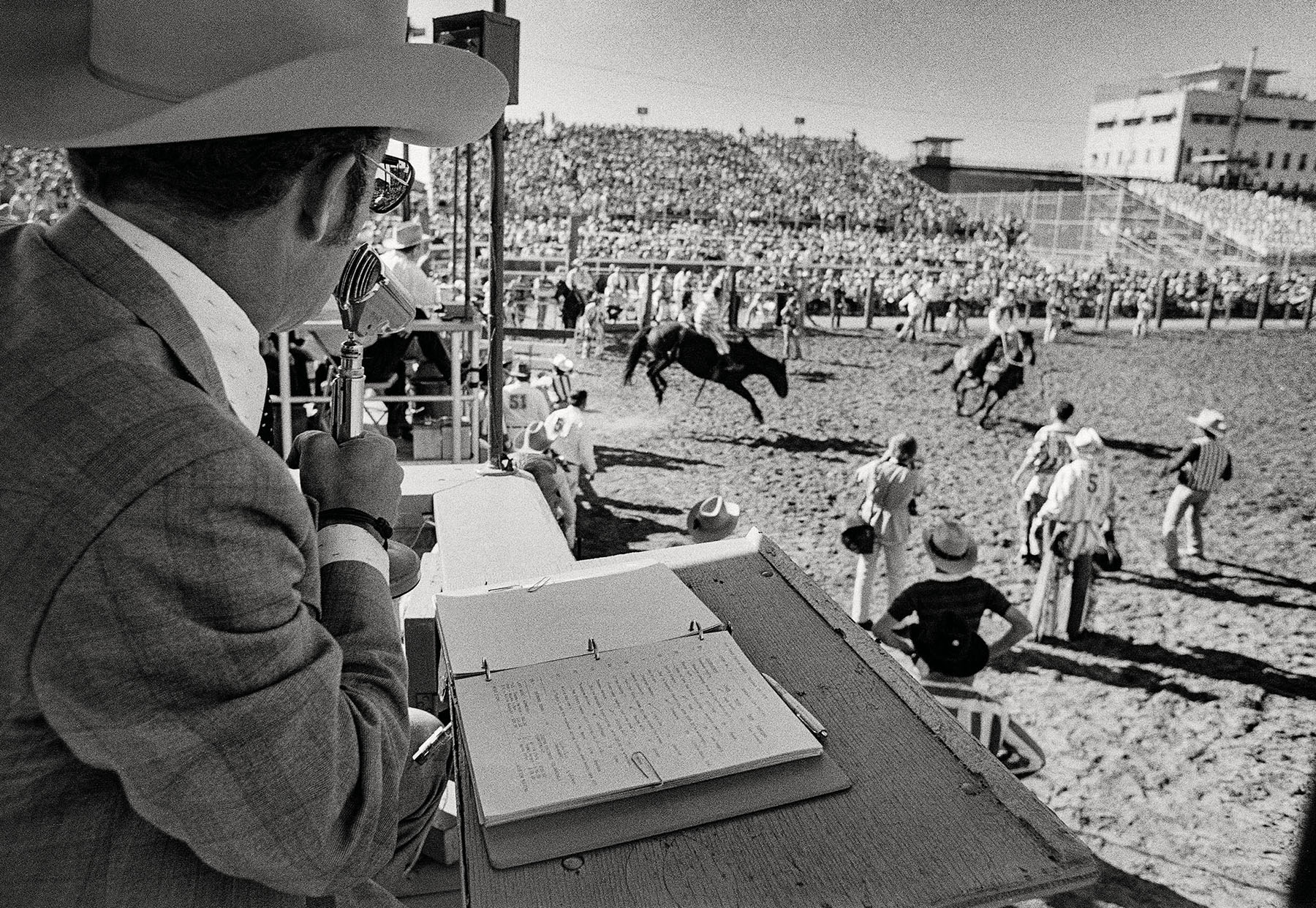

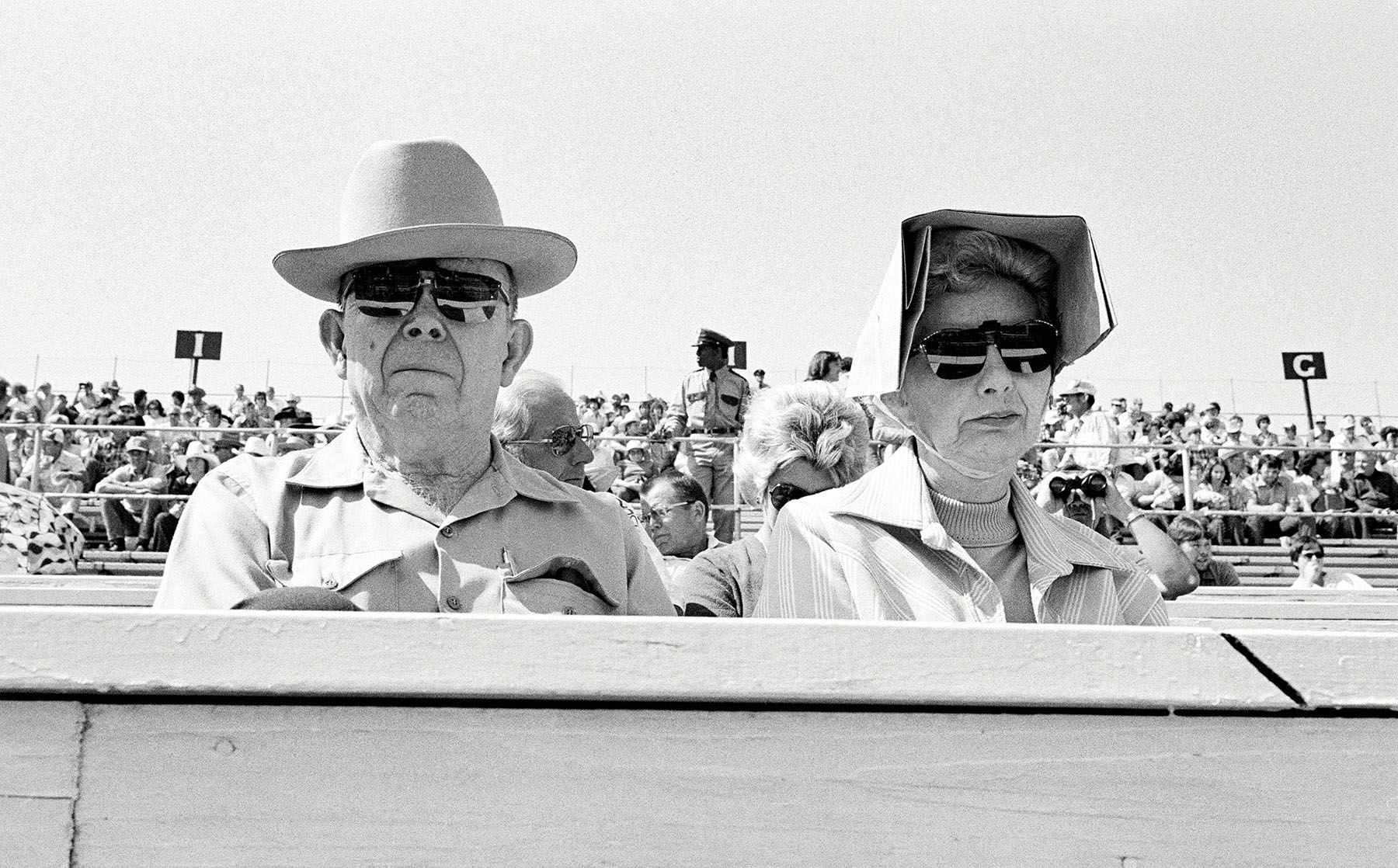

Over its 55-year run, the prison rodeo brought in hundreds of thousands of dollars, attracted spectators from all over the world, garnered press in Life and TIME magazines, and featured performances from George Strait, Willie Nelson, and Dolly Parton. No matter the lineup, though, audiences were mainly there for one thing: to watch prisoners compete as they put their lives on the line.

“This wasn’t just a chance to watch a rodeo,“ says Mitchel P. Roth, a professor of criminal justice at Sam Houston State University and the author of Convict Cowboys: The Untold History of the Texas Prison Rodeo. “This was a chance to watch the convicts. It was a glimpse inside a prison. This was a world people didn’t have access to.”

About an hour north of Houston, the business parks and shopping centers along Interstate 45 give way to dense rows of loblolly pines that lead to the prison town of Huntsville. The students of Sam Houston State University are just down the road from the city’s real claim to fame: the Huntsville Unit. It’s difficult to miss the striking exterior that gave the facility its nickname, the “Walls Unit,” but it’s easy to overlook the smaller trapezoidal structure just outside its red brick borders—one of the only vestiges of the nearly 30,000-seat arena that once housed the prison rodeo.

The roots of Huntsville’s infamous prison system are inextricably intertwined with those of the city itself. In 1848, just a few years after Huntsville’s founding, the Texas Legislature chose the city as the location for the state’s first enclosed penitentiary. While it proved to be critical during the Civil War, it was the prison’s transformation during Reconstruction and into the early 20th century that set the stage for the prison rodeo.

Leading up to the 1930s, conditions throughout the Texas Prison System—known today as the Texas Department of Criminal Justice—were nightmarish. Post-Civil War and Jim Crow laws targeted Black Texans, which introduced an influx of prisoners who were leased out to private companies for labor. As criticism of the practice mounted, the state transitioned to prison-owned farms, which operated in enough isolation to insulate them against widespread condemnation. Without much financial support from the Texas Legislature, prisons weren’t focused on rehabilitating prisoners, let alone providing them with recreational opportunities.

In response to the findings of a 1929 investigative report of the prison system’s conditions, a disapproving Gov. Dan Moody told the prison board, “If I had a dog I thought anything of, I wouldn’t want him kept in the Texas penitentiary under present conditions.”

As the shockwaves of the Great Depression began to ripple through the state, Marshall Lee Simmons, the newly minted manager of the Texas Prison System, began batting around the idea of a prison rodeo. Simmons was hardly in line with prison reformers of the time, but he saw the rodeo as an opportunity to improve the system’s soured reputation with the general public. He also saw it as a way to raise money from taxpayers that were otherwise reluctant to fund prisoner education and recreation efforts.

Simmons faced an uphill battle. He had to convince a community reeling from financially trying times, and notorious for their religious fervor, that it was a worthy use of resources to allow prisoners to indulge in a rodeo. But Simmons, along with the prison’s welfare and entertainment director Albert Moore, Huntsville warden Walter Waid, and prison livestock supervisor R. O. McFarling believed in the vision. After the prison secured the blessings of local preachers to hold the rodeos on the Sabbath, the Huntsville inmates got to work building an 800-seat stadium, chopping down oak timber and breaking ground around a former baseball field. Prisoners voluntarily chose to compete, though they were required to tryout. They weren’t paid to participate, but some competitions offered opportunities to earn petty cash to spend in the commissary.

“Internally, in the prison system, it was a very positive thing,” says Rick Hartley, who served as head of the prison rodeo from 1979 to 1984. “There were a lot of convicts who thought it would be a great opportunity to get away from their normal life and participate as a cowboy. Our wardens and staff thought it could be a breather for them as well.”

It was an inauspicious start to what would become an annual phenomenon. The inaugural event on the first Sunday in October 1931 wasn’t particularly noteworthy—just a few competitors, prison employees, and some curious locals. But it managed to cause a stir. People found the idea of “convict cowboys” exciting, and the audience grew with each subsequent show. It was also the dawn of the Golden Age of the Western, when America’s collective fascination with cowboys and outlaws reached unprecedented popularity. The Rodeo Association of America launched in 1931; Gene Autry, the “Singing Cowboy,” stood on the verge of his first big hit; and the $1.4 million epic Cimarron became the first Western to win the Academy Award for Best Picture. Simmons’ idea had arrived right on time.

“It was unlike any rodeo that I’d ever seen before,” says Larry Callies, founder of the Black Cowboy Museum in Rosenberg. He attended the rodeo twice in the ’70s and says he could clearly tell who were the “city boys” in the bunch.

By then, the prison rodeo had gone all in on spectacle. Within 10 years of its launch, the rodeo welcomed 100,000 visitors annually. Every Sunday in October, crowds lined up outside the arena. A 1940 dispatch of the event in TIME noted that 2,000 to 3,000 people were turned away, while 25,000 others eagerly paid their 50-cent admission to see a “rip-roaring show.” They marveled in particular at the Mad Scramble, a free-for-all barred from most rodeos for being too dangerous. Riders mounted on wild bulls, cows, and broncs raced simultaneously, bucking and bumping one another to the finish line.

By the end of the ’50s and into the ’60s, the prison rodeo pulled top-tier talent to complement the show. In 1959, Johnny Cash made his prison concert debut at the rodeo for $2,000 (roughly $21,000 today) almost a decade before releasing At Folsom Prison. Subsequent headliners included John Wayne, Steve McQueen, Loretta Lynn, and even the astronauts from the Apollo-Soyuz space mission.

There was also in-house entertainment. “Candy Barr,” born Juanita Dale Slusher, was dancing burlesque in Dallas when she made headlines in 1956 for shooting her allegedly abusive husband. Though the charges were dropped, Barr was arrested the following year for marijuana possession and entered the all-female Goree Unit as a kind of celebrity. It wasn’t long before Barr joined Huntsville’s Goree Girls, an all-female prison string band—considered one of the first all-women country bands in the U.S. After forming in 1940, the group rose to fame performing in an auditorium in Huntsville and broadcasting live on WBAP, a radio station in Fort Worth. Prison officials allowed them to perform at the prison rodeo and other rodeos across the country while still serving their sentences.

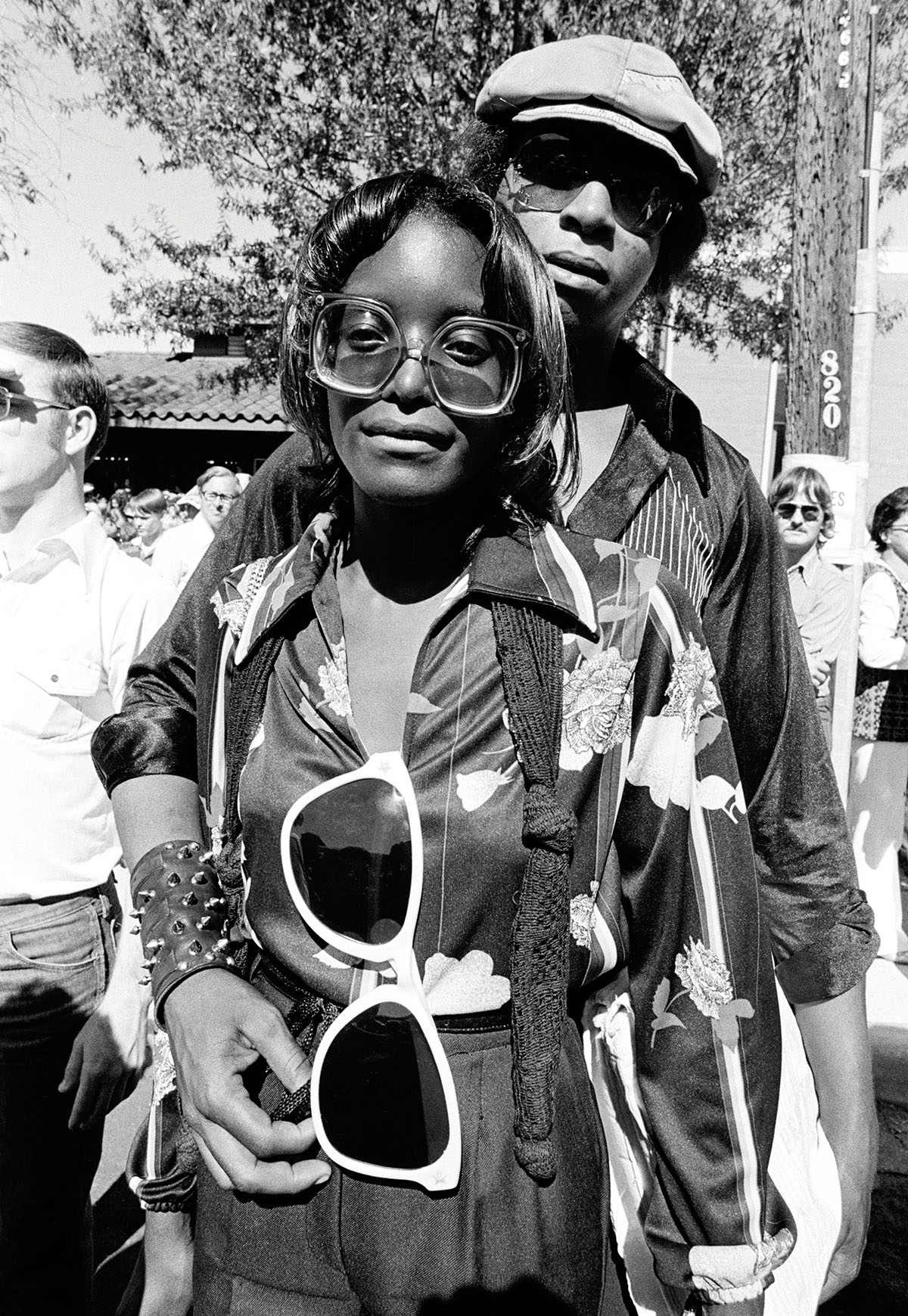

Segregation and discriminatory practices persisted in the professional rodeo circuit well into the ’60s, but at the prison rodeo, Black and white cowboys competed alongside each other. (Black and white members of the audience, however, remained segregated in the grandstands.) “In its early years, it was probably the first desegregated sporting event in the state, if not the South,” Roth says.

Outside of the prison, Black cowboys had met roadblocks for years trying to break into the segregated, predominantly white world of professional rodeo. Callies says he’d seen Black riders get shut out of competitions, denied entry, or scored unfairly. The prison rodeo’s comparatively progressive atmosphere led publications at the time to laud the event as liberating for the Black cowboy prisoners. But Callies saw something different.

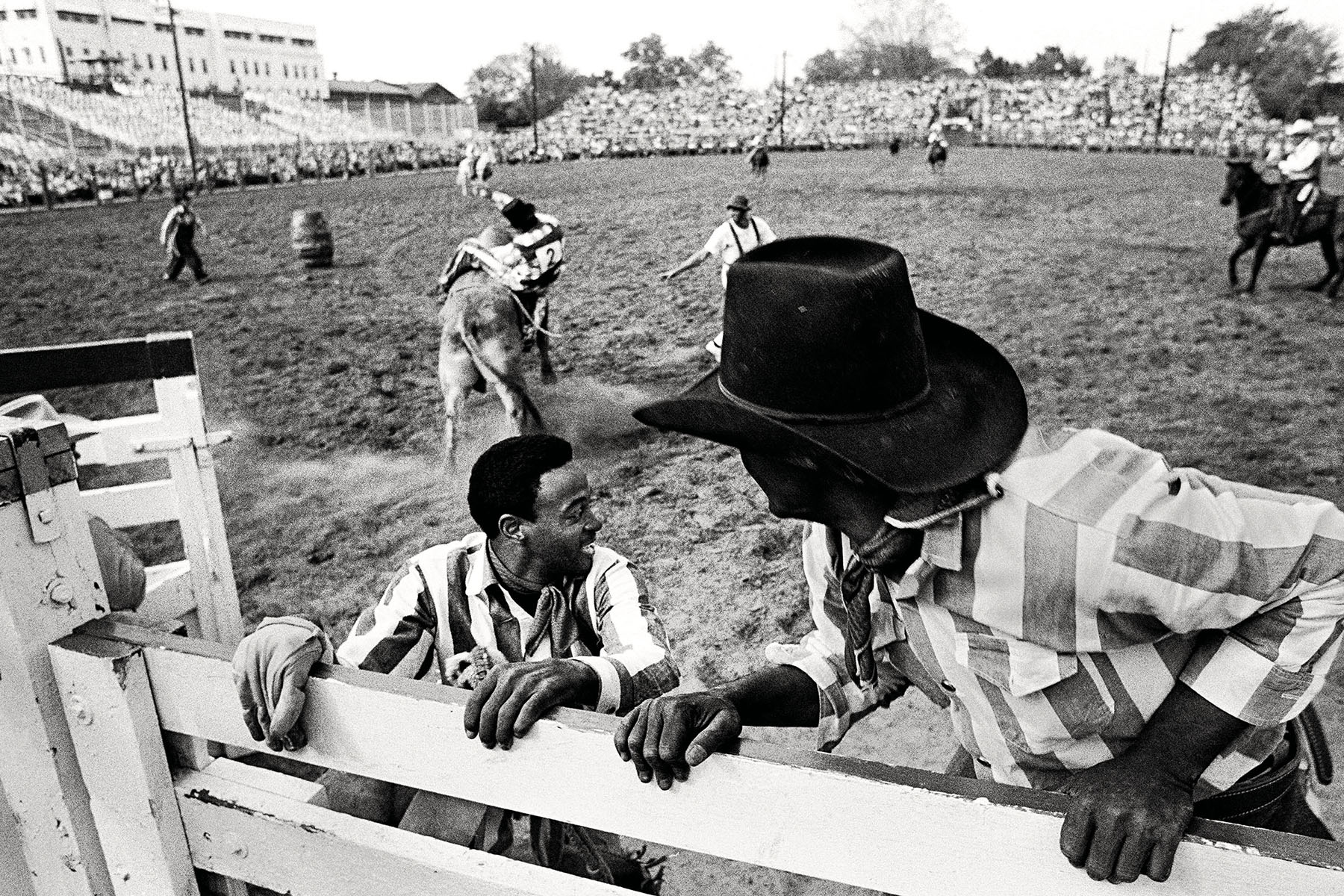

“[The audiences] wanted to see Black men get hurt,” Callies says. “It was no-holds-barred out there, and they made the prisoners do things they wouldn’t do in a normal rodeo. I quit going. It was people getting hurt for entertainment. If it was a prisoner, they didn’t care—but if it was a Black prisoner, they really didn’t care. That’s what drew people there.”

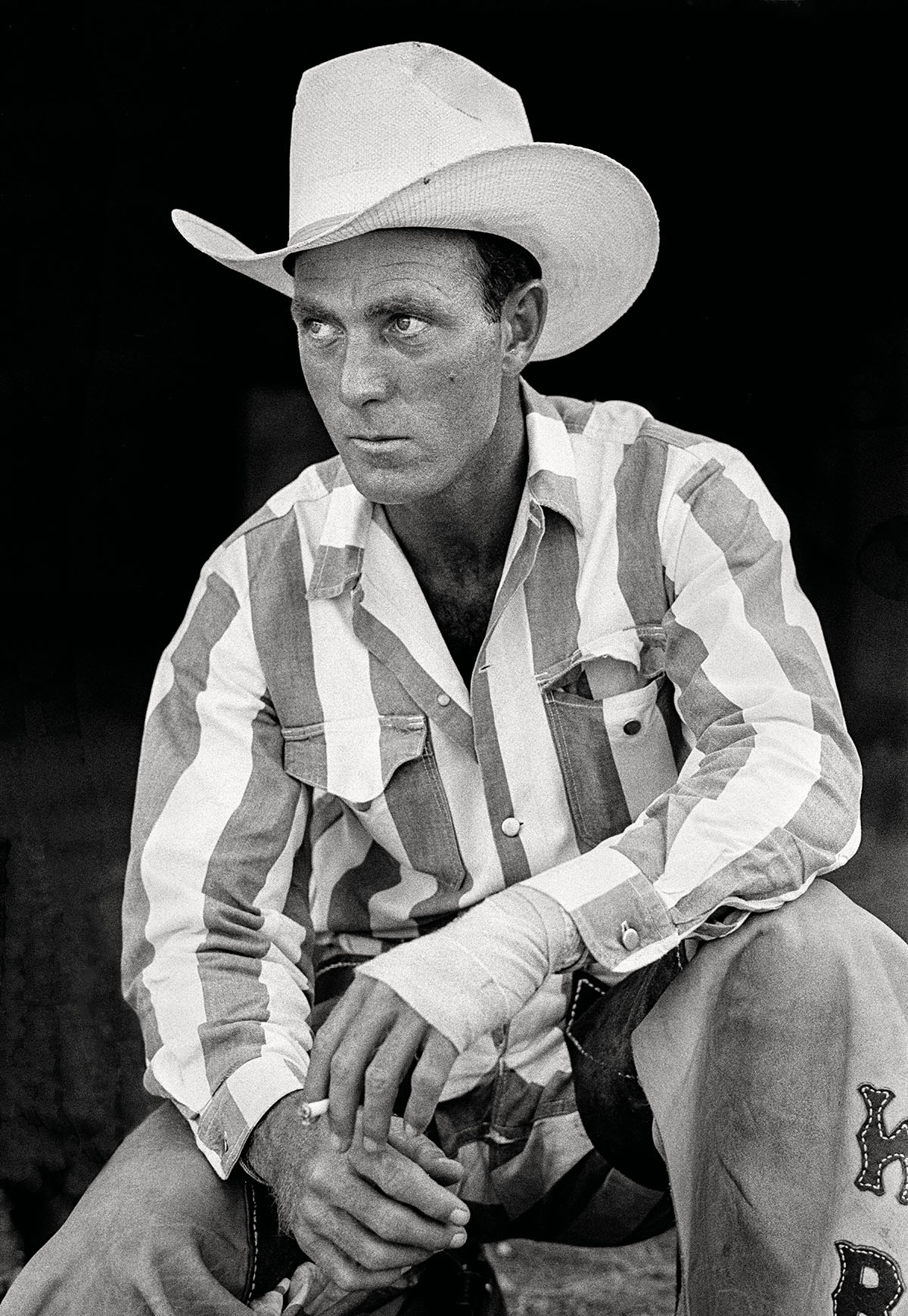

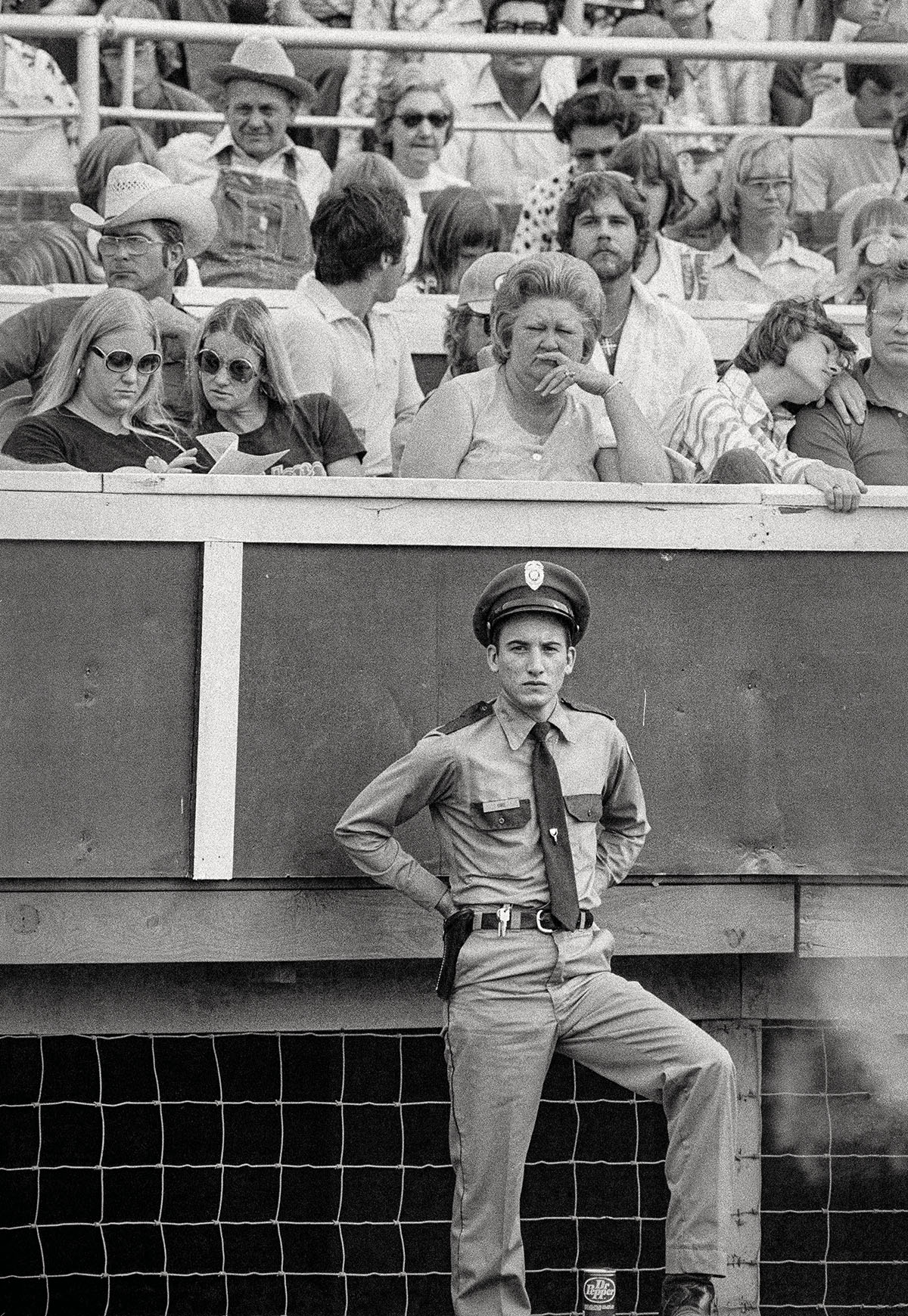

Photographer Bill Kennedy, who began documenting the prison rodeo in the late 1970s as a University of Texas graduate student, says walking into the arena felt as foreign as stepping onto the moon. He took in the cheers, the echoing voice of the announcer, the children enthralled by the bulls, and the hunger in the cowboys’ eyes.

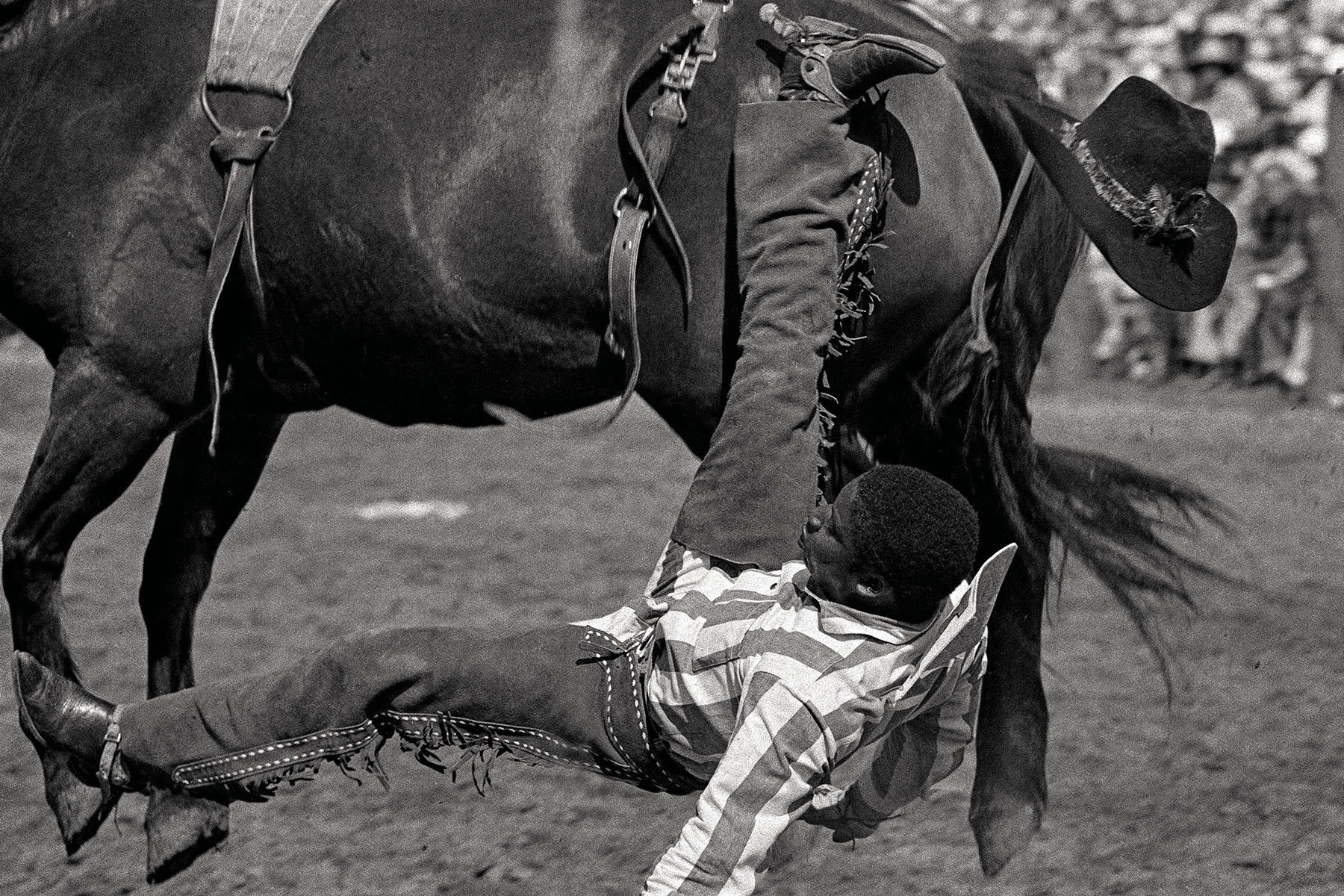

“More than [the money], they were competing for the honor and prestige of it,” Kennedy says. “If you live in an environment where everybody is reduced to a common denominator and you have an opportunity to distinguish yourself, to feel special in any way, I’m sympathetic to that urge.”

He says his first visit to the rodeo felt surreal. With each subsequent visit he gained rapport with several of the rodeo’s frequent competitors. It became harder for him to shake the underlying contradiction at the heart of it all: While many of the cowboys were there for the love of it, or simply for a chance to escape the monotony of their cramped cells, the spectators weren’t there to admire the skill or passion on display.

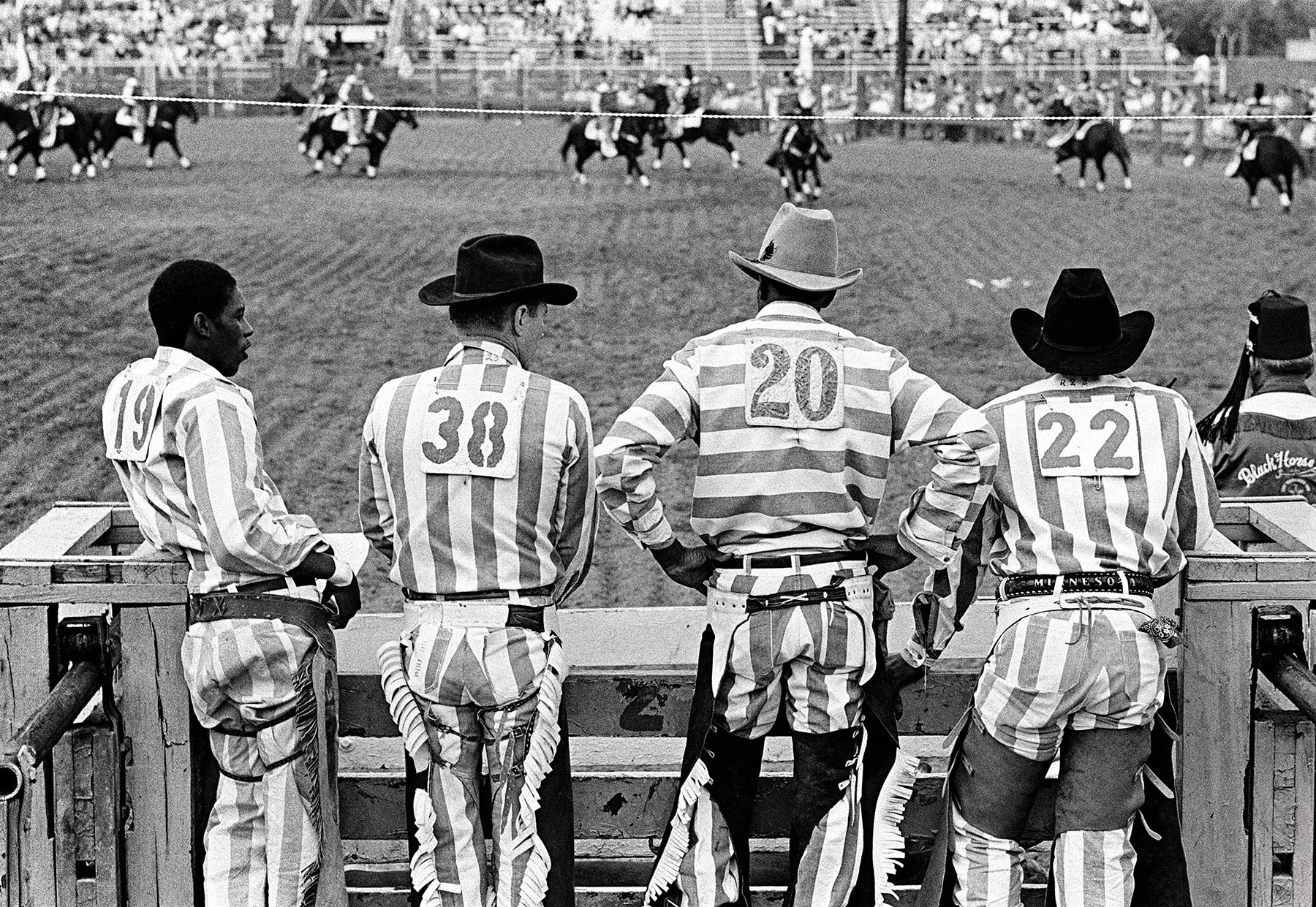

“The inmates hated the term ‘convict cowboy,’ but they loved what they were doing,” Kennedy says. The rodeo was like their New Years, Christmas, and birthday wrapped into one event. But, Kennedy says, this wasn’t a professional rodeo. “It was a show. The inmates had to put on stripes because that’s what the audience expected them to wear. Even the announcer pandered to the crowd, saying all kinds of stuff about the cowboys to play to the audience’s base instincts.”

Though female prisoners had historically been tasked with sewing the black-and-white-striped uniforms the participants competed in, they weren’t allowed to compete. In 1972, however, in an attempt to cut the costs of hiring big-name guest stars, prison rodeo officials allowed women to compete in select events like calf roping and greased-pig sacking.

The change met mixed reviews. In a 1977 dispatch, Texas Monthly writer Gene Lyons observed that the rodeo’s female competitors were less likely than the men to invite their families to watch them compete. One woman, Patricia Alvarado of Galveston, told Lyons she asked her husband not to bring her children with him to the rodeo, saying, “It hurts too much to see them and not be able to get to them and touch them. They don’t understand and it would make them cry.”

A couple listens to the inmate band on the rodeo midway.

Browning was a spectator before he became a competitor. He attended the prison rodeo in 1946—three years before he received his life sentence. He took to the competition immediately, winning his first Top Hand Buckle in 1950 and signaling his dominance in bareback, saddle broncs, and bull-riding events. Roth calls Browning a remarkable competitor—on Oct. 21, 1956, he placed in every single event. In a 1974 interview with Texas Parade, Browning credited his time spent in prison with a softening of his personality and even offered advice to other eager competitors.

He also witnessed the rise and fall of the rodeo, watching as competitors shifted from farmhands and experienced cowboys to unskilled riders and reckless novices.

In its heyday, it wasn’t uncommon for most of the rodeo’s competitors to have some exposure to the rodeo or at least in handling livestock. But as Texas rapidly urbanized in the ’60s and ’70s, the prison rodeo’s competitor pool became increasingly amateurish and imperiled. Injuries sustained over the course of the prison rodeo included chest contusions, broken arms, ribs, legs, and at least one severe neck wound—all of which the prison system was absolved of liability for due to releases signed by competitors.

Spectators had an increasing appetite for events with elements of danger. “It’s like going to NASCAR and hoping to see an accident,” Roth explains. “So rather than having one 2,000-pound bull coming out of the shoot, they would have 10. The more potential for violence, the more popular it was.”

In 1963, officials found the peril they were looking for. Borrowing from the Oklahoma Prison Rodeo, they introduced the Hard Money event in which a tobacco sack stuffed with cash—sometimes up to $2,000—was secured between the horns of a Brahman bull. Forty competitors outfitted in red shirts ran through the arena in a mad dash to snag the loot. Callies recalls seeing a few competitors get hurt—one trampled by a bull was hauled off in an ambulance. “That was part of the entertainment for some people,” Callies says. “I hate to say this, but they were like circus monkeys. It wasn’t about skill at all; it was about the danger.”

In the rodeo’s final years, critics called out its transparent attempts to draw positive coverage and distract from a 1972 class action lawsuit against the Texas Department of Corrections. A 1978 article from The New York Times covering the lawsuit described the Texas prison system as a “harsh picture of brutality, overcrowding, and inadequate medical care.”

By 1986, the rodeo’s future was shaky. Though the event still drew a sizable crowd, it was well past its prime. Coupled with changing cultural tastes, the sheer cost of putting on the show—paying for entertainment, hiring police officers to direct traffic, factoring in overtime pay for prison employees, and funding stadium maintenance—spelled its doom. “It was a moneymaker when cowboys were in fashion,” Roth says.

With rodeos falling out of favor, event organizers had difficulty pulling the same marquee talent that once drew large crowds. “I think there were a lot of factors that [contributed to its demise],” Hartley says, “but in my opinion, it was a travesty to see the prison rodeo go away.”

Over the decades, explanations for why the rodeo was ultimately scrapped have varied, with most citing the cost of repairing the stadium. “For years, the prison system wanted to get out of the rodeo, and the crumbling stands finally gave them the chance,” Roth explains. When the Texas Board of Corrections weighed the decision on whether to continue, some board members argued they could be liable for any rodeo injuries and questioned the legality of having inmates sign liability release forms.

“They were worried about being sued,” Roth says. “Without enough insurance coverage for the prisoners and the fans, it was just asking for a problem.”

Despite Browning’s prominence in the rodeo, his life after the rodeo is mostly a mystery. He died in prison in 1997, with no visitors on his list. His prowess in the sport had merited several mentions in local and national newspapers throughout his life, but in death, he was just one of many prison rodeo ghosts. While the rodeo might’ve offered prisoners a brief chance at glory inside the prison, it didn’t extend to their lives outside of the event. As Lyons noted in Texas Monthly, “Nobody ever comes back as a spectator.”

The prison rodeo’s legacy is a complex one. Critics question whether the event was more exploitative than beneficial. It also inspired similar events in Oklahoma and Louisiana, which is home to the only public prison rodeo still in operation. Launched in 1965, the Angola Prison Rodeo in Angola, Louisiana, draws similar critiques and concerns today . Despite the controversies, attempts to bring back the prison rodeo in Texas have been discussed as recently as a few years ago. State Rep. Ernest Bailes filed a bill to revive it in 2019, but the idea never gained traction.

The Texas Prison Museum in Huntsville details the history of the state’s prison system. Artifacts from the Texas Prison Rodeo, a pistol taken from the car of Bonnie and Clyde, and art from local prisoners are on display.

491 Hwy 75 N., Huntsville

936-295-2155;

txprisonmuseum.org

In 1982, a reporter from the television program Southwest International News Service attended the rodeo to interview competitors. An archival video segment features an interview with an inmate named Rusty Huff, a 59-year-old cowboy from Pampa who had been participating in the rodeo for the past 12 years.

“Do you feel freer when you’re doing this?” the reporter asked.

“Yessir,” he said, shaking his head, the silvery brim of his hat tipped low. “I do.”

Huff won that year’s Top Hand title—his second time earning the distinction. It was his final ride in the prison rodeo; he finished his sentence six months later. For 15 years, the rodeo had been more than an opportunity for Huff to get out of his cell; it was a chance for him to reconnect with something he loved. As the Eagles’ “Desperado” played from stadium speakers, he told the interviewer the first thing he’d do upon release was go home and get back to cutting horses. In 2014, when Huff passed away in Pampa at the age of 79, his obituary listed him as a lifelong cowboy.

The prison rodeo ended much like it began, without fuss or fanfare. On Oct. 26, 1986, the last event was held, featuring a performance by mother-and-daughter duo The Judds. In 2012, the Texas Department of Criminal Justice razed the arena, citing safety hazards. The grounds that once staged Texas’ wildest show is now a parking lot.

“People came from all over the world to see the rodeo, and if you walk by the prison now, you would never know it existed,” Roth says. “But it would be a shame for people to forget it.”