Lights, Camera,

The small Texas town that defies easy stereotypes

has captured Hollywood’s attention

I used to pass small towns and feel sorry for the people who lived in them. What could you do there? Who could you be? Much of modern life was such a race to be exceptional—the biggest house, the most followers—that I felt a hint of sadness staring at those rusty warehouses and abandoned shacks off the highways of rural Texas, a land that time forgot. But something happened as the technology age unfolded, with all its virtual bustle and ambient anxiety—and I became a woman who sniffed around small towns looking for a hit of what they had. A slow-pour pace, a sense of community, something called affordable rent.

That’s how I wound up spending time in Corsicana, a town of 25,000 people an hour south of Dallas. The more I wandered its quaint contours, the more I came to feel not sadness for the people who lived there, but envy for their lifestyles. Contrary to my preconceived notions, there was plenty going on: an artist residency, a hit reality show, and a police chief making movies.

“I wrote a Western last week,” said Robert Johnson, the first police chief I ever met with his own Internet Movie Database (IMDb) page. Over the past decade, Johnson has acted in more than 30 TV and film productions. More recently he’s cracked his knuckles as a producer and screenwriter. When we met, he was eagerly preparing for the filming of his Western, fittingly called Corsicana. Johnson’s unusual career in law enforcement and entertainment has helped bring more than a dozen projects to town in the past few years, including a drama called Warning Shot with David Spade and a B-movie satire called American Zombieland, the climax of which involved locals descending on the historic downtown as mobs of the undead. But Johnson is only one of many people re-imagining what it means to live and thrive in rural Texas, a part of the country that is transforming from a land time forgot into a land of opportunity.

Corsicana’s rise in the 21st century is a story of small towns, which are making a comeback as the blinking metropolises grow more clogged, expensive, untenable. You could say the internet started it, unlatching us from any fixed geographic spot. But Chip and Joanna Gaines turned the trend into a revival, building an empire in Waco by showing folks how to transform those abandoned shacks into neo-rustic dream homes. A new generation was rediscovering towns like Lockhart, Brenham, and Marble Falls long before the pandemic and the rise of Zoom made their own compelling arguments against urban density. As I wandered the wide avenues of Corsicana, I noticed how easy it was to socially distance, as though staying 6 feet apart was not a public health measure but a way of being.

Until recently, Corsicana had been known for one thing: fruitcake. Collin Street Bakery is home to the indomitable dessert and, improbably, the setting of a made-in-Hollywood baked good scandal featuring an unassuming accountant who embezzled millions. A movie about the crime, starring Will Ferrell, was in development, although its current status is unknown. The city’s reputation leveled up in early 2020, when a Netflix reality series called Cheer tumbled into the zeitgeist. The compulsively watchable six-episode show—it came to town independently of Johnson’s efforts—took viewers through a nail-biting season with the top-ranked Navarro College cheerleaders, whose injuries and feats of daring show how cheerleading has evolved from sideline spectacle to rigorous competition. With its gravity-defying basket tosses and hard-luck tales of kids vying for greatness, Cheer was like Cirque du Soleil meets Our Town. The show was a surprise hit, garnering three Emmy wins and turning its hard-driving but maternal head coach, beloved Corsicanian Monica Aldama, into an overnight sensation who waltzed her way to 10th place on Dancing with the Stars while continuing to coach her famous squad.

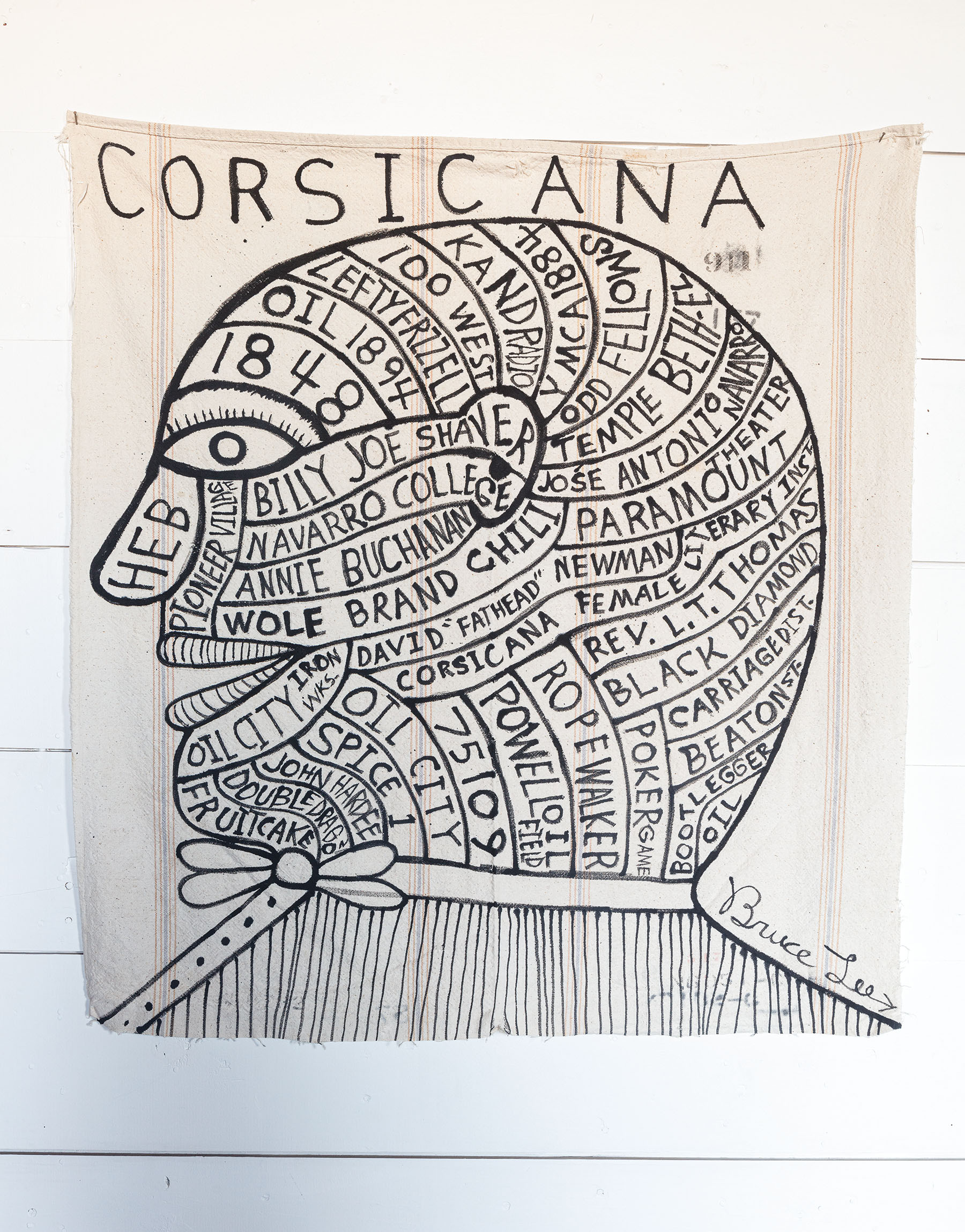

Surprises have long been part of Corsicana’s history. A man drilling for water struck oil in 1894, turning a land of cotton fields into the first oil boomtown west of the Mississippi. The railroads had arrived in 1871, making for a bustling turn-of-the-century marketplace where enterprise and characters collided. A boy named Lyman T. Davis dragged his wagon past the saloons to sell bowls of chili for 5 cents, a business that became Wolf Brand Chili. An oil field worker fathered a singing cowboy named Lefty Frizzell, whose honky-tonk yodel influenced generations of country performers including Willie Nelson, who recorded an album of cover songs. (The Lefty Frizzell Museum at Pioneer Village is one of the city’s hidden gems.) In 1884, a one-legged tightrope walker strung a high wire across the main street only to tumble to his death and into Texas lore. The unidentified man is buried in a grave under the name “Rope Walker,” though a recent book claims his name is Joseph Berg. When I expressed confusion about this story to a local—why was a one-legged man walking on a high wire across downtown again?—he answered in a soft twang with a wave of his hand. “Well, he had to sell his potbelly stove.”

The sliding-door moment for Corsicana came in 1919, when city leaders, hoping to retain the town’s cozy charm, declined to let Magnolia Petroleum Co. build two 29-story skyscrapers in downtown. The company, which became Mobil Oil, moved to Dallas, along with much of progress. Corsicana still had wealthy oil families whose patronage shaped the town, but the urban boom that transformed Texas in the latter half of the 20th century left Corsicana largely untouched. The rare success story was Collin Street Bakery, whose pecan-rich DeLuxe Fruitcakes were a mail-order sensation, becoming both late-night punchline and holiday staple. But the downtown area fell into disrepair, a slump that spread through much of rural America. It took decades to revitalize the downtown into a place where out-of-towners might like to venture.

Downtown Corsicana called to me when I pulled off a drab stretch of Interstate 45 one Sunday on my way back home to Dallas from a friend’s ranch in nearby Streetman. I sauntered along the red-brick storefronts that reminded me of 20th-century Americana, with new and old murals seemingly made for the Instagram age. The main stretch of Beaton Street was spookily quiet, the only noise the lonely blare of a train passing through. I could have been the only one there, although in fact I was learning a valuable lesson about small Texas towns: never visit on Sunday. Everything’s closed.

A statue of local radio pioneer Dick Aldama, Monica Aldama’s father

That sense of having stumbled onto something unique is a common experience here. “It felt like limitless potential to build a world,” said Kyle Hobratschk, a young artist who struggled to find an affordable wood shop for making furniture while living in Dallas about nine years ago. He heard about a space in downtown Corsicana, a leaky, three-story, 19th-century former Odd Fellows lodge that was equal parts decrepit and magical. He bought it.

He called the place 100W—after the address (100 W. 3rd Ave.) and because he liked the notion of “going west” to build—and spent years restoring it to a dreamy marvel of natural light with huge lofts. He didn’t need 11,000 square feet of space, so along with a few other local artists, he hatched a plan to build a residency that has now hosted a hundred visiting artists and writers from places like Iceland, Scotland, South Korea, Argentina, Germany, and New York. Residents get to experience a part of the state that might not be as familiar to tourists as Marfa and Austin but still matches the Texas of the imagination. Cattle ranches, empty mills, rolling prairies. “The art world can be snobby and insular,” Hobratschk said. “We can introduce our Parisian resident to an 80-year-old cowboy.”

The residency’s location in a mostly conservative town offers a bridge into another America for the characteristically liberal-minded, a connection that has been hard to make in a time marked by echo chambers on both sides and the impulse to block-delete anyone who disagrees. Small towns have not always been celebrated for their accepting natures, but what I heard from locals on subjects like politics, sexual orientation, or religion was that it’s hard to hate someone you see at the grocery store or chat with on the street. The old complaint about small towns was: Everyone knows you! Now, in the vast anonymous internet age, when social media has turned into a battleground and flattened so much of human complication, the words sounded soothing to me—a promise that your soul could not be swept aside. Everyone knows you.

The history of Corsicana is not without complication. Councilwoman Ruby Williams remembers going to school before integration, which came to Corsicana in 1970. “I had to walk to school 30 minutes every day, whereas my white counterparts rode the bus and said derogatory remarks as they passed,” she told me in a smooth contralto, as we sat in the Martin Luther King Jr. Center on the east side of town. Williams has represented the mostly Black and Hispanic neighborhood for 16 years. Corsicana is fairly diverse. White residents make up 40%; Hispanic, 35%; and Black, 19%. But like so many other cities, the town has suffered a painful racial divide. “Things are better now,” Williams said, “but they’re not where they ought to be.”

Williams’ father was a minister and sharecropper, and she remembers picking cotton when she was 4 and weighing the bag on her daddy’s scale—two bucks a bag. “I thought I was going to move away,” she said, and sighed. But life happened. She got married, had a family. Like many people I spoke with, she had a sense she might be useful in her hometown. She showed up for our interview straight from church, wearing a sharp white suit and dangly beaded earrings that shimmied when she moved her head. “How old do you think I am?” she asked at one point, with the confidence of a woman who is going to win this game. I guessed she was in her 50s. “Seventy-six,” she told me, and I whistled.

Over those decades, Williams has seen progress, albeit slow. Lately, one of the projects she’s helped oversee is the creation of a bronze sculpture of G.W. Jackson, a Black principal whose school was so excellent in the early 1900s that, as the story goes, kids rode from Dallas to attend. Bronze statues around town are a Corsicana trademark, one of the ways the town tells the story of itself, but until now there has not been a statue of an African American. The G.W. Jackson Multicultural Society commissioned one, tapping artist Spencer Evans, a Houston native, to create the sculpture. It captures Jackson in a powerful posture, hand reaching out. A video of the sculpture in progress, shared on the Corsicana Daily Sun’s Facebook page, got thousands of views.

“He wanted our children to tap into a better life,” Williams said. “Back then, our children could only work in the cotton field or Oil City Iron Works. There wasn’t even fast food.” But Jackson believed in education, and so does Williams. “We need to know where we came from, to know where we’re going.”

On an unusually chilly day in September, I drove along a winding farm road to an old white church and a cemetery where Johnson was filming his Western. I never could get my head around a police chief making movies. When I asked him what folks in the department thought about it, he said, “I don’t hunt, I don’t fish, I haven’t watched TV in seven years. So, what other people think of what I do on my time off? Well.”

At a moment when trust and communication between police and ordinary citizens have been strained, Johnson told me his side hustle was a bonus, not a detraction. “You have no clue how many young people will not talk to Robert Johnson the police chief,” he said, “but will run across the parking lot, call, or drop by to speak to Robert Johnson the actor, writer, producer.”

Johnson’s law-enforcement career began in Corsicana in the late ’80s, but by the ’90s he was working in Dallas, where he became police chief of Methodist Hospital. A friend kept nudging him to try acting. He has one of those faces. Strong, weather-beaten. Like Arnold Schwarzenegger crossed with Jon Voight. But he also has one of those back-clapping Southern personalities that could work as a sheriff, a salesman, and a lawyer, all of which he’s played. Ten years ago, he landed a cameo on the short-lived Fox TV show Lone Star. The bug bit. He retired from Methodist Hospital in 2016 and planned to act full-time, when the Corsicana chief of police job came up and he spotted an opportunity. “I thought: Why not? I’ll end my career where it started.”

In 2016, Johnson spent weekends in Bakersfield, California, working on the movie Trafficked, a thriller starring Ashley Judd. The varied topography there makes it a popular filming location, and it struck him Corsicana could provide something similar: lakes, cattle ranches, a historic downtown that could look like an old mining town or Anyplace, USA. He partnered with local business leaders, including Jimmy Hale, who owns the Across the Street Diner, and Amber McNutt, part of the McNutt family that owns Collin Street Bakery. About a dozen projects have come to town from as far away as India and Russia. A Bollywood production was set to film during the summer, but COVID-19 temporarily shut that down.

Corsicana, however, is continuing apace. Johnson’s new film project tells the story of Bass Reeves, the first Black lawman of the West. Reeves’ life was riveting. Born in 1838, he escaped slavery and lived among the Cherokees, Creeks, and Seminoles. Later, he was recruited to work for the police in Arkansas and Oklahoma, logging 3,000 arrests and becoming the first Black U.S. deputy marshal.

“This guy is the Black Panther of law enforcement,” said TV and film actor Isaiah Washington, who is starring as Reeves and more recently took over as director of the movie. Washington wears a navy Union Army jacket, and his gray-dappled beard has enormous fluffy mutton chops.

If you think filming a movie during a pandemic might be complicated, you would be correct. “This is my sixth test,” said producer Ryan DeLaney, as he coughed into his elbow, per instructions, before getting his mouth swabbed. Some cast and crew members had to be replaced when they didn’t want to fly, and the Screen Actors Guild has strict limitations on food, sanitizing, masking, and social distancing. Johnson said the filming costs about 35% more during COVID-19. “I have to be cognizant of writing in a way where we have the fewest actors or crew members in the area,” he told me.

There are also strict rules for on-set visitors, which is how I wound up observing across the dirt road, near barbed wire in a spot called Zone B, which might as well have been called “you can go home now.”

I headed back to Dallas on I-45, but as I passed signs for downtown Corsicana, I pulled off to make one last stop. Despite my many visits, there was one view I hadn’t gotten, and I texted Hobratschk to see if he could help. “What time might be ideal?” he replied, ever the gentleman. Neighborly visits, another small-town bonus.

Ten minutes later, Hobratschk walked me up a narrow, winding, handmade staircase and lifted a latch that opens onto the broad rooftop of 100W, a view he had told me about. Both of us stepped to the perimeter to take in the full panorama: a sweeping view of a small Texas town. The buildings looked like pieces of a puzzle slotting together: the renovated Palace Theatre, the railroad, and Grace Community Church. I have stood on many tall rooftops marveling at epic views, but this was the opposite. How human-scale, how easy to wrap the mind around.

Hobratschk told me he writes checks and walks them over to the water company, one of those rural inconveniences he’s come to enjoy. It sounds nearly Paleolithic in a day of Venmo, but he likes writing the numbers in the box and walking the money to its next location, earning each step of the transaction.

“The more I’m here, the more I think this is how people should be living,” he remarked.

I wanted to stay for the sunset, but you know, modern life. I needed to beat the traffic.

—

This story was produced in partnership with Stranger’s Guide. The quarterly magazine is devoted to exploring destinations around the globe. Read more about our partnership.