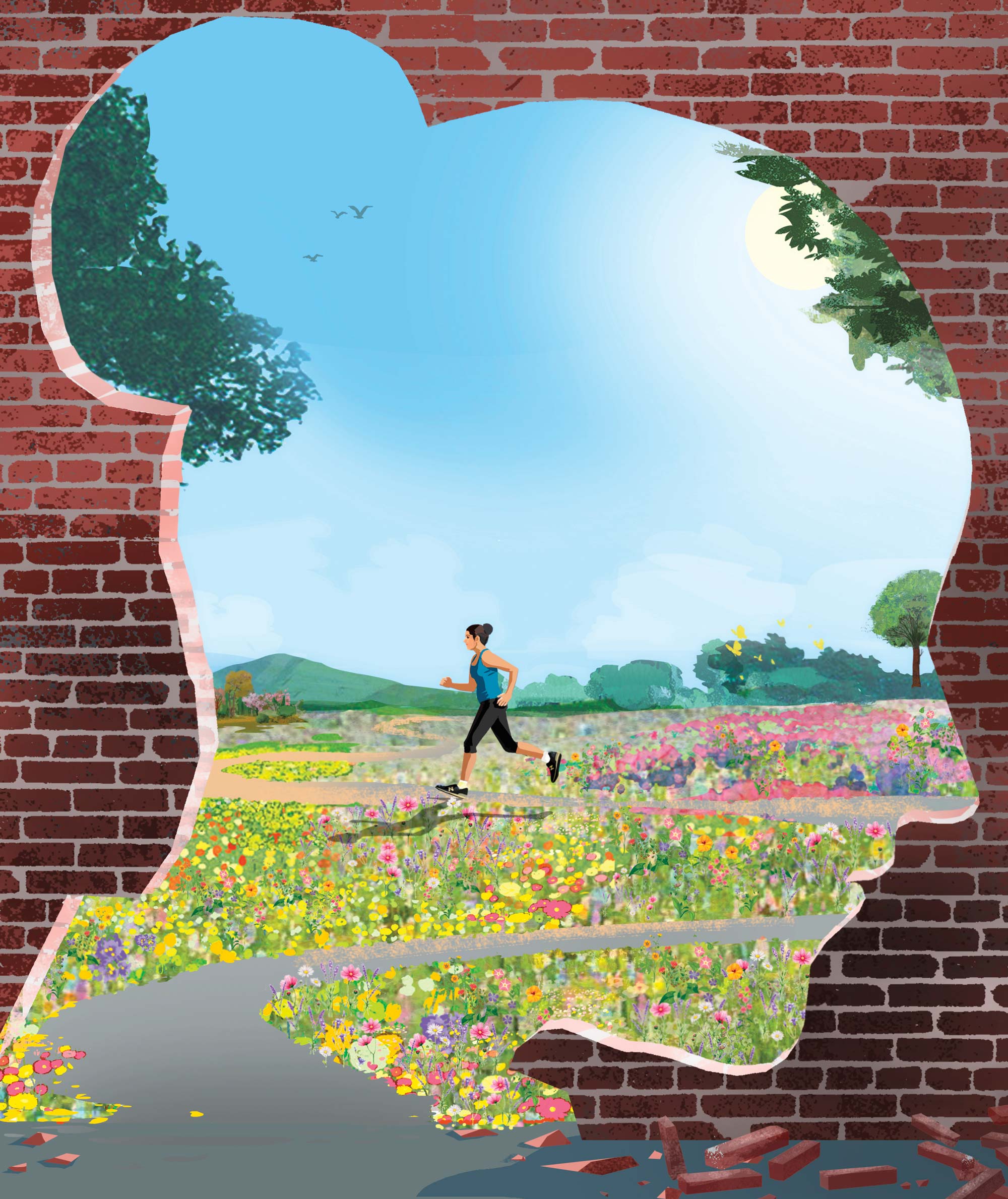

Each morning I run, I begin as the sun rises. If the sky is clear, the sun’s golden rays send shadows and light across the nodding tips of tall native grasses. Before me, the prairie transforms into a scattering of coins, winking, disappearing, and winking again. A red-tailed hawk lifts up from the stands of grass and arcs its way up to one of the nearby rooftops, agile and acrobatic in its movement.

Despite running along this trail for 10 years now—through the rotation of seasons—the wild beauty of the Mueller Southwest Greenway in east Austin startles me on a daily basis. I’m struck it exists a mere mile from my home in Windsor Park, just across 51st Street, in the ever-growing Mueller development. The area is a dense community of new urbanism with much of the neighborhood featuring attractive residential homes as well as several shopping areas, commercial buildings, and the Dell Children’s Medical Center. Downtown and the Capitol building are only 4 miles away. All of this wildness and natural splendor in the middle of the city.

During the spring, the wildflower show is particularly dazzling, its explosions of color like a glorious Monet masterpiece: the sturdy heads of bluebonnets with their elegant fluted leaves; the whimsical pink of evening primrose that crawls down the side of a hill and underneath the canopies of live oaks and cedar trees; the drooping yellow-and-amber petals of the Mexican hats. There is one particular stretch of field that provides the most beautiful spectacle; ironically, it sits between the loading docks of the Best Buy and Bed, Bath & Beyond, and the constant vehicular hum of Interstate 35. On the other side of the highway, there are signs for the Deluxe Inn, Chuck the Mechanic, and an adult-entertainment store.

During the spring, the wildflower show is particularly dazzling, its explosions of color like a glorious Monet masterpiece.

This is what makes me appreciate this particular sweep of blooming flowers even more—how it lives side by side amid the persistent traffic, big-box stores, and slipshod storefronts. And I am reminded of a well-worn quote by Lady Bird Johnson, who is forever associated with Texas wildflowers and the preservation of natural beauty throughout the state: “Where flowers bloom,” Johnson was fond of saying, “so does hope.”

•

Recently, I watched a home movie of Lyndon and Lady Bird Johnson that is archived at the LBJ Presidential Library here in Austin. It’s from 1943, and Johnson is lying in an endless field of bluebonnets along Manor Road, next to the city’s old airport, her elbows propped up against the ground. At the time, the field was a part of the 20-acre farm of Col. Roy Aldrich, who served in the Texas Rangers for 32 years. In the voice-over of her familiar East Texas accent, Johnson says: “Notice the handsome live oak trees.” Her head cocks to one side, a dimple punctuates her left cheek. An occasional white bluebonnet dots the expanse of blue. Passing clouds obscure the sun’s brightness. “There am I in my very native habitat,” she says, taking in the scent of a bluebonnet bouquet that she holds in one hand. The expression on her face is a knowing wink, a subtle smile, a sort of peaceful contentment. “There is always a breeze in April,” she continues. “It’s a windy country.”

Seventy-five years later, the field where Johnson posed amid the bluebonnets—in her “very native habitat”—is now a part of the Mueller Greenway.

President Lyndon B. Johnson hands Lady Bird Johnson a bill-signing pen after signing the Highway Beautification Act on Oct. 22, 1965. Photo: Frank Wolfe/LBJ Library

I’ve been a runner for most of my life. In elementary school, I earned multiple ribbons in the 50-yard dash during the annual field day. On weekends and after school, I often ran the dirt trails that bordered a nearby lake. On its muddy banks, I tried to catch crayfish, or made necklaces out of the stems and blooms of white clover. During my teens, I ran along the narrow footpaths that threaded the wooded hillside of the grounds of Cranbrook, in southeast Michigan, where I attended high school. I found refuge in my strides, long and swift, the brisk air against my face. In early spring, I ran past a gentle slope populated with thousands of butter-yellow daffodils. The sight of the flowers, their trumpet-shaped heads lifted toward the afternoon sun, always restored a sense of optimism. A new beginning. A recalibration to the present moment that I didn’t even realize was about to pass me by.

Running was something I picked up from my mom. In 1978, after Olympic gold medalist Frank Shorter ignited a national jogging craze, my mom trained for the Detroit Marathon, running at all hours. I remember riding on my metallic-green Schwinn alongside her on the dark, quiet streets of our suburban neighborhood. Unfortunately, my mom injured her knee and didn’t end up racing; instead, we handed out Dixie cups of water to passing packs of competitors on East Jefferson Avenue. Ultimately, my mom spontaneously ran the last mile of the marathon with a lanky, dark-eyed runner, encouraging him to cross the finish line on Belle Isle when he wanted to quit. Later, he became her boyfriend—Mr. Runner, as I thought of him. He was one of the many boyfriends who offered my mom temporary happiness, until he didn’t anymore. As I moved into adulthood, I began to recognize this pattern with my mom, cycling through boyfriends and three husbands, with the early days of courtship producing glints of joy and contentment that would extinguish just as quickly.

In my 20s and 30s, I ran on the bridle path in Central Park, in Manhattan. Each season offered a different version of natural beauty—the autumnal kaleidoscope of browns, oranges, and yellows; the freshly fallen blankets of snow, like sparkling troughs of ice cream that bordered the winding pathways; the pink-and-white canopy of cherry blossoms that encircled the Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis Reservoir; and during the summer, the dappled sunlight filtered through the dense emerald treetops. I remember, during the shock-filled days that followed 9/11, running amid the multitudes of New Yorkers seeking solace in the immense green space of the Great Lawn. The sky was cloudless, and a sour burning smell hovered in the air—an ever-present reminder of the smoking ruins on the southern tip of the island.

•

Once I moved to Austin in 2004, I ran the trail that borders Lady Bird Lake (then called Town Lake) and later the crushed-granite paths of the Mueller Greenway. Nowadays I take photos with my iPhone and post them to Instagram as proof of the abundance of nature’s ever-changing performance. My appreciation for the trails and public green spaces of my adopted city led to my growing awareness of Johnson and all she did to preserve the environment in both Texas and the rest of the country.

In 1963, Johnson arrived in Washington with her husband and seized the opportunity to promote the conservation effort. She mobilized individuals to improve their surrounding physical landscapes by seeding millions of flowers in her new city of Washington, D.C. She also encouraged individuals to simply pick up after themselves. Ultimately, the Johnson Administration enacted about 200 environmental laws, including the Wilderness Act and the Clean Air Act. Johnson’s crowning achievement was the Highway Beautification Act of 1965, or “Lady Bird’s Bill,” which not only promoted the planting of wildflowers and other fauna along the growing Interstate Highway System but also limited billboard advertisements and other roadside eyesores such as junkyards.

The bill was inspired by Johnson’s home state, where the Texas Highway Department started planting wildflower seeds in 1917, shortly after the agency was established. Johnson grew up in the East Texas town of Karnack, population 100, and these brilliant swathes of wildflowers along the shoulders of roads were a common sight for her. As a young girl, she spent much of her time outdoors, exploring the lakes, bayous, and dirt roads of her hometown. With her mother’s premature death when she was 5 years old, Johnson described nature as her daily companion. “The song of the wind in the upper branches of the pine trees is the most evocative symphony I’ve ever heard,” she recalled in 1988, at the age of 76. “I believe most of us cherish memories which have their roots in nature—a bond that forever ties us to the land.”

Johnson described nature as her daily companion. “The song of the wind in the upper branches of the pine trees is the most evocative symphony I’ve ever heard.”

In the ’70s, following her husband’s death, Johnson went to work on the beautification of the 10-mile hike-and-bike trail in downtown Austin. She also donated 60 acres and $125,000 in order to establish the National Wildflower Research Center, whose mission is to inspire the conservation of native plants. Founded in 1982 and renamed the Lady Bird Johnson Wildflower Center at the University of Texas at Austin in 1997, the center now consists of 284 acres in southwest Austin, with more than 970 species of Texas native plants on-site.

“Beautification was an easy door to open for people,” explains Lee Clippard, director of communications at the Wildflower Center. “People wanted to see beautiful flowers and beautiful landscapes, but she saw it as a way to heal the land. She knew it was a way to improve the lives of people. She always saw landscapes and people together.”

•

Though Johnson doesn’t mention it in the home movie at the LBJ library, the bluebonnet field that provided her “very native habitat” lies within the Blackland Prairie region of Texas. Historically, this has been one of the largest ecosystems in the U.S., but more recently, it has become an endangered habitat with less than 1 percent still remaining. Throughout much of the state, millions of acres of the original prairies—featuring deep, fertile soil and a mix of tall grasses and wildflowers—have fallen to construction and other human uses. Here, in Austin, it stretches throughout most of the eastern side of the city and was accidentally preserved in the Mueller Greenway because the soil was underneath the parking lot of the old airport. After Johnson’s death in 2007, biologist and ecology designer Mark Simmons of the Wildflower Center carried on her legacy. He worked with the Mueller development team, until his passing in 2015, to restore 30 acres of the greenway to its native grasses and plants, and transform it into one of the few wild lands in urban Central Texas.

“More or less, we have a functional prairie in the middle of Austin,” explains Michelle Bertelsen, ecologist and land steward with the Wildflower Center, who worked on the restoration with Simmons. By “functional,” Bertelsen is referring to how the prairie grasses grab carbon, pump it into the ground, and over time, how the carbon enriches the soil. One of the benefits of this organic process is that the ecosystem becomes more effective at absorbing and cleaning water. “We aren’t tree-huggers,” Bertelsen jokes, “but we are soil-huggers. When you find good soil, you throw your body on top of it and protect it because it’s really hard to build back. It takes a long time, and sometimes you can’t. This prairie was Mark’s vision—and it was audacious at the time. He saw that the soil was here and was pivotal to driving the landscape back toward the Blackland Prairie.”

The Lady Bird Johnson Wildflower Center in Austin features 970 species of native Texas plants in gardens and natural settings. Photo: Theresa DiMenno

Today, the Mueller Blackland Prairie features tall grasses, such as sideoats grama (our state grass), green sprangletop, big bluestem, switchgrass, and others. Since 2015, the Wildflower Center has not participated in the maintenance of the prairie. Due to this lack of expert oversight, several invasive species, such as King Ranch bluestem and Johnson grass, have taken over much of the southwest end of the prairie. Also, shrubby volunteer saplings can be found underneath many of the trees, and over time the prairie could become a woodland thicket, like west Austin. The ecologists at the Wildflower Center hope to rejoin forces with the development corporation and oversee prescribed burns. Nonetheless, the savanna, ponds, and prairies of the Mueller Greenway still reflect the original landscape of Central Texas.

About 150 new residents are added to the city’s metropolitan area daily, according to the Austin Chamber of Commerce, and many of these transplants don’t have a frame of reference for the natural Texas landscape. “It’s important that we don’t lose this biodiversity, so we don’t lose Austin,” says John Hart Asher, senior environmental designer for the Wildflower Center. Bertelsen adds: “Mrs. Johnson wanted places to reflect what they were, instead of having a homogenous landscape—a sense of place. Central Texas should look a certain way. She thought it should be recognizable. It should say, ‘I’m here.’”

Not surprisingly, Johnson also extolled the physiological benefits of nature long before landmark studies began to appear in academic journals. “My heart found its home long ago in the beauty, mystery, order, and disorder of the flowering earth,” she once said. “I wanted future generations to be able to savor what I had all my life.” She intuited that spending time in nature decreases stress levels, improves memory and focus, eliminates fatigue, fends off anxiety and depression, and engenders empathy toward others. She considered being among native plants in an undisturbed habitat akin to a spiritual communion. “She saw the regenerative power that green space and landscapes could have on the human condition,” Clippard adds. “It can lift them out of depression or whatever else they are facing.”

•

My runs, begun as a teen with inspiration from my mom, are now largely inspired by the ideas Johnson promoted long before others did. Each morning that I run along the familiar trails of the Mueller Greenway—from the 23-foot spider sculpture to the edge of I-35 and back again—my overall sense of well-being and perspective vastly improve. The expansive prairie, the fresh air, the birds, and the changing light seem to set the world on its right axis and align things in such a way that all feels OK.

Admittedly, during the past six years, there were many mornings where things didn’t feel OK. In October 2012, my mom suffered a nervous breakdown that began an odyssey of psychiatric wards, electroshock treatments, assisted-living facilities, and social workers. With the exception of an eight-month period where my mom returned to some semblance of her former self, her precarious mental state created a constant crisis of figuring out how to best take care of my mom and her needs. For me, coping with her mental illness—and all that went with it—often felt like being battered in the undertow of a powerful current that came and went. At first, the electroshock treatments worked, but then they didn’t. For the first hour after a treatment, she would sound like her old self—a laugh, a joke, a subtle strum of happiness in her voice—but then this part of herself would disappear, seemingly canceled out by her endless loop of acute anxiety and depression.

•

Sometimes, during the winter months, I didn’t want to go running. I sat in my Honda Fit with the heat vents going, sipping my lukewarm coffee and contemplating the lace of frost on the prairie. It felt like a dive off the starting block into a frigid pool. But once I began, I always felt better. The whistle through the stands of grass, a pair of mallards gliding across the pond’s surface, the open face of a hardy Maximilian sunflower. It was another day. The landscape and the sky and the wildlife rearranged things for me—the molecular structure of my grief and happiness, and everything in between—and my day took on a more fluid, buoyant quality. Instead of being weighed down by the demands and challenges of my mom’s ongoing care, I felt grateful for another morning and the possibilities that might lie ahead.

•

Last fall, I was on the phone with a social worker. By this time my mom was a resident in the temporary wing of a nursing home in southeast Detroit. In order to transfer her to the long-term floor, the social worker needed to perform an hour-long interview about my mom’s history—the depression, the suicide attempt when I was 5, the untreated alcoholism, the post-traumatic stress. Like other individuals with mental illness, my mom also accomplished a lot during her lifetime: She returned to school, earned a masters of education, and became the president of her professional organization. She loved gardening and classical music. Her mental illness won out, though, rupturing many relationships along the way.

Johnson considered being among native plants in an undisturbed habitat akin to a spiritual communion.

By the conclusion of the interview, the social worker asked, “How did your mom take care of four children?” I didn’t really have an answer for her. Growing up with an unstable mother was hard for my older siblings and me. We each found different ways of coping. For me, I played sports. I ran. Later, I discovered my passions of reading and writing, and then teaching creative writing. I managed to marry a kindhearted man. And, down here in Texas, I have the birds, the wildflowers, the open sky. Like Johnson, I have found refuge in my daily encounters with nature. There is a seamless interplay between the exterior and interior landscapes—how they shape and push against each other. Throughout much of my life, nature has offered up solace and comfort when my mom hasn’t been able to. The brightening ambers, oranges, and blues of a sunrise. The annual revolution of wildflowers emerging along the sloping shoulders of Texas’ highways and then dying away. There is an ease, a relief, and a reminder: Nature—and life—changes, and so do we.

I imagine this might have been true for Johnson. She sought out the unconditional beauty and serenity of nature when she couldn’t find this kind of comfort elsewhere, particularly as a young child after her mother’s death. It was in this loss that she discovered her passion for the outdoors, and later her strength and voice, and became one of the environment’s most ardent advocates.

•

Sometimes I try to remember my mom before her illness took over. Our last walk together was along the trails of Cranbrook, where I used to run as a teenager in Michigan. It was early June 2012. A family of swans perforated the nearby lake, and coral-colored coneflowers, black-eyed Susans, and clusters of white hydrangeas were in bloom. My mom talked about her worries regarding the family as we circled the lake. Despite this, I found a sort of unspoken consolation in the familiar landscape, the matching rhythm of our footfalls, the profusion of blooming flowers. We were spending time together in the best way we knew how.

•

Each morning that I take to the trail, I begin again. I witness the golden orb of the sun making its way over the eastern horizon. The tips of the prairie grass gently undulate. I say good morning to my fellow trail runners and dog walkers. I feel the cool air travel into my lungs. I continue down the path, one foot in front of the other. A large flock of doves takes flight and gathers into an oval formation before shape-shifting into a loose arrow and breaking apart again. I think about what Johnson said about the pleasure of being in her “very native habitat.” I remember her vision for bringing beautiful landscapes and people together, the healing power of the land, the regenerative effect of green spaces on the human condition.

This greenway—and all of its native occupants—has become my adopted habitat. Each morning, it reminds me who I am. And that I’m here.

S. Kirk Walsh has written for The New York Times Book Review, Longreads, and Virginia Quarterly Review, among other publications. She collaborated in the writing of One More Warbler (University of Texas Press, 2017) and is currently at work on a novel. Follow her morning run photos on Instagram @skirkwalsh