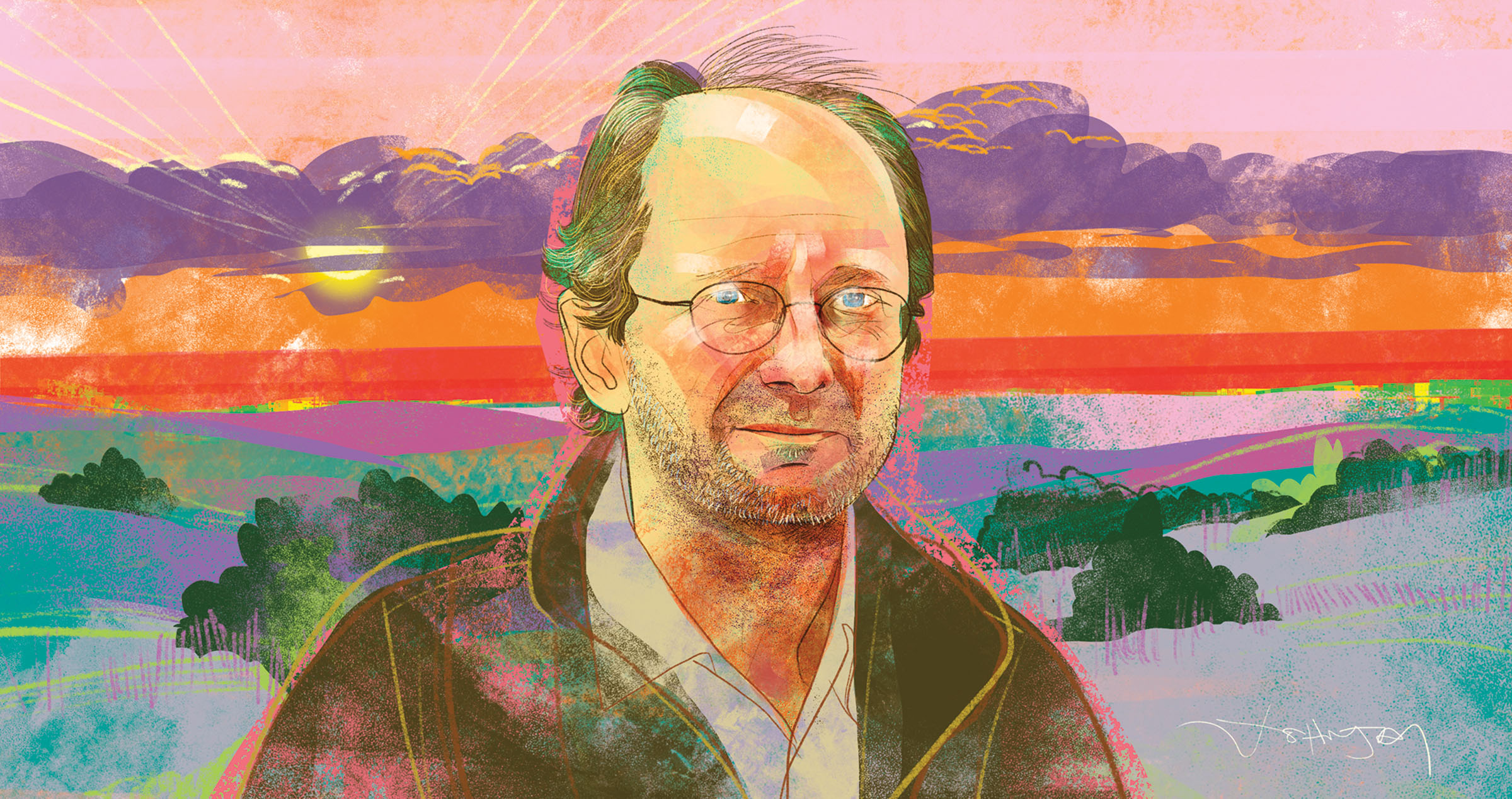

Illustration by John Jay Cabuay

The thing about Texas is she has this gravitational pull on her native children. We all return, even if not always physically. Writer Rick Bass grew up in Houston, where he tromped through hardwood forests around Buffalo Bayou and made trips to the Hill Country to hunt deer. The son of a geologist, Bass had oil in his blood, along with a craving for wild and untouched places.

Bass followed in his father’s footsteps and studied petroleum geology. He then went into the business himself, sniffing out oil deposits, first in Mississippi, then Montana. But a curious thing happened in the process: The hunt for oil started getting in the way of his passion for writing. So, one of them had to go.

Now a nationally known environmental advocate and award-winning author of dozens of books of essays, fiction, and nonfiction—much of it set in a West at once boundless and under siege—Bass returns to the motherland in his latest collection, Fortunate Son, released this spring.

The book’s 16 essays, both old and new, form a kind of Lone Star collage. Bass studies with equal interest the hunting dogs and the people who send them to a rigorous training camp in the Lost Pines near Bastrop. He gets a little lost in the wilderness deep within Sam Houston National Forest. He dreams with the could-have-beens on a semipro football squad in Brenham. And while floating across a marsh just down the coast from Galveston, he marvels at ibises and the supertankers that share the horizon with them.

Bass’ writings are shot through with warmth and worry. While he has lived in Montana’s remote Yaak Valley since 1987, Texas and what it means to be an ex-pat Texan still occupy Bass’ mind.

TH: When did you begin thinking about compiling a collection of essays about Texas in all its beauty and contradiction?

RB: I can’t help but think that at some subconscious level the strife and aggravations and polarizations of the last four-plus years—the rising intensity of civic engagement and dialogue—made me go back and look at how I’d written about the place I’m from. It’s an interesting filter, the tenor of the times, to look back at a place that’s been under a lot of pressure, as have all places.

TH: How’d you come to the title Fortunate Son? After reading the book, I’m sensing shades of Creedence Clearwater Revival.

RB: The phrase certainly harks immediately to CCR. And we are at war. Not just Texans and Montanans, but the world. So there’s a bit of irony. We’re still in a bit of denial about climate change, or too many of us are. And just straight up—neither jeremiad nor confessional—I am fortunate to have grown up in Texas and have my parents teach me what they taught me, including my father, a geologist.

TH: What did you discover looking back at your old writing through the lens of these times?

RB: I discovered a lot of innocence. I did not go into the subjects or stories with any concept of historical passage of time or cultural preservation. That’s just what art does: It increases value over time. That’s one of the great things about it. If it’s good on its own at the moment, it’s going to be better over time. But I was struck by the innocence of what writer Wendell Barry calls “the absence of foreknowledge.”

TH: What else did you take away about yourself, looking at these stories in their totality?

RB: I realized something I already knew, but it heightened the clarity of focus:

I like to move in spaces between things. Between cities, between crowds. Like a wide receiver in a zone defense, I like to sit down in the middle and be below the safeties and behind the linebackers. I don’t like bumping into people. Most of the essays in this collection don’t really address my disposition or predisposition for, if not solitude, then space. Looking at one after the other, it’s striking to me how rarely I’m in a crowd. When I think of Texas I think, “Man, there’s a lot of people and cars on the road.” That’s no judgment, it’s just how it is. There are a lot of us. But in those essays that’s not what’s presented, and it’s not what I pursued, even then.

TH: There’s something about being a native Texan that isn’t like other places. You call it our “parochialism.” We can criticize her but outsiders can’t. Why?

RB: It sounds like love, doesn’t it? There’s no explaining it. Do we contradict ourselves? Yeah, we do. My answer for everything is either geology or landscape. And Texas certainly has such sheer magnitude of size and this broad representation of landscapes that there’s a lot to love. It’s going to be a more full and complicated relationship. But of course being large [makes the state] vulnerable to a lot of imperfections.

TH: As a naturalist, how do you write about a state that so often seems at war with nature?

RB: I think the answer to any question about writing, to be neither snide nor facile, is specificity. Good writing is specific. So if you’re going to write about the natural world, attentiveness to detail will take you far. That’s not all there is to it, of course. I think with such an increasing estrangement from nature, certainly from wild nature, finger wagging is not going to engage the reader. You have to tell a story with a beginning, middle, and end, and with something at stake that the reader supports, is engaged by, and cares about. That’s the heart of storytelling.

TH: What do you want your grandchildren to know about Texas?

RB: It sounds kind of passive, but I just hope there’s something about the state for them to find and love. The stories I want them to remember are mostly family-based, rather than place-based. With the exception of the Hill Country. That’s such a phenomenal place in nature, anywhere around the world. The oldest granite. The oldest sandstone. It’s a singular geological place.

TH: My favorite story was about you turkey hunting with musician James McMurtry. I sensed a kinship there—two men with a deep connection to Texas, but who might not identify as Texan.

RB: I can’t speak for James. Nobody should speak for James. But I would not disagree with your perspective. I asked him as much: “How do you feel about being a Texan?” And he said, “I’m from Virginia.” It’s him being tongue-in-cheek because you are from where your art is from, and his art is from Texas. Not all of it, but the heart of it is.

TH: What about you?

RB: A big chunk of my art’s from Texas. I share that with him. Not all of it. A lot is from Mississippi, a lot from Montana.

TH: You flew many miles with aerial photographer Jay Sauceda, including when he took the Panhandle shot on the cover of the book. Did seeing the state at such an altitude—and that much of it—change the way you look at Texas?

RB: It was intense and wonderful. The classic contrast between space and time. It made the physicality of the state seem disparate, which I always knew, just through color. Green to red. Green to orange. Blue to white. It also made it seem small. Even at 100 knots in a Cessna, your perceptions are so different. That juxtaposed with history and time. Particularly so on the Rio Grande, the so-called border. But it’s not a border to the wind. It’s not a border to geology. It’s not a border to animals. It’s just a river. It’s an interesting and, I think, productive way to think about one’s home.

Rick Bass will discuss his book Fortunate Son in an online event with San Antonio’s Twig Book Shop at 7 p.m. July 8. The free event requires advance registration at thetwig.com.