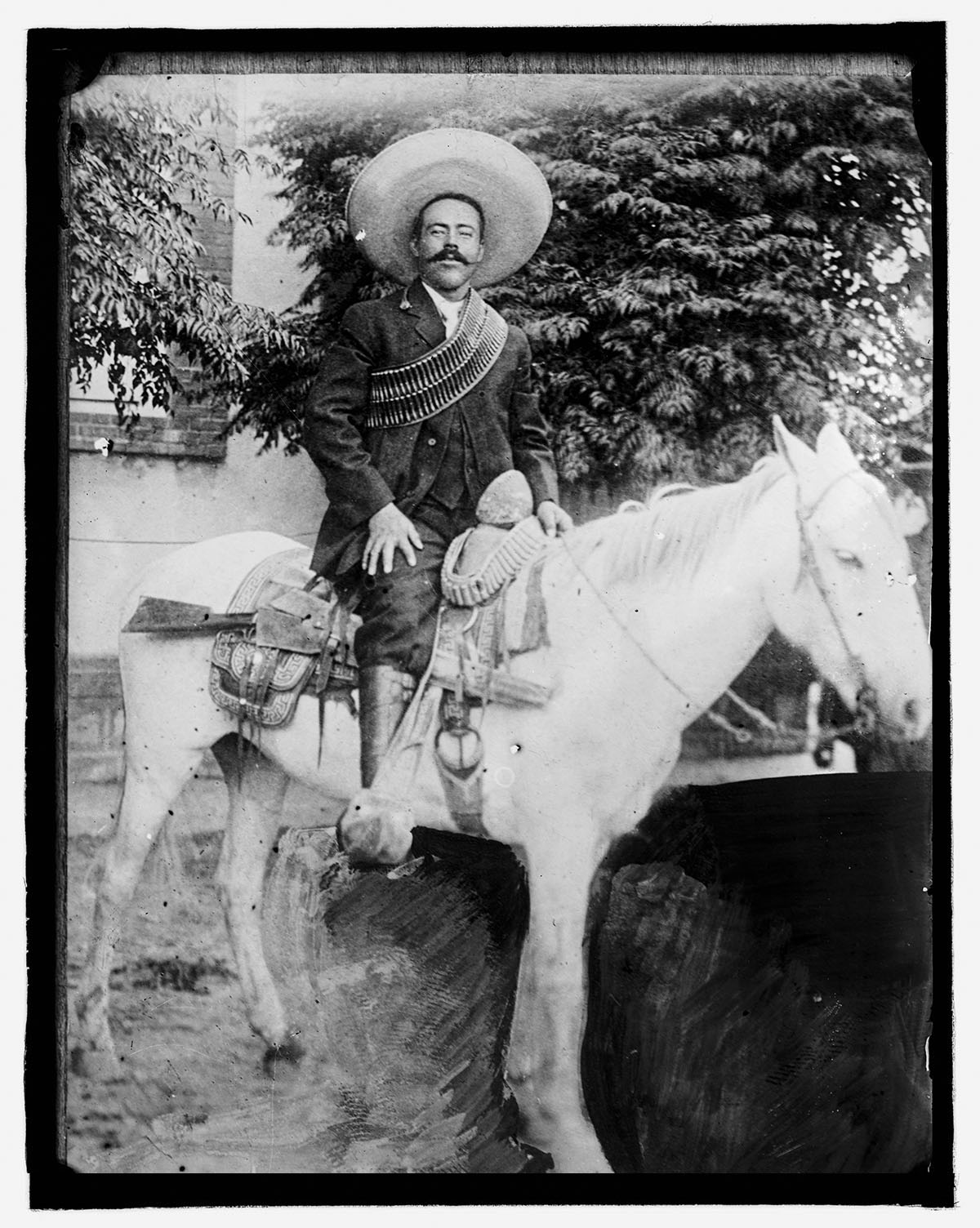

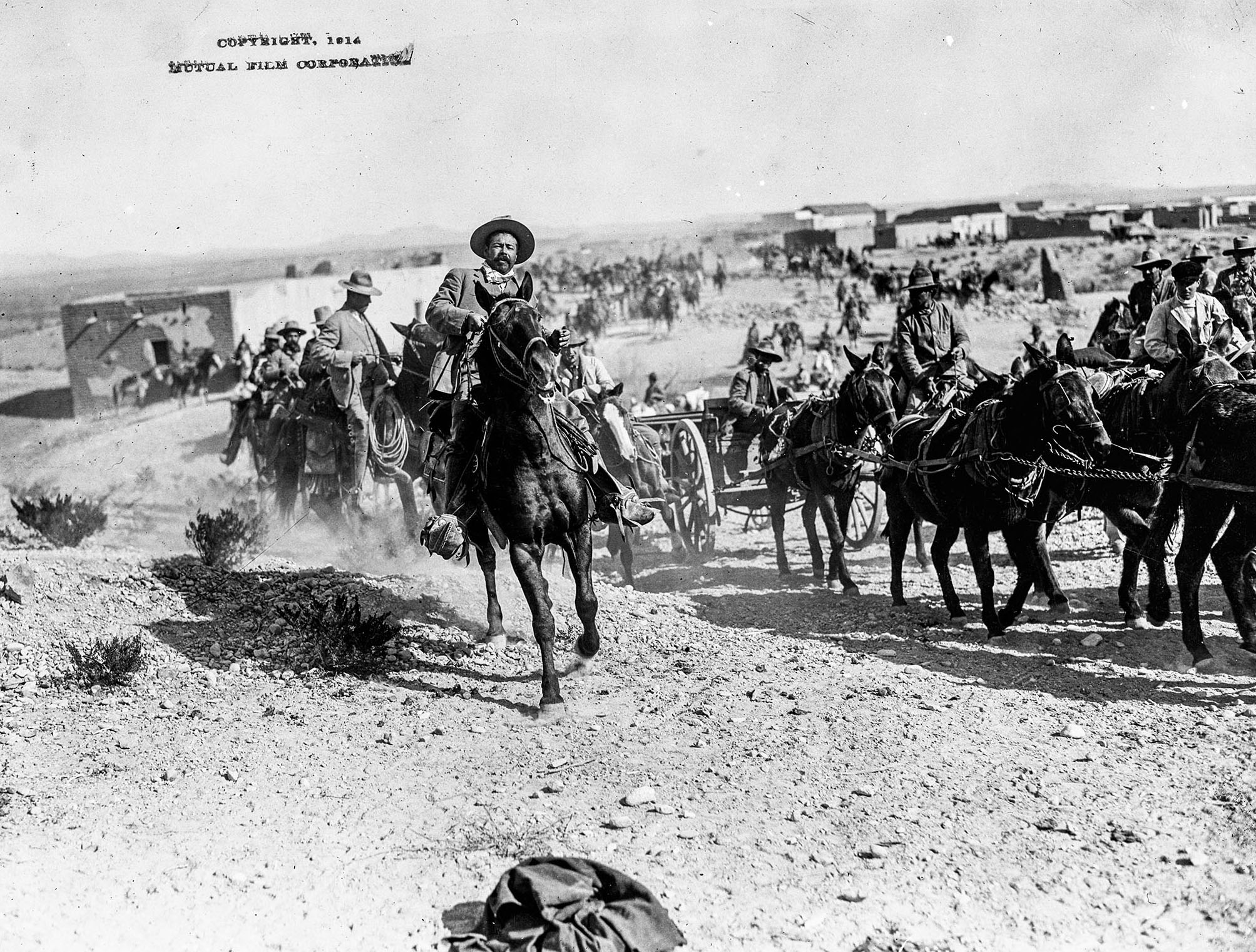

Pancho Villa circa the 1910s. Photo courtesy Library of Congress

The Centaur of the North

Revisiting the El Paso haunts of Pancho Villa, the controversial and charismatic Mexican folk hero

By W.K. Stratton

One hundred years ago, rifle fire shattered the morning calm

in Hidalgo del Parral, Chihuahua, Mexico, roughly 400 miles due south of El Paso. Assassins aimed their guns at the driver of a black Dodge Brothers touring car. He died instantly that July day as nine bullets tore through his body. Once the shooting ended, stunned townspeople flooded the intersection where the car had been ambushed. The Dodge’s 45-year-old driver was none other than Pancho Villa, the most famous—or infamous, depending on who you ask—leader to emerge from the Mexican Revolution.

Approximately 2.5 million Mexicans out of a population of roughly 15 million died during the war, which began in earnest with the ouster of dictator Porfirio Díaz in 1911. Díaz ruled the country with an iron fist for three decades. The upper tier of Mexican society lived in luxury, but most of the country was mired in dire poverty. Díaz’s successor, Francisco Madero, died in a bloody coup led by Victoriano Huerta in 1913. The revolution then devolved into a decade-long civil war involving several different factions, including one led by Villa that came to be known as the “Villistas.” Called the “Centaur of the North” for his skilled attacks while on horseback, Villa was a charismatic yet controversial figure who had no small number of enemies. Still, it was surprising that he’d be gunned down in Parral, a relatively quiet, small city where friends far outnumbered foes, since Villa had laid down his arms three years earlier.

Villa’s violent death, believed to have been orchestrated by Mexican President Álvaro Obregón, made news around the globe. It especially resonated in Texas, where Villa had strong support among Tejanos yet was held in disdain by many Anglos. “Mexicans and Mexican Americans don’t have any other iconic figure that comes anywhere close to Pancho Villa because he was so historically important in Mexico and North America,” says Andrés Tijerina, a Tejano historian who has written extensively about South Texas. “And because he tweaked the nose of the gringos like no one had ever done before.”

In alliance with another important leader in the revolution, Emiliano Zapata, Villa essentially conquered the nation in 1914. The duo posed on the gilded throne of Mexico’s president to celebrate. Villa’s fabled División del Norte, which numbered as many as 50,000 soldiers at its peak, won battle after battle. Villa knew how to manipulate the media and was the subject of countless newspaper stories worldwide. In 1914, he even acted in a major American motion picture about himself, The Life of General Villa.

Villa’s detractors condemn him as a womanizing, violent bandit who ordered prisoners to be executed and who murdered people himself. But he was also a charismatic political leader and a fearless, innovative military commander who was among the first to employ aircraft, machine guns, and other modern weaponry in combat. At the same time, he embodied traditional Mexican values and cared deeply about his countrymen, especially the poor. “Never had I doubted the justice of our cause,” he once said, “through 22 years of fighting for what I believe to be the cause of liberty, of human liberty and justice.”

Villa had close ties with Americans at times, particularly in El Paso, which he considered home at different points of his life. In anticipation of the 100th anniversary of the revolutionary’s death, I set out last spring to explore the Texas connections of this Mexican icon.

Doña Maria Luz Corral de Villa

Married to Pancho Villa in May 1911, “Luz” was known as his “main” wife.

Abraham González

A key figure in the insurrection against Mexican dictator Porfirio Díaz, González recruited Villa to the cause

Álvaro Obregón

The President of Mexico from 1920-1924 and the likely orchestrator of Villa’s death.

Friends and Foes

Key figures in Pancho Villa’s life

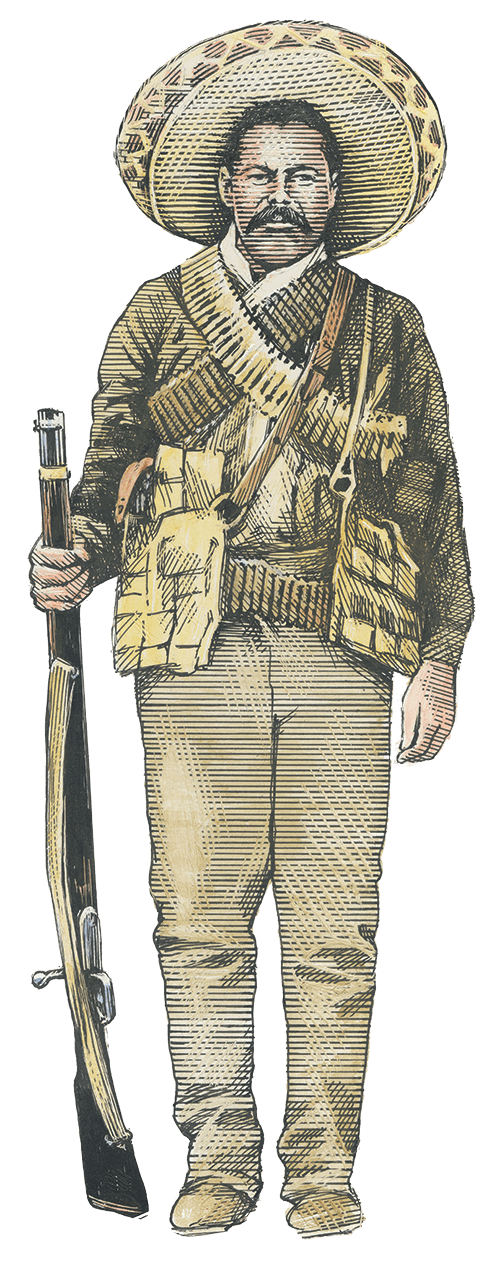

Pancho Villa

José Doroteo Arango Arámbula’s nicknames included the Centaur of the North, the Mexican Napoleon, and the Mexican Robin Hood.

Illustrations by Kent Barton

Emiliano Zapata

Villa’s ally, Zapata was a leading figure in the Mexican Revolution and a champion of agrarianism.

Francisco Madero

Another opponent of Díaz, Madero served as President of Mexico from 1911-1913, when he was assassinated.

Victoriano Huerta

Villa’s bitter enemy. He served under President Madero before having Madero killed. Huerta was President of Mexico from 1913-1914

No American city played a more important role in the revolution than El Paso, the primary port of entry for arms, ammunition, and other goods used in battle. It was where the world’s reporters gathered to cover the revolution and agents from Germany and other nations carried out espionage missions. Most of the major leaders in the revolution crossed into the city at one point or another, though none had a more significant presence than Villa. But it would have been impossible to predict his future stature as a political and military leader when he first arrived in El Paso around 1909 as a hard-luck peon turned outlaw.

In 1878, Villa was born on the Rancho de la Coyotada—565 miles south of El Paso—part of one of the largest haciendas in the state of Durango and owned by the López Negrete family. His parents of record, Agustín Arango and Micaela Arámbula, were sharecroppers on the hacienda, but there is dispute about who his real father was. In La Familia Secreta de Pancho Villa, author Rubén Osorio asserts Villa’s real father was a wealthy hacendado, Luis Fermán Gurrola, who at some point impregnated Arámbula—it’s not clear whether it was consensual. Regardless of who his father was, Villa was baptized José Doroteo Arango Arámbula and raised as a peon on the Rancho de la Coyotada.

Peons were not slaves, but they weren’t exactly free either. Mexican class structure dictated that young Doroteo Arango live out his life in grinding rural poverty under a brutal Durango sun. But he became an outlaw instead and eventually changed his name to Francisco “Pancho” Villa. As a teenager, he joined a gang in Durango’s hill country, where he was a thief and armed robber. Villa soon expanded his criminal activities into the larger, more populous state of Chihuahua, and he didn’t hesitate to kill when he thought it was warranted. Too often overlooked are the organizational and leadership skills that he developed in his 20s as the leader in an outlaw network in the Chihuahuan underworld. Also overlooked are the acts of compassion he showed to Mexico’s poor. “That man is only a bandit, an ignorant peon,” his enemy Huerta, who was President of Mexico from 1913-1914, once said. “Es un inculto [illiterate]. Villa can hardly spell his name.”

In America, much of his real-life acumen is lost in hackneyed portrayals of a “border bandido,” as in MGM’s 1934 film Viva Villa! It starred Wallace Beery, a white man from Missouri, as a cartoonish Villa, delivering clichéd line after clichéd line. The picture was a hit in the U.S. and cemented the template for how Villa would be portrayed in the American media for decades to come. In Mexico, however, the press condemned Viva Villa! as derogatory and urged theater boycotts. “I always get offended by how people write about Villa, trivializing him as a border bandit with a big mustache—the old racist tropes,” says David Dorado Romo, author of Ringside Seat to a Revolution.

It’s unclear what first brought Villa north to El Paso sometime around 1909. At least one person who befriended him said Villa worked at the infamous Guggenheim-owned ASARCO smelter, which belched toxic pollutants into El Paso skies for generations. If Villa indeed worked there, it was only for a short time. At some point, M.L. Burkhead, a pioneering Far West Texas car dealer, met Villa at the stately three-story El Paso County courthouse built in 1886. (It was demolished in 1917.) Burkhead later told an oral historian that Villa was “stocky and though he wore the typical clothes of the poorer class, he had a proud look about him. He was sizing me up as I was him.” Burkhead learned that Villa was surviving on less than a dime a day.

The car dealer engaged enthusiastically in cockfighting, popular on both sides of the Rio Grande at the time, and he discovered Villa had expertise in the blood sport. He hired the 30-something to tend to the roosters at his pens in the 1200 block of Second Street and to participate in the cockfights in both El Paso and across the river in Ciudad Juárez. Burkhead paid the future Centaur of the North $3 a week.

Villa’s stay in El Paso didn’t last long. By early 1910, he was living in Chihuahua, where he met Abraham González, a primary figure in the developing insurrection against Porfirio Díaz. González recruited Villa to the cause, which was being mapped out in Texas. The rich young landowner Madero emerged as the leader of a complex revolutionary effort to remove Díaz as dictator. As a political exile from Mexico, Madero made his way to San Antonio. In rooms at the Hutchins House hotel, at 205 Garden St. (later St. Mary’s St.), Madero planned the opening salvos of the Mexican Revolution.

After studying his options, Madero selected El Paso as the starting point for the military operation against Díaz. He crossed the Rio Grande just downstream from the city with a group of armed rebels on Valentine’s Day 1911. Villa joined Madero’s forces in Chihuahua and was soon promoted to colonel in a rapidly growing revolutionary army. Friedrich Katz, author of the definitive The Life and Times of Pancho Villa, writes, “It was always Villa who took the initiative. He did not shy away from tackling steep odds, as when he attacked a superior federal force with only a few men under his command at the battle of Tecolote.” Those traits appealed to Madero, as well as Villa’s ability to recruit fighters for the cause. Díaz was overthrown three-and-a-half months later.

Between 1911 and the end of 1915, Villa was frequently in El Paso, where he procured weapons and other war supplies from merchants capitalizing on all factions south of the river. Merchants like German immigrant Adolph Krakauer, who owned a large wholesale hardware company in El Paso, profited from selling goods to both sides. “He sold barbed wire to Huerta and wire cutters to the Villistas,” Romo says. “There were many, many arms merchants who made a killing. In 1913 alone, Shelton-Payne Arms Company made $1.3 million from sales of ammunition and weapons—that’s worth more than $40 million today.” Villa was skilled in his El Paso dealings. “There was a lot of complexity and modernity to the man and to the movement,” Romo adds. “You had all sorts of national and global things going on behind the scenes in the revolution that are quite modern in nature.”

With Romo, I tour locations in the historic Chihuahuita and El Segundo barrios on El Paso’s southside. At one point he stops and points out a Burger King a short walking distance from the border at the intersection of Paisano and El Paso streets. “That’s where the Roma Hotel stood,” Romo says. “It was a center of activity for the Villistas in El Paso during the Mexican Revolution.”

Villa himself once called the hotel home. During the bleak year of 1913, Huerta held Mexico in a stranglehold after he arranged the assassination of Madero as part of a coup. Then he installed himself as president. Villa, a Madero loyalist, wound up in prison but escaped. He ended up in self-imposed exile in El Paso at the Roma Hotel with his “main” wife, Luz Corral. She told the El Paso Times in 1953 that Villa had at least 20 children by as many as seven wives. He did nothing to hide his polygamy.

Luz and Villa were often seen strolling the streets while Villa cradled pigeons he lifted from the sidewalk. But his focus was on returning to the revolution. He was a regular at the hotel bar, the Emporium, though he never drank liquor; a man with an insatiable sweet tooth, Villa gulped strawberry soda like a child. His time at the Emporium was anything but social. He met with operatives who updated him on political and military events in Mexico and discussed economic matters with El Paso business leaders. Eventually the Villas left the Roma and moved to a house in El Paso.

In May 1911, Villa was photographed eating ice cream at the Elite Confectionary at the corner of Mesa and Texas streets. A couple of blocks away, he opened the Consulado de México in the First National Bank building at the corner of Oregon and San Antonio streets. Villa met with his secret agents there. He also had offices in the Mills and Toltec buildings. An innovator in combat, his troops were among the first in the world to use motorcycles, which Villa acquired from a dealer in El Paso. He also maintained his friendship with his cockfighting associate, Burkhead, and purchased vehicles from his car dealership.

Villa bought a house for Luz at 608 Oregon St., and he bought another for his mistress Soledad Seañez just two blocks away. At 329 Leon Street, there is a dwelling often referred to as the Pancho Villa “stash house,” although Romo is quick to point out that Pancho never lived there. It belonged to his brother Hipólito’s father-in-law. The U.S. Treasury Department raided the house in 1915 and discovered $500,000 in cash plus a fortune in jewels. Some of the money may have belonged to Pancho, Romo says, but Hipólito had “extravagant tastes and figured frequently in U.S. government reports of graft.”

The meeting lasted several hours, and most of the items of discussion were never disclosed publicly. However, the El Paso Times reported the next day that Villa had agreed to restore seized American property in Chihuahua and to back off from “war loan” assessments imposed on U.S. companies operating in Mexico.

After the meeting, Villa and Scott crossed the river to watch horse races in Juárez. Their meeting marked the peak of Villa’s popularity in the U.S. “Scott developed strong feelings of sympathy and admiration for Villa, which never wavered,” Katz writes. But President Woodrow Wilson and his administration had other ideas, throwing their support behind Villa rival Venustiano Carranza.

Feeling betrayed, Villa turned his ire on the U.S., culminating in his 1916 raid on Columbus, New Mexico, on the Mexican border 80 miles west of El Paso. Eight American civilians and seven U.S. soldiers died as the Villistas attacked the tiny town and the adjacent Army post. Villa’s troops burned Columbus and absconded with horses and mules, ammunition, machine guns, and store merchandise. That Villa had the moxie to attack the U.S. only added to his legend in Mexico, but it came at a cost. President Wilson ordered Gen. John J. Pershing, commanding general of Fort Bliss in El Paso, to lead an expeditionary force into Mexico to capture Villa. Pershing failed to apprehend Villa, but Villa’s role in the revolution went into decline. Without a leader, his forces essentially disbanded. No credible evidence exists that Villa was in Texas after 1915.

My friend Sergio Troncoso’s grandmother, Doña Dolores Rivero, grew up in dire poverty on a ranch in El Charco in the state of Chihuahua. “She was beneath working class,” says Troncoso, a successful author who was born in El Paso. “She washed clothes for teachers.” Rivero was also a confirmed Villista. Troncoso remembers visiting his grandparents at their apartment in El Segundo Barrio and hearing them discuss Villa. “Usually it would start with music, a corrido about Villa,” Troncoso says. His abuelita would light up.

Troncoso and I talk about the lasting appeal of Villa. Certainly, there is the “bad boy” aspect: the outlaw, the ladies’ man. He was also a proud Mexican who refused to defer to white people. But most importantly, he legitimately cared for the downtrodden. He had been one of them. “He spoke up for the very poor, for los peones,” Troncoso says.

For decades after his assassination, Villa was officially persona non grata in Mexico as former enemies, including Obregón and Plutarco Elías Calles, assumed the nation’s presidency. But by the mid-1970s, political sentiments in the nation had changed, and Mexico recognized Villa as a hero of the revolution.

In 1981, nearly 60 years after his death, Villa made a triumphant return to El Paso, this time in the form of a 14-foot, five-ton statue. It was a gift from then Mexican President José López Portillo to the people of Arizona. The statue crossed through El Paso on its way from Mexico City to Interstate 10, the highway that would take it to Tucson. Hundreds of people from Juárez and El Paso turned out to see the statue cross the bridge from Mexico to the U.S. There were handshakes, poems, songs, and occasional gritos. One high school student proclaimed him “our general.” Four decades later, for many Texans, he remains so.

An 8-foot-tall statue of Villa shaking hands with Pershing currently stands in the plaza outside the Hotel Paso del Norte in downtown El Paso. The Villa in the statue is no sombrero-wearing bandido cliché. Instead, he is shown as the military man and leader he was.