A Quiet Place

Forty years ago, classic film Tender Mercies

put Waxahachie on the movie-making map

By Wes Ferguson

Photos courtesy Alamy

FM 878 is a lonely road,

but it’s not a long one. It meanders for a mere 11 miles through the open prairie between Waxahachie and Palmer. There are plenty of crop fields and pastures to look at. A few low creeks trickle past. The road gets hardly any traffic—and that’s why Marvin Borders was so flummoxed.

Borders, a gentleman farmer and lifelong Waxahachie resident, was driving through a particularly empty stretch of FM 878 more than four decades ago when he noticed some people installing gas pumps in front of a small, abandoned farmhouse. A couple of motel cabins were going up on either side of the house. The unassuming complex sat at the edge of a plowed field of dirt sweeping off to the north as far as the eye could see. Situated 30 miles south of Dallas but a world away from the hustle and bustle of the Metroplex, it was hard to imagine a more ill-advised spot for that sort of business venture. The farmer needed to warn these strangers before it was too late.

“My grandpa was kind of a Nosy Nelly, and he would talk to anybody,” recalls Borders’ granddaughter, Amy Borders, a Waxahachie native who was a little girl at the time. “He pulled up and told them that was not a good place to build a gas station.”

“Oh,” a member of the crew replied. “We’re building a movie set.”

The emptiness, in this instance, was perfect. Hollywood had discovered the Texas prairie, where the flatness and vastness, paired with epic skies, was stark enough to imbue any film with a sense of isolation. The little farmhouse next to the crop field became the desolate setting for Tender Mercies, an understated film that is widely considered one of the finest movies to ever come out of Texas. “Rarely does a movie elaborate less and explain more,” film critic Roger Ebert wrote admiringly in 2009 when he included Tender Mercies in his book, The Great Movies IV.

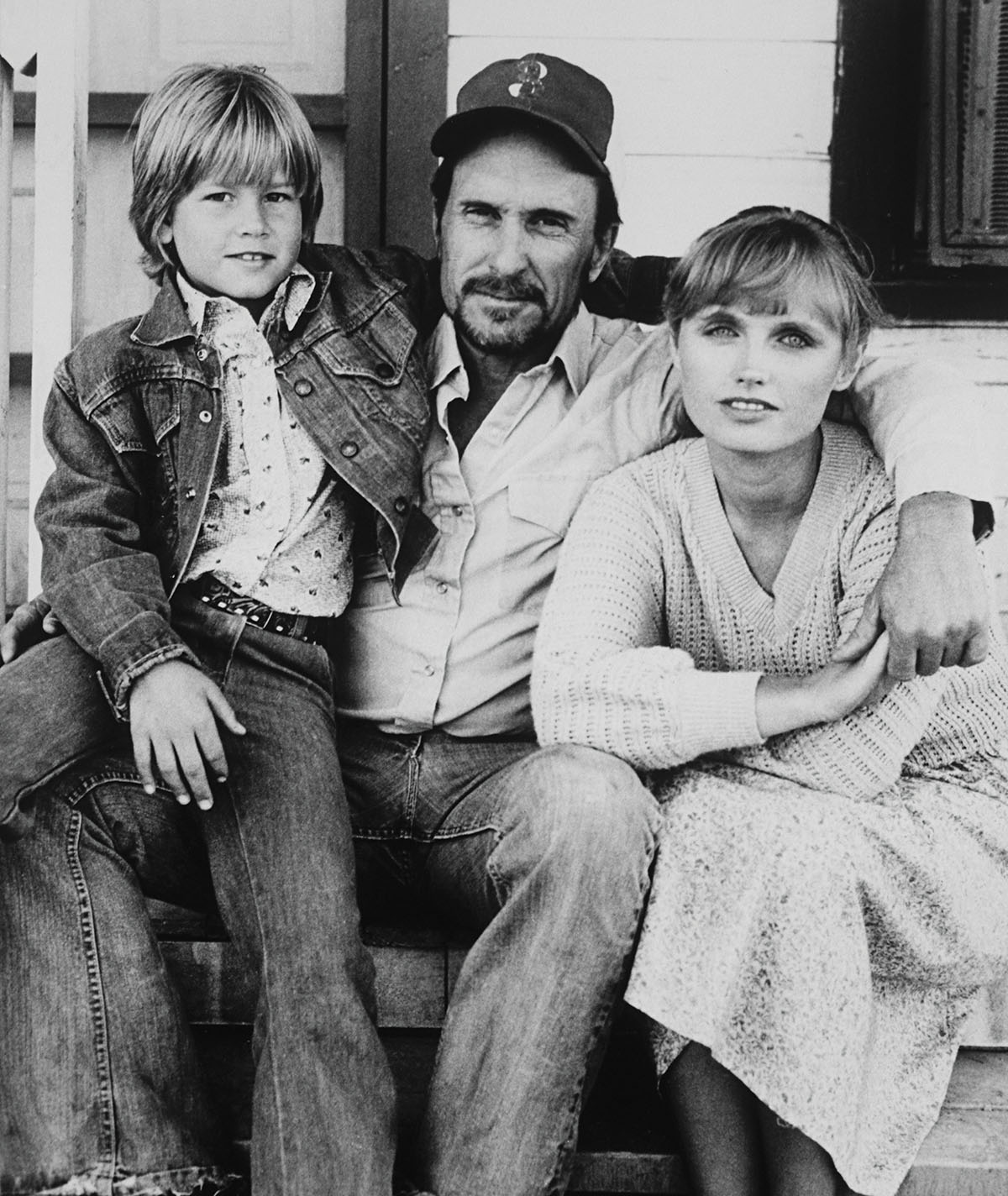

The film is quietly marking its 40th anniversary this year. As of this writing, there are no scheduled commemorations or special screenings in the U.S., a fittingly no-fuss milestone for a 1983 box office flop that never found a wide audience—but did go on to garner critical acclaim, earn a raft of Academy Award nominations, and win Robert Duvall his only Oscar for his unforgettable turn as washed-up country singer Mac Sledge.

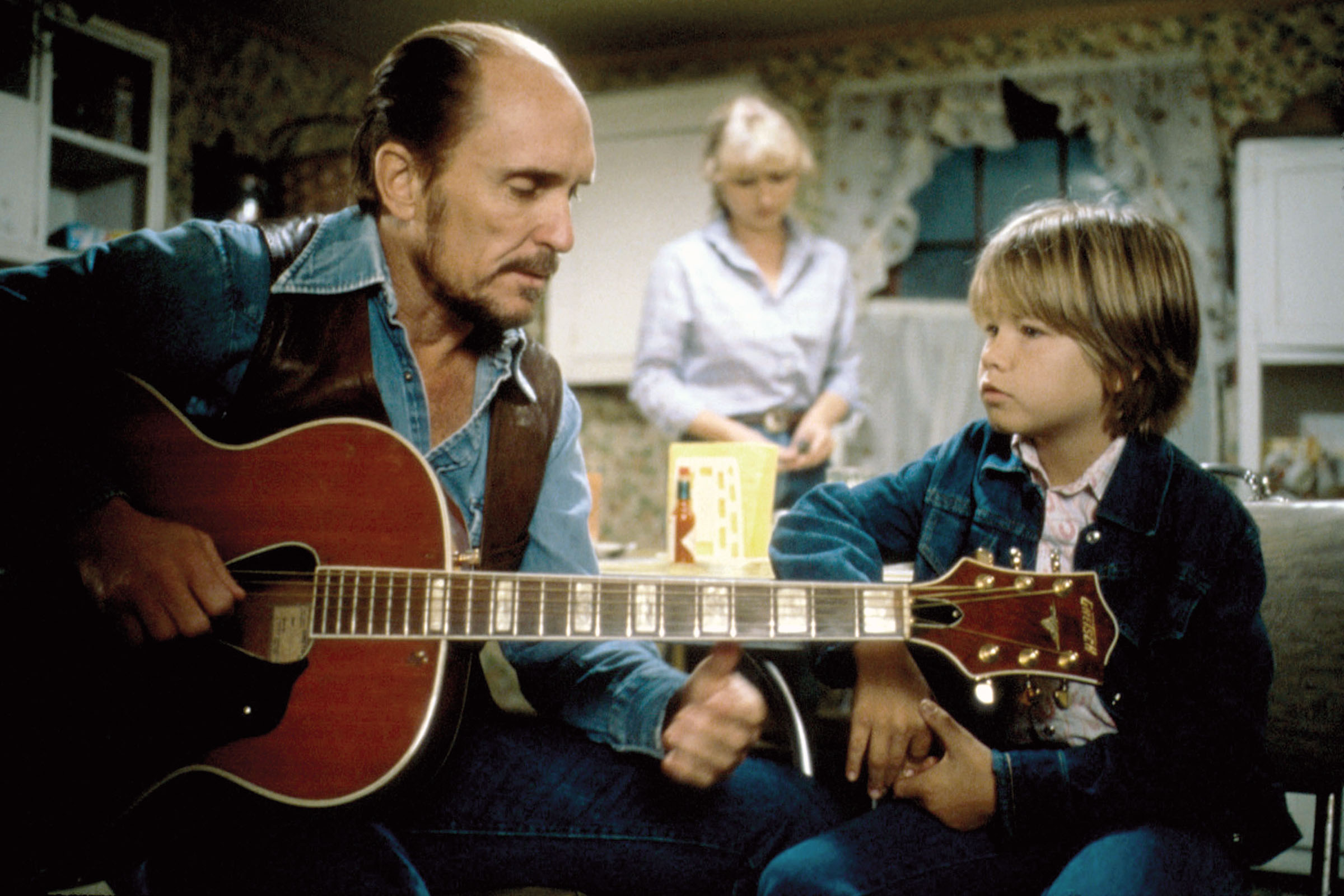

When Mac can’t pay the bill for his room at the Mariposa Motel, the motel operator, a young war widow named Rosa Lee, allows him to stay on and work. While weeding the garden just a few scenes later, Mac puts forth a wedding proposal that is bound to be one of the least romantic in cinema history. “Would you think about marrying me?” he asks. Rosa Lee, who needs a father for her son, Sonny, agrees.

Some news reports have claimed that Mac’s character was loosely based on country legend George Jones, the southeast Texas native whose alcohol and drug addictions were frequent tabloid fodder. But acclaimed screenwriter Horton Foote told an interviewer in 1999 that he found inspiration for Mac elsewhere: “George Jones, I understand, thinks I’d written about him. But I really was thinking about actors I’d known [who] had enormous talent, that alcohol had just licked them.”

Either way, Duvall was on board. A talented guitar player with a soulful voice, he’d always wanted to play a country singer, and he was eager to reconnect with Foote, one of the foremost dramatists of the 20th century. Foote had grown up in the sleepy cotton farming town of Wharton, about an hour southwest of Houston. Many of his works are set in a fictionalized version of his hometown, and he’d won an Oscar for his adaptation of 1962’s To Kill a Mockingbird, Duvall’s first film appearance.

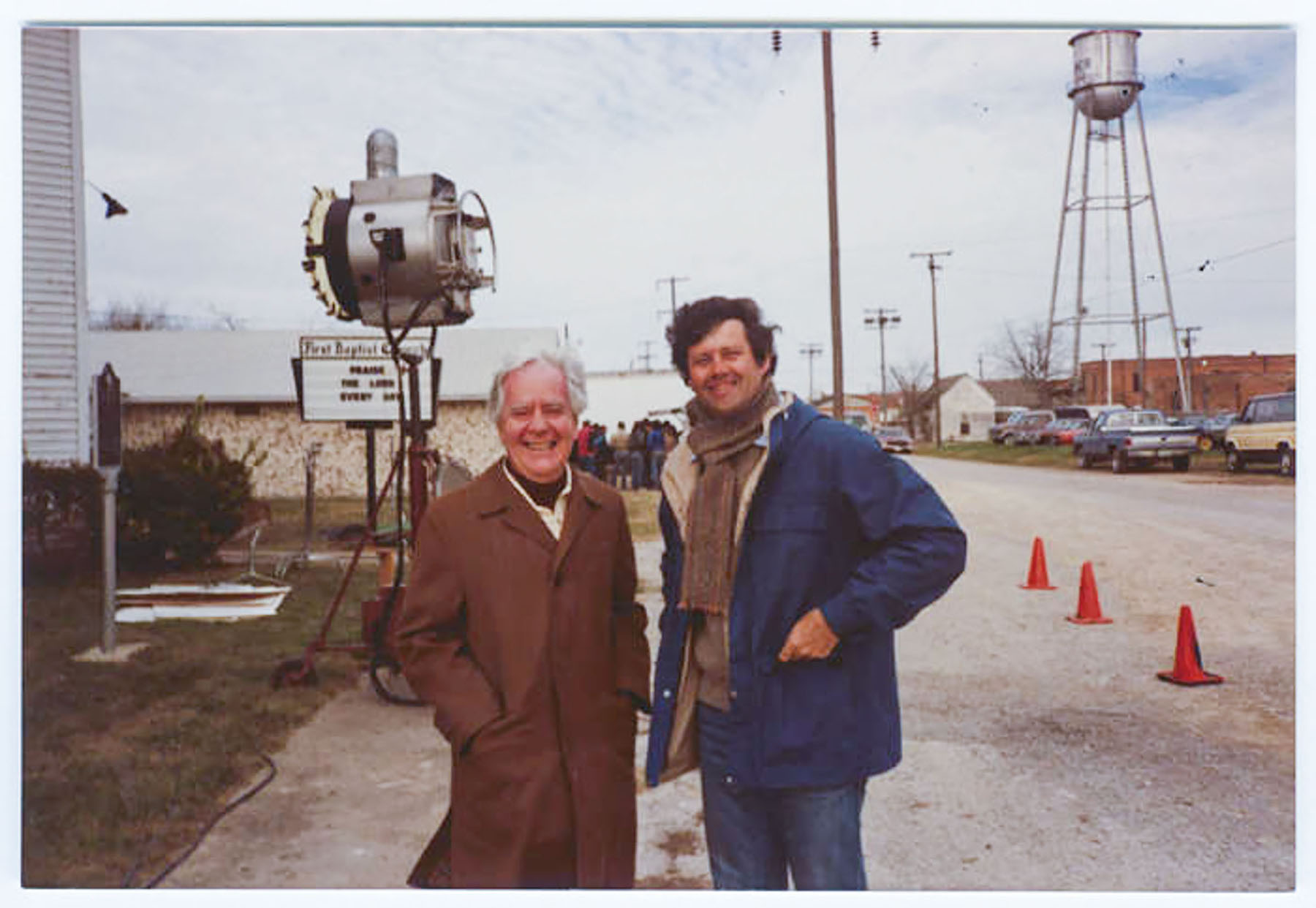

There was just one problem: The film’s producers couldn’t find a director. After a number of American directors turned down the project, the script found its way to Australian Bruce Beresford, who’d yet to make a movie in the United States. Beresford had never even been to Texas, but he instantly connected with Foote’s portrayal of Mac and his efforts to turn around his life.

“When I first read the script, I was terribly moved by it,” Beresford recalls during a recent phone interview from his home in Sydney. “Every line of dialogue—his insights into people, I thought, were really profound.” Beresford didn’t wait to finish reading the script. “I was only halfway through when I called them and said I’d do it,” he says. “I was so frightened they’d give it to someone else before I’d finished reading it.”

The farmhouse from Tender Mercies remains standing alongside FM 878 on the eastside of Waxahachie. Photo by Tom McCarthy Jr.

The little farmhouse next to the crop field became the desolate setting for Tender Mercies, an understated film that is widely considered one of the finest movies to ever come out of Texas.

Beresford flew to Texas, where Foote showed him around Waxahachie. The parallels between Texas and Australia, from the landscapes to the frontier myths, were uncanny. “It was similar to life in the Outback, with small towns and people living in small groups,” he says. They discovered the farmhouse on FM 878 about 7 miles east of Waxahachie. “It was on a highway, but it wasn’t busy. It was isolated. That was important to Horton. If it had been in the middle of a town, it wouldn’t have worked. It needed to have all that space and isolation.”

No character in the script is more isolated than Rosa Lee. “She’s lonely,” says Anne Rapp, the film’s script supervisor and a native Texan. “She lost her husband in the war. She’s out there trying to make ends meet with her little son.”

Finding an actress to play opposite Duvall proved to be a challenge. “I was casting in New York and casting in Los Angeles for a long time,” Beresford says. “I couldn’t find someone to play the girl.” Then, at an audition in Houston, he was introduced to a former schoolteacher named Tess Harper, who had arresting blue eyes but had never been cast in a movie. “I thought the Hollywood actresses were wrong for the role,” Beresford recalls. “It didn’t matter how talented they were. They just didn’t convince me. They all seemed too sophisticated. You didn’t believe the dialogue when they said it. But when Tess said it, I believed it completely. She was absolutely perfect.”

Harper, who was 31 years old at the time, had recently moved from Houston to Dallas to pursue a career acting in TV commercials, industrial training videos, and—if she got a big break—low-budget movies and TV shows. Harper had grown up in the Ozarks, and while she didn’t see much of herself in the character of Rosa Lee, she felt like she knew her. While reading the script, Harper had jotted down a single note in the margin: “And Mary watched and kept all these things in her heart,” a reference to a Bible verse in which the mother of Jesus observes and ponders a series of Christmas miracles.

“The biblical Mary was watching these things and being silent as she absorbed the world around her,” Harper explains during a recent phone interview from Los Angeles. “She wasn’t judgmental. She’s a woman who watches, who doesn’t expect miracles, who is alone on the prairie with this boy and this man. It’s not a great love story. It’s not about passion. It’s about acceptance and fellowship.”

The title of the movie is also a reference to a Bible verse from the Book of Psalms about tender mercies and “lovingkindnesses.”

“[Rosa Lee] provided a refuge to this man who was lost in so many ways, and she was there to witness the tender mercies of getting sober, of the little blessings in your life,” Harper says. “What they had was the feeling that, together, we might actually get through all this. It’s about finding peace in a world that’s not necessarily peaceful.”

The film’s producers, a married couple named Philip and Mary Ann Hobel who came from the world of documentary films, weren’t sold on Harper. They didn’t want a first-time actress for the part. Of course, they had no way of predicting that Harper would soon be vaulted into a film career that includes an Academy Award nomination in 1986, an appearance alongside Tommy Lee Jones in 2007’s No Country for Old Men, and a recurring role on the prestige TV show Breaking Bad.

“They wanted to get an actress with some sort of a name,” Beresford says. “But I said, ‘Look, it will be a big mistake if we do that.’ I insisted. I absolutely insisted we use her.”

Harper read again for Beresford in Waco. She flew to Houston and read with Duvall. She flew to New York and read for the producers. “Everyone was saying you can’t cast this person from Dallas,” Harper recalls. “He said, ‘No, she’s the girl. She’s the girl.’ And I was just one lucky blond lady with really blue eyes.”

Beresford had won the battle. By the time filming began in early November 1981, winter had already set into Waxahachie. “The fields were empty. It was just red dirt,” Rapp says. “I don’t want to say it was a depressing look, but it represented what the characters were going through.”

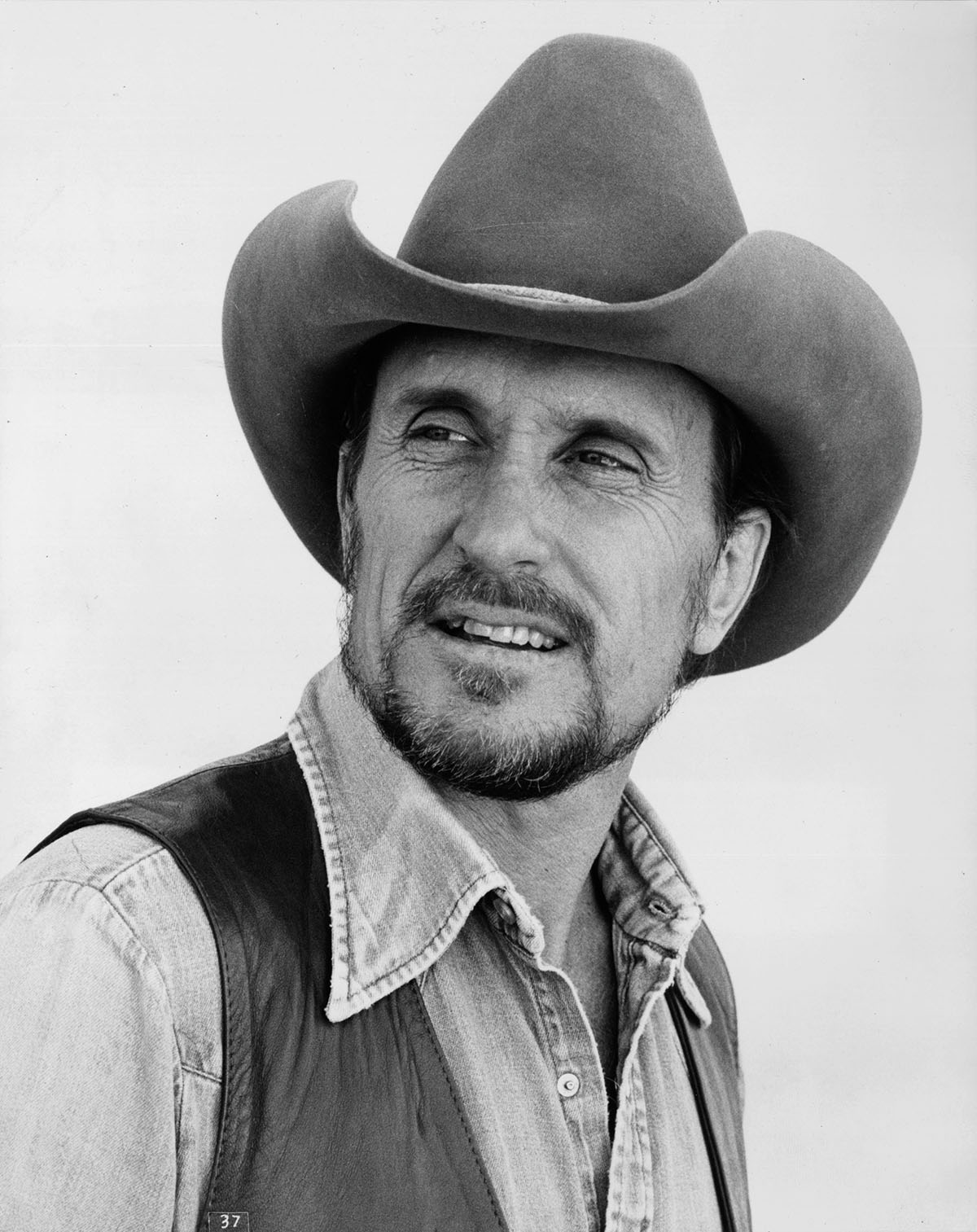

Duvall, one of the greatest character actors of his generation, was 50 years old with a face as weathered as the winter landscape. To prepare for the role, he’d spent weeks driving around small town Texas, talking to people and learning their accents. He even occasionally jammed with a country band. When he arrived on set, he embodied a Texas raconteur bedraggled from hard living.

“On the very first day of the shoot, he gets into a drunken brawl and ends up sleeping on the floor, and he’s flawless,” Beresford says. “I remember thinking, this guy’s going to win an Academy Award for this role.”

Members of the crew were also in awe of Duvall. “You could tell from the moment we got there, this was going to be something incredible,” says Jerry Callaway, a camera operator from Midland who was shooting his first major film. “Everyone knew we were making a special movie,” Rapp adds. “It was beautifully shot, beautifully acted, the dialogue was so good. We all felt like we got boosted into a much more poetic world.”

From the get-go, however, Duvall clashed with nearly everybody on set. “Bob Duvall is a great actor, but he’s often quite hard to get along with,” Beresford says. “He’s ferocious sometimes, and he’d lose his temper often.”

Robert Duvall's portrayal of Mac Sledge in Tender Mercies won him an Academy Award in 1984.

Members of the crew were also in awe of Duvall. “You could tell from the moment we got there, this was going to be something incredible,” says Jerry Callaway, a camera operator from Midland who was shooting his first major film.

The director and his star disagreed on a fundamental approach to filming the scenes. “I always felt, in fact, that Bob wanted to direct,” Beresford says. “He really likes films to be improvised, and he got very upset that I preplanned the shots. We had a script that was very specific and was written by one of the finest writers in America. Is someone going to improvise dialogue better than what Horton wrote? I don’t think so. So we should do exactly what’s written.”

Attempts to reach the now-92-year-old Duvall for comment were unsuccessful, but in the 1985 book Robert Duvall: Hollywood Maverick, he is quoted as criticizing Beresford’s approach. “He has this dictatorial way of doing things with me that just doesn’t cut it,” Duvall told the book’s author, Judith Slawson. “Man, I have to have my freedom. Make things happen with a line change or two in there.” Duvall also argued that defending one’s vision is how a film gets better. “You ever been on a happy set? Everybody loves one another? Then you see the final product and whoa, it’s a mess.”

While Duvall may have been difficult on set, he got the job done on film. “He’s one of those people, if he had a problem with something, he had great trouble verbalizing it,” Beresford says. “You’d never really know what the problem was. It was often difficult to communicate with him, but every time he played a scene, I was absolutely stunned. I thought he was brilliant.”

Duvall’s Mac Sledge is far from the only memorable character in the film. His ex-manager is played by noted character actor Wilford Brimley, whom Rapp describes as a “cranky old fart.” His ex-wife is portrayed by Betty Buckley, a former Miss Fort Worth beauty queen better known for Broadway musicals, whom Rapp describes as “all over the map, but in a wonderful way.” And Mac’s daughter is played by a young Ellen Barkin in just her second movie role.

It was an all-star cast, but Tess Harper as Rosa Lee was a revelation. The camera often lingers on her face as she silently observes Mac, communicating oceans of meaning without words. Callaway, the camera operator, recalls that Duvall purposely made things difficult for Harper on set. “He would egg her on right before the shot to get her mad, and she would react, and he’d pull that emotion out of her,” he says.

The filming of Tender Mercies wrapped in December 1981. Test screenings of the completed film were disastrous. One studio executive said the movie was “like watching paint dry.” When it was released on March 4, 1983—the spring season when studios traditionally unload their least marketable films—Tender Mercies opened in only three theaters and grossed a mere $47,000 at the box office, despite mostly positive reviews. The movie was almost immediately pulled from theaters and quickly released on cable TV—and that’s where it found a second life. When awards season rolled around, the film was nominated for five Academy Awards, including Best Picture and Best Director. In addition to Duvall’s Oscar win for his portrayal of Mac, Foote took home a trophy for Best Original Screenplay.

The writer had been a quiet presence on the set of Tender Mercies, but he managed to strike up an unlikely friendship with Rapp after learning that she grew up in the tiny Panhandle town of Estelline. “He’s the most curious man I’ve ever met,” Rapp says. “He wants to know about everyone else. He didn’t want to talk about himself. If he’s in a room, he’s either quiet, listening, or he wants to know about you.”

Rapp and Foote kept in touch until his death in 2009. For the last three years of his life, she made several trips to Wharton to interview Foote, gathering stories and remembrances for a documentary project titled Horton Foote: The Road to Home. The documentary was recently released on Apple TV and a streaming site for independent films called Projectr. Foote’s daughters Daisy and Hallie have also been collaborating with celebrated songwriter Steve Earle to adapt Tender Mercies as a Broadway musical.

The film left its mark on Waxahachie. Almost overnight, the town became a film hub for movies such as 1984’s Places in the Heart, which was directed by Waxahachie native Robert Benton and featured an Oscar-winning performance by Sally Field; and 1985’s The Trip to Bountiful, another popular film written by Foote.

“Waxahachie was kind of like the Texas backlot back then. There was just one movie after another,” says Borders, whose grandpa Marvin tried to warn the filmmakers against opening a gas station on FM 878 all those decades ago. Borders is now the director of Waxahachie’s Crossroads of Texas Film and Music Festival, which has hosted screenings of Tender Mercies. The picturesque town remains a popular film location to this day—recent projects include TV shows helmed by Yellowstone creator Taylor Sheridan.

As for the little farmhouse, it remains standing alongside FM 878 on the prairie east of town. The gas pumps and motel cabins are long gone. If you don’t know where to look, you’d probably drive right past. The walls are leaning, the white paint peeling. But it’s still there, surrounded by a sea of grass, a lonely and isolated place where it’s not hard to picture a man who’s down on his luck, looking for a second chance.