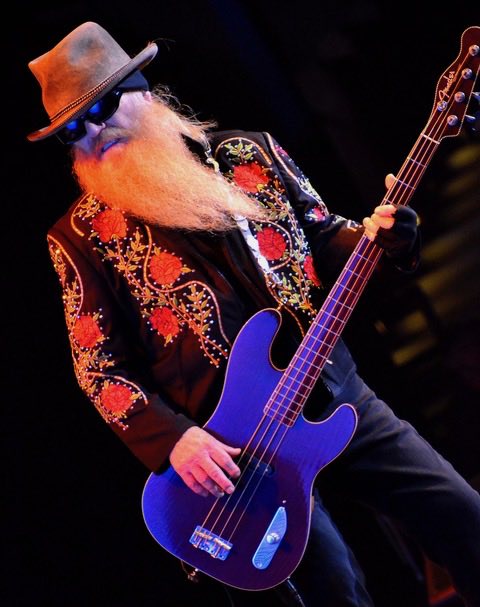

Courtesy ZZ Top, Bob Merlish

The death of 72-year-old Joe Michael Hill in Houston on Tuesday marks the end of a remarkable life in music. It also concludes the final chapter of one of show business’ most remarkable runs ever. For 52 years, the man better known as Dusty Hill played bass guitar for ZZ Top, the most durable rock band in the history of popular music. No other group of their stature lasted so long with the same personnel. Three guys playing three chords.

“Dusty understood the mechanics of a three-piece power trio,” says Cadillac Johnson, a Fort Worth bassist who played briefly with ZZ Top before Hill joined the band in 1970. “He was a perfect match for Billy Gibbons. His stage presence and choreographed interplay with Billy will never be equaled.”

ZZ Top was dreamed up in 1969 when an ambitious record promo man and frustrated singer from Waxahachie named Bill Ham met Billy Gibbons, an 18-year-old guitarist with the Houston psychedelic rock band Moving Sidewalks. They met backstage at a gig where the Sidewalks were opening a concert for The Doors.

Ham’s idea was solid, but the band was not. Drummer Dan Mitchell came with Gibbons from the Moving Sidewalks. Lanier Greig, a keyboardist from another hot Houston band, Neil Ford and the Fanatics, sat in on bass. The ensemble recorded a 45 rpm single in Tyler, “Salt Lick,” on Ham’s independent label, Scat Records. The record failed to stir up much attention, and Ham replaced Greig and Mitchell with bassist Billy Etheridge and drummer Frank Beard. Etheridge was fired (allegedly for being a bad influence on Beard). That’s when Beard called Dusty Hill.

After calling for—and then playing—a shuffle in the key of C on a borrowed bass with Gibbons and Beard, Hill was hired. The ensemble debuted on February 10, 1970 at the Beaumont VFW Hall. Later that year, London Records released the self-explanatory ZZ Top’s First Album.

Adding Dusty Hill completed Ham’s vision. He was the old-timer in the band, the pro who had been around and tasted some modicum of success. More significantly, he brought the mojo. Gibbons was an extraordinarily talented guitarist in the rock idiom and a natural showman. Hill (and Beard) knew how to rock too, but also had extensive experience playing authentic blues, having backed up blues icons Freddie King, Lightnin’ Hopkins, and Jimmy Reed.

In a business where the blues was a sound mostly learned from records by mysterious musicians, Dusty Hill had the benefit of direct transmission: He didn’t just emulate blues masters’ records, he had played and interacted with the blues masters.

Other power trios were circulating around rock arenas at the time, notably Grand Funk Railroad, the James Gang, and the Johnny Winter Group—all influenced by the prototypical power trio Cream, headed by Eric Clapton, and by the Jimi Hendrix Experience. But no other power trio created such an authentic sound built on a strong blues foundation, and none expanded and reinvented their original sound like ZZ Top.

Their breakout third album, Tres Hombres, released in 1973, put ZZ Top on the map. Two years later, the band’s “World Wide Texas Tour,” featuring the musicians decked out in sparkly Nudie cowboy outfits with Hill and Gibbons doing tightly choreographed steps and a live buzzard and live Longhorn on stage, established the band as a top draw on the rock concert circuit. The First Annual Texas Size Rompin’ Stompin’ Barn Dance and Bar B Q at the University of Texas Memorial Stadium in the fall of 1974 drew 80,000 sweat-soaked fans to an all-day affair that also included Santana, Joe Cocker, and Bad Company (featuring Led Zeppelin’s Jimmy Page on guitar).

Dusty Hill already had built up quite a rock ’n’ roll resume when he signed on with ZZ Top. He started playing bass at age 13 and hit the road to play gigs a year later. A student at Woodrow Wilson High School in Dallas, he dropped out at age 15 to play with a band called the Deadbeats. In 1966, Dusty and his guitar-playing brother, Rocky, and drummer Beard formed the band The Warlocks in Dallas. They quickly became regulars on the notorious Cellar Circuit, playing the afterhours clubs in Fort Worth, Dallas, and Houston. “I mean, there was free booze and women, and there I was, 19 years old,” Rocky Hill later recalled.

The Warlocks appeared on the Panther A Go Go television show from Panther Hall in Fort Worth, backed Dallas rocker Scotty McKay on several recordings. They were also the backing band for touring musicians including Cannibal and the Headhunters, as well as Texas blues icons Freddie King and Jimmy Reed.

Barely getting by, the Warlocks reinvented themselves as American Blues, a psychedelic blues-rock ensemble who died their long hair blue. American Blues recorded two albums, one for Uni Records, and released a single, a psychedelicized send up of the Tim Hardin folk song “If I Were a Carpenter.”

Two years of blue hair proved enough. The band broke up and Dusty and Rocky moved to Houston together. “We hocked our stereo for $30, got on a Greyhound, and hit Houston broke,” Rocky Hill said. The brothers went their separate ways.

Rocky wanted to play blues and started working with Lightnin’ Hopkins. Beard, the American Blues’ old drummer, suggested Dusty try out for ZZ Top.

As a bassist, Hill did not play lead, but focused instead on rhythm and laying down the foundation to each song. Hill didn’t sing. He wailed in a tortured tenor, the perfect complement to Gibbon’s John Lee Hooker growl, evidenced by Hill’s vocal turns on “Tush,” “Beer Drinkers and Hell Raisers,” and “Party on the Patio.”

ZZ Top took a break in 1977 after seven years of constant recording and touring. During the hiatus, both Hill and Gibbons grew beards. When the band resurfaced, they had a new look, the two front men resplendent in matching sunglasses and long beards—a look that rendered the band ageless for the rest of their careers.

Sonically, they recalibrated with a New Wave-y synthed-up sound that was made for MTV music television with 124 beats per minute—an ideal dance groove—and plenty of eye candy to look at in their videos. Hill played keyboards in addition to bass.

“The reaction was like when Dylan went electric,” Dusty told me for a 1996 story in Texas Monthly magazine. The “little ol’ band from Texas” that could boogie till your pants fell off was now all about hot rods and babes, framed in modern, danceable context. The formula worked. Eliminator, released in 1983, spawned ZZ Top’s biggest hits yet—“Sharp Dressed Man,” “Gimme All Your Lovin’,” and “Legs.”

Since their 1980s MTV renaissance, ZZ Top has persisted to the here and now, steadily recording albums and touring the world. The band parted ways with manager Ham and Lone Wolf Management in 2006, freeing up Billy Gibbons to sit in with other bands and make his own recordings, in addition to working with ZZ Top. Hill stayed in communication with Ham and sought to reconcile their differences all the way until Ham’s death in 2016, Hill’s wife, Charleen McCrory, told me at an informal memorial for Bill Ham at a Lake Travis steakhouse.

“People in New York and L.A. have made Ham out to be a dimwit, and they’ve paid dearly,” Hill told me in 1996.

While Gibbons has become an even more visible public figure since the split with Ham, Hill preferred fading into the background whenever he wasn’t being one-third of ZZ Top. A big Houston Rockets fan, he once shared season ticket seats with Compaq computer CEO Eckard Pfeiffer and socialite Carolyn Farb. He was a party bud of his neighbor, one-time Houston Astro star Ken Caminiti. He dug riding Harleys and vacationing in Mexico.

Following a pandemic pause of more than a year, ZZ Top hit the road again in July. On July 21, the band announced Hill was headed back to Houston to deal with a hip issue. The bassist had previously had hip replacement and shoulder surgeries and suffered a gunshot wound to his stomach in a 1984 shooting accident.

“Let the show go on!” Hill declared in a ZZ Top press release, announcing his departure. Filling in would be guitar tech Elwood Francis. Hill passed away in his sleep the evening of July 27. The band did not release the cause of death.

ZZ Top may continue in some form or reconstituted lineup. But the Little Ol’ Band from Texas that raised arena roofs while also raising several generations on pure Texas blues rock is no more.