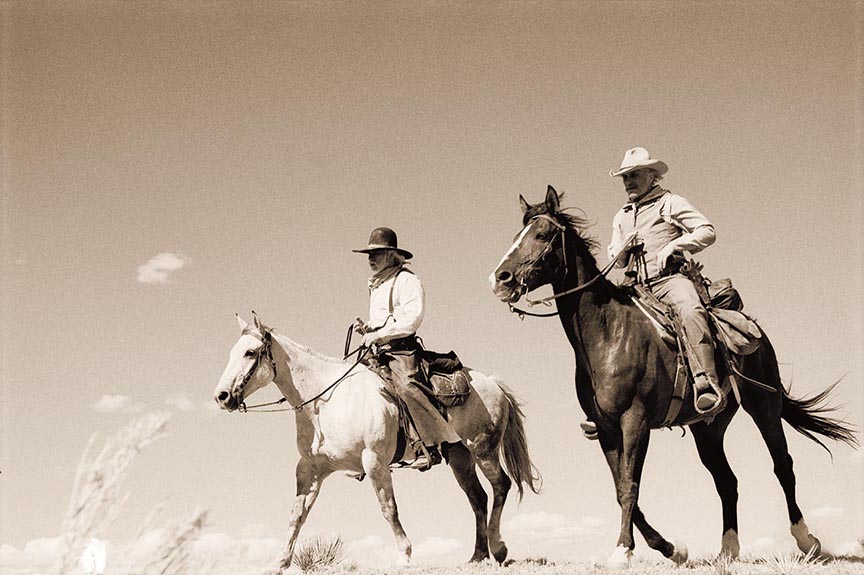

The photo ‘On the Mesa’ by Bill Wittliff features Tommy Lee Jones (left) and Robert Duvall. Photo courtesy of The Wittliff Collections, Texas State University.

In January, I was able to catch Lonesome Dove—not the miniseries but the traveling exhibition produced by the Wittliff Collections at Texas State University in San Marcos. This collection of photographs has been touring the state since 2017, but the first stop on its 2021-22 jaunt was at the Freeport Historical Museum, located in the city’s tiny but charming and resurgent downtown. If you haven’t seen the exhibit yet, go. The tour continues in Irving starting March 6, then heads to Temple and Claude.

The exhibit’s 55 black-and-white character portraits and action shots were captured by Bill Wittliff, who adapted the novel by Larry McMurtry and co-executive produced the award-winning 1989 miniseries. Wittliff’s great genius on the TV project was in adhering his teleplay as strictly as possible to the text, and the result was quite simply one of the 20th century’s greatest adaptations. It’s that rare “movie” that’s as good as or better than the book. (It was technically a miniseries, but I’ve binge-watched it enough to where I just think of it as a 384-minute film).

While on the set, Wittliff apparently stayed out of the way of director Simon Wincer and busied himself with his camera, and the results are stunning. You don’t feel like you are looking at pictures from a film set. You don’t feel like you are looking at pictures from the late 20th century either. Wittliff’s photos have a look very much like those illustrated volumes in the faux-leather Time-Life Old West series, but they exceed them in some ways.

Alongside the photographs are quotes on placards from McMurtry and others, including author and Texas historian Stephen Harrigan. “Lonesome Dove is a great book that had the rare fortune of being made into a great movie,” he says. “I think there is now a third generation of Lonesome Dove artistry. The pictures that Bill Wittliff took on the set of the movie have a standalone ghostly authority. The same creative power and conviction that allowed Larry McMurtry to transform his workaday scenario into one of the greatest novels of our time, and that transformed that novel into one of the greatest Western movies ever made, are on display in Bill Wittliff’s photographs.”

Part of it is technological. Obviously, the curtained, massive flash bulb cameras of those days were no match for Wittliff’s 1980s point-and-shoot model. Therefore, the character portraits of rangers Call (played by Tommy Lee Jones) and Gus (Robert Duvall), the tough-but-vulnerable Lorie Darlin’ (Diane Lane), and the terrifying Blue Duck (Waxahachie native Frederic Forrest) are all looser and more natural than anything that could have been captured in the old days, when slow exposures required portrait subjects to freeze stock-still for up to a minute.

And action shots like the sort seen in this exhibition were downright impossible for the camera to capture back then—hence the popularity of Western painters like Frederic Remington, Charles Schreyvogel, and Charles Marion Russell. Working from sketches and their imaginations, they could depict thundering herds, gunfights in full swing, and the horseback derring-do of the cowboy and Comanche and Sioux alike in such a way that contemporary photographers could not.

By the time Lonesome Dove was made, that was no longer the case, and Wittliff’s camera captured photos that look very much like, and in some cases even surpass, Remington’s.

“That’s what’s beautiful about Bill Wittliff’s photography, they do look like they came from the late 1800s,” says Wade Dillon of the Freeport Museum. “Even the character shots of Tommy Lee Jones and Robert Duvall, but even more, action shots like the one of the cattle herd getting scared, as we see [in one of the photos].”

“Stolen Horses” by Bill Wittliff, shot in 1988. Photo courtesy of The Wittliff Collections, Texas State University.

Dillon and I share a favorite image: an extreme wide-angle shot of Gus McCrae on the High Plains in retreat from Blue Duck’s ragtag band of Kiowa and Comanchero henchmen. In the scene, the Texas Ranger fires wildly behind him through a cloud of dust with his Colt Walker, just before he is forced to yank his horse to the ground in a slight depression, slit its throat, and use its carcass as an impromptu fortification. Fans of the series remember the rest—he holsters his Colt, unsheathes his Henry 1860 long rifle, and clinically dispatches two or three of his antagonists before they beat a retreat and then lay siege with a Sharps buffalo rifle.

Such reveries are produced by looking at Wittliff’s photos. As you gaze upon them, you hear the magisterial score of composer Basil Poledoris piped in through the museum’s speakers, the soaring Aaron Copland-like swell of the series’ main theme song, and the jaunty brass pomp of “The Leaving,” as Call and McCrae point their 2,000 steers north.

These photographs conjure once more the majesty of the novel and miniseries, considered by popular consensus the most beloved work of art in those categories in Texas history. I contend that it qualifies as, well, if not the Great American Novel, it’s darn close to it. It’s one that will be cherished and read and debated as long as Huckleberry Finn or any other contender you care to mention. Like that work, it’s geographical sweep is country-sized, albeit northbound on a cattle trail instead of southbound on a river.

At its central conceit—Call and Gus as the Texan Don Quixote and Sancho Panza—the story of Lonesome Dove harkens all the way back to the origins of modern Western literature. (By which I mean the sweep of Euro-American literature, not the American Old West.) And the construction of its plot is ingenious: A single stray bullet from a feckless man set in motion an epic cattle drive that claims dozens of lives along the way. Incident piles upon incident, doomed love affairs abound—couples come together as often by happenstance as by passion. Such was life then and such is life now, as Wittliff’s old friend and artistic collaborator Willie Nelson once put it in another context: “Ninety-nine percent of the world’s lovers are not with their first choice. That’s what makes the jukebox play.”

Ultimately, Lonesome Dove is the sort of work that reminds you of people you know, want to know, or want to be. I’m guilty of the last, as I consider Gus McCrae is a role model of mine (although I fall short in most matters). For Wittliff, who passed away in 2019, it was the first of these. As Wittliff is quoted on another of the exhibit’s placards: “There’s a view about great art, whether it’s stories, poetry, music, whatever. None of it tells you anything new; it merely reminds you already knew but forgot you knew. And that’s what Larry did. You start reading Lonesome Dove and you feel you already know these people. They’re already in you. They’ve always been in you. That’s it’s great magic.”

The Lonesome Dove exhibit is presented in partnership with Humanities Texas, the state affiliate for the National Endowment for the Humanities. It’s on display in Irving from March 6 to July 11 and moves to the Temple Railroad Heritage Museum in Temple and the Armstrong County Museum in Claude in 2022.