Big Bend wanderers, celebrities drifting down from Marfa, and other end-of-the-liners have officially discovered the border town of Presidio. They’re late by about eight centuries, though: People have lived for so long at the confluence of the Rio Grande and the Rio Conchos that the valley surrounding Presidio is thought to be the oldest continually cultivated farmland in Texas, if not the United States.

“It’s funny,” says John Ferguson, the mayor of this dusty town 60 miles south of Marfa. “Presidio is the oldest town anywhere in the entire Big Bend area, but so little of our history is truly known, even to those of us who live right here on top of it.”

The valley surrounding Presidio is thought to be the oldest continually cultivated farmland in Texas, if not the United States.

It’s late March, and Ferguson’s family and I are digging into platters of enchiladas and shrimp diablo in Ojinaga, the Mexican sister city to Presidio. The week prior they’d done this very thing—dined with a curious traveler in an Ojinaga restaurant—but their guest then was Anthony Bourdain, the celebrity chef, author, and television personality, who died last June. Bourdain had been on a tour of the farthest corners of West Texas for his CNN megahit Parts Unknown.

But Bourdain, who quickly dashed off for Big Bend, missed what was the best part of my Presidio/Ojinaga experience: riding bikes across the border from Presidio with Ferguson—who looked at ease aboard his ’30s clunker with high-rise handlebars—and his wife, Lucy. When you ride bikes with the mayor from bakery to plaza to mezcalería—regardless of which side of the Rio Grande you’re on—you can’t go 10 yards without someone waving, “Hola, Señor Ferguson!” Even the border patrol agents, as we pedaled cautiously across the bridge, gave him a salute.

And it’s not just because he’s the mayor of this palm-lined outpost The Washington Post identified as the sixth-most-isolated (“middle of nowhere”) town in the country last year. Ferguson is also the school counselor at Presidio High School, where Lucy, a trombone player, teaches band. With their two kids, the Fergusons have their own family mariachi band, Mariachi Santa Cruz, which plays regularly on both sides of the border, and a funky fusion band, The Resonators. The Fergusons’ daughter, Molly, whose boyfriend lives in Ojinaga, sings Tejano songs with such soul and authenticity that she won the Austin Tejano Music Coalition’s 2017 Tejano Idol award.

This kind of cultural commingling is the norm in Presidio, population 5,106, where most lines between “us” and “them” are happily nonexistent. And you don’t have to go cycling with the mayor to pick up on that. Check out the Presidio water tower, where Los Angeles muralist Miles “El Mac” MacGregor has painted a striking portrait of a woman gazing upon Ojinaga. This 2018 gift of public art from Mexico to the Mexican Consulate in Presidio sends a compelling message—good neighbors look out for each other.

Unlike residents in some Texas border towns, no one in Presidio shies away from Ojinaga; the towns feel like one community, and with a population of about 28,000, Ojinaga is for many Presidio residents the preferred side of the border for grocery shopping and dining out. Ojinaga has seen relatively little cartel violence, and it feels safe to locals; the flow back and forth across the border is a normal part of daily life. As Presidio County Attorney Rod Ponton told me one night in Ojinaga over dollar margaritas, “Presidio without Ojinaga is like San Antonio without the south side, without the missions. They are inseparable.”

If you’re just passing through Presidio—and most travelers are—it’s easy to get the wrong idea. You won’t see hip galleries or boutique hotels, and things can seem a bit, um, too quiet. But if you slow down, stick around, and keep an open mind, you’ll see the life beneath the surface, a life that is not quite the United States and not quite Mexico, but an in-between character you won’t find anywhere but the border. I got a glimpse of it in St. Francis Plaza, a stucco-walled town square dedicated to the Franciscans who first established a mission in Presidio/Ojinaga in 1660. It was here during an outdoor concert, part of Presidio’s Bluebonnet Music Series, that musician Chet O’Keefe told me, “I tried living in Austin, but it wasn’t my thing. I like Presidio—it’s the people. There’s a real community here, and that’s what matters.”

“Presidio without Ojinaga is like San Antonio without the south side, without the missions. They are inseparable.”

Stop in for lunch at the friendly Bean Cafe, and you’ll see what he means. Chances are owner Hector Armendariz will come by to say hello while his wife, Sonia, keeps the plates coming. This buzzing gathering spot is where you can catch half of Presidio during the lunch hour—high school staffers, border patrol agents, tourists passing through from Big Bend Ranch State Park, or bikers who just cruised the wonderfully scenic River Road (FM 170) that heads east along the Rio Grande to Terlingua.

“We may have placed in the top 10 middle-of-nowhere towns, but it’s a really cool middle of nowhere,” says Brad Newton, the executive director of the Presidio Municipal Development District, as he cuts off a wedge of the “Brad Burger” to share with me. Topped with asadero cheese and green chiles, it’s a finger-licking mouthful.

The Bean sits about a mile east of one of West Texas’ busiest routes, US 67, which connects Presidio with the towns of Fort Stockton, Alpine, and Marfa. But few navigate the southernmost stretch of 67, where artsy Marfa fades in the rearview, and the remote path down to Presidio opens up. Making the drive, I keep my eye out for a pair of unusual formations: the Elephant Rock, chunks of volcanic rock in the shape of an elephant about 15 miles south of Marfa; and the Profile of Lincoln, which is weathered into the Chinati Mountain Range to the west (Abe Lincoln’s profile, looking heavenward, is unmistakable). It is refreshingly quirky that these natural sculpturesque landmarks have been significant enough to be given their own highway signs.

About 20 miles north of Presidio, I pass Shafter, a mostly deserted former silver- mining town strewn in crumbling adobe. Shafter’s Catholic church—with its proud white steeple visible from the highway—still celebrates Mass every third Sunday of the month. All other days, Shafter is mostly silent, although trucks from mining companies occasionally drive in and out, signs of renewed hope for riches.

To get a better sense of Shafter’s heyday in the early 1900s, I take a quick detour and wind past Cibolo Creek, which is parched but lined with cottonwoods, a desert signpost that water is nearby. Soon I arrive at a cemetery dotted in wooden crosses and the homegrown Shafter museum. This is a treasure worthy of exploration on foot but rocky and prickly enough to make me wish I wasn’t wearing sandals. I pause for a moment in one of the tiny, timeworn chapels in the cemetery, and the truth behind words etched onto one tombstone hits home: “Thank you, Lord, for this wonderful world, and for the times out here when we can best hear you speaking to us.” Amen.

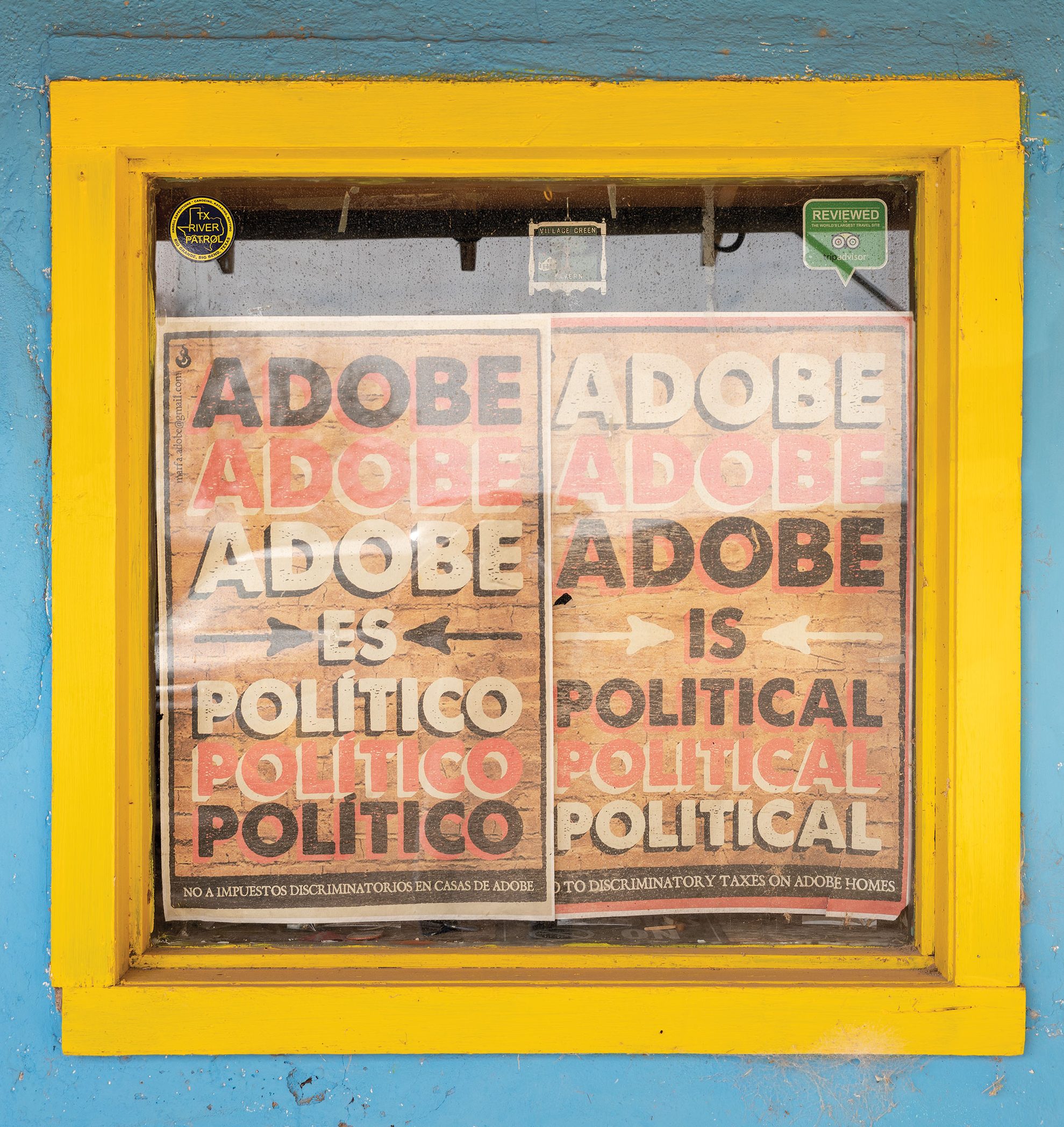

After my cemetery idyll I pull into Presidio, where I immediately see a bumper sticker on a truck that reads, “Adobe is Political.” These are words originally attributed to Simone Swan, director of the Presidio-based Adobe Alliance, and a reminder that for many locals, adobe is much more than mud—it’s a calling to build low-cost and sustainable homes using indigenous building techniques.

Fort Leaton State Historic Site

Probably the most stunning public adobe building in Texas is the Fort Leaton State Historic Site, 5 miles east of Presidio on the River Road. Not only can you marvel at the handsome interior spaces kept cool by thick earthen walls, but the museum here teaches nuggets of local history and ecology: how this area was once called La Junta, or “The Joining,” because it’s where the Rio Grande and the Rio Conchos join together; about the Jumano and Mescalero Native Americans who once thrived here; and about Presidio’s role in the Mexican Revolution. It also gives you the lowdown on the fort’s former owners: Ben Leaton, a trader and scalp hunter, and his lover, Juana Pedrasa. Theirs was a mid-1800s saga of love and murder worthy of a Cormac McCarthy novel. Road-weary travelers, bounty hunters, and gold seekers all found shelter in this adobe masterpiece, and their spirits seem to linger.

Fort Leaton is also a check-in center for Big Bend Ranch State Park, another Presidio-area draw with infinite possibilities for outdoor rambles. If these 486 square miles of exquisitely austere parkland with bumpy roads, rattlesnakes, and almost no cell coverage feel a little intimidating, call Charlie Angell, a guide who’s lived just outside of Presidio since 2001. His company, Angell Expeditions, leads hiking, biking, and Jeep driving tours around Texas’ biggest state park, as well as tours of Ojinaga and raft trips. Angell is also on the board of Compadres del Rancho Grande, a nonprofit that supports the park, hosts the Big Bend Ultra trail race, and gets local kids involved in activities like the Fort Leaton youth docent program, awarding scholarships to kiddos who excel.

Charlie Angell of Angell Expeditions on the Rio Grande.

A few days before I arrived in Presidio, Angell, too, happened to be showing Bourdain the wonders of the region on an overnight river excursion through Santa Elena Canyon in Big Bend. “Bourdain was great,” Angell says. “And, even though he hardly cooked anymore, I got him to make us an omelet for breakfast. It was quite good.”

There will be even more wild terrain to explore near Presidio when Chinati Mountains State Natural Area opens for public use. This 38,137 acres of desert west of Chinati Peak will be accessible from the River Road that leads northwest from Presidio toward the Chinati Hot Springs. Once the park is funded, it will offer primitive camping and mountain hikes, providing more pull toward Presidio for outdoor adventurers who like to rough it.

“We may have placed in the top 10 middle-of-nowhere towns, but it’s a really cool middle of nowhere”

For some urban dwellers, just coming to Presidio at all might feel like roughing it, never mind sleeping in a tent in the middle of a desert without cell phone service. As Presidio City Manager Joe Portillo points out, the town is more than 150 miles away from the nearest piece of fast-food chicken. But the mole enchiladas at Presidio’s El Patio Restaurant—the owner’s grandmother’s recipe—more than make up for the absence, and besides, who doesn’t need a break from chain restaurants, strip malls, and the clutter of cities? When you wake up in Presidio, you may not be able get a Starbucks coffee, but you can smell the dry sweetness of creosote in the air and see the mountains tinged pink over the twinkling lights of Ojinaga to the south.

“I had to come back,” says Portillo, who worked in Austin for many years. “There is nothing quite like it. The sunrise, the desert when it comes awake in the spring.” In other words, sometimes the middle of nowhere is exactly what we need.

Where to Stay in Presidio

The Three Palms Inn has a vintage 1970s vibe with clean, inexpensive rooms and a swimming pool to beat the desert heat. The palm-flanked motel has long been the favorite of hunters, bikers, and campers passing through town.

432-229-3211

If the Three Palms is booked up—construction of a new international bridge keeps the hotel busy during the week—there is also the simple Riata Inn.

432-229-2528

Seek a healthy remove from civilization in the cabins at the Chinati Hot Springs 37 miles north from Presidio, where you can soak before you sleep.

432-229-4165

Big Bend adventure guide Charlie Angell converted the old La Junta General Store into a three-bedroom vacation home at the Ruidosa Ghost Town Inn on the road to the hot springs.

432-384-2307