By Ian Dille

Photographs by Theresa DiMenno

A Ripple in Still Water

An extended family peels back the layers of Onion Creek—and themselves

Lindy and Lyla near the eastern terminus of Onion Creek.

The promise of an oasis

led us here beneath Interstate 35, where the Old San Antonio Greenbelt borders the edge of Onion Creek. It was Easter weekend in 2020, but we weren’t gathering. A month into the pandemic, still unsure how to interact safely, we sought spaces mostly absent of humans.

I guided our old minivan under the freeway overpass, and we rumbled down toward the creekbed. My two kids—my son, August, and daughter, Lyla, then 6 and 3—looked bewildered in the backseats. Where’s dad taking us this time? The concrete stanchions supporting the tall interstate bridge make an apt canvas for graffiti artists. But I’d done my due diligence researching Onion Creek, among the longest in the state and one of the most environmentally sensitive waterways in the Hill Country. I knew a potential paradise lay at the water’s edge.

Walking closer, the gurgling creek eventually drowned out the sound of the vehicles overhead. From under the shadow of the overpass, we emerged onto an expansive limestone plateau, bleached white by the blazing sun. August spread his arms wide and ran toward the clear, cool water. I breathed deeply and took in the scene: cypress trees mirrored by still pools, herons plucking fish from gentle rapids, wispy clouds high in the sky.

Onion Creek wasn’t our first option for a retreat. Like a lot of families forced outdoors during the pandemic, my wife, Lindy, and I initially gravitated toward Austin’s revered waterways. Barton Creek and Bull Creek, with their sculpted swimming holes and picture-perfect waterfalls, are most often associated with the capital city. But those green spaces quickly became overrun. We’d set up camp on a rocky beach at Bull Creek and not long after the kids had waded into the water, the 20-somethings would arrive. You’d see one crashing down the bank with a hibachi grill, waving to his friends who toted Bluetooth speakers and beer-pong tables: “Guys, over here!” Eventually the city closed the greenbelts, citing the crowds.

We sought out lesser-known spaces to splash and explore, like Blunn Creek in Travis Heights and Country Club Creek in southeast Austin. The kids would arm themselves with nets and buckets, intent on capturing new friends. Each creek earned a nickname: Crawfish Alley and Fish Creek, then not long after the tadpole spawn, Frog Creek, Toad Creek, and Frog Creek Jr. But Onion Creek, above all others, became our sanctuary during the pandemic. And for one member of our family, it provided salvation.

Traveling 79 miles from its headwaters near Johnson City, Onion Creek cuts a wide, lumpy valley through the Hill Country southwest of Austin. The 20 creek miles east of Dripping Springs are some of the Hill Country’s most ecologically important. Along this stretch, fissures in the limestone recharge as much as 40% of the water in the Barton Springs segment of the Edwards Aquifer. At the wide mouth of Antioch Cave, near Buda, the waters of Onion Creek form a whirlpool as they’re sucked down into the earth.

While few parks exist along this first half of Onion Creek, a variety of businesses offer access. You can dine at the upscale Tillie’s Café, sleep at Sage Hill Inn & Spa, enjoy live music at Buck’s Backyard, and sip cider at the Texas Keeper taproom. The YMCA’s Camp Moody, just downstream from Buda, is “an educational tool, as well as a place for recreation,” according to Director Bret Kiester. Each summer, nearly 400 daytime campers swim, fish, and kayak in the creek while helping test the creek’s water quality. “They learn about watersheds, point-source pollution versus nonpoint-source pollution, and do creek clean-ups,” Kiester said. Camp Moody’s staff uses Onion Creek and the bordering 85 acres as an entry point to wildlife ecologist Aldo Leopold’s theories on the land ethic and our collective responsibility to the natural world.

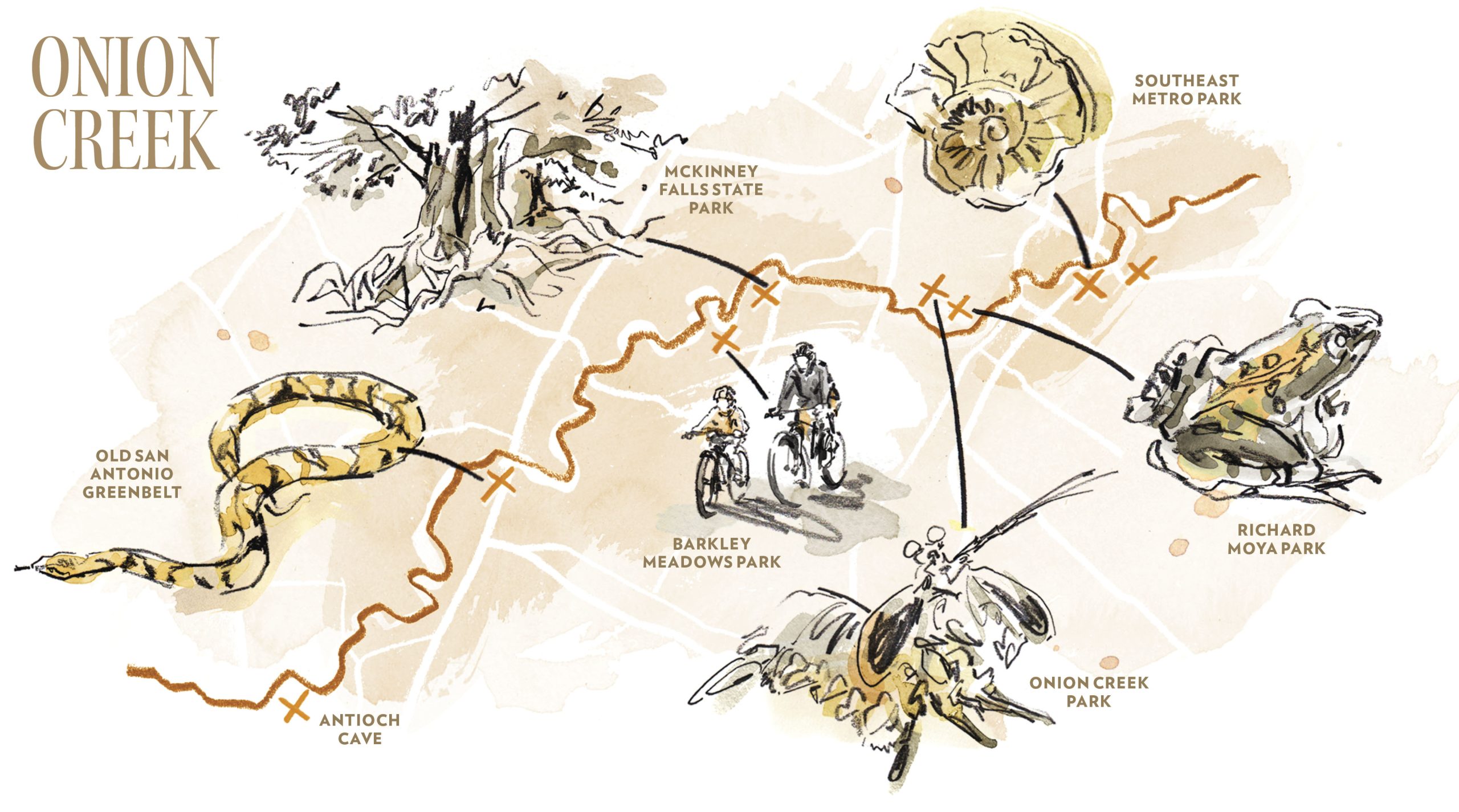

From Buda, Onion Creek flows along the southern edge of Austin to its terminus at the Colorado River in the Blackland Prairie east of Longhorn Dam. This section of Onion Creek is shaded by a tall tree canopy and lined by more than a half-dozen city, county, and state parks: Onion Creek Park, McKinney Falls, Richard Moya, and Barkley Meadows, among others.

Walking the wooded, crushed granite trail in Onion Creek Park one afternoon, I met Ana Aguirre, a community activist whose three kids grew up exploring creek greenbelts here in southeast Austin. Nearly 1,000 homes used to exist along this portion of Onion Creek, she explained to me. But floods in 2013 and 2015 decimated the neighborhoods, leaving seven people dead. “We’re still traumatized by those storms,” Aguirre said. “When it starts raining, people leave.” They find higher ground. Still, she calls this creek’s green space a blessing. “What does the creek mean to you?” I asked. “Barbecues!” she replied.

Illustration by Heather Gatley

Each member of my family became fascinated by different elements of Onion Creek. At Southeast Metropolitan Park in eastern Travis County, my wife and daughter hunted for fossils below a 100-foot cliff wall. With each rain, the cliff’s clay-based soil erodes, revealing cretaceous-era treasures that tumble into Onion Creek. Lyla developed a keen eye. In unicorn-themed water shoes and a frilly swimsuit bottom, she’d reach down into the rocky creek and reveal an Exogyra texana, an ancient oyster the size of a melon and 60 million years old. She wasn’t the creek’s first amateur archeologist. In the 1930s, geology students from the University of Texas unearthed an ancient sea monster, the Onion Creek Mosasaur, now displayed in the Texas Memorial Museum in Austin. My family’s discoveries weren’t museum-worthy, but they still left us spellbound. When Lyla held up a handful of calcified snails, dating to when dinosaurs roamed the earth, we got a little glimpse of our insignificance amid the immensity of the universe.

August’s obsession with Onion Creek revolved around living things. Quick with his net, he studied minnows and baby fry fish, lizards, turtles, and insects. A previously unknown-to-us species, the mantis shrimp, lived up to its nickname, the “thumb splitter,” derived from its powerful mandibles. We henceforth left it undisturbed. Snakes, as well, got a pass. Though I don’t endorse removing anything other than trash from Onion Creek, I do confess we allowed August to bring home a thumbnail-size Gulf Coast toad from Richard Moya Park. Initially, the toad was to stay at our home just a day or two, but August’s affection for the amphibian proved compelling. We acquired a 10-gallon tank, and August researched toad habitats on YouTube. He’d lower a palm full of earwigs and beetles into the tank, and the toad would hop over, extend its sticky tongue, and snap the insects from his hand. Big Toader, the name our family’s pandemic pet grew into, now occupies privileged space in our living room. At night, as my wife and I watch Netflix, Big Toader sometimes emits a low, seemingly satisfied croak.

My wife’s brother, Rob, first came to Onion Creek with us in May of 2020, not long after moving into our home. A professional bassist who’d grown weary of playing wedding gigs, he’d recently been dumped by his longtime girlfriend. Amid the pain, he finally confronted his addiction to alcohol. He entered a rehabilitative center just as the pandemic set in and, six weeks later, reemerged into a silent world. He needed work, and we needed childcare. But Rob wasn’t sure if he could like kids.

Lyla didn’t give him much choice. She called him “Aunt Rob” (hey, she was 3) and demanded his attention. On that initial trip, we took Rob back under I-35. It was a Sunday morning, and a few other cars were parked below the bridge. Another extended family had gotten there before us and had just finished fishing in Onion Creek. As the family’s kids played in a small pool, the men gutted their catch. They threw the fish entrails into the creek and let them wash downstream.

Lyla took off down the stone bank of the creek, and Rob followed. A gentle giant—6 feet, 5 inches, with long, strong fingers—Rob reached down and took Lyla’s tiny hand in his. As they walked along the slick limestone creekbed, Rob motioned to me, smiling: “Take a picture.” The next day, in his Alcoholics Anonymous meeting, he would share his visit to Onion Creek with the group. He explained how it awakened him to the possibilities of a world without booze. Prior to his recovery, he’d need a beer or five to start a day early, lest he find himself dry heaving from withdrawal. In sobriety, he experienced a child’s wonder: August, discovering a translucent blue crawfish beneath a wide, smooth stone; Lyla, laying out to dry, unperturbed by a half-dozen sparkling dragonflies resting on her outstretched arms.

Soon, Rob was watching the kids full time. The summer sun came, but public pools remained closed. So, he would pack snacks, swim gear, and fishing tackle, then begin debating August and Lyla about the destination of their daily creek outing. An avid bass fisherman, Rob trained the kids in the art of casting. At 3, Lyla could cast, hook, and reel in sunfish without assistance. August sought largemouths, and he quickly graduated from live worms to artificial lures. My heart burst as I watched him wait for a timid creek bass to take a plastic worm, calmly tighten the line, and firmly set the hook.

Rob, too, gained invaluable skills. He deeply feared wiping a child’s bottom. But inevitably Lyla had a bowel movement, and Rob’s mind was opened to what he could accomplish. As happens when caring for kids, at times Rob experienced moments of anger and frustration, of being overwhelmed. But he reached for a lesson from AA—to pause. The kids came to respect Rob. When August started virtual first grade in the fall, Rob facilitated the online classes and assignments. To our collective amazement, August learned to read, add, and subtract. When August eventually went back to school in-person, Rob focused on a new career. He said he wanted to continue working with kids as a bass guitar instructor.

Rob explained to me that during his time in Onion Creek he’d come to see his addictive tendencies as being rooted in human selfishness. In nature, in education, he’d found a spiritually higher purpose. He’s been sober for more than two years now.

One tip for enjoying Onion Creek is maintaining a cognitive dissonance to the pollutants that can accumulate there. Though the creek is regularly tested by city of Austin officials and deemed safe for swimming, it can become contaminated with debris and chemicals from roadways and golf courses during heavy rains. We often reminded August and Lyla not to play with bottles, cans, plastic bags, clothing, and other trash that sometimes litter the green space.

The abuse Onion Creek endures can sour its beauty. We often wondered about the future of Onion Creek, whether our kids’ kids would fish and swim in McKinney Falls State Park. An answer may come as the result of a case currently making its way through the Texas court system.

In 2015, the city of Dripping Springs applied for and received a wastewater permit allowing for the daily discharge of up to 882,500 gallons of treated sewage into Onion Creek. If utilized at maximum capacity, treated sewage could comprise 90% of the water in Onion Creek. When released into waterways, phosphorus and nitrogen within liquid waste dissolve oxygen levels. Fish and other aquatic life die. Stinky, gunky algae thrive. It’s not a family-friendly scene.

The wastewater would also threaten the water quality in the Barton Springs section of the Edwards Aquifer, which Onion Creek recharges. This led the environmental nonprofit, Save Our Springs Alliance, to sue the city of Dripping Springs, aiming to strike down the permit. Kelly Davis, an attorney who represented the SOS Alliance, argued the discharge of wastewater into Onion Creek violated the Federal Clean Water Act, a law created to protect pristine waterways. In 2020, a Texas District Court judge ruled in favor of the SOS Alliance, but Dripping Springs appealed.

“Will the city of Dripping Springs discharge effluent into Onion Creek?” I asked Bill Foulds, the mayor of Dripping Springs. “No,” he said, emphatically. Foulds explained the steps the city is taking to mitigate the need to use the discharge permit: an agreement with the Driftwood Golf Course to pipe as much as 1 million gallons of treated wastewater per day from Dripping Springs for irrigation use and the construction of at least two retention ponds to hold a minimum of 25 million gallons of treated wastewater. Foulds said the city intends to eventually treat its wastewater to drinking-quality standards, as other Texas cities have done. His sincerity echoed that of Dripping Springs residents, who he said were becoming more environmentally conscious.

“There’s an equity component to this, too,” Davis offered, referring to the low-income, predominantly Hispanic neighborhoods like Aguirre’s in southeast Austin along Onion Creek. “We don’t want to think that our more well-to-do Dripping Springs neighbors are fouling that water up. It’s like something from the 1800s, dumping sewage in the creek for those downstream to deal with.”

It’s possible this case could go to the Texas Supreme Court, Davis said. In 2021, the Texas House passed the “Pristine Streams” bill (HB 4146), which would limit discharge into streams such as Onion Creek. However, the bill was never assigned to the Senate.

The environmental uncertainty weighed on me as the pandemic waxed and waned, even as we visited Onion Creek less as life became more normal. Then, just after this past Christmas, I contracted COVID. The rest of the family tested negative. We followed CDC guidance, and I isolated in my bedroom, fully vaccinated. I had a stuffy nose, a sore throat, and a lot of FOMO. As I lay there in bed sulking, my phone pinged with pictures from my wife.

She and the kids were at Barkley Meadows Park, down in Onion Creek. Lyla, nearly 5, gave the camera a “Who, me?” look, her shoes and pants sopping wet. “Someone fell in,” my wife wrote. August, now 8, knelt beside a wall of creek stones. He was constructing a castle, complete with mortar.

I made the pictures full screen and pinched them to zoom in and scroll around. I started to feel a little better. Whatever this crazy world throws at us, I thought, we’ll always have our memories of life in the creek.

Peak Creek

Explore lesser-known waterways around the state.

Limpia Creek

Traveling from the slope of Mount Livermore at over 7,000 feet in elevation, Limpia Creek moves 63 miles through the Davis Mountains in West Texas.

Davis Mountains State Park, Fort Davis. 432-426-3337

White Rock Creek

Flowing 30 miles from the suburbs north of Dallas into White Rock Lake, much of White Rock Creek remains heavily wooded and home to abundant wildlife.

White Rock Lake, 8300 E. Lawther Drive, Dallas. 214-670-4100

Greens Bayou

A 28-mile paddling trail is in development for Greens Bayou, which stretches 42 miles from northwestern Harris County to Buffalo Bayou, east of downtown Houston.

Thomas Bell Foster Park, 12895 Greens Bayou St., Houston. 713-942-8500