By Clayton Maxwell

Texas and Louisiana find neutral ground along Toledo Bend Reservoir

Photographs by Kenny Braun

Winter cypresses and pines reflected in Toledo Bend Reservoir.

If you want to know Hemphill, the East Texas town Near Toledo Bend Reservoir on the Texas-Louisiana border, then you need to know Pennie Ferguson.

Her friends call her the Janis Joplin of Hemphill, and with her skein of red gray hair tied high, husky laugh, and quick wit, I can see why. A self-described “ninja,” Pennie leveraged her position on the board of the local hospital to bring better EMS services to Sabine County. She runs the Hemphill Daily News and More online newspaper and the Fishermen’s Village lodge where photographer Kenny Braun and I are staying. She’s also a volunteer firefighter. “I get so crazy, girl,” she says, “but I can’t stop.”

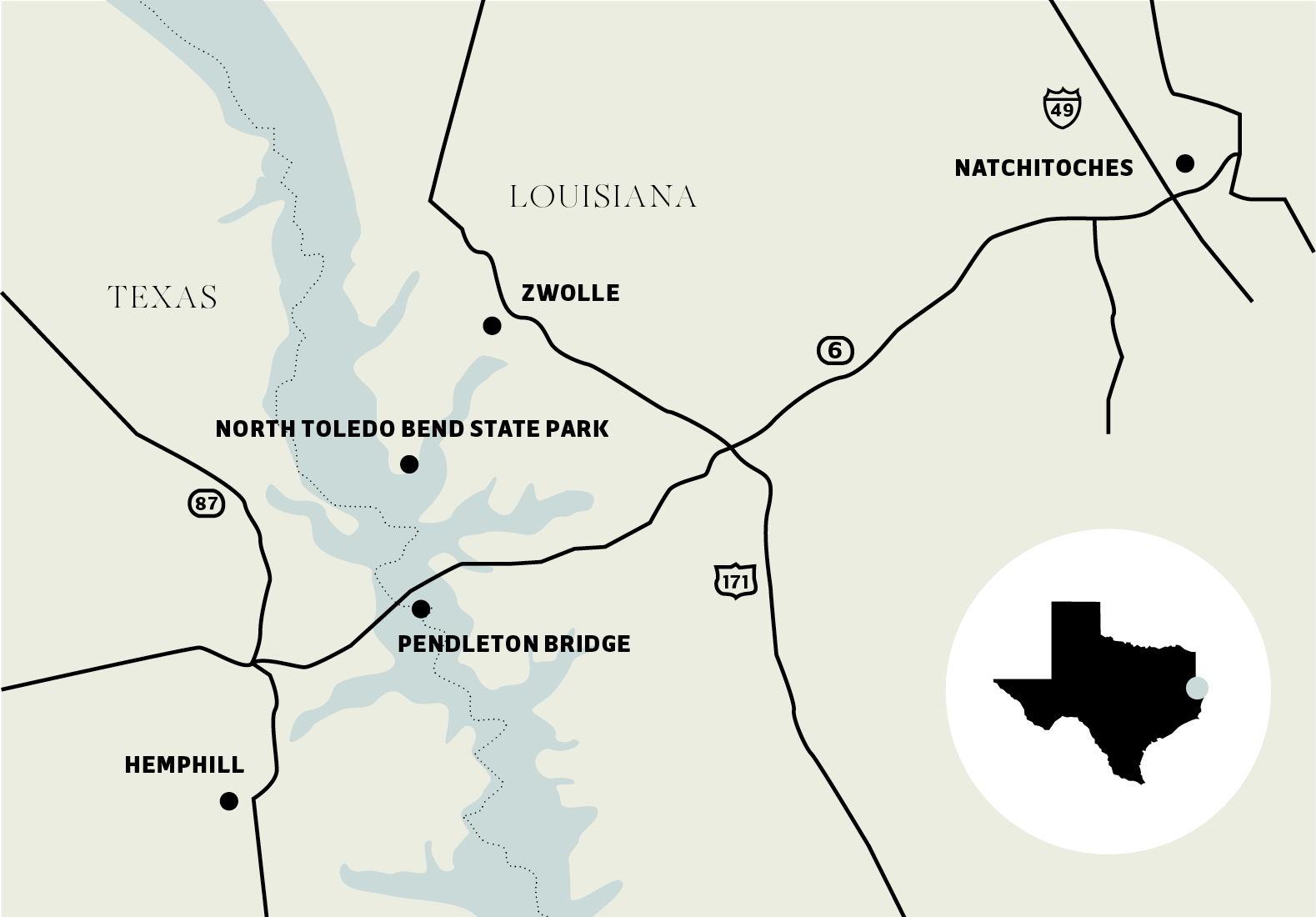

We meet Pennie in early February at her lodge about 2 miles from the Texas-Louisiana border on State Highway 21, the two-lane road that crosses into Louisiana and follows the ancient Camino Real, the roadway of the Spaniards in the 1700s and the Caddo people before that. Within minutes, Pennie loads us into her truck for a drive over to Louisiana on the Pendleton Bridge, a narrow concrete engineering feat built in the late 1960s when the Sabine River Authority dammed the river and gave birth to this mammoth lake. With overcast skies above, the water today is a flat gray expanse stretching endlessly north and south. We pass a small green highway sign just off the Texas shore that simply says “Sabine River,’’ a reminder that the river channel is still there, invisible to us now.

Kenny and I are exploring Toledo Bend, a fishing mecca that stretches 65 miles between Texas and Louisiana, to see what kind of border a lake makes. Although it’s the largest body of water in Texas and consistently yields prize-winning bass, I only just discovered it because I heard some Louisianan folks touting its charms on a recent trip to New Orleans. Toledo Bend is relatively unknown to many Texans, particularly those unfamiliar with the eastern edge of the state. Back in 1806, after the Louisiana Purchase, Spain and the United States couldn’t agree on exactly where their border here should be, so they declared the area east of the Sabine a “neutral ground.” It was an in-between space where people weren’t necessarily from one side or the other, where cultures collided and mixed like a jambalaya. I’ve set out to discover what the region is like now, 50 years after the creation of the 289-square-mile lake turned the area into a recreational destination.

Looking out from the Pendleton Bridge, I imagine what else that water is covering. Weldon McDaniel, president of the Sabine County Historical Commission, would later tell me that on the north side of the bridge, now submerged, stand the remains of the old Pendleton Gaines Bridge that crossed the river from 1937 to 1967. That quaint truss bridge took the place of the even quainter Old Gaines Ferry, a crossing operated as far back as 1794. The ferry served as a major port of entry to the Republic of Texas in the 1800s when it carried many of the state’s settlers, allegedly including Stephen F. Austin. From a historic ferry to a truss bridge to the 2.4-mile viaduct we are driving now, the evolution of this Sabine crossing is a dense microcosm of Texas history and modernization.

As soon as Pennie drives us to the other side of the bridge, it’s clear we’re not in Texas anymore. Banners splashed with the gold, green, and purple colors of Mardi Gras festoon the roadway, and a tourist center flies the Louisiana state flag—sky blue with a white pelican. A 6-foot sculpture of a writhing bass painted by local artists reminds us that whatever side we’re on, we’re in bass country. And to put us in a festive state of mind, a tackle shop and convenience store just up the road sells drive-thru daiquiris.

Opting to skip the daiquiri in favor of a Texas margarita, Pennie scoots us back across the bridge for dinner with her friends at Lost Frontier—a marina and restaurant full of taxidermy, fried food, and fishermen. There we meet Stephen Stubbe, aka Captain Scooby, an Orvis-endorsed fly-fishing guide and retired engineer who promises to take Kenny and me on a “mudfishing” trip once the sun comes out. With sparkly eyes and a mustache, Captain Scooby is part Captain Kangaroo, part mad scientist of fishing. He tweaks old techniques to find new ways to fish, crafting flashy 8- to 12-inch flies with tinsel and fur to lure bass out of cypress roots in Toledo Bend’s shadowy backwaters. Scooby also commissioned himself a customized boat with GatorTail boat manufacturers. Rigged with a motor that’s part lawn mower, its essential superpower is popping over the ubiquitous stumps and fallen logs that have stranded many a vessel on the Sabine River and Toledo Bend. Hence, Scooby can go “shallowing” where high-end bass boats cannot.

Over “alligator kickers”—spicy fried and battered alligator bites—Pennie, Captain Scooby, and crew regale us with the mysteries of Toledo Bend; we might bump into a Bigfoot, or even the Loch Ness Monster. We discuss arcane variations between alligator hunting in Texas and Louisiana. It’s legal with a license in both states, but there are endless technicalities in how to go about it. Numeric differences between Texas and Louisiana come up often in our four-day tour of this borderland. Gas tends to be cheaper in Texas, but fishing licenses cost more. Weldon’s wife, Beth McDaniel, says her grandparents drove from Texas across state lines to marry because her grandmother was only 14, the legal marrying age in Louisiana at the time. I ask Pennie if she goes over to Louisiana much. “Don’t be silly,” she jokes. “I wouldn’t mingle with those people unless I needed a daiquiri.”

Pennie’s quips aside, people here mingle plenty across state lines. Pennie is part of the Lasyone family from outside of Natchitoches (pronounced Nack-Uh-Tush), the oldest settlement in the Louisiana Purchase and about an hour’s drive from Pendleton Bridge. In 1967, the Lasyones opened an eponymous Cajun restaurant famous for its empanada-like meat pies. On a day where I’m wearing two pairs of socks to keep my toes from freezing, hot meat pies seem worthy of a pilgrimage.

So we leave the pine curtain of East Texas and follow the Camino Real—State Highway 6 on the Louisiana side, a two-lane road that cruises past rural homes shaded by scattered pines. One of those numeric state differences Pennie did not mention is the speed limit: On the other side of the border, it drops down to 55 mph. It feels as slow as strolling in a Mardi Gras parade. But, what’s my big hurry? Natchitoches has been there since 1714; it’s not going anywhere.

Besides, when I go too fast I’m likely to miss things, like the sign for the Los Adaes State Historic Site just outside of Robeline. It’s closed today, so I drive right past an underappreciated hot spot of Texas history. During the French-Spanish tug of war for this terrain in the 1700s, Spaniards built Los Adaes as a fort around 1720 and soon thereafter named it the capital of the Spanish province of Tejas, which it remained until 1772. Consider that: Thanks to the vagaries of border-making, the first capital of Texas ended up in Louisiana.

We arrive at Natchitoches’ historic Front Street overlooking the Cane River, a tributary of the Red River, and I’m instantly charmed. We’ve landed upon a mini French Quarter, with wrought-iron balconies atop blues bars and restaurants. Lasyone’s, an unpretentious diner, is even more endearing than Natchitoches’ red brick streets. The real gold here is the staff, like Travis Newton, a congenial manager who pops out of the kitchen for a little Drew Brees versus Tom Brady quarterback smack talk with me, a reminder that when you cross into Louisiana, you also cross into Saints Nation. Equally affable is our waitress Helen Winn, who is proud of Lasyone’s global fame. “People come here from France,” she says. “They’ve heard about our meat pies clear over there.” As I bite into the fried pastry containing a savory mix of ground beef, pork, onion, celery, and bell peppers, I can taste why.

On our way back to Texas, we stop in Zwolle, a town about 15 miles from the border with an improbable number of tamale makers. Perhaps even less probable is that the town’s name rhymes with the food for which it is known. We pull up at L&W Tamale House, a white house with smiling frog statues in the yard, and order a dozen tamales to go. L&W’s owner, Linnie Sepulvado, her fingernails painted gold for Mardi Gras, meets us at the tamale pickup window. She is the “L” in the name. Her husband, Wayne Sepulvado, is the “W.”

“Ever since I came up out in the country, we was always making tamales in the old black pot at home,” she says. “When we moved over here I just kept on making them. All the country people around here make them. It’s not Mexican. This is more Indian and Spanish over here. Apache and Choctaw.” Marveling at the cultural forces that collided to bring about this hot bag of tamales in my hand, I unwrap one from its corn husk and bite into the fresh and tender masa.

A cabin in North Toledo Bend State Park

Back in Texas, we try to pop in to Hemphill’s Patricia Huffman Smith NASA Museum, a tribute to the Columbia Space Shuttle and its fatal disintegration across Sabine County in 2003. But this visit would be more than a pit stop; the stories told here are so gripping, I leave an hour-plus later with tear-smeared mascara. The museum’s documentary, Of Good Courage, relates how the people of Hemphill aided the NASA and FBI recovery teams who came to town to search for the shuttle’s scattered remains. Bethany Dorsey, the bright-faced museum docent who wasn’t yet born when the Columbia fell, ably shares details of the tragedy. One tidbit: Mission Control played “Fake Plastic Trees” by Radiohead as the astronauts’ morning wake-up call because it was a favorite of Willie McCool, the Columbia pilot from Lubbock.

Next, we are treated to some unexpected sorcery courtesy of Weldon, whose history center office is lined with tidy binders featuring titles such as “Sabine River Authority Photographs of Black African American Farms in the Robertson Bend, Book One.” A local cemetery expert, Weldon is dedicated to helping people find their ancestors, particularly those of African American descent. He employs a witching stick to determine if a buried body is male or female. He shows us, with jaw-dropping accuracy, how his witching stick works. Holding the bent stick in front of him, Weldon walks toward me, and as he gets close, the stick makes a sharp turn to his left. When he walks toward Kenny, the stick takes a far right. Is he pulling our legs? We check his methods and deem it impossible that Weldon is manipulating the stick. Amused by our stunned faces, Beth says, “Now, that’s some New Orleans voodoo right there.”

Hook, Line, and Sinker

Mudfish Adventures with Captain Scooby

Take a curated fishing or nature tour with the fly-fishing wizard of Toledo Bend.

2960 Palo Gaucho Xing, Hemphill.

844-683-3474; mudfishadventures.com

Lost Frontier RV PARK and Marina

With cabins, RV spots, lake access, and a restaurant, this is a mainstay of Toledo Bend fishing culture.

360 Frontier Drive, Hemphill.

409-404-9972; lostfrontierrvpark.com

Lasyone’s Meat Pie Restaurant

This laidback eatery serves authentic home cooking in the heart of the Natchitoches historic district.

622 Second St., Natchitoches, Louisiana.

318-352-3353; lasyones.com

L&W Tamale House

The tamales served through L&W’s take-out window are as fresh and flavorful as it gets.

1547 Oak St., Zwolle, Louisiana.

318-645-6407; facebook.com

Fisherman’s Village Lodge

The house accommodates fishermen and lake lovers; sleeps 12. Rooms start at $125 for two guests.

5518 State Highway 21 East, Hemphill.

409-787-3138; fishermansvillage.us/lodge.asp

Toledo Bend North State Park

The fishing-centric state park offers boat access and comfortable cabins starting at $150.

2907 N. Toledo Park Road, Zwolle, Louisiana.

318-645-4715; lastateparks.com/parks-preserves/north-toledo-bend-state-park

The next day the sun comes out, and it’s time to get out on the water. We meet Captain Scooby on the shore of the cypress-lined Toledo Bend feeder creek that is his backyard. The lake that had been dull gray on our arrival is now translucent blue and shimmering, as if someone had turned on a disco ball. It’s not unlike being around Scooby. He is so in love with fly-fishing and his corner of Toledo Bend that his boyish enthusiasm radiates, catching us in its shine.

For my first casting lesson, he shows me how to press my thumb on a Scooby-designed women’s fly rod—crafting lightweight fly rods for women is one of his innovations. I angle the rod back and forth overhead from 11 to 1 o’clock, my line tracing a serpentine trail against the blue sky. Scooby has Kenny pull on the end of my line, emulating the tug of a big fish. I am giddy before we even get in the boat.

After backing his custom rig into the water with a joyful shout, Scooby zips us across the lake to those stump-strewn sloughs where other boats can’t go. It’s an exquisite freedom, to glide through the mazes of marsh grass and moss-cloaked cypress while Scooby points out things I would never notice, like the slide marks in the mud where snapping turtles crawl in and out of the water. With reverent glee, he shows us all the hollows where big bass lurk. The water is so glassy in the descending light, it’s hard to tell where the reflections of the cypress trees end and the real things begin.

As if we are on safari, Scooby is quiet and alert, his eyes scanning the water and skies around us. He’s good at explaining the complex relationships between species and elements out here. “You have to pay attention to everything,” he says. “If it’s too muddy you can’t catch fish because they can’t breathe in it. If there is an eagle in the air, he’s looking at fish, so I’m watching him. I go into an area and there’s an alligator, I know there’s a big group of fish there.”

We practice casting in a quag spacious enough for a couple of beginners who can’t yet control where they fling flies. Captain Scooby points to a reed sticking out of the water and tells us to aim for that. I want to be good so badly, I cast too fast. The gap between my aspiration and execution looms large. Scooby tells me to ease up, to say out loud “Toe-Leeeeee-Doooooo-Beeeeend” and slow my movements to the rhythm of the words. With his guidance, I find my groove. Spoiler alert: Kenny and I don’t catch a fish; it’s a cold day in February. This is just casting practice.

But I don’t care. Scooby’s fly-fishing brio is so contagious, I get a vicarious high from it, even though there’s no fish on my line. With the sun going down, we motor to the spot where the cormorants perform their sunset ritual, flying graceful Vs against the rosy sky. Watching the show, we are quiet. “Can’t you hear yourself think?” Scooby says, eyes sparkling. I wonder why it took me so long to find this place.

The next morning at sunrise, Kenny and I hike through the woods by our cabins in the North Toledo Bend State Park near Zwolle. As sunbeams first hit the loblollies, the ruckus of thumping woodpeckers and calling crows make the silent anglers gliding by on their bass boats seem like serene monks. A loud screeching noise, which I first took for a wild hog, turns out to be the protective cry of a glorious bald eagle perched by her nest. She locks eyes with me, asking what I’m doing in her woods. My heart leaps.

There is much more here than I had realized: the nature in these woods and Toledo Bend’s backwaters; smart characters like Pennie and Weldon who are passionate about Hemphill and its history; the warm crew at Lasyone’s and L&W infusing the border with their distinctive flavors. I am humbled by all that I’d missed on previous trips. The area may no longer be called ”neutral ground,” but this border lake retains a friendly stew of culture and people, no matter which side you’re standing on.

What Went Under

On the south side of the bridge near Texas lie about 70 graves the Sabine River Authority did not disinter before the dam flooded them. Weldon McDaniel, a retired school teacher and historian who grew up in the ’40s in the Sabine River bottomlands, devotes himself to chronicling all that was lost when the Sabine was dammed. He created a Facebook page titled “What Went Under” that posts the homes, churches, and cemeteries that disappeared and the people who lived among them. The group became so popular that Weldon helped organize “What Went Under” live gatherings. Four to five hundred people from both sides of the Sabine came together to honor what was lost. “It’s really neat to get all these people together,” he says. “They bring all their pictures, and everybody reminisces.” The next event is tentatively planned for spring 2023. facebook.com/groups/1502194386501422