Pressed for Posterity

Texas herbaria preserve botanical specimens for scientific research and natural wonder

Not far

from where

Mexican

wolves lounge

among the boulders and shrubs in their enclosure at the El Paso Zoo, young children lean over a table, carefully examining plant specimens and dried seeds. They take turns using plastic magnifying glasses and trace their fingers over the globe mallow and desert unicorn plants, pondering the shapes and functions of their stems and leaves. Even amid the excitement of the surroundings, the novel sight of plants that have been dried, pressed, and preserved on sheets of paper captures the kids’ curiosity. That’s the goal of the University of Texas at El Paso’s Biodiversity Collections, which organized the display of its herbarium specimens for Chihuahuan Desert Fiesta, an annual event held in September.

“Plants can sink into the background because we see them every single day—we just walk right past them,” says Vicky Zhuang, manager of the Biodiversity Collections. “But they’re really cool, and the more people learn about plants, the more they start noticing them.”

Educational outreach is a key function of the UTEP Herbarium, which is one of 34 active herbaria across Texas, mostly located at publicly accessible universities and botanical gardens. As caretakers of preserved plants collected by generations of naturalists, the herbaria chronicle the botanical history of Texas and beyond. The institutions harbor millions of specimens that, sheet by sheet, provide a tangible snapshot of the time and place the plants were collected. Beautiful and delicate, the specimens serve as resources for scientists working on botanical research as well as inspiration for artists and gardeners.

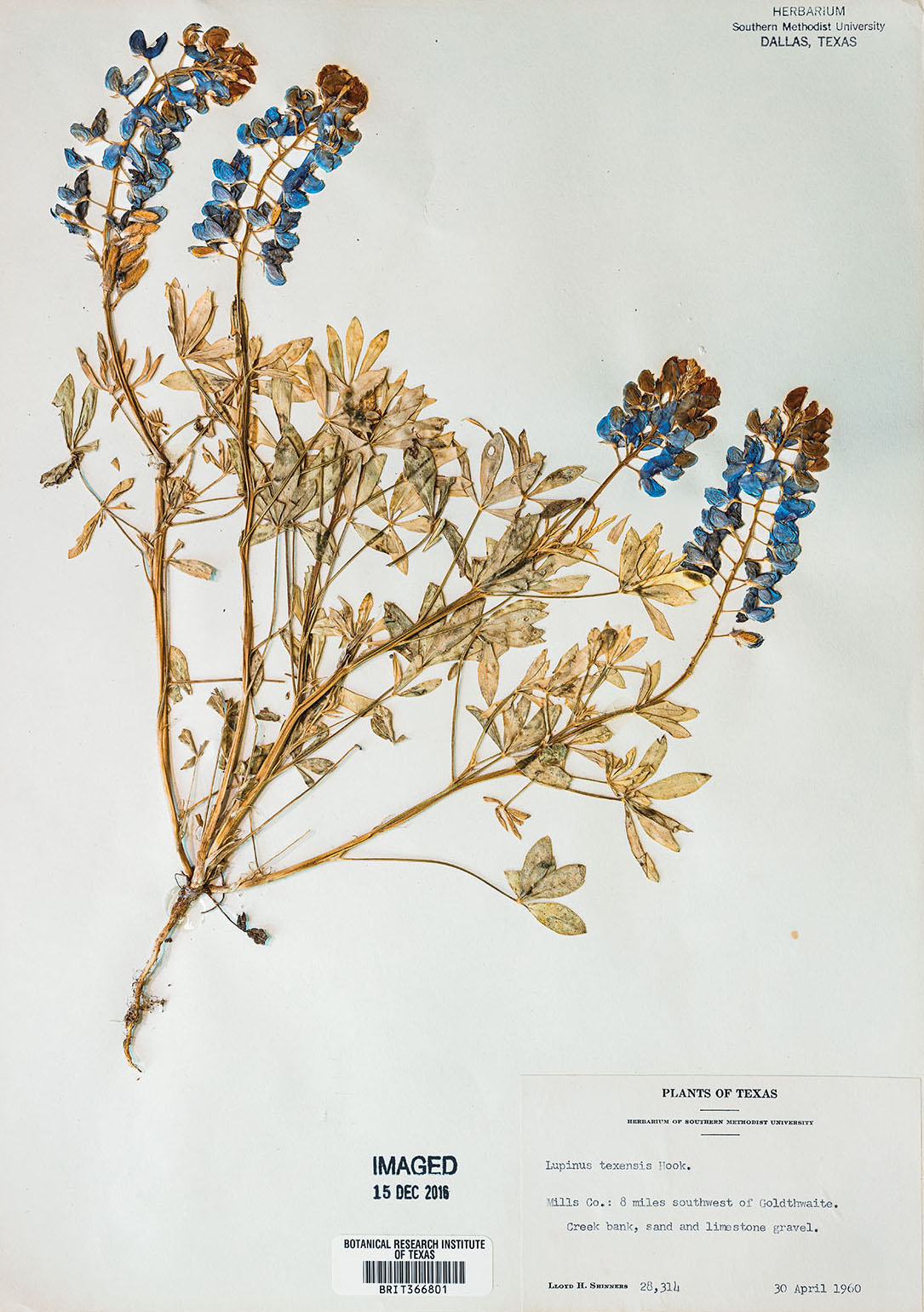

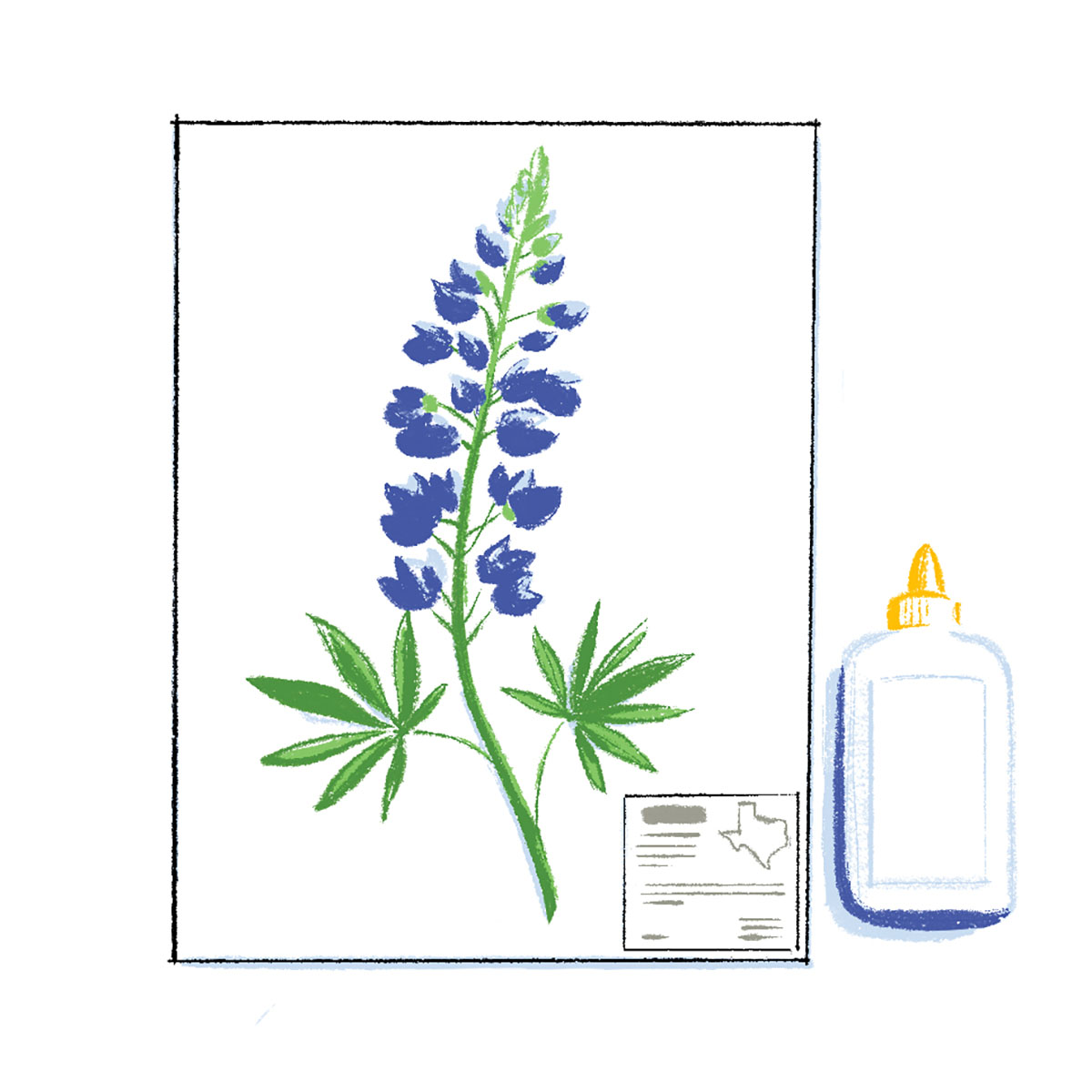

Opening image: Flowering dogwood, Mercer Botanic Gardens. Above: Texas bluebonnet, BRIT

“The herbarium collections are intrinsic to our work, whether we’re studying ecosystems to figure out where plants have existed over time, or whether in taxonomy and identifying new species,” says Michael L. Moody, director of the UTEP Herbarium. “Each regional herbarium is important because we all hold different types of specimens.”

In addition to their scientific value, the pressed plants are striking to behold. The dried stems, leaves, and petals evoke a natural connection to the past, not unlike a sepia-toned photo or a family heirloom Bible. The centuries-old practice of plant pressing is experiencing a renaissance in the decorative arts. There are how-to guides for backyard collectors and a range of boutique businesses that preserve plants as keepsakes from special occasions like weddings. Last August, The New York Times published a visually rich story on the trend. And on a recent episode of the TV show Fixer Upper, Joanna and Chip Gaines debuted the herbarium they built on their property in Waco. Considering the mainstream interest, some herbaria offer workshops on plant pressing for crafters and naturalists alike.

“With fairly low skill and low tech, you can press plants and they’ll keep their aesthetic value, potentially forever,” says Brooke Byerley Best, director of Texas plant conservation at the Botanical Research Institute of Texas at the Fort Worth Botanic Garden. “Capturing that moment in time has a pull for humans.”

Historians credit the Italian botanist Luca Ghini with developing the first herbarium—he called it a hortus siccus, or dry garden—in the 1500s. Ghini taught medicine, which at the time utilized mostly plant-based remedies. He pressed plants in the pages of books to preserve them to use for winter lessons when his garden was dormant. In the 19th century, naturalists such as Thomas Drummond from Scotland and Ferdinand Jacob Lindheimer from Germany scoured the Texas countryside to discover previously unknown plants, sending the bulk of their collections to herbaria in eastern U.S. cities and Europe for scientific study.

In 2019, the National Science Foundation awarded a $1.5 million grant to help about 50 members of the Texas Oklahoma Regional Consortium of Herbaria, which includes the Fort Worth Botanic Garden, digitize their collections of regional plants. This involves photographing them and placing the images and label information online, explains Tiana Rehman, director of Fort Worth Botanic Garden’s herbarium. The searchable database of images is online at torcherbaria.org.

Many plant species reach their eastern or western limits in Texas and Oklahoma, Rehman notes, which makes them important indicators of plant distribution, or where different species have grown over time. “These specimens represent data points for us to ask questions about biodiversity and climate change,” she says. “But they’re stored in cabinets around the country. The point of the digitization project is to make the data accessible for researchers. The number of questions you can ask with the data we’re putting online is infinite.”

The digitization of herbaria collections expands their utility, but it doesn’t dilute the value of the physical pressings. A specimen serves as proof of a species’ existence at a specific time and place. And as technology evolves, scientists are finding new ways to use the specimens. For example, they can take tiny clippings from the dried plants to study their DNA and identify new species; and they can use scanning tools on three-dimensional plant parts that would be impossible with a digital image. “We’ve actually seen an increase in physical loan requests now that people can see these specimens online,” Zhuang says.

Here we visit three herbaria—in El Paso, Fort Worth, and the Houston area—that represent the state’s botanical diversity.

A BRIT employee tightens straps on a wooden plant press

Glandularia bipinnatifida Prairie verbena

Lindheimer House

Known as the “father of Texas botany,” Ferdinand Jacob Lindheimer was a pioneering chronicler of the state’s flora and a founder of New Braunfels. There, the 1852 Lindheimer House preserves his legacy with 19th century plant specimens, historical furnishings, and a garden bursting with native plants. Born in Germany in 1801, Lindheimer moved to the United States in 1834 to escape political persecution. After settling in Texas in 1836, he supported himself by sending pressings of plants to repositories on commission. He scoured the eastern and central parts of the young republic, ultimately shipping over 2,000 specimens to Harvard University and 1,400 specimens to Missouri-based botanist George Engelmann, who named the cactus Opuntia lindheimeri, or Texas prickly pear, for him. In 1964, Lindheimer’s granddaughter donated the historic family home to the New Braunfels Conservation Society, which restored it and opened it as a museum. With its two front doors, outdoor bathroom, and traditional fachwerk construction, the home is a relic of the city’s German origins. 491 Comal Ave., New Braunfels. Tours available by appointment. 830-629-2943; newbraunfelsconservation.org/lindheimer-house

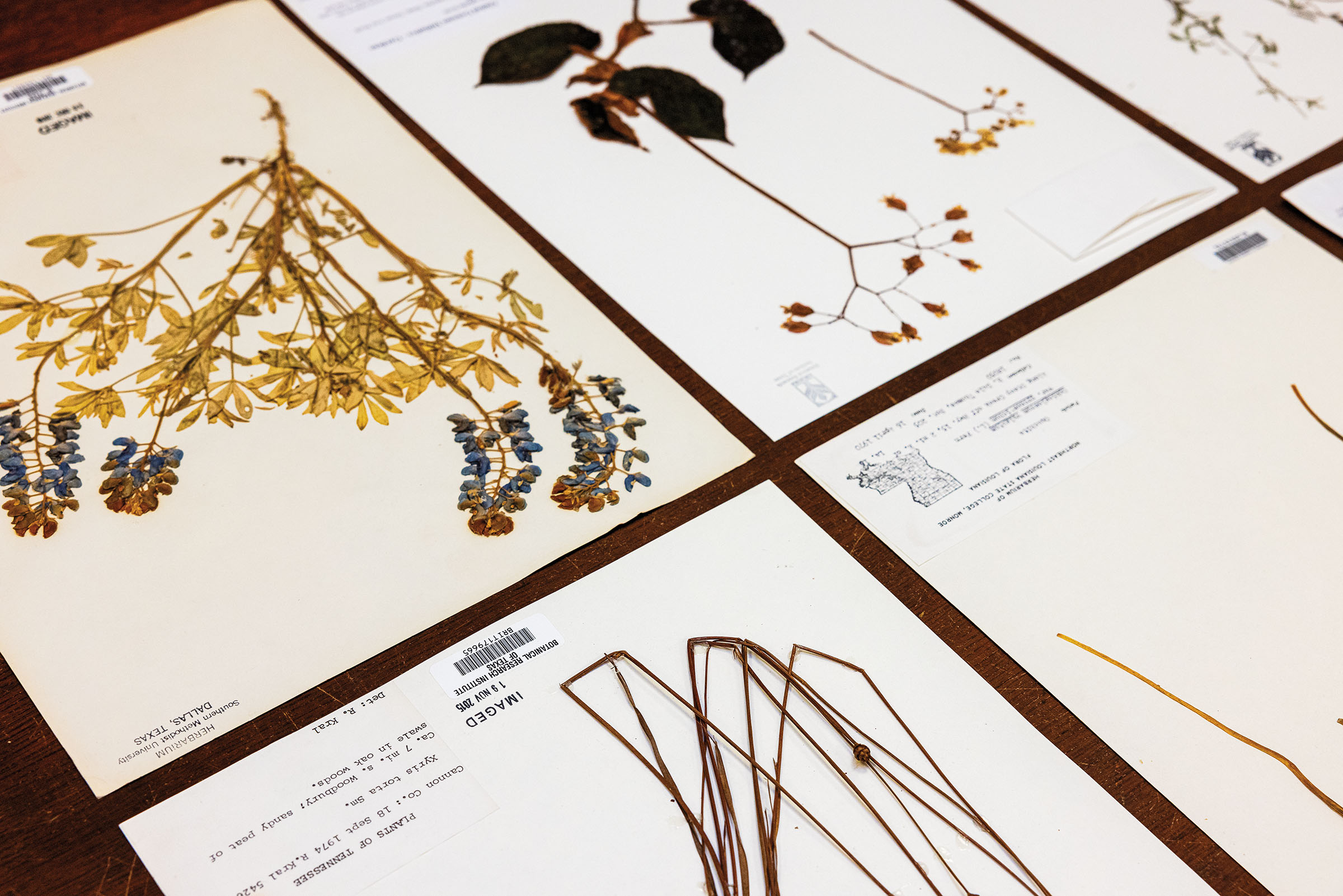

BRIT volunteers mount pressed plants

Pressed plant specimens

Botanical Research Institute of Texas

On any given day, visitors to the Fort Worth Botanic Garden will find volunteers gathered around a table at the Botanical Research Institute of Texas, or BRIT, mounting pressed plants. They pluck hundreds of clippings from boxes arriving from as far away as China and Brazil and attach them to sheets of paper. The surrounding botanic gardens offer a manicured visual bounty, while BRIT provides a scientific complement with its molecular lab, digitization studio, seed bank, botanical library, and Philecology Herbarium. The latter holds 1.4 million specimens, making it Texas’ largest.

“Our primary role is to preserve these plants and make them accessible for scientists who are studying a particular group of plants,” Rehman says. “The importance of these herbaria is ultimately as a reference resource of primary data about the biodiversity of the world.”

BRIT formed in 1987 to adopt SMU’s Philecology Herbarium and has since added to its inventory large collections from Vanderbilt University, the University of Louisiana Monroe, and elsewhere. In addition to Texas, BRIT’s collection spans the southern United States and biodiversity hot spots across all seven continents. It acquires more than 5,000 specimens per year.

To protect the collection, BRIT staffers send all incoming plants through a processing room. Freshly collected plants are placed in a large dryer to desiccate them and prevent rot. Then they’re moved to a freezer to kill off any pests, such as the “herbarium beetle,” which chews on leaves and discards larval cases. “Even if a specimen leaves the herbarium and is taken off-site to somewhere like a school, it’s still required to come back through the freezer,” Rehman explains.

Fouquieria splendens Ocotillo

A two-story wall of windows that opens to a view of a restored prairie greets visitors and casts natural light across wall exhibits with information on botany, plant uses, and conservation methods. But it’s the scientific record contained in the herbarium specimens themselves, filed away in large rolling stack shelving, that underscores BRIT’s mission. The herbarium preserves numerous specimens that are historically significant because of their age and connection with pioneering naturalists. This includes a milkpea collected by Lindheimer in Texas in 1847; a bushy heliotrope collected by Czech botanist Thaddaeus Haenke in Mexico in 1791; and ferns collected by John Muir in California in 1875.

Another key part of BRIT’s preservation effort is its seed bank, a repository for replenishing plants in case of catastrophe. So far, its freezer holds the live seeds of 40 rare and threatened Texas native plants, such as white rosinweed, found in open prairies; and large-fruited sand verbena from Freestone County. For each species, the bank keeps seeds from 50 different plants to capture genetic diversity. “It’s a little bit like Noah’s Ark,” Best says. “Seed banks are safeguarding against loss like extinction or destruction from wildfires. We will have seeds here to restart or restore populations.”

BRIT’s library is also a trove of rare finds, including copies of Curtis’s Botanical Magazine, the world’s longest-running botanical journal. The 1836 edition contains the first scientific description of Lupinus texensis, based on Drummond’s discovery of a Texas bluebonnet in 1834.

Cataloging specimens for BRIT

Botanist and herbarium curator Anita Tiller surveys the Mercer Botanic Gardens.

The Art of Being a Wallflower

Backyard botanists. Bridal parties. Arts-and-crafters. People collect and press their plants for reasons that range from scientific observation to creating beautiful keepsakes. Here are some tips for how to get started.

Collecting

Parks typically require permits to remove plants. Take care not to displace rare plants. “Make sure you have permission, and keep conservation in mind,” says Tiana Rehman, herbarium director at the Fort Worth Botanic Garden.

Photograph a plant before you remove it to assist with identification—the iNaturalist app can be useful. Document the collector, date, location, and surrounding habitat. When digging up a plant, include the roots and bulbs. Collect plants when they’re flowering or fruiting for visual appeal.

Pressing

To create a plant press, layer absorbent material, such as paper towels or folded newspapers, on top of a piece of cardboard. Place the clipped plant between either paper, arranging it carefully to show all parts of the plant including both sides of a flower or leaf. Sandwich the plant between the absorbent paper and cardboard layers using a plant press or heavy books.

The plant needs to be dry, so check it regularly and replace any wet absorbent paper. Herbaria use special dryers to dehumidify their plants, but at home you can place your press in a hot and dry space or in front of a fan. “Some people actually leave their press in the trunk of their car in the summer, as the heat speeds up the drying process,” says Anita Tiller, botanist at Mercer Botanic Gardens.

After the plants are pressed, place the specimens in the freezer to kill any lingering pests.

Mounting

Use heavy cardstock paper to mount the pressed and dried plant. In a herbarium, a label card is placed in the lower right-hand corner of the paper.

Position the plant on the paper to show all its parts. Then outline the back of the plant with a minimal stream of glue and gently press it down against the paper, blotting away any extra glue. Elmer’s glue works fine.

For detailed tips, including information on preservation and storage, check out the Fort Worth Botanic Garden’s how-to page: fwbg.org/category/phytophilia-blog/plant-collecting-how-to

Illustrations by Arthur Mount

Mercer Botanic Gardens

On the banks of Cypress Creek, a tributary of the San Jacinto River that forms the border of Humble and Spring just north of Houston, the herbarium at Mercer Botanic Gardens occupies the second floor of a two-story building. The upstairs placement would seem inconvenient—all that up and down—but the decision was no accident. In early 2017, when the herbarium’s collection grew tenfold with the long-term loan of about 40 cabinets’ worth of pressed plants from the R.A. Vines Spring Branch Environmental Science Center, Mercer botanist and herbarium curator Anita Tiller insisted the newly expanded collection be placed upstairs.

“Even though it was difficult to move the cabinets to the second floor, I didn’t want to risk placing them on the ground floor considering the flood risk,” Tiller says.

A few months later, in August 2017, Hurricane Harvey submerged much of Mercer in 10 feet of water, causing extensive damage to its gardens and buildings. Eight inches flooded the herbarium’s building, but the delicate pressed plants “were upstairs safe and sound and had no damage to them,” Tiller says.

The herbarium’s survival contributes to the Mercer Botanic Gardens’ commitment to conserving and restoring native plants of the Gulf Coast’s prairies and forests. In partnership with the Center for Plant Conservation, a nonprofit dedicated to saving rare plant species from extinction, Mercer is charged with caring for 28 threatened or endangered species.’

Mercer’s gardens—fully recovered from Harvey—bloom with colorful plants from around the world. The Endangered Species and Native Plant Garden focuses on common and threatened plants of the Gulf Coastal Plains. Visitors can see rarities such as the Houston camphor daisy, found only in Houston-area prairies; Texas windmill grass, found only in the coastal prairies of Texas; and Texas trailing phlox, found only in the Big Thicket. Shaded by towering loblolly and longleaf pines, the garden is a refuge for plants threatened by habitat destruction, invasive species, and overcollection.

Mentzelia multiflora Adonis blazingstar

The herbarium’s collection of an estimated 52,000 specimens includes “vouchers,” or proof specimens, for the 28 threatened species. The Botanical Center’s nursery maintains the plants, while its seed bank stores their seeds. Recent scientists who have visited the herbarium for research include a Rice University student who took tiny clippings of some of the herbarium’s grass specimens to aid in his study of fungi that live within grasses.

“You don’t want to overcollect rare specimens in the wild,” Tiller says. “People who want to study these plants can examine the plants in the garden and nursery and study our herbarium specimens.”

Mercer offers tours of the herbarium, which has species from around the world along with regional specimens that date to the 1930s. There is also a botanical reference library and an art collection of works inspired by pressed plants. With Houston expanding its footprint as the nation’s fifth-most-populous metro, the Mercer herbarium grows in importance as a repository of the natural history of the Gulf Coast environment.

“We want people to understand how fascinating herbaria are,” Tiller says. “They’re treasures that document the history of a location based on the plants.”

A sheet of candy barrel cactus from the UTEP Herbarium

UTEP Herbarium

UTEP sophomore Christopher Nowakowski, an ecology and evolutionary biology major, discovered the UTEP Herbarium through a call for volunteers. While working to label plants and organize new cabinets, Nowakowski started venturing into the nearby mountains to find where the herbarium’s specimens were collected decades ago. He’s explored the Franklin Mountains of El Paso and ranges in New Mexico and Arizona.

“I really like to see the plants in their habitats,” Nowakowski explains. “I’ll put the label’s coordinates into my phone, and I’ll try to find them and get photos of the plants in their natural habitat to share online.”

With 90,000 specimens, the UTEP Herbarium is a prime source for botanical researchers interested in the vegetation of the Chihuahuan Desert and Southwestern U.S. The herbarium opened in 1965 and traces its roots to the late Elsie Slater, who preserved plant clippings in El Paso in the 1920s and ’30s. Slater’s specimens, including American star thistle and spotted beebalm, provide historical perspective on the flora of El Paso’s urbanized landscape.

The UTEP Herbarium also serves as an educational and outreach hub for the university. “The specimens get used for teaching a lot,” says herbarium director Moody, an associate professor of biological sciences. “I use them in all of my classes for botanical studies.”

Across campus, the Centennial Museum supports the herbarium with natural history exhibits that interpret El Paso geology and wildlife. Surrounding the museum, the Chihuahuan Desert Gardens harbor dozens of local plants, from alligator juniper trees to mealycup blue sage to goat’s horn cactus.

Zhuang organizes off-campus displays for events like Chihuahuan Desert Fiesta. UTEP students work the display tables, giving them an opportunity to talk science with the public. One favorite example is the devil’s claw seed pod, which has spindly fingers that can jab passing animals, distributing the plant’s seeds.

“We bring the specimens with us to educate people not only about the natural history of the region, but also about why collecting is important and the purpose of natural history collections,” Zhuang says.

A participant at the Chihuahuan Desert Fiesta

Head to the Herbaria

Botanical Research Institute of Texas, located in the Fort Worth Botanic Garden, displays plant specimens and artworks inspired by the herbarium collection. Philecology Herbarium tours are offered by appointment.

3220 Botanic Garden Blvd., Fort Worth.

817-332-4441;

fwbg.org/research/herbarium

Mercer Botanic Gardens is open daily except for Thanksgiving, Christmas Eve, Christmas, and New Year’s Day. Tours of the herbarium, which includes a botanical reference library and an art collection, are offered by appointment. Free admission.

22306 Aldine Westfield Road, Humble.

713-274-4160;

pct3.com/mbg

UTEP Herbarium, located in the Biodiversity Collections at UTEP, offers tours based on staff availability. Herbarium specimens are on display in April at the El Paso Zoo’s Eggstravaganzoo and at UTEP Centennial Museum’s Florafest Native Plant Sale in October.

500 W. University Ave., El Paso.

915-747-5479; utep.edu/biodiversity