Locked Up

Museums in historic jail buildings display the history of Texas crime and punishment

By Robyn Ross

Old county jails stand as imposing reminders of nascent frontier justice across the state. Although the first facilities were primitive—tiny one- or two-cell “calabooses” made of metal, concrete, or wood—they improved on the existing practice of chaining people accused of crimes to a pole or tree. In the latter half of the 19th century, the primitive structures were replaced by brick or stone buildings whose fortress-like appearances conveyed authority in an era of lawlessness.

The first floor of most jails housed an apartment for the sheriff and his family. Above them were low- and high-security cells and, often, a separate cell for women, juveniles, and “lunatics”—the era’s term for people who were mentally ill, publicly intoxicated, or had seizure disorders. Several historical county jail buildings were used for close to 100 years; the 1890s Mason County Jail is still in service. Many of the old buildings have been converted into museums where visitors can learn about their somber histories.

Upstairs, Downstairs

Sandra Wolff, director of the Gonzales County Jail Museum, spent a decade of her childhood in the 1885 jail—on the first floor, that is, during part of her father’s term as sheriff. In the 1950s and ’60s, the jail held only people serving time for minor crimes, such as theft and public intoxication. Wolff’s mother cooked two meals a day for the men held upstairs, a common practice for sheriffs’ wives. By the time Wolff turned 16, living at the jail had lost its intrigue. The old building was hot in summer and cold in winter, and her mother was tired of cooking. Plus, socializing with her peers was difficult. “People don’t come see you when you live in jail,” Wolff says. The family moved into a house for the rest of her father’s term. 414 St. Lawrence St., Gonzales. 830-263-4663

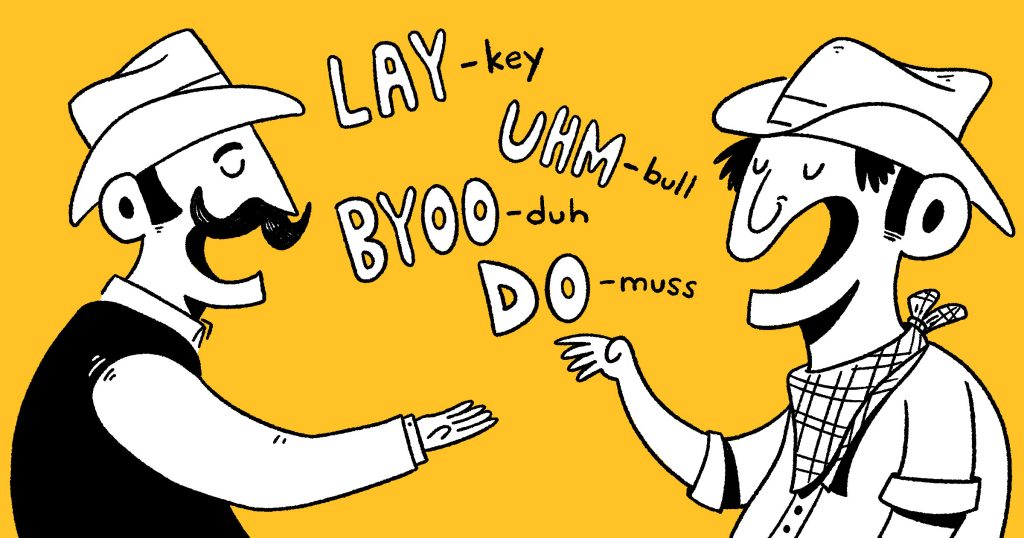

Priors

Since the state’s jails first opened, violent crimes and theft could land a person in the county jail, but so could a host of actions that are no longer part of the criminal code. The logbook at the Gonzales County Jail Museum lists some of the infractions committed over the years.

Leaving a Dead Horse in the Road

Willfully Leaving Open a Gate

Seduction

Lunacy

Theft of pecans

Bootlegging

Spitting on the Sidewalk During a Tuberculosis Outbreak

252

Number of jails in Texas, according to the National Institute of Corrections

1849

Year the state penitentiary at Huntsville opened, lightening the workload at county jails

48.75

Size, in square feet, of the high-security cells in the Gonzales County Jail

A Sober Legacy

Many of the jails have a gallows, either a scaffold with a trapdoor or a platform on the top floor with a hook above it for a noose. Until 1923, people sentenced to death in Texas were hanged in the county where they committed their crime; later executions were carried out via electric chair at the state penitentiary in Huntsville. Many jail gallows were never used, but in some towns, a hanging tree was used instead. Mobs who wanted to lynch prisoners attacked numerous jails in the state. Some were successful, while others were repelled by sheriffs committed to upholding the law.

On the Inside

The Milam County Jail Museum

Visitors can explore the 1895 building’s cellblock and sheriff’s family living quarters and take in the view from the (never used) hanging tower. The 1892 calaboose, a 200-square-foot cabin that served as a temporary holding cell, is across the street. 201 E. Main St., Cameron. 254-697-8963. Open Thu-Sat 10 a.m.-3 p.m., Mon-Wed by appointment.

The Old Pecos County Jail

The jail was built in 1883 and held prisoners until 1973, but its first floor was a sheriff’s residence until 2000. Names carved into the walls, cross-referenced with jail logs, show that a 1913 building addition facilitated racial segregation. Prisoners considered white were given cells with bunks, while the rest of the prisoners—which included those with German and Irish names—stayed in the old holding cell and slept on mattresses on the floor. 101 W. Gallagher St., Fort Stockton. 432-336-6316. Open for tours Mon-Fri 1-5 p.m.

The Old Bexar County Jail

Built in 1878 and closed in 1962, the jail is now the Holiday Inn Express-North Riverwalk Area. Rooms offer more creature comforts than the original cells, but some still have bars on the windows. 120 Camaron St., San Antonio. 210-281-1400