Illustration by Matt Murphy

Duuuuude

A middle-aged woman carves out a manly wave in Galveston

by Sarah Hepola

I stare at the waves from the Pleasure Pier boardwalk, whose glittering Ferris wheel makes a quirky beachside town in Texas look a bit like Santa Monica, California. Galveston’s low-key surf is often described as “crumbly,” which sounds like a cookie to me. But it rained the previous day, and the waves are sudsy, like a giant washing machine spilling with foam.

Galveston is not the best place to surf (Hawaii, probably). And it’s not even the best place to surf in Texas (South Padre, probably). But its modest waves rolling to shore make it a decent place to learn. The surf spots, conveniently located off beaches along the Seawall, offer a good launching pad for a sport that lacks easy entry.

At 49, I’ve never surfed, but I’m surfing-curious—a dangerous thing for me. Surfing is man vs. nature distilled to its essence, even if that man happens to be a woman. The first time the writer Jack London spotted a human on a surfboard, in the aquamarine waves of Waikiki, Hawaii, he was taken by the elegant mastery. “Where but the moment before was only the wide desolation and invincible roar, is now a man, erect, full-statured,” he wrote in a story called “Surfing: A Royal Sport” that would kick-start the American love affair with finding the perfect wave. This was 1911, and the idea of riding the water on a slender slice of wood was inconceivable to London, a swashbuckler who worked the Klondike Gold Rush and sailed the globe during an era when most Americans still toiled on farms.

“Full-statured” sounds like a tall order for me. My main goal is avoiding humiliation. A handful of surfers dot the gulf at 8 a.m. as I watch from the pier, but those folks look like they know what they’re doing. Forty-nine is not the ideal age to learn to surf. And this body is not the ideal body with which to learn. I’m a curvy 5’2” with arms so short my yoga instructor once dubbed them T. rex arms, though she pointed out she had the same. But middle age is a reminder that time is fleeting. If you’re wondering about an experience, there’s no time like the present.

“You’re gonna get beat up today,” says James Fulbright, opening the door to his Strictly Hardcore surf shop in a neighborhood of craftsman homes not far from the Seawall. “But it’s a good day to surf.”

I’m a couple hours away from my first lesson, so I take Fulbright’s greeting as a surfer’s benediction. Fulbright is Galveston surfing royalty. He first hit these waves at 10 years old, on a trip from his home in Houston, and mastered them in the 1970s and ’80s—surfing’s golden era. He opened Strictly Hardcore in his garage in 1985, and he’s supplied the local addiction ever since through gear, apparel, and the 5,000 surfboards he’s shaped in his on-site workshop. In the ’90s, he pioneered a very Texan iteration of the sport: tanker surfing. This involved riding long steady waves generated from ships pulling in and out of Galveston Bay—once for a record-setting 7-mile wave that lasted 40 minutes. Not for beginners.

Galveston is not a romantic surf spot. Sediment from the Mississippi River turns the water murky and brown. Also, it’s tough to feel hardcore in eyeshot of Bubba Gump Shrimp Co. But limitations can be strengths. No reefs. No waves so powerful they pull you down. “This is the absolute perfect place to learn how to surf,” Fulbright assures me.

Sally Field, of all people, turned surfing mainstream with Gidget. The 1965 TV show made surfing look kicky and youthful, a beachside kegger for a pre-kegger era. But surfing became male-dominated—a complicated tale that likely involves the 1966 documentary The Endless Summer. Filmmaker Bruce Brown’s story of two surfing bros on a global quest for the perfect wave in Australia, Hawaii, and Nigeria, among other spots, was Anthony Bourdain for the thrill-seeking male of the late 20th century. Over time, The Endless Summer became a classic, while Gidget was relegated to a nostalgic curiosity.

The Texas Surf Museum, in a gorgeous white historic building in Galveston’s downtown, will pay tribute to the city’s fabled place in this American saga when it opens later this year. Curated by a group of silver-haired former and current surfers and skaters, the museum’s trove of memorabilia captures an era during the ’60s and ’70s when thousands lined the Seawall for high-stakes competitions. For now, Fulbright will have to serve as my docent. There’s a poster in the Strictly Hardcore storefront window that reads: “Texas is a unique surfing culture. Wear it proud.”

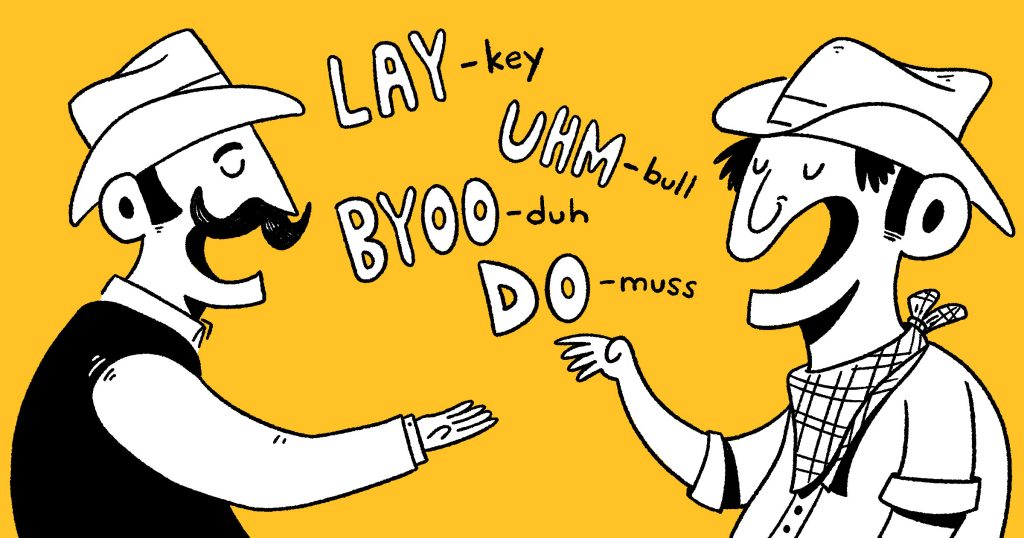

Maybe it’s inevitable that people think of surfers as Jeff Spicoli, the high school stoner played by Sean Penn in the 1982 comedy Fast Times at Ridgemont High. But the last line of the 2003 surf documentary Step Into Liquid, featuring Fulbright, makes it clear: “Real surfers don’t say dude.”

Surfing is neither fashion nor pop culture novelty but something closer to life instruction. “You have to take that step into the unknown,” Fulbright tells me when I admit I’m worried about my lesson. “Fear is what’s holding us all back. The fear of failure. Failures, a string of them, add up to small victories and successes.”

Outside on the sidewalk, I look at the bright, blue sky and the water glistening in the distance. It’s a good day to go surfing. Let’s catch some waves, dude.

I arrive at the 43rd Street pier in a black swimsuit with a ruffly halter top underneath a neoprene zip-up jacket I’d bought on Amazon for $40. In the summer, most folks book lessons through shops like Southern Spears or Ohana Surf and Skate, but this is October, a good time for Galveston waves but a lousy time to find instructors. Still, Google connects me to Valerie “Val” Johnson of Valz Surf Lessons, whose website reads: “We are the only Female owned Surf School on da island!!” A lesson costs $100.

Val tells me to look for her van, but she might as well have told me to look for Val. She is unmistakable—a skinny 5’4” with tattoos covering her tanned skin and long dark hair threaded with silver. “I wish you were staying another night,” she says as she unloads the van. “We’re doing a drum circle tomorrow.”

Val didn’t start surfing till her late 40s. This was after Hurricane Katrina, and the waves in the shipping channel were so clear, so close to perfect. She rode on her knees at first. It wasn’t until she started dating a lifelong surfer that she developed a passion for the sport. The couple has surfed in Mexico, California, Hawaii, and the East Coast. Val is 60, though she calls it “sexty.”

“I’m seeing waves that break,” she says, staring into the horizon as we haul a blue longboard to the cold sand. Surfers talk about wind patterns like meteorologists. “There’s an outgoing low tide.”

Val places the Surftech board on the sand where she’s carved out a hole for the fin, so it won’t break. She demonstrates lying on her belly as she paddles into waves, then pushes up as she slides her feet into position, staying low, arms stretched along either side.

“It’s like a cobra position into a warrior 2,” I say, a sentence that would make my yoga teacher proud, but Val only nods vaguely.

There is a Girls episode where Lena Dunham’s character lands a magazine assignment on female surfing. “Our vision is we send you out there to witness these bored surf ladies who are taking surf culture, co-opting it, turning it into some shitty yoga, which they’ve already ruined,” says her New York editor. The episode came out in 2017, when all-female surf camps had become trendy. Dunham’s character joins a trio of beach babes nailing their pop-up on the first try, but she gets so anxious she fake-injures herself to avoid surfing—then spends the next week getting wasted with her hot instructor and sleeping with him. I am 13 years sober, and Val has a boyfriend, so we’re good.

But that episode got my head spinning over the “pop-up”—the essential surfing move. The beach is empty as I try it. “Everybody looks down,” Val tells me. “You gotta look up.” It’s a lot to think about in one swift motion: feet along a white center seam, left hand pointing toward the horizon, but don’t watch yourself doing this. On my third attempt, Val seems satisfied.

“You got it?” she asks, and it’s my turn to nod vaguely. “You’ll forget it all when we get out there, but let’s go.”

The foam board is heavy as we carry it sideways to the wet lip of the gulf. For beginners, longboards are better than shortboards, which make shredding easier, but they’re also unwieldy. My hands struggle to maintain their grip on the wide surface, making me feel doomed before I’ve started. We set down the board, careful not to break the tricky fin, and Val leashes it to my ankle like I’m one of those wayward toddlers at the mall.

Lose a couple $700 Surftechs in the churn, and a leash won’t feel quite so degrading. But attaching a large board to your person as you get tossed about by Mother Nature comes with risks. “It can bash you,” Val warns me. “That fin can cut you if it hits skin.” She’s seen surfers disappear into the water only to rise up into their board with a thud. If the wave takes me down, she cautions, I must place both hands over my head. She demonstrates this like an elementary school student during a tornado drill.

“I’m nervous,” I tell her, staring into waves that seemed much gentler from the boardwalk.

“Everybody’s nervous at first, but screw it,” she says. “Let’s have fun.”

We wade into the water, cold against my legs and then torso. I’m realizing that surfing is not simply the act of riding a wave; it’s the act of navigating many waves to reach your point of departure. This is harder than I’d anticipated because the board threatens to slip from my hands each time the tide exerts its dominance. Val shows me how to push the board into a wave as one rolls over us. “Stab it!” she commands, thrusting the pointy tip into white foam so forcefully it leaves me with a face full of water. I keep one eye closed during Val’s demonstration because each time a wave rolls past, my face gets splashed.

Surfing looks so graceful from the shore, but it’s a gnarlier experience in real time—saltwater in the mouth, the relentless pounding of even mini-crumbly waves. There’s no pause button, no way to turn off the ignition. Just a humbling, unstoppable force.

The time has come. Val settles the board on the undulating water, and I slide on my belly as she stares into the horizon. “Choosing the right wave is a huge part of surfing,” she says. You look for a wave about to crest; it’ll have the power to carry you to shore. “Not this one,” she says. “Hold on to your board.” Do I have a choice? I feel helpless lying prone as water slops over my body, turning the bottom of my swimsuit into a thong. I’m grateful to have a female instructor. No time to adjust. The next wave is coming.

“Go,” she says, giving me a push, except I don’t quite hear her, so the board starts moving before I process what’s happening, and I tump over into the drink. The water is quiet and dark, the distant roar of the highway disappearing into the white noise of submersion. When I come up, I feel so embarrassed. Nature: 1, Woman: 0.

“That was my fault,” Val tells me, as I struggle to maneuver my board back to her spot. Val positions the board so I can try again. But the second verse is the same as the first. A few feet of chaotic motion, then straight into the water. My third spill is dramatic. A wave takes me so far down, I place my hands on the top of my head like I’ve just heard the blare of a siren.

“That was perfect!” Val tells me when I emerge. “You remembered to protect your head.” But I’m growing frustrated. What if we stay out here the whole time and I never get up? We booked an hour, which Val assured me was enough, but I wish I’d gone for a double session.

“Keep your hand on the board till you’re steady,” she tells me. Aha! I was popping up too fast, releasing my grip before I’d acclimated to the turbulence.

I start paddling this time, and I can see the cresting white behind me like a monster on my tail. The water rushes over the nose of the board as I push myself up but keep one knee down. I watch the gulf blur past until the moment I feel steady enough to look up to the rapidly approaching shore. I’m so excited to make it this far I forget Val’s warning not to ride to the sand, lest the fin break from impact. I pop off with seconds to spare, feeling sheepish as I plunge into the water. But I’m triumphant as I stand, hair dripping. When I turn to find Val, she’s hopping up and down and waving her arms like a cheerleader.

My next attempts are an accelerated version of a baby learning to walk. I keep one shaky knee down till I can manage a low crouch, hand to board, and then I’m close—very close!—to standing. The hardest part is dragging that beast of a board back to where Val, my tireless support squad, stands in the waves. She’s whooping and clapping, but I’m beat. Each time I bail off the board as the shoreline nears, and I stand in ankle-high water staring at a vast pool ahead of me, I feel despair. Back at the beginning again.

Male surfers dominate the sport. Kelly Slater, Laird Hamilton, Duke Kahanamoku—these are the masters. Let’s face facts: Certain bodies have an advantage. Men tend to be stronger, taller, and more predisposed to risk-taking. Women can surf too, though, and a growing number are also masters. Stephanie Gilmore, Molly Picklum, Carissa Moore.

In 1998, journalist Susan Orlean wrote a story for Outside magazine about female surfers in Hawaii. “To be a girl surfer is even cooler, wilder, and more modern than being a guy surfer,” she wrote.

The article became the 2002 movie Blue Crush, starring pint-size Kate Bosworth as a rebel proving herself in the testosterone-soaked world of competitive surfing. It’s Gidget for a girl-power era, and though it received mixed reviews, Blue Crush imprinted on a generation of young women who suddenly saw themselves in a landscape of dudes. Female surf camps in Costa Rica and Nicaragua opened in the wake of Blue Crush—the high-adrenaline version of a yoga retreat that Dunham would satirize many years later.

I watch Blue Crush after my Galveston lesson and am surprised to learn my hour in the water has equipped me with extrajudicial powers of skepticism. “Can’t do that,” I say to the screen as Bosworth paddles into a wave that’s far too big. The movie is fine, but I prefer Orlean’s article. It captures the immaculate sensation of riding the tides.

Orlean grew up in Ohio, but the girls in her story can’t believe she’s never surfed—or, as she put it, “never ridden a wave standing up or lying down, never cut back across the whitewash and sent up a lacy veil of spray, never felt a longboard slip out from under me and then felt myself pitched forward and under for that immaculate, quiet, black instant when all the weight in the world presses you down toward the ocean bottom until the moment passes and you get spat up on the beach.” But she nails the experience. The “immaculate, quiet, black instant”—that’s exactly what I feel when the waves suck me down.

Back in Galveston, my hour in the water is nearly up as I once more lug my board back to Val, stabbing the waves that beat ceaselessly to the shore.

“One last run?” she asks.

I wait to spot the white crown and begin paddling with my T. rex arms, making my way into a low crouch that rises into a fully erect posture as the wave slows. I never can manage to quit looking down, even when Val suggests I keep my eyes on a yellow building in the distance. I stare hard at that yellow building, but as soon as the board begins shaking, that yellow building isn’t nearly as interesting as the motion underneath me. I have to watch, a beginner’s habit. To be fair, I am a beginner. And though my dinky body will likely always fail at basketball and reaching high shelves, I do have flexibility, decent balance, a scrapper’s heart.

On my last run, I manage to walk up the board a smidge, making it go faster. I scan the beach, hoping to catch onlookers—I’m doing it, y’all—but only spot seagulls pecking at washed-up sea critters. I hop off the board near the shore. “Sarah, my sista!” Val hollers into the wind, pumping her arms.

Together, we lug the board back to the van. “You should be proud of yourself,” she tells me. Surfing isn’t as hard as I feared, and I’m not as good as I hoped—and that describes most of life. Screw it, I’m proud.

I pause at my car to take a selfie. Face red from exertion, hair matted in wet chunks, a portrait of triumph. The next day, I find a trio of bruises on my right knee and one on my left thigh. My arms and shoulders groan. But I did it.

I’m starving by the time I reach a pizza joint on the boardwalk. The guy behind the counter is cute, a young surfer type, and for a second, I’m embarrassed by my appearance.

“How are the waves?” he asks, working the cash register. A smile creeps across my face.

“Pretty good,” I say.

Sarah Hepola’s Open Road essay “Go West, Young Woman” appeared in the December 2018 issue.