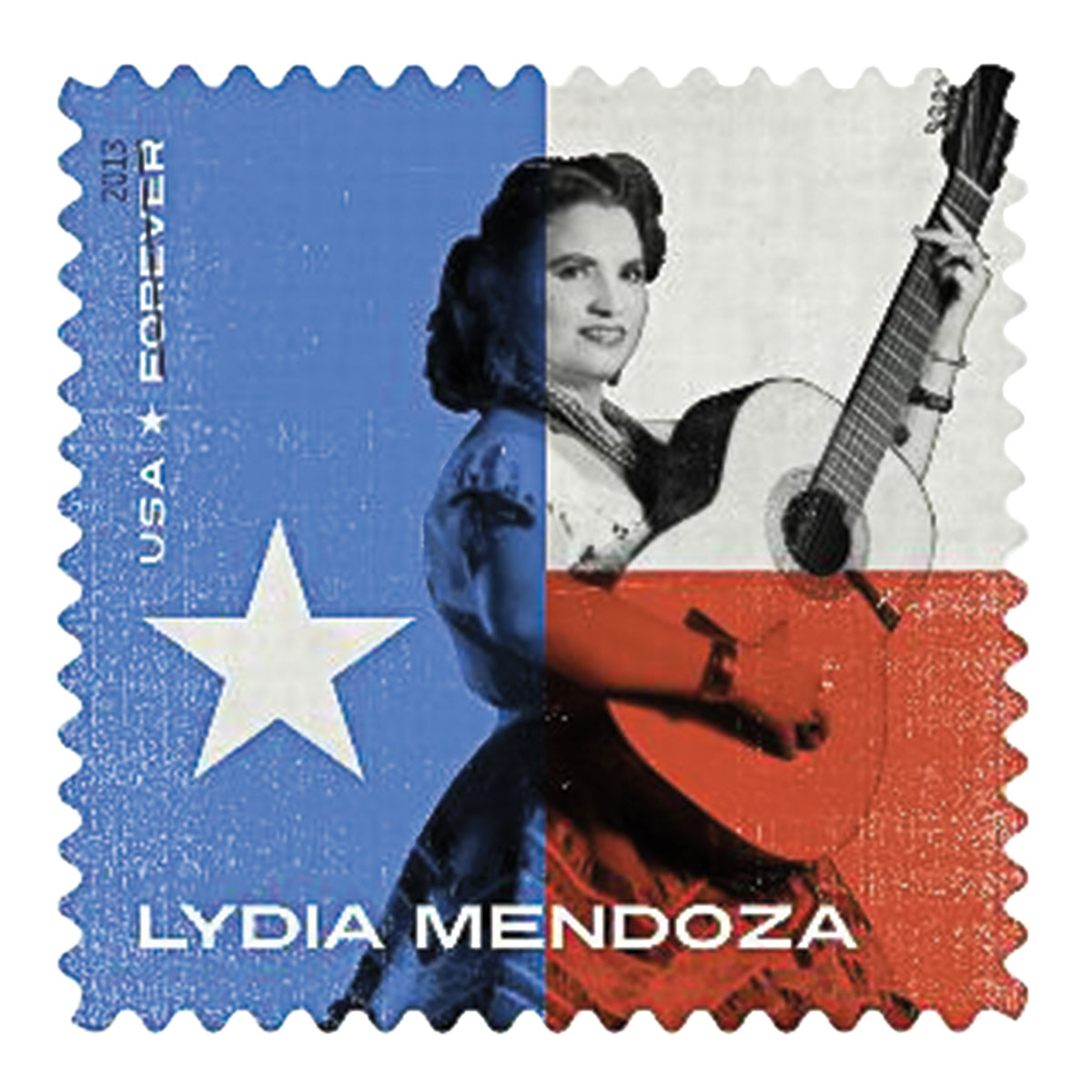

Lydia Mendoza was only a teenager when she became an icon of Mexican American music.

The year was 1934. The song was “Mal Hombre,” or “Bad Man.” A brave choice for a solo debut, the bitter tango of lost innocence and contempt forever defined her. The lyrics, quite possibly a prostitute’s lament, struck a nerve.

But the moment was more than that.

The beautiful singer from Houston with piercing Cleopatra eyes was speaking for every woman who had been hurt by a thoughtless guy. This fearless, discarded girl was willing to confront him. Though Mendoza did not write the song, she made it her own. A half-century before young pop singers Madonna and Selena embodied such defiant female empowerment, Mendoza had arrived.

“It took a lot of guts for a young girl at that time in history to sing a song like that,” said Chris Strachwitz, the musicologist who helped spark Mendoza’s revival with the 1976 documentary film he co-produced, Chulas Fronteras. “I don’t think any other woman had sung something that direct.”

The first known depiction of Mendoza appeared in a late 1934 newspaper advertisement. Her name was misspelled as “Lidya.” The drawing—outlined with shimmering rays usually reserved for La Virgen de Guadalupe—gave a face to the voice that had only been heard on the radio and in public plazas, carpas (tent shows), restaurants, and farming camps.

At the time, Texas was largely rural and poor. The Great Depression added to the economic woes in a state that had been transformed in the 1910s and ’20s by an influx of migrants fleeing the violence of the Mexican Revolution. For Latinos, Spanish-language radio pro-grams and new Victrola record players were a refuge. Mendoza was their voice.

Accompanying herself on an Acosta 12-string guitar, the self-taught teen sang and played with conviction and a street-toughened vernacular, also reflected in songs like “Tú Dirás” (You Say) and “Adiós Muchachos” (Goodbye Boys).

Bluebird Records, a division of RCA Victor, captured “Mal Hombre” on March 27, 1934, inside a makeshift studio at the now-defunct Texas Hotel in San Antonio. Mendoza’s mournful rendition, with its swooping, elongated phrases, redefined the relationship between artist and audience. She was one of them.

Mendoza’s powerful voice was hardly operatic or sophisticated in the classical sense. But this forlorn child of the Jazz Age was versed in the styles of contemporary singers found in her father’s meager record collection, such as Italian opera singer Enrico Caruso and Cuban-born Pilar Arcos, a popular New York soprano jazz and tango singer.

With a raw guitar style—not unlike Texas bluesman Lead Belly, who also rose to prominence in the 1930s—Mendoza added her own flair, including the pasadas (passing chords and melodies) used by conjunto bajo sexto players. She was versed in boleros, tangos, waltzes, corridos, and rancheras.

There was profound beauty in the sadness of Mendoza’s songs. She sounded like she’d lived them. Conjunto music legend Flaco Jiménez once described her voice as “like listening to the stars fall out of the sky.” From those earliest days of her solo career, Mendoza was known as La Alondra de la Frontera (Lark of the Border) and La Cancionera de los Pobres (Songstress of the Poor).

Strachwitz, the founder of Arhoolie Records who traveled the South recording a treasure trove of folk music in the 1960s, recalled the first time he met Mendoza in the early ’70s. She was making tamales at her Houston home. For him, she remains la unica (the only one), the Queen of Tejano music. With Mendoza and coauthor James Nicolopulos, he documented her life in the 1993 book Lydia Mendoza: A Family Autobiography.

“The story of ‘Mal Hombre’ was part of her DNA and the DNA of many women,” Strachwitz said.

Born in Houston on May 31, 1916, Mendoza had an impoverished and nomadic childhood. Her father, Francisco, a violent man when drinking, often uprooted the family to Monterrey, Mexico, where he had worked at a brewery. Her mother, Leonor, was a self-taught guitarist, singer, and songwriter.

Mendoza took solace in musical instruments. When her mother made the guitar off-limits, Mendoza fashioned one out of a wooden board and rubber bands. By the time she was 8, she was accomplished on guitar. She also taught herself the mandolin, violin, and piano.

In a story with echoes of the Carter Family—the influential country band from Virginia that made its first recordings in the 1920s—the Mendozas forged a family group, Cuarteto Carta Blanca, with the parents singing in unison with Lydia and one of her sisters, Francisca. Young Lydia played the mandolin. They traveled to San Antonio in 1928, enduring several flat tires, to answer an ad to make a recording for Okeh Records.

But the road to “Mal Hombre” actually began two years earlier in Mexico. At a humble Monterrey theater, Mendoza first heard the song that would change her life. Her father had brought her to see a musical variety show. A young woman appeared onstage to sing two tangos. One of them was “Mal Hombre,” a song most likely of Argentine origin.

Mendoza couldn’t believe it. She had the words to the song in her pocket, she recounted in her autobiography. In those days, a couplet or stanza of a song’s lyrics would be printed on the wrappers of Mexican chewing gum. Mendoza collected them. The youngster was familiar with the song’s heartbreaking words, if not its melody. The girl listened intently. She didn’t care much for the singer, whom Strachwitz said may have been recording artist Elisa Berumen. Lydia was too busy memorizing the melody to later arrange on her guitarra doble.

By the late 1930s, Mendoza was the most beloved Mexican American performer of the common man. Accounts of her first appearance in Los Angeles in 1937 described thousands in the street outside the Mason Theater.

But her career was short-lived: Mendoza stopped touring in her 20s because of the economic pall of World War II and the demands of becoming a mother. She would later briefly reunite with her family’s vaudeville-style act and continue recording for small labels. Later, after Strachwitz’s film, she was rediscovered and honored during the Chicano movement of the 1970s.

An Unsung Hero

A bronze bust of Lydia Mendoza greets visitors as they enter the Texas Music Gallery within The Wittliff Collections at Texas State University in San Marcos. Created by sculptor Clete Shields, the bust is decorated with scenes from Mendoza’s life and is positioned near the bust of another titan of Texas music, Willie Nelson. Mendoza’s talent, independence, and determination embody the theme of “The Songwriters: Sung and Unsung Heroes of The Wittliff,” an exhibit I curated in my position as Texas music curator at the Wittliff. Mendoza reminds us that Texas music has always been much more than Willie and Waylon and the boys.

The exhibit —open through September 2023—also features a poster based on a Bluebird Records newspaper advertisement from 1934, which is believed to be the earliest known depiction of Mendoza. Guests can view one of the beautiful handmade dresses Mendoza sewed herself and wore onstage.

For guitar aficionados, a rare example of a 1930s Acosta brand 12-string guitar similar to the one Mendoza played is on display.

The Wittliff Collections at Texas State University opens Mon-Fri 8:30 a.m.-4:30 p.m. Weekend hours vary. 512-245-2313; thewittliffcollections.txstate.edu.

Then in her 60s, Mendoza lived in a modest home on Beverly Street in the Heights area of Houston. She sewed and decorated her colorful sequined stage dresses by hand: If a light was on in the house, she was sewing, her granddaughter Ann McKinney recalled.

“She called me ‘mijo,’” remembered conjunto accordionist Santiago Jiménez Jr., Flaco’s brother, who recorded in San Antonio with her in the early ’60s. “Lo puedes hacer,” she assured the young musician. You can do it. Everything was one take. “She played with all her soul,” he said. “She had no fear.”

Despite her greatness, she had troubles, too. In the late 1980s, Mendoza poured out her heart to Denver play-wright Anthony J. Garcia with harrowing accounts of domestic abuse and struggles with alcohol. Garcia presented his 1991 play, Lydia Mendoza: La Gloria de Tejas, at the Guadalupe Theater in San Antonio. The singer attended the opening in a white limousine.

In those days, Mendoza didn’t sing without a six-pack of beer nearby. Fans always called out song requests, and Mendoza would oblige. She continued performing through the 1990s until she suffered a stroke. Mendoza died at age 91 in San Antonio on Dec. 20, 2007.

Mendoza’s grave is in a quiet, sunbaked area of San Fernando Cemetery No. 2 near the corner of Castroville and Cupples roads in San Antonio. Next to a flat headstone, a Texas Historical Commission marker honors Mendoza as “one of the first and most famous singers of the Texas-Mexico border and Latin America … famous for both her voice and skills playing the 12-string guitar.”