Late-morning sunlight warms the sculpted surfaces of the Armstrong Browning Library and Museum’s bronze front doors, which bear bas-relief depictions of scenes from Robert Browning’s poems. My hand closes around the torch-shaped handle, worn shiny by the grips of thousands before me. I pull, but the three-quarter-ton door barely moves. With my entire weight, I slowly pry it open and slip inside, where Jennifer Borderud waits in the foyer, amused. She’s watched this scene play out before, as library visitors arrive unprepared for the heavy doors—or what they’ll find on the other side.

“People have no idea what they’re about to get into when they walk into the library,” says Borderud, the library’s director. “They don’t expect a building like this to be in Texas, or in Waco.”

Stained-glass windows filter the sunshine into a muted blue that reflects off the foyer’s marble walls. Above, the ceiling is carved into an elaborate octagon pattern. I feel the urge to whisper: The imposing space inspires a sense

of reverence I associate with temples and cathedrals.

The Armstrong Browning Library and Museum, 710 Speight Ave. in Waco, opens Mon-Fri 9 a.m.-5 p.m. and Sat 10 a.m.-2 p.m. Self-guided tours available; call ahead for guided tours. Donations accepted. 254-710-3566.

The library, which is part of Baylor University, houses the world’s largest collection of materials related to Robert and Elizabeth Barrett Browning, prominent English poets of the Victorian era. The two famously courted by mail, exchanging more than 560 love letters before they married in 1846. Elizabeth later wove phrases from those letters into Sonnets from the Portuguese, which includes her most famous work, “Sonnet 43: How do I love thee?” It opens with the indelible line, “How do I love thee? Let me count the ways.”

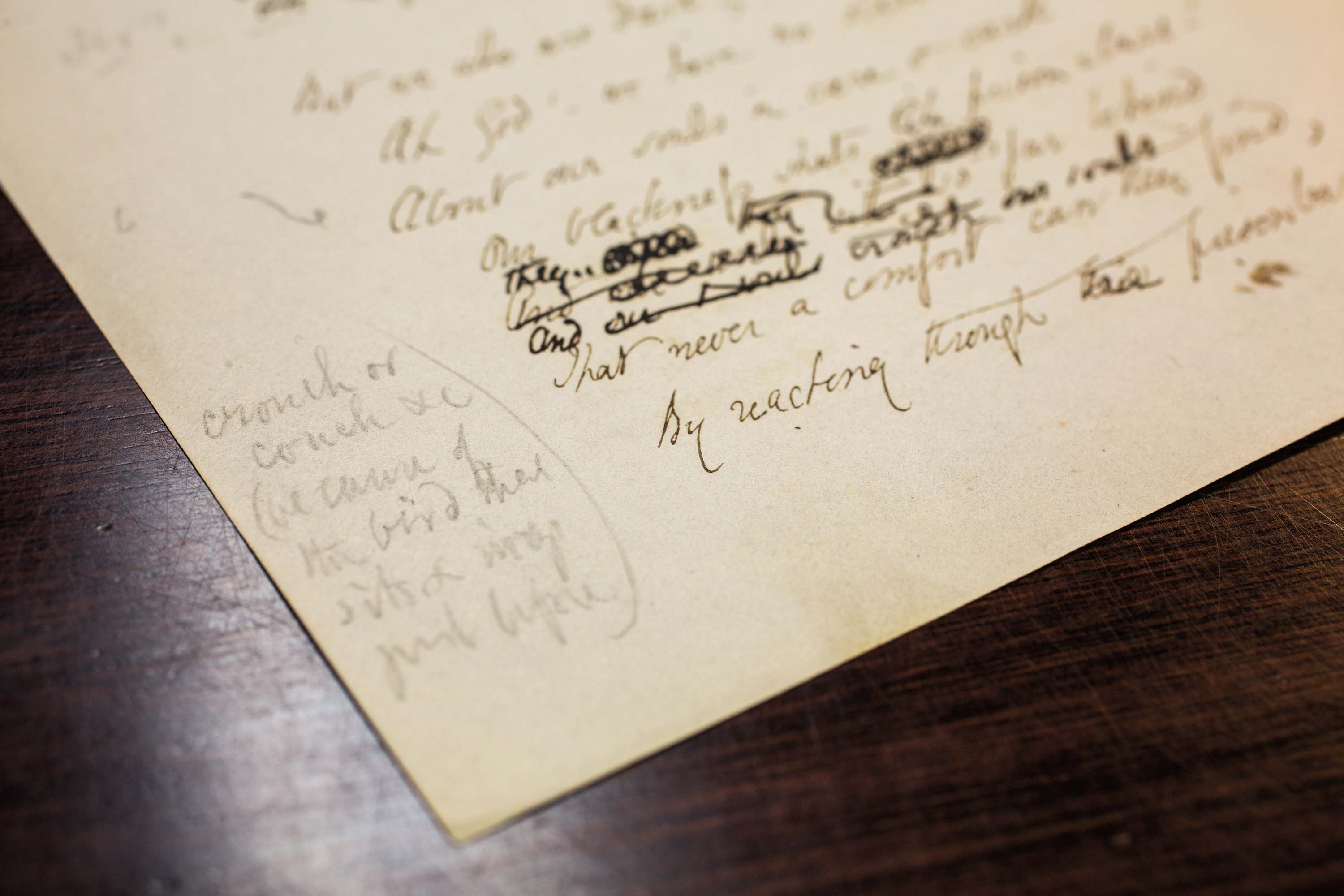

The library’s research collection includes many of the Brownings’ original manuscripts and handwritten letters, as well as other materials related to 19th-century literature and culture. While these treasures draw researchers from around the world, the library also welcomes curious visitors for self-guided tours that showcase the Brownings’ writing desks, various personal belongings, and perhaps most striking, the breathtaking building itself.

Interestingly, the Brownings never visited the United States, and they may never have heard of Waco. Baylor houses their materials because of the determination of A.J. Armstrong, who chaired the university’s English department from 1912 to 1952. Armstrong admired Robert Browning’s work and amassed a collection of the poet’s papers. After Armstrong donated the collection to Baylor in 1918, he and his wife, Mary Maxwell Armstrong, set about raising money to build a dedicated library. They brought poets—including Robert Frost and W.B. Yeats—to campus and organized overseas tours for scholars and Browning literary clubs. The proceeds were funneled to the construction of today’s three-story Italian Renaissance building, which opened in 1951.

Adjacent to the foyer, the John Leddy-Jones Research Hall, with its walnut-paneled walls and long tables, is a popular study spot for Baylor students. Stained-glass windows—the library has 62—illustrate scenes from Robert Browning’s poetry, including “The Pied Piper of Hamelin,” based on the German folktale. In the Hankamer Treasure Room, a glass case displays an envelope and pressed flowers that were part of the Brownings’ romantic correspondence. The two, who were familiar with one another’s work, were introduced by English poet John Kenyon. Kenyon encouraged Robert to write Elizabeth after she mentioned him by name in a poem. Though they had never met, Robert began his first letter, written in January 1845, “I love your verses with all my heart, dear Miss Barrett,” and later in the missive, boldly wrote, “and I love you too.”

More stained-glass windows in the Elizabeth Barrett Browning Salon—modeled after a 19th-century living room with the poet’s desk as the showpiece—tell the story of their secret courtship. The two met in May 1845 when Robert began visiting Elizabeth, who suffered from frail health, including a lung condition, at her home in London. For reasons unknown, Elizabeth’s father forbade his 12 children from marrying, so the couple wed in secret in September 1846, when Robert was 34 and Elizabeth was 40. They moved to Florence (the inspiration for the library’s Italian influence), and three years later Elizabeth gave birth to their only child, Robert Wiedeman Barrett Browning, whom they called “Pen.”

Elizabeth was the more popular of the two poets during her lifetime, says Joshua King, the library’s scholar in residence. Robert’s work received more attention in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, but today, Elizabeth is again the more widely read poet.

“It wasn’t all that common for a woman, after marriage, to be regarded by her husband not only as his peer but even sometimes as his superior.”

“It wasn’t all that common for a woman, after marriage, to be regarded by her husband not only as his peer but even sometimes as his superior,” says King, an associate professor of English at Baylor. “I think Robert Browning was not only a tremendously gifted poet, but someone who was able to recognize his wife’s gifts.”

“Sonnet 43: How do I love thee?” is one of 44 she wrote during the Brownings’ courtship, inspired by phrases from their letters. Elizabeth didn’t show the poems to Robert until three years after they married.

“When he read them, he thought they were the best sonnets since Shakespeare’s and that they had to be published,” Borderud says. “But because they were so personal, they decided to call them Sonnets from the Portuguese, hoping people would think they were some obscure Portuguese sonnets that Elizabeth translated into English.”

The public, however, wasn’t fooled.

“Sonnet 43” plays a role in the McLean Foyer of Meditation, where the ceiling soars 40 feet overhead, and lofty opaque windows are flanked by columns of Italian marble. A 2-ton bronze chandelier is suspended from within a recessed dome in the ceiling. Workmen pressed the 23-carat gold leaf into the plaster there with their thumbs, Borderud says, creating the illusion of a velvety texture. Marble benches along the walls are topped with velvet cushions bearing the same golden sheen. A mysterious amber light filters through the tinted windows and pools on the polished floor.

“Dr. Armstrong wanted there to be a room in the building that was just a place of beauty, where people could sit and be inspired—maybe to be the next Chaucer or Shakespeare or Browning,” she explains.

On April 24, the Armstrong Browning Library and Museum will celebrate its namesake poets with Browning Day. Barbara Neri, a Michigan-based artist and scholar, will speak about Elizabeth Barrett Browning’s wardrobe and its influence on her image. Browning Day takes place annually on a spring date between the birthdays of Elizabeth (March 6) and Robert (May 7).

Borderud leads me up a few steps to a recessed alcove in one wall. Here, tucked behind a marble archway, is the Cloister of the Clasped Hands, a little nook that takes its name from a bronze cast of the Brownings’ hands. American sculptor Harriet Hosmer, a friend of the couple, made the piece. “This is considered a very romantic spot on campus,” Borderud says.

It’s easy to see why. The walnut paneling on one side of the alcove is inscribed in gold with “Sonnet 43,” which ends: “And if God choose, I shall but love thee better after death.” The opposite wall bears the invocation to Robert Browning’s acclaimed verse novel The Ring and the Book, which he wrote several years after Elizabeth died at age 55 after a lifetime of illness. Robert declares she is still his muse: “O Lyric Love, half-angel and half-bird, And all a wonder and a wild desire, … still, despite the distance and the dark, What was, again may be.”

Every year, the poets’ devotion to one another inspires the numerous couples who get engaged in the cloister and who marry in the Foyer of Meditation. In a city they’d never visited, 130 years after both of their deaths, the Brownings’ romance lives on.