Before I made Texas my home,

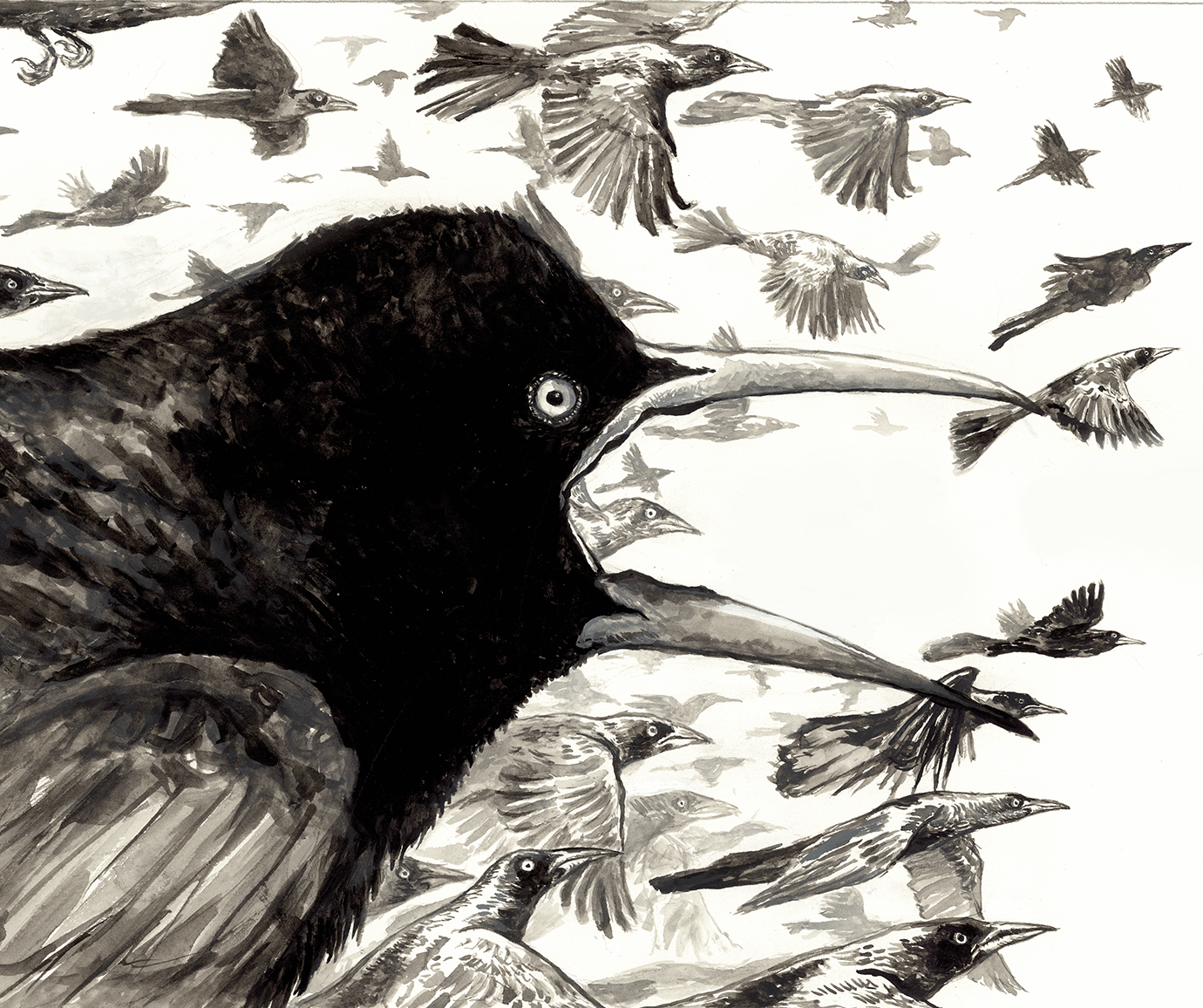

I was entirely ignorant of grackles. I am from England, and I’d been looking forward to seeing new creatures in my new home—armadillos, for example, a few snakes, perhaps even a puma (from a distance). No one told me about grackles. No one talked about grackles. But here I was, and there they were, seemingly all about Austin, from parks to parking lots. Strange black broken umbrellas making their noise of disquiet. “What is that?” I asked a native, pointing to the shadowy thing. “A grackle,” the shrugged response. Good heavens.

“Grackle” does not sound like a bird’s name. Rather it is the description of a noise, something between a grate and a cackle. When I came to live here in 2010, I thought at first this was the local nickname, but I soon learned it’s their actual name. The word grackle is derived from “graculus,” a New Latinism meaning “jackdaw,” which is a European crow. “Gracula” is a variation of graculus. In 1772, the word “gracule” was first used in English as a modern adaptation of the Latin. “Dracul” is the Romanian word for the devil. It is not taking it so very far to see these birds as descendants of Vlad Tepes, the Impaler, who inspired Bram Stoker’s vampire.

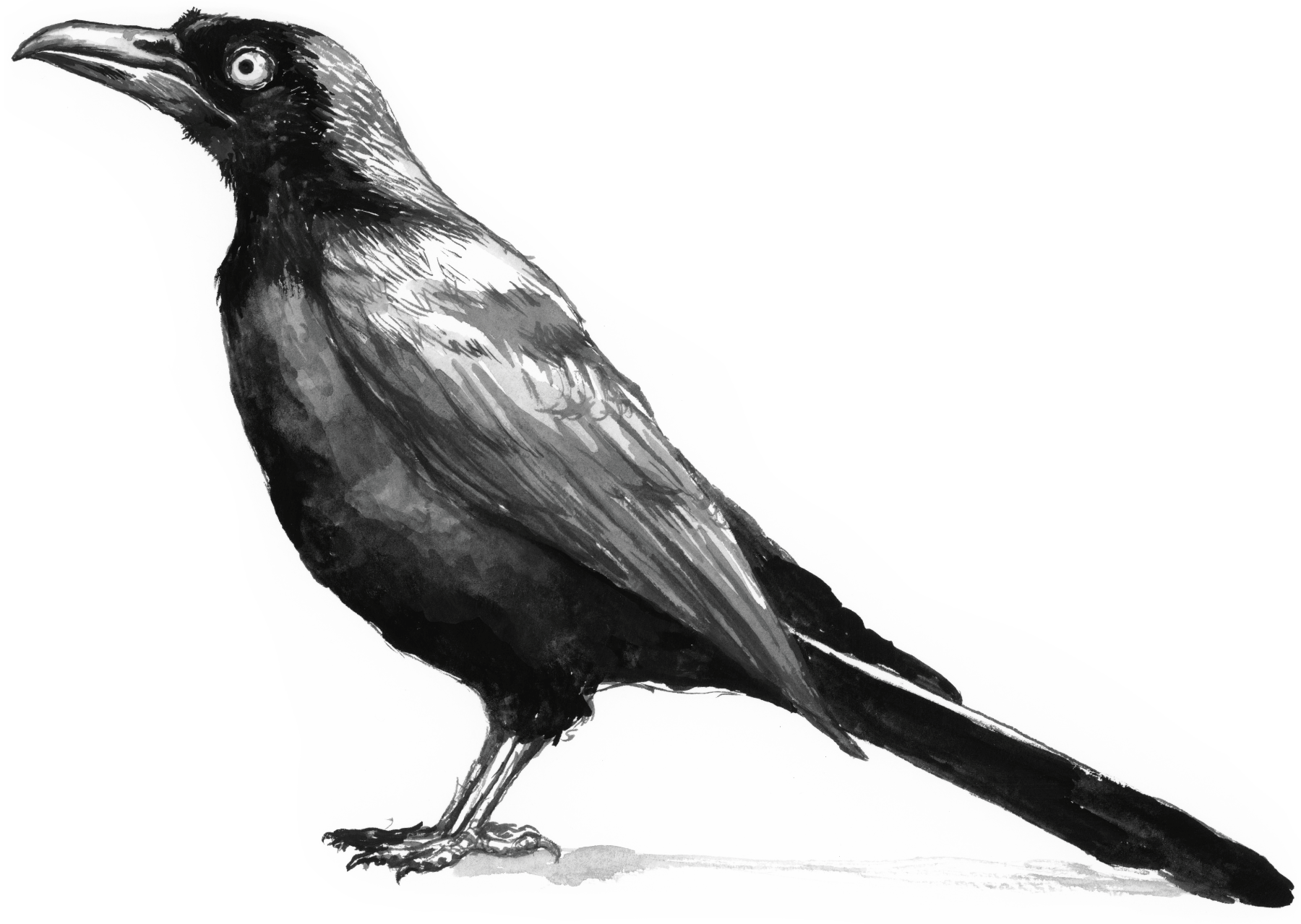

There are three species of grackle. The common grackle, the boat-tailed grackle, and the great-tailed grackle. The common grackle is the one that migrates long distances. There are two forms of common grackle: the bronzed grackle and the purple grackle, both smaller than the other two species, with a shorter tail and smaller bill. The boat-tailed grackle is a marsh bird and in general keeps close to the water. Unlike the other two species, it prefers to stay near the Atlantic and Gulf coasts and has little interest in world domination unlike the great-tailed grackle, with a habitat covering more and more of America. It has not yet reached the East Coast but hopes to very soon. The great-tailed grackle, with its menacing yellow eyes, is the subject of this essay, our hero—or villain.

Solomon Grackle, Solomon Grackle

Has the most terrifying cackle,

He screeches in the street

And stole the butcher’s meat.

To shut up the singing lark

He screeches in the city park.

He hides in church places

To fright all the sad faces

Waiting for the mourners

He lurks in dark corners

And when out they weep

He gives a shrilling shriek.

Gracklesong for use in the household

Monday’s grackle is fleet of foot.

Tuesday’s grackle is made of root.

Wednesday’s grackle eats old people’s fleas.

Thursday’s grackle invites disease.

Friday’s grackle rips open doves.

Saturday’s grackle steals little loves.

Sunday’s grackle is in the house.

This is the house that grack built

It is made of old skin and bones, hair and moans, dead flies,

children’s cries. It has twists of rusted wire and a baby’s pacifier, it is

made of dolls’ clothing and secret loathing. That is the house that grack built.

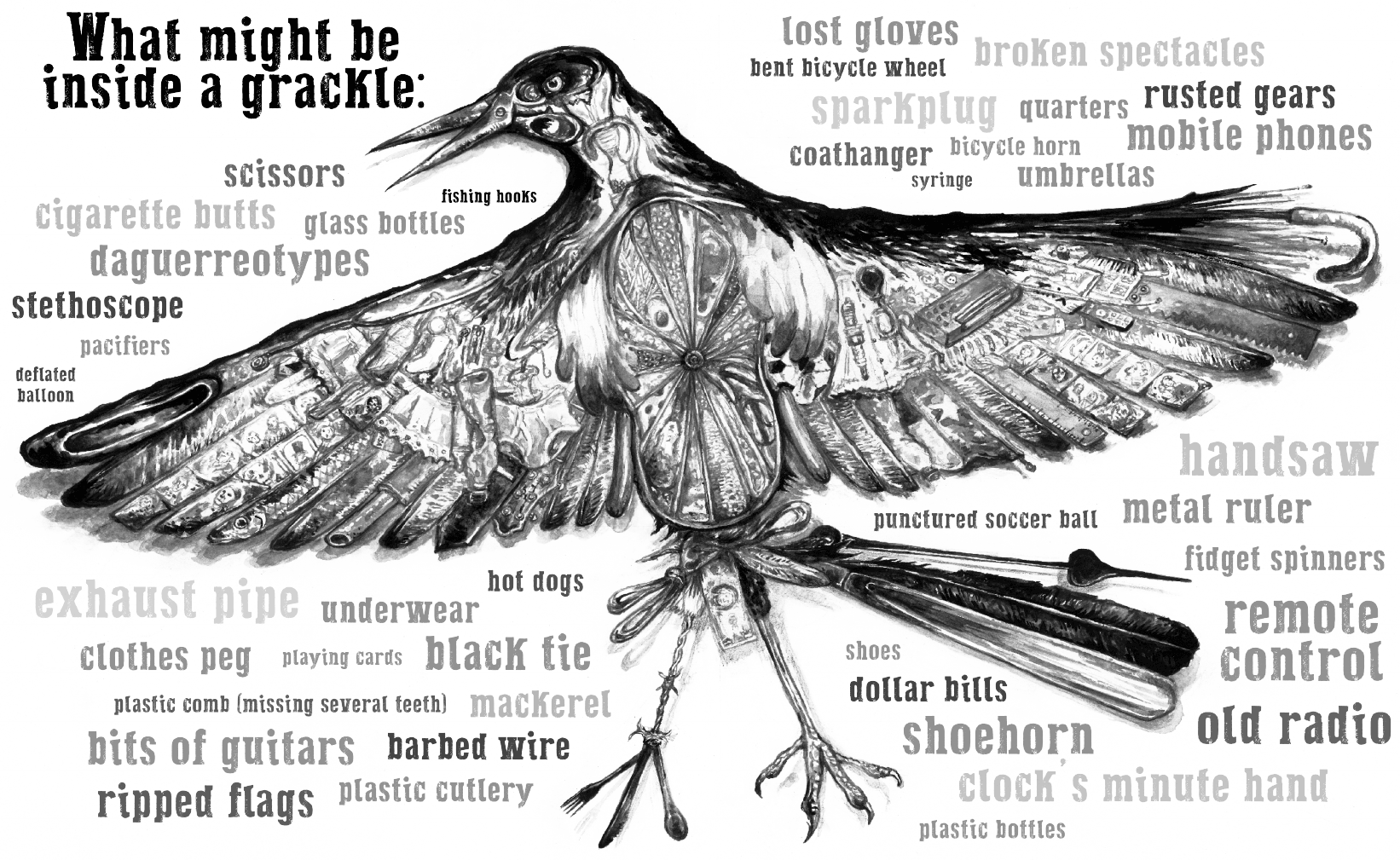

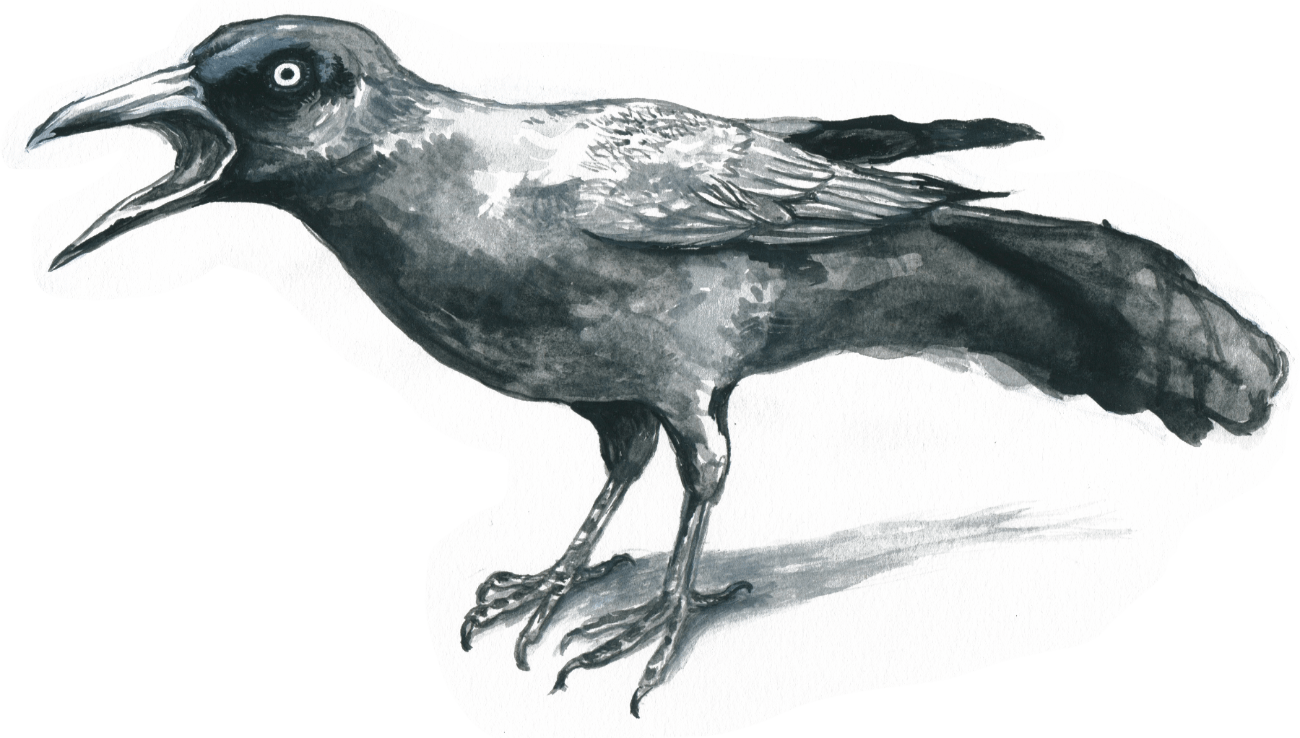

The grackle is a rather discouraging, miserably vicious-looking bird. Many people loathe it, but I have an increasing fascination for it. A grackle is living proof of monsters, of goblins, of creatures that we otherwise claim as fiction. At times I do not think it can be a bird at all. Perhaps it is actually a thing, a thing made from the souls of dead glum people. It appears not to be made up of feathers and flesh but rather of old leather, bits of broken umbrellas, of torn kites, of old Victorian ladies’ fans (or old Victorian ladies), of abandoned toupees where the rubber underneath the hair is very visible. Instead of a rib cage, perhaps its anatomy boasts a rusted and bent bicycle wheel, or perhaps a coat hanger. For lungs? Abandoned gloves (medical ones, most probably). Its long tail feathers might be a shoehorn or the minute hand from an old station clock. Surely a black tie from a funeral is among its wing feathers. Perhaps a handsaw, too, an exhaust pipe, a ripped flag, a hot dog, a shoe, a stethoscope, dollar bills, bin liners, plastic bottles. Sometimes, looking at the grackle, I wonder if its legs are made of barbed wire and its feet plastic cutlery.

Am I being unfair? It’s just that grackles seem somehow constructed, artificial, made up. The noise they make, too, is not like any noise I’ve ever heard coming from any other bird. It doesn’t sound like anything in any way natural. It sounds man-made, like the loud and unwelcome shrieks of rusty machinery. It sounds mechanical. It sounds like something failing.

The grackles hop and strut outside my home, looking grimly at everything, twisting their heads, letting forth their attitude. They have no majesty. They look like beggars, plague doctors, bitter humans sucked of all juice. There is nothing liquid about grackles; they are all cartilage. Sometimes you see a flash of blue or purple in their iridescent tail feathers, and this seems to have come from some of the color glimpsed as you move an old daguerreotype in your hand. Perhaps they are the physical embodiment of lost portraits of the dead. They are what happens to photograph albums after they have been abandoned or lost or orphaned. Living with these creatures seems unwise and full of bad luck, but there is something almost mythical in watching morphed human souls or burnt abandoned objects taking a vaguely bird-shape form, hopping, screeching, perching on everything, accusing, lamenting, blaming, chattering, shrieking, laughing as you go about your personal business.

I can’t help but think of the French anthropologist Claude Lévi-Strauss’ famous comment that animals are “good to think with.” Looking at grackles—unafraid, indifferent, suffering from verbal diarrhea, with never an unexpressed thought—it is tempting to think they are commenting on humanity. I suppose there are old nursery rhymes about grackles because the creature is so illustrative, so ripe for storytelling. They also seem like they would fit very neatly into children’s cautionary tales. Surely some old, deceased-age grackle tales were told in the household by the light of a fire to infants who would not settle. Surely once upon a time in Texas, where these things dot the landscape in abundance, parents soothed their babies to sleep by singing old lullabies about grackles. But I have not found any, and so I have made some of my own, a handful of which I have dropped in here as possibilities.

Grackles are natives. They belong here. This is their home. But they are also extending their home throughout North America, making themselves at home everywhere. Their noise is the soundtrack to our lives in this part of the world. Grackles move around urban streets taking control, stealing from humans and from birds, dominating smaller birds, even eating a sparrow out of sheer fury. They congregate outside supermarkets and sing their long and raucous operas every evening.

I asked the novelist and Texas historian Stephen Harrigan about grackles. I wondered if he knew of an instance like, for example, that of geese saving Rome in 387 B.C. by alerting the populace with their honking to an army of Gauls come to invade. If not that, then maybe something along the lines of pigeons acting as messengers during World War I. Were grackles at the siege of the Alamo perchance, providing commentary? Harrigan can’t help me there, but he does, characteristically, have an eloquent response to the creature: “What strikes me as special about grackles is that they’re among the easiest birds to contemplate. You don’t need binoculars to see them, they’re not skittish around humans, and they’re sort of always there. The more I look at them, the more I understand the link between birds and dinosaurs. In the way their bodies are conformed—and the way they strut around, alert and knowing—they seem to me like miniature velociraptors.”

I agree with him, though they seem to me also modern somehow—and the bird we deserve. As humanity extends its mark upon nature, so the grackles increase.

Cliff Shackelford, statewide ornithologist for the Texas Parks and Wildlife Department, is a walking encyclopedia of birds. He was able to offer some specifics: “The increase in the great-tailed grackle is a direct result of urbanization just like with the explosion in rodents and roaches in our cities, all of which benefit from man’s doings. Not everyone considers them a nuisance. I’ve heard from several birdwatchers who claim it’s their favorite species because they’re interesting to watch, especially when males display to females in springtime. Plus, folks are amazed at the variety of bizarre sounds made by the males.”

Old Black Coat

Screech screecher, beak

clatter, snap snapper, black

maker, black giver, black

matter, matter matter, natter

natter, mutter mutter, screech!

Ka-reek, Ka-reek, crack,

crack, crack, crack. Old

black coat.

Speak Truth

A long-legged wild dog is called a jackal

No one has ever seen a dead grackle.

Gracky, Gracky, Raw Throat

Whither do you yell and gloat,

Is it because you can tell

Which of us is bound for hell?

Grackles seem always to be performing. Not just the males putting on the deafening displays of courtship as they fluff their feathers, but also stalking and watching and pushing others out of the way.

In Mexican folklore, the zanate, which is what the grackle is called in Spanish, was silent at creation. But then it stole seven songs from the sea turtle. The noise a grackle makes certainly feels like a strangulation: unharmonious, unlovely, purloined. It seems when the grackle stole the turtle’s songs, it neglected to learn them very well—or in its performance, the songs, possibly cleverer than their stealer, betray the crime in performance. Is the grackle desperately trying to get the songs right but ever failing? Does it have a distant memory of a beautiful noise, and yet each time it attempts to reproduce it, it’s cursed with its own creaking cacophony? Or, over time, has the grackle made the turtle’s songs its own—a sound astonishingly lovely to other grackles? Regardless, no one makes music like the grackle.

Grackles tell it like it is. Endlessly quarreling, singing out of key, keeping close together, yet always seeming alone. Physiognomy would declare grackles villains—those pointy beaks!—and yet they are just themselves, stubbornly, wonderfully, darkly, noisily the grackle. They are superbly dramatic, dressed in mourning like Hamlet, and as they slope along there’s something of Richard III in them. They are always theatrical, always soliloquizing. They are also evidence of survival, heroes of longevity, of a singular life.

Grackles add salt to our daily diets. Or is it a memento mori? Whatever it is, whatever they are saying, they are these shadows in our lives, our daily shadow, not going anywhere; they are going everywhere. Coming soon or here already, grackles scream on.