I’m a quixotic traveler, more drawn to a new place when I’ve been beguiled ahead of time by a story about my destination. That story might come from a novel, or it could be biographical, concerning a singular person who lived in the place or passed through—a widowed queen wandering around the castle, a down-on-his-luck explorer scoping the rapids. Really the more romantic—cliché, even—the better. Why is it, I’ve wondered, that I most enjoy travel when I can tie that kind of tale to it? To me, it seems like a small failing, but a failing all the same, the impulse to lean on a narrative rather than appreciate a place directly.

Last fall this tendency took me to the McDonald Observatory in far West Texas. It was my second visit; the first had come 12 years earlier, when I wrote a magazine article about an experiment there. Back then, I’d come across a sentence in a history of the observatory about an astronomer named Alice Farnsworth. She was a professor at Mount Holyoke College in Massachusetts who’d traveled to Fort Davis to visit the observatory in 1941. Farnsworth didn’t have any bearing on my article, but she stuck with me long after I’d forgotten the rest of my research, which is to say certain questions stuck with me. What had it been like to be a female astronomer in 1941 and to travel to such a remote place? What was she working on? How had she been received?

I returned to the McDonald Observatory to look for Farnsworth, though in a sense I knew I wouldn’t find her. When the observatory opened in 1939, it was operated by the University of Chicago, and records from that era—including the telescope log books that might indicate which nights she was observing—are stored at the university. Farnsworth visited the observatory only briefly, on the tail end of a sabbatical she took during the 1940-41 academic year, so it’s not as if I expected to discover that she’d scratched her initials into the side of the telescope. I wasn’t really looking for anything concrete. I went there in order to better imagine her there.

My first trip to West Texas, as a young reporter, had been 23 years earlier. It’s hard for me to fathom that so much time could have gone by, that this number of years, 23, is about equal to the number of years I’d been alive then. On that trip, I rode from Austin to Hudspeth County in a van full of Greenpeace activists who opposed the planned construction of a nuclear waste dump. They were headed out to testify at an administrative hearing, and I was tagging along to write about the controversy. “I’m going to the Chihuahuan Desert,” I remember telling friends back on the East Coast, where I am from, over the phone. I had recently moved to Austin, and to me that sounded both exotic and hilarious, which I suppose is how much of Texas struck me when I was a newcomer.

And then came the actual drive: the endless vistas, that particular color palette of blonde and sage and purple. I do not remember a thing about who else might’ve been in that van, only gaping out the window at the scenery. The hearing the next day took place in a big hollow room—a high school gym, I suppose—but it might as well have been staged out in the brushlands. The administrative law judges and the testifying parties could’ve just as well been scattered among the rocks and the creosote—for me, at least, the drama belonged to the setting more than anything else.

In the years after that, I went on many other reporting trips to West Texas and elsewhere. None of my subsequent trips west would elicit the kind of astonishment I’d felt the first time I went out there. But on every visit to that part of the state I am still moved by aspects of the landscape—a rock formation, a canyon, the morning mist wreathed around the mountains, the huge sky.

On this trip I was especially struck by the upthrusts of maroon rock that line State Highway 118, the road that takes you from the town of Fort Davis to the observatory. The 15-mile drive unfolds in ecological stages, as you climb from tawny grassland into the greener, juniper-

studded Davis Mountains. In the middle of the ascent are great igneous accordion folds, imprints of volcanic convulsions from millions of years ago—stunning reminders of the sweep of geological time.

Then the land levels out for a bit, and you begin to think that maybe you’ve taken a wrong turn, that you somehow missed the observatory. But you round a bend and suddenly there, on top of a mountain, are two singular white protrusions. From a distance, they look like helmets made out of PVC pipe. In fact, they are large telescopes. Another minute’s drive reveals a third telescope, atop a neighboring crest, with a silver dome.

Only one of the three would’ve greeted Farnsworth in 1941: the observatory’s inaugural telescope, which when it was built had the second-largest mirror in the world, at 82 inches. Originally known simply as “the 82-inch,” it was renamed in 1966 for Otto Struve, a Russian émigré and University of Chicago professor who was the McDonald Observatory’s first director (and concurrently the director of Chicago’s Yerkes Observatory.) These days, as one of the longest-serving major telescopes in the world, the Otto Struve also has a nickname: the old lady.

Farnsworth, who lived from 1893 to 1960, is an obscure figure but not a vanished one. She left behind a dim trail. A Wikipedia page exists, and her papers are archived at Mount Holyoke, where she studied as an undergraduate and then returned to teach after receiving her doctorate from the University of Chicago. She oversaw the college’s Williston Observatory, tracking sunspots and lunar occultations—in which the moon obscures another celestial object—with the help of students. In her spare time, she was a serious pianist, a birdwatcher, and a Scrabble fiend.

In 1941, he told me, a woman likely wouldn’t have been allowed to use the telescope unless she was accompanied by a man.

To judge from photos, she was petite—maybe 5 feet tall—with wide-set eyes and a slight skew to her lips, a passing resemblance to Lady Bird Johnson. As an undergraduate she had a reputation for intellectual stubbornness, a useful trait for anyone aspiring to be a scientist, especially a woman, especially circa 1916. A yearbook entry for her reads, “Wanted: Any argument in any line that will have any effect on Alice.”

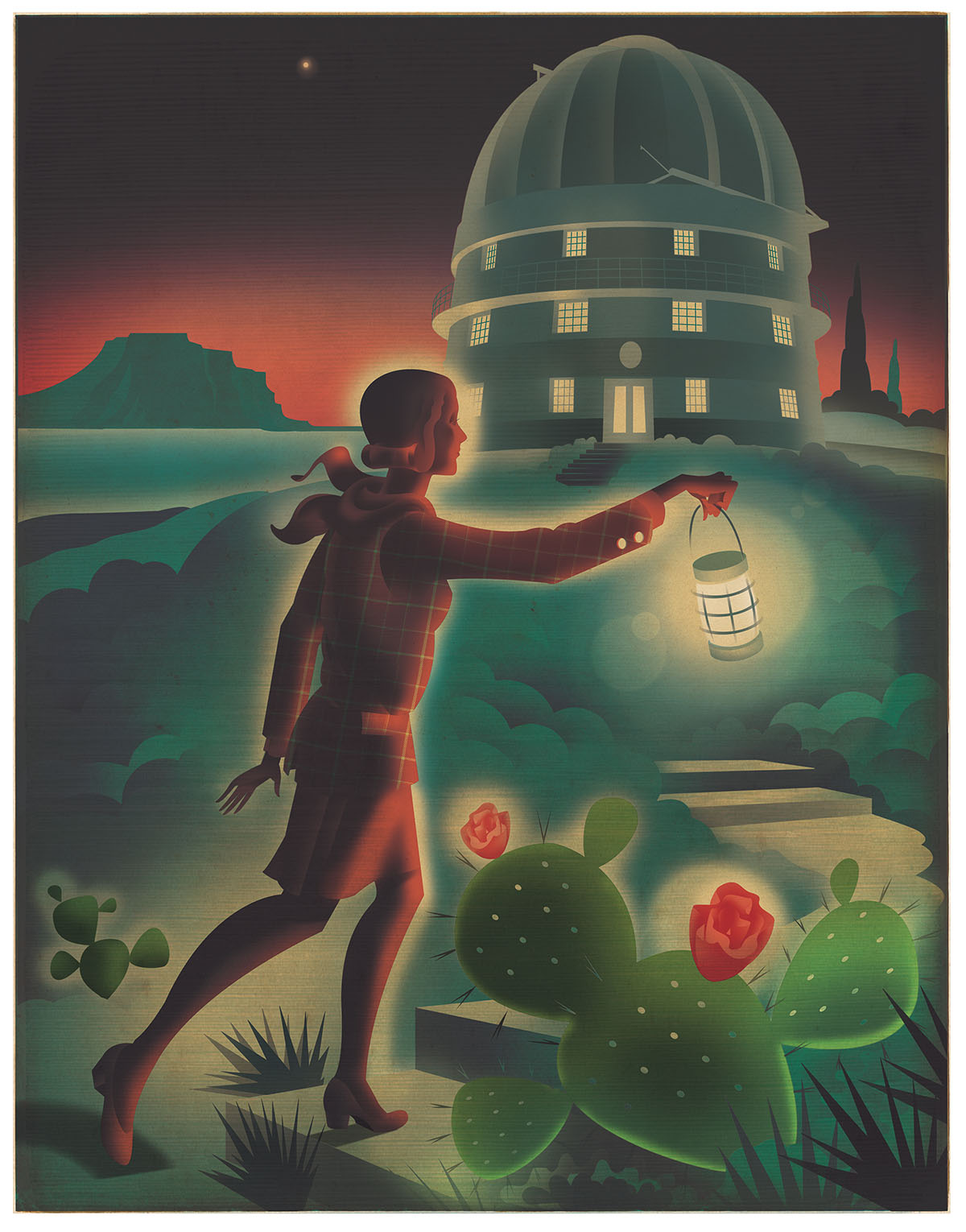

I picture her then, small and stubborn, climbing the stairs that lead to the telescope, in a dress and sturdy shoes. I see her by herself, though that’s probably inaccurate. Before my trip, I corresponded with a retired astronomer named Wayne Osborn, who was deeply versed in McDonald and Yerkes history. At the time, he told me, a woman likely wouldn’t have been allowed to use the telescope unless she was accompanied by a man.

On the drive out west, I’d been listening to a book called Figuring, a fascinating smorgasbord of intellectual history by Maria Popova, one part of which tells the story of the 19th-century astronomer Maria Mitchell. Reflecting on Mitchell’s life, Popova poses a question: What is it we are looking to find in the biographies of pioneering women scientists? “We hunger for straightforward stories of improbable achievement against towering cultural odds,” Popova writes, insinuating that the actual stories are surely more complex.

Was that what I was longing to gain in Farnsworth, some sort of inspirational STEM heroine? I didn’t want to make too much of her having been a woman in a male-dominated field, but then again, had she not been a woman, I wouldn’t have been so intrigued. It was the notion of a woman scientist in 1941, traveling to isolated West Texas, that had hooked me.

The rule requiring a female observer to have a male escort, if it was a rule, is naturally no longer in place. I timed my visit to the observatory to overlap with that of Judit Ries, an astronomer from the University of Texas at Austin who observes newly detected, near-Earth objects—namely asteroids and comets—to identify any that might collide with our planet. Ries grew up in Hungary and came to Texas for her Ph.D., which she completed in 1992. She’s been coming to the observatory since ’97.

We’d arranged to meet at the lodge for visiting astronomers, and when I arrived, at around 6 p.m., I found her in the dining room, a modest space with a grand view of the mountains. She was sitting with three other scientists, all of them women, eating ice cream and nursing cups of coffee. In fact, but for one older man and a male student of Ries’, both seated elsewhere, they were the only people present, as though observing the night sky were primarily a job for women.

None of them had heard of Farnsworth. After I explained who she was, the conversation turned to notable female astronomers of the 20th century, like Cecilia Payne-Gaposchkin, who came to McDonald’s dedication ceremony in 1939, the lone woman in a group of more than 30 eminent scientists present for the occasion. (Fourteen years earlier, Payne-Gaposchkin had demonstrated that stars were composed mostly of hydrogen and helium, in what Struve called “undoubtedly the most brilliant Ph.D. thesis ever written in astronomy.”)

Another was Beatrice Tinsley, who was born in England, grew up in New Zealand, then married an American and moved with him to Dallas in the 1960s. Commuting to Austin from there, she became the first woman to receive a doctorate in astronomy from the University of Texas. Tinsley made crucial discoveries about galaxy evolution but couldn’t find a permanent job in Texas. “So she went to Yale because she got the chance for a career,” said one of the women, an astronomer from Arizona named Lisa Prato. “She left her husband, and she left her children.”

“It was a rocky marriage, from what I understand,” said Anita Cochran, an astronomer and the observatory’s assistant director.

“She gets a lot of grief for that—how can a woman leave her children?” Prato said. “But men do it all the time. I always think how ripping that must have been”—to have been forced to choose between pursuing her career and raising her kids, that is. Prato had once heard another astronomer speculate that after moving to Connecticut and divorcing her husband, Tinsley might’ve had a romantic relationship with a fellow scientist.

“I don’t know,” Prato said, “but if it’s true it would make me happy that—”

“That she found love,” said Cynthia Froning, a researcher from the University of Texas.

I couldn’t help but notice how—for lack of a better word—feminine this conversation had turned, a group of women speculating about the love life of another woman. Yet that seemed right—you couldn’t fully tell Tinsley’s story if all you talked about was galaxy evolution. If she did find love, it didn’t last for very long, the astronomers noted: Tinsley died at the age of 40, from cancer.

The next day, in the gift shop of the observatory’s visitors center, I would find Tinsley in a coloring book devoted to women astronomers, part of a “Women in Science” series. Lately it’s become a cottage industry: stories of women scientists, packaged to encourage girls to follow in their footsteps. There’s something about this that needles, that makes me want to counter with coloring books showing men in historically female-dominated fields. “Men in Elementary Education,” maybe. But at the same time, I do actually like the women-of-astronomy coloring book, and I buy it for my 5-year-old daughter.

When Farnsworth began her sabbatical trip, she was almost exactly the age I was during my trip last fall, a few months shy of 47. It’s not exactly uncommon, at the age of almost-47, for intellectual questions to take a back seat to practical concerns, to taking care of business and taking care of other people, so that at times I’ve wondered whether the spark of curiosity is something that eventually dwindles, like neglected muscles. “I don’t think I get excited about things the way I did when I was young,” an older acquaintance said to me recently. My instinct was to reject the notion of her fading excitement—But what about traveling to new places? Learning new things?—even as I feared that it might be inevitable.

It’s not uncommon, at the age of almost-47, for intellectual questions to take a back seat to practical concerns, so that at times I’ve wondered whether curiosity is something that eventually dwindles.

“Where does it live,” Popova asks in Figuring, “that place of permission that lets a person chart a new terrain of possibility?” In 1940, as Farnsworth prepared for her sabbatical, she corresponded with Struve to fine-tune her plans. Her intent was to borrow from the McDonald Observatory a portable spectrograph—an instrument that separates light into a spectrum of component wavelengths—and take it to the Southern Hemisphere. She would use it to observe an eclipse and later to take spectra from the emissions of the night sky—that is, radiation emitted by atoms in the atmosphere. That data could then be compared to night-sky measurements taken in Texas.

She looked into the option of traveling to South Africa, yet in response to her inquiries, a British astronomer supervising an observatory there sent a discouraging reply. He couldn’t offer her accommodations, he said. While there were suitable boardinghouses in a nearby town, “that is 5 miles away by road and living there would mean driving up a hill by car. This after dark is not really safe for a woman by herself, unless she carries a revolver and is prepared to use it . . .”

Whether this was sound advice or prejudiced fearmongering, Farnsworth had to look elsewhere. “I shall not resort to firearms,” she wrote in a letter to Struve, nor would she carry out any plan without the approval of her local hosts.

Instead she set her sights on South America, and she sailed out of New York that August. In Brazil, where she went first, clouds prevented her from observing the eclipse as she’d planned. Ultimately, though, the expedition was a thrilling one, as she would later describe in an essay for the magazine Popular Astronomy.

“All my life I have wanted to sail south, to see the hidden glories of the southern skies and the changing aspects of the celestial sphere,” Farnsworth began her article. She spent the bulk of her trip in the mountains outside the Argentine city of Cordoba, at an observing station known as Bosque Alegre. There, she set up the spectrograph inside the telescope dome and spent her nights observing.

“For exactly two months, from October 31 to December 31, this richness was mine,” Farnsworth wrote. The exuberance of her report is infectious. On her trip, I imagine, she had a chance to rekindle the passions that had led her to astronomy in the first place—in a spot called Bosque Alegre (“happy forest”) no less!

The fact that afterward she traveled to West Texas in person, rather than shipping the spectrograph back, suggests she went there to make more observations, likely in order to compare them to the ones made in South America. I never turned up any documentation of that, but I did receive a follow-up email from Osborn, the retired astronomer. After our initial correspondence, he managed to gain entry to what he called “the Yerkes vault,” and unearthed some of the night-sky spectra Farnsworth took in Argentina. A photo he sent me shows tiny circles of film, no larger than dimes, cased in plastic and marked “Bosque Alegre.”

All of us, especially as we grow older, could probably use a sabbatical in the happy forest—or at least a three-day trip to West Texas, where time registers differently than it does in a city, and various inflated anxieties start to shrink back down to size. Without trying to, I breathe more deeply there. It seems automatic, as though there were some bodily drive to inhale a view.

At the time of my visit last fall, Ries was using the Struve telescope to make observations, and at dusk I followed her and an undergraduate, Abdullah Assaf, into the building. During the early days of the observatory, before the construction of the astronomers’ lodge, visitors would stay in the telescope building, where the lower level is decorated with art deco flourishes—glass-front bookcases, a tiled floor with an inlay of the zodiac. The telescope, too, presents as a period piece—a steel behemoth. “It’s an old lady, so it has quirks,” Ries said, as she began to prepare for the night ahead.

While the sun was setting, we ventured onto a catwalk. Crepuscular rays streaked across the sky, and Venus, Jupiter, and later Saturn gleamed above the mountains. Over at the neighboring Harlan Smith telescope, where Prato was beginning her own work, the dome was slowly opening.

Back in the control room, seated before a bank of computers, Ries and Assaf chose an observing target, and we could hear the creak and rumble of the dome as it slowly rotated into position. Trying to locate a possible comet, they aimed the telescope toward its predicted position, took a series of exposures, and confirmed it was indeed there, moving against the starry background. Afterward there was a lull. Assaf checked the score of a Houston Rockets game. It was dark and quiet, their faces glazed by the light of the screens. They went on to the next object and repeated the process. So it would go, until dawn.

I tend to idealize scientists, precisely because I think of them as having ready access to happy forests, to something outside themselves that has compelled them since they were young. And if reality is not always that way, even for scientists, I’m still drawn to their work because of the way it takes me outside myself and illuminates some corner of nature.

“Seeing,” in astronomy, is a quality that can be better or worse. Even when a telescope is focused, the sharpness of an image varies according to the amount of turbulence in the atmosphere—when we perceive stars as twinkling, that’s because of turbulence. The flicker that the casual stargazer might admire represents worse seeing, a loss of accuracy for scientists. Maybe there is something analogous, if not so easily measured, about the way I look at the past. Maybe history’s female astronomers are, for me, twinkling objects.

I can’t bring Alice Farnsworth sharply into focus, but I can place her at Bosque Alegre or at the McDonald Observatory, and that moves me, her admirer 80 years later. What I came back home with, after my trip, was something like a silhouette on a tiny circle of film, which if you were able to enlarge it, might show a woman, a short, skirted, nocturnal creature who’d been traversing the Americas with a portable spectrograph, now back at the McDonald Observatory, in the foyer beneath the telescope. I can just about hear her heels clicking on the tiled floor as she prepares to climb the stairs and spend another night up in the dome, measuring emissions from the sky.